Over the weekend, I found myself in a small biohacker space in Brooklyn. Seemingly a far cry from my usual wanderings at museums or Parsons’ Making Center, it felt fitting to be taking a sample of my own DNA to learn the protocol for a space I hope to find myself in more often.

Making a Home For Graphic Design Education in the Liberal Arts

As a BFA graduate of Parsons and a practicing graphic designer, I find myself currently exploring the political, philosophical and critical thinking related to design now more than ever as I return to my alma mater for my master’s in Design Studies. Hoping to gain insight into the current realities of design educators, I decided to make the most of my renewed AIGA student membership privileges to attend the “Graphic Arts in the Liberal Arts” panel discussion on November 12, 2016. The discussion was moderated by Liz Deluna, associate professor of design at St. John’s University, and Mark Zurolo, associate professor of design at the University of Connecticut. I was particularly intrigued to hear how far they would take their guests on the topic of teaching graphic arts in the liberal arts. The following is a condensed and edited summary of what I observed. For the full take, see AIGA’s blog post.

The Deep “Why” of the 2016 Election Tragedy

by Susan Yelavich

By sheer coincidence, my students and I read Clive Dilnot’s 2012 essay “Chris Killip: The Last Photographer of the Working Class”1 on our blackest Tuesday: Election Day, November 8th. (We were originally meant to discuss it a week earlier.) Either way, back in August when I was refining the syllabus, it didn’t cross my mind how acutely relevant his discussion of Killip’s photographs would prove.

Ten Proposals for Tenuous Times

Director and Associate Professor Susan Yelavich participates in the 20th annual HighGround colloquium. Read about her proposals for design and her reflections here:

This year at the 20th annual HighGround colloquium organized by designers Katherine and Michael McCoy at their studio/home in Colorado, I proposed a series of design moves (some strategic, some tactical) to shift social perceptions of people who have been alienated, mistreated, or ignored because of race, gender, immigration, or mental health issues—or any combination of the above that leads to ‘othering.’ (more…)

Clive Dilnot on Remembering John Heskett

Professor Clive Dilnot of MA Design Studies blogs about his friend, the design historian John Heskett, and assesses Heskett’s contribution to the field of design history. Read the full post here on the Bloomsbury Visual Arts blog.

Do Drones Have DNA?

by Jilly Traganou

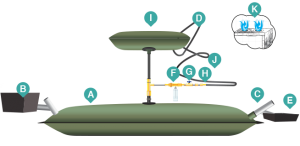

Drone flying in “Research and Methods” class presentation by Mehdi Salehi. Photograph by Mathew Mathews.

“Of course, all the students want to see the big drone flying. A loud, unpleasant noise fills the room immediately. The black and white aircraft floats stably in the air and creates a strