Tell us about your career path from New Delhi to New York? Any advice for prospective Parsons ADHT students planning a move to the United States?

Before coming to Parsons, I was working in New Delhi as a journalist, writing for the weekend edition of a paper. I would write stories about people who were doing something new, making something interesting—maybe a beautiful chair, a bicycle of bamboo, setting up a whacky new office, a new clothing line of banana fiber and silk, and such. I never really called it design with a capital D. I had a cozy apartment and good friends. My family was in a city just a few hours away. I was settled and comfortable. There had been a breakup with a boyfriend, and that possibly had something to do with staying up late nights reading random blogs. That’s when I came across Susan Yelavich’s note on the MA Design Studies blog. I instantly knew I had to pursue it. I had to at least try.

However, I belong to that group of people who don’t believe that everything is pure coincidence. One thing leads to another, often over time and so subtly, and you connect the dots only much later. Anyway, I had been to New York a couple of years before I moved there for school. I had walked past The New School, down Fifth Avenue, and sat outside Bobst and watched the world go by. I had walked enough of the city as a tourist to know that if you walk slowly, you’re going to get grumpy looks. I didn’t mind it. I smiled back. And when I moved here, I walked faster myself. There was always somewhere to get to.

So I applied to Parsons—shot an arrow into the dark. After being accepted, I bought a one-way ticket from New Delhi to New York. I packed up my apartment, gave away most of my things, except those that could fit into two suitcases.

As much as my career path was about learning design, and about living in a new city—and exploring the world in general—it was ultimately about self discovery. To go from one city to another, from a job back to school, from a place of familiarity to the complete unknown—all of it is related to getting to know yourself better. To potential students of The New School, or any other school which is far from all that is known to them, I’d say, take a plunge. Do it. You’ll find out who you are.

Do you think of yourself as a New Yorker? If so, what are the terms? And did this identity form before or after graduating?

While I lived in New York I definitely felt a sense of belonging in the first few months. New York not only accepts you for who you are, it also embraces you and sucks you in and celebrates you for all your differences or unexpected similarities. No doubt it can be rough—and maybe I’ve been lucky—but I found friends who smiled a smile of knowing and understanding, who disarmed me with their honesty, who sat at the bar and talked of weird, dark politics of the world and made me feel right at home. Also, strangers. If it’s too much to say that most New Yorkers are friendly, it’s safe to say that they are straightforward and will do what they can to help you. When I was moving into an apartment, I found a bed to buy off of Craigslist. The owner—a slightly grouchy German gentleman—was shocked that I didn’t have any tools (to fix up the bed). “Not even a screwdriver?” he had asked, as if traumatized. I apologetically said I would buy one on my way home. While leaving, he gave me his pocket folding tool set. He said that it was old, that he had used it for a very long time—mostly on his bicycle. He said he wanted me to have it.

Hypothetically speaking, where does one in your field live and thrive outside of New York City?

While attending The New School, I learned a lot inside and outside the classroom. Needless to say, the city and its people are a tremendous influence. The city becomes a classroom. Other students come from worlds of their own and bring perspectives you don’t ordinarily consider. To be honest, I tried desperately to stay in New York after graduating from the program, to work for a couple of years simply because there is so much happening and there’s so much scope. But visa issues didn’t make it easy.

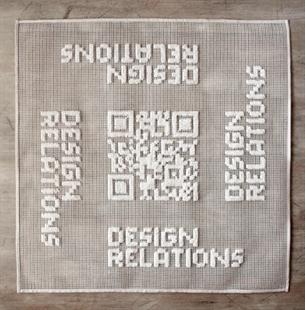

Returning home had its share of excitement. India has its own set of possibilities. Design is a field that’s everywhere and beyond borders and across cultures. The Parsons Design Studies Program gives you a very open-ended socio-political perspective of design. So even if I took electives as specific as Dutch Design or History of Modern Architecture or Socially Engaged Art Practices, it all essentially gave me an anchor to grasp what is going on in the world. Some people might prefer to learn specifics, to focus, to specialize—and you can do that. But for me, as a journalist, I was seeking coordinates, milestones, directions to navigate the world with a little more knowledge and understanding. When taking up an issue to write about, I want to come from a sensitive place of understanding. Which is also why I don’t find it imperative to be in one particular place or market hotspot suited to my field of work. An IDEO at San Francisco or Museum of Art+Design in New York would be amazing, but a weaver’s studio in rural Nepal that is collaborating with designers to contemporize their weaving traditions is equally fantastic to me. The world is my oyster.

How has life been post MA DS? How do you think the courses have changed your course?

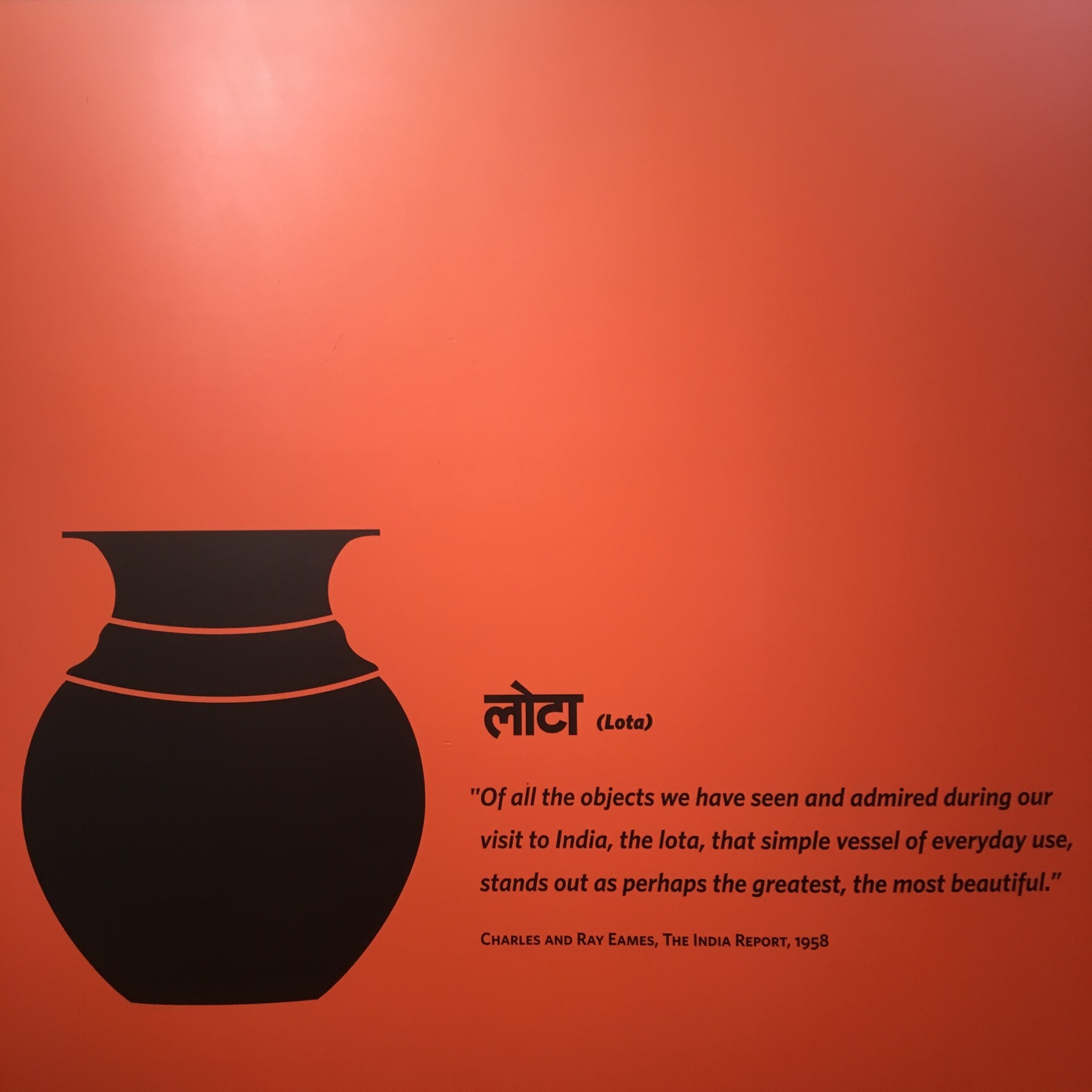

I am back in India now. My central area of study during the program (including my thesis) and after the program has been about the relationship of craft and design. In India, you grow up in a significantly handmade culture. And yet it’s equally industrialized. So the lived experience of craft is very alive and thriving, rather than just a theory that existed pre-industrial revolution. It’s not a complete surprise to me that my research and interest lie in craft and design. Since my return, I have been traveling across India—Pondicherry, Cochin, Kutch, Kashmir—to centers of traditional crafts, to craft+design collaborative studios, to artisan workshops, to design schools. I’ve been doing this with the aim of putting together a travelogue of the craft and design landscape of India.

While I am from India and have lived here all my life, I don’t think I’ve considered and traveled through its length and breadth before, as I’m doing now. And it is certainly my period of study at The New School that has brought this on. Sometimes one has to detach and go away from the familiar, to look at it from a distance and return with a renewed perception and vigor. And it helps tremendously that while you’re away, you’re among a set of people who put you through painful projects of research and writing.

Next week I’ll be starting a new job: a writer at a newspaper, covering design and culture issues. I’ll be based in Mumbai, which is similar to New York—a fantastical, messy, churning pot. While I write short weekly stories, I hope I will be disciplined enough to continue working on my book and not lose the steam that MA DS and New York has built for me.

Do you think your writing, or your work in general, has changed after graduating from The New School? In terms of voice, insight, theory, and other writing skills, have you compared them with your journalism before Parsons ADHT?

Developing writing skills is a constant, persistent, unending process. And design knowledge evolves and expands as each day passes. While I admit and submit to that, I find that a graduate course really gives you an edge. It gives you the tools to hammer, chisel, crack open something with a little more sharpness and precision. It equips you with a way of thinking and approaching issues.

Having said that, I find that when I write an article and read it a few months down the line, more often than not I’ll be cringing at what I’ve done! But that’s just me and the ghosts I have to battle on my own. And it doesn’t stop me from writing at all. During school’s second semester, I interned at Metropolis Magazine, where I had the opportunity to write. The year after, I interned at Maharam, a textile design studio, doing writing work that was specific to the textile industry. Soon after school, I worked at Herman Miller’s editorial department, writing about their historical, as well as new, products. I think there’s something that has changed, though. I don’t find myself writing for the sake of filling newspaper space. I need to have an original idea, however small, and then build my language around it. I also think there’s more clarity in my narrative. I’ve realized that the more you know, the more there is to know. And that at some point you will miss out on something quite crucial. Yet an independent idea is invaluable. The authenticity of your voice will carry forth your argument despite its limitations. Which is why I want to reiterate that the most valuable thing about this MA program has been to help me develop a way of thinking. My teachers and peers are to thank for that.

To elaborate a little on your area of interest, how do you interact with a pre-modern idea of craft and a post digital state of design? What has survived from the old infrastructure that you find indispensable or, perhaps, unhelpful?

While in theory craft is pre-modern, to me the notion is timeless. It has existed throughout history, even at the heart of the Industrial Revolution, adapting to become part of the industrial model in one way or another. Whether as a division of labor or a specialization of skill, in small or big ways the notion of craft has existed. But yes, the industrial and digital modes of production change the definition and scope of craft quite significantly from its pre-modern conception. To my mind, it is an interesting moment for craft and its renewed relevance simply because the digital model allows for more freedom in conception and production. It gives the maker power over each individual piece, more than an assembly line industrial model has offered. I also see a u-turn in the values that we aspire to. For example, aesthetics like imperfections, unstandardized pieces, the qualities inherent in the handmade. However, there is a tendency to fetishize such qualities. I believe that craft has to be understood not as a category of handmade objects but as a way of thinking and making. Something that requires skill, work hours, material knowledge, and learning by doing. Craft has the capacity to intersect philosophy, social practices, technology, sustainability—in turn embedding a humanity into what we make. Most importantly, craft is about people. I was recently reading a book called Critical Craft, and the authors Clare Wilkinson-Weber and Alicia Ory DeNicola brought the discussion of craft down its expansive anthropological reach. “We believe that research on craft and artisanship has the potential to open up new and evocative questions about the ways that we construct some of anthropology’s most critical contemporary concerns: technology, access to markets, means of production, control over work practices, tradition and innovation, urban and rural spaces, human rights and the environment to name just a few,” they wrote. So yes, I think craft as a way of thinking-knowing-making is indispensable. But to look at it through a nostalgic lens of the beautifully handcrafted objects of yesterday—that’s unhelpful.

Read Komal Sharma’s work here.

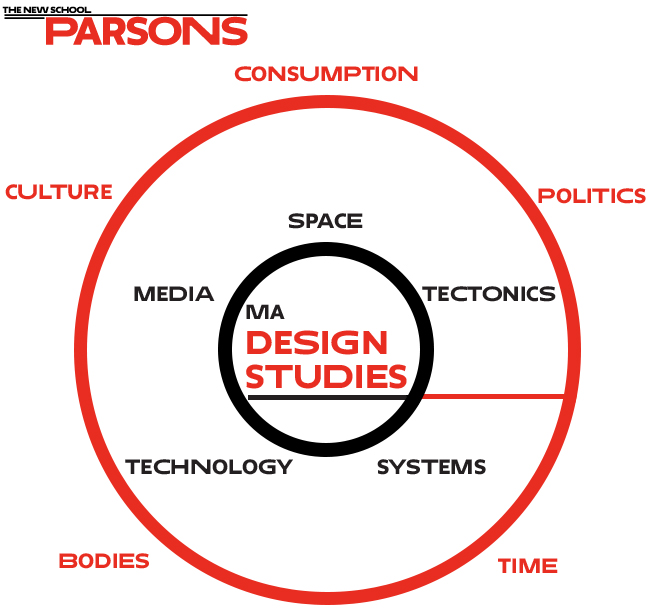

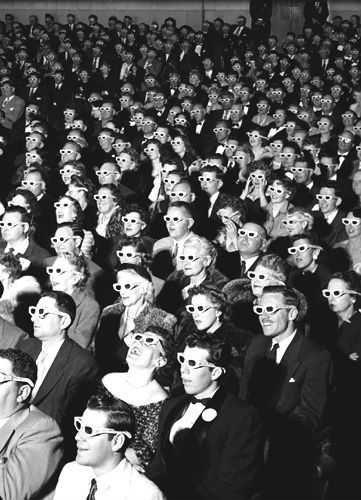

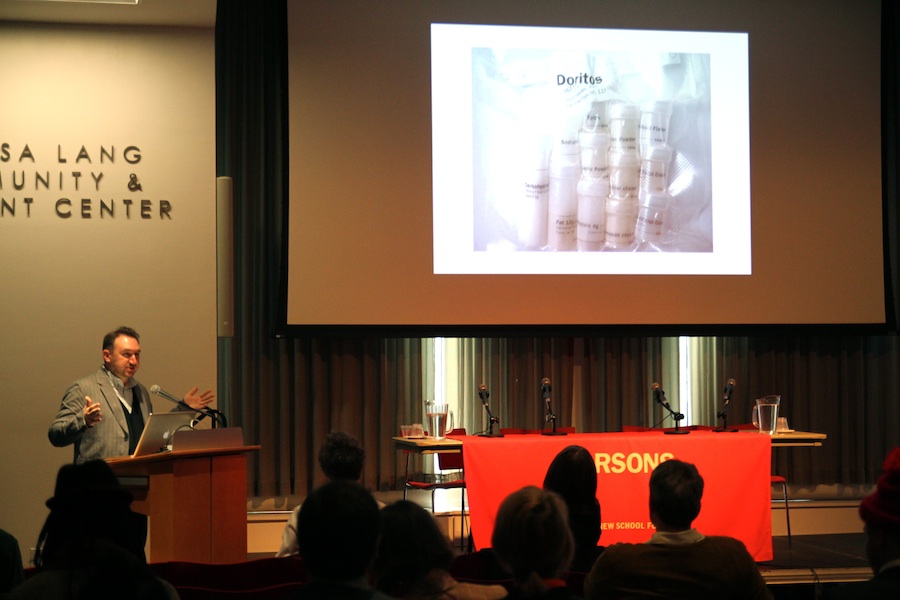

In Design Practices & Paradigms, members of the inaugural MA Design Studies cohort at Parsons explored the scope and ambitions of design in the 21st century. Students interviewed designers and mapped their practices. They wrote about their approaches to production, collaboration, and authorship as well as the social and intellectual context that shape their respective projects and values. Featured

In Design Practices & Paradigms, members of the inaugural MA Design Studies cohort at Parsons explored the scope and ambitions of design in the 21st century. Students interviewed designers and mapped their practices. They wrote about their approaches to production, collaboration, and authorship as well as the social and intellectual context that shape their respective projects and values. Featured

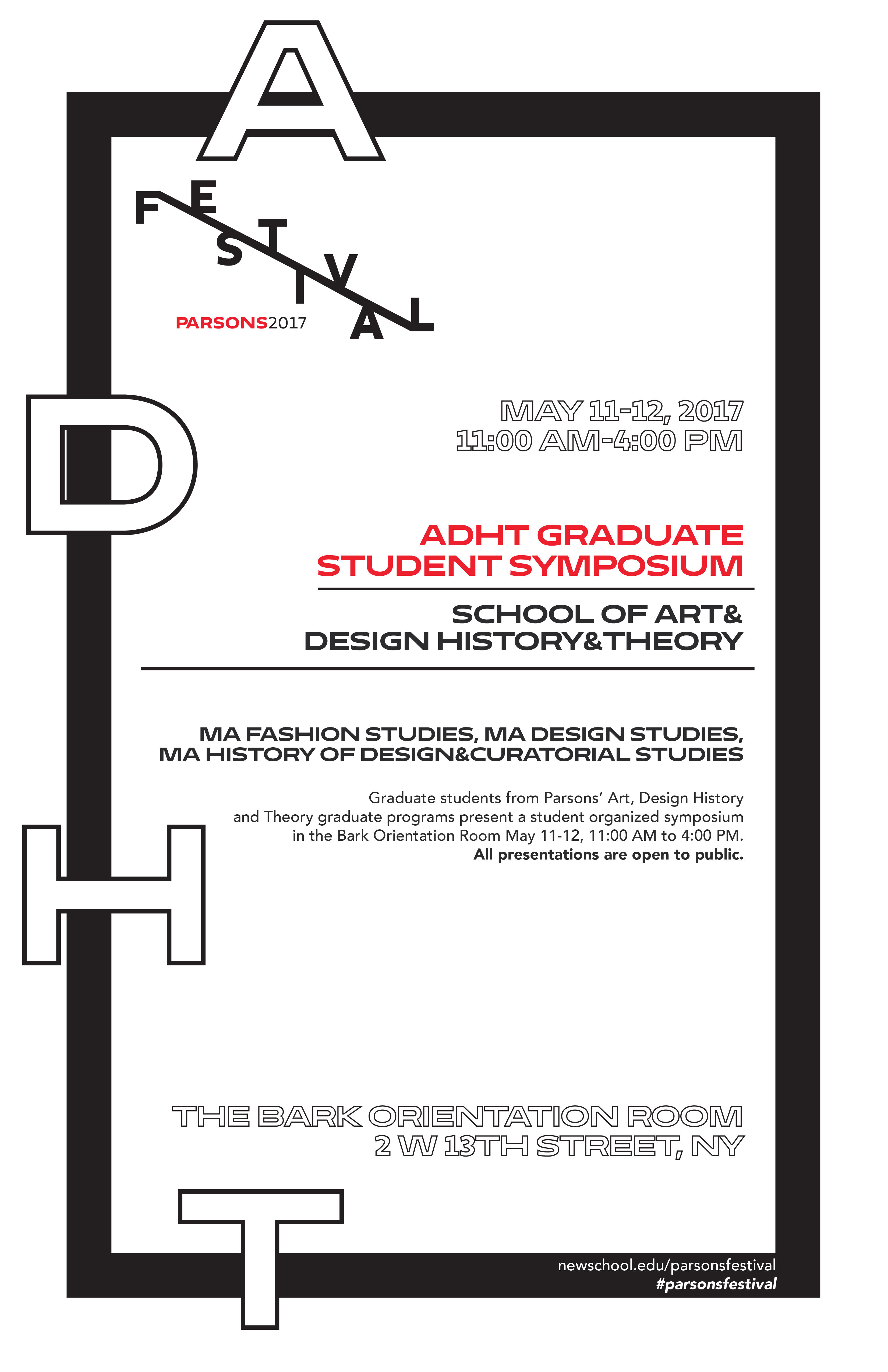

Our inaugural symposium,

Our inaugural symposium,

NORDES, Norway, Design (and not in that order)

By Susan Yelavich

Oslo side street. Photo: Susan Yelavich

Oslo looks to be a very different kind of city, even for a reasonably well-traveled New Yorker. It seems largely residential populated by six to eight-story buildings (many in a restrained, neoclassical style others in Scandinavian cottage form) in pinks, blues, yellows, reds, and white, framed with trees and parks of the deepest green.

Construction around the harbor in Oslo. Photos: Susan Yelavich

Yes, there is all the new construction on the harbor, which speaks to a more rapacious Norwegian prosperity. But otherwise filthy lucre is hardly in evidence. You don’t see it in people’s dress, which tends toward practical sport-driven garb. There is almost no aggressive advertising outdoors and little in the way of attention-getting shop displays. All in all, a feeling of self-effacement dominates, which makes for an odd kind of assertiveness.

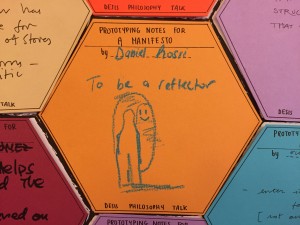

Equally, the NORDES 2107 conference was marked by calls for modesty. They were evident in almost all of the keynote speeches. Yoko Akama spoke of “philosophies of absence [that] take non-being or nothingness as the necessary grounds for being” as relevant to truly conscientious design. Even Westfang took exception to ‘design exceptionalism.’ Thomas Binder embraced the idea of design’s ‘weakness.’ All this at a conference of designers dedicated to participatory design, co-design, and social change. (Even in the workshop I co-led with Nik Baerton, Virginia Tassinari, and Elisa Bertolotti, participants cited their solitary acts of writing as the most satisfying part of the collective storytelling process.)

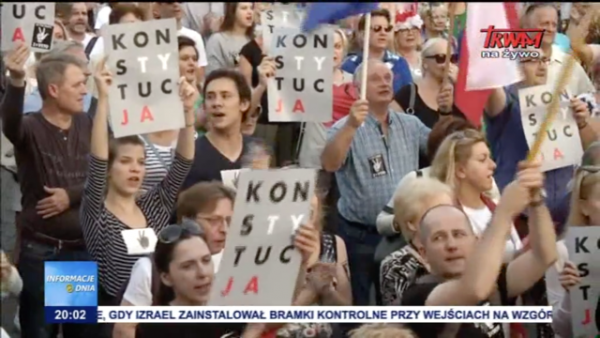

However, none of this amounted to calls to return to the Post Modern 1980s when architecture and design withdrew from the social sphere after modernism’s failure to ‘change to world.’ It was rather a recognition that the ambition to ‘change the world’ is ridiculously hubristic if seen as a project of design alone. Well-intentioned design efforts to care for refugees or house the homeless can be tacitly complicit with the political conditions that make them possible. Mahmoud Keshavarz and Jocelyn Bailey, respectively, made the case that designers are often put in the untenable position of perpetuating greater political systems of injustice in their efforts to help. For example, in providing shelters for those the state refuses to care for, designers risk confirming the state’s estimation that these are people unworthy of the resources we ourselves take for granted. In that view, refugee housing could be considered second-class shelters for second-class citizens.

Notably, though, there was a scarcity of propositions as to how to contend with design’s relative powerlessness in this difficult present when democracy and other forms of political agency are under threat. If retreat isn’t ethically tenable, then what is? Here Evan Westfang (whose own work has to do with making public data both public and visceral) offered an interesting response. He called for a return to ‘normative design’ – not design-for-design’s sake, the stuff of international design fairs and the like. The ‘norm’ of design that he referred to is it’s inherent generosity.

Oslo Opera House, Snøhetta, Wikipedia.

That said, I’m not sure he or anyone else in Oslo would find that generosity where I did during my brief visit, given how skeptical we’ve become of design that is anointed ‘successful.’ I’m referring to my experience of Snøhetta’s Oslo Opera House (2008), which yielded so many unexpected epiphanies—epiphanies, which I suspect are not mine alone. Walking up, on, across, and down its sloping planes, you are never quite sure whether your feet are on the ground or in the air.

Oslo Opera House roof, Snøhetta, Photo: Susan Yelavich

Childhood and adult sensations were felt more than remembered. For me, at least, there was a palpable sensation of the risk that comes from playing in and on a space that seems illicit, namely, the roof. There was the pleasurable disorientation of losing any sense of scale while walking on a glaring white landscape akin to a desert; and the mysterious possibilities of hide and seek around its volumes that Michelangelo Antonioni captured on the roof of Antonio Gaudi’s Casa Mila (1912) in his 1975 film “The Passenger.”

Jack Nicholson on the roof of Gaudi’s Casa Mila. Still image from the 1975 film “The Passenger.”

My conscience pricks me as I write this paean to the pleasures of feeling, to paraphrase Philip Johnson, my ‘molecules being rearranged’ by architecture. Yet, is this so selfish? The philosopher Jacques Rancière argues otherwise. He places value on “the possibility of being together and apart” because space for solitude has become “a dimension of social life which is precisely made impossible by the ordinary life… .”1 (Ordinary life, here, being the relentless bids for our money and our attention.)

Now Rancière is actually writing about the conditions in Paris’s poor suburbs where he sees a need for spaces and places that offer the dignity of solitude (not the despair of loneliness) for its residents, the very same people who designers are quick to gather into configurations of participatory design. But I would argue both situations – the collaborative and the solitary – are powerful frameworks for design and, that at its best, design creates conditions to be ‘together and apart.’ Even and especially on the roof of an Opera House, where seeing an opera isn’t required.

“Apart and Together on the Oslo Opera House roof.” Photo: Susan Yelavich

Aesthetic Regime of Art” taken from an edited transcript of a plenary lecture delivered on 20 June 2006 to the symposium, Aesthetics and Politics: With and Around Jacques Rancière co-organised by Sophie Berrebi and Marie-Aude Baronian at the University of Amsterdam on 20-21 June 2006. http://www.artandresearch.org.uk/v2n1/ranciere.html Accessed 6/20/17.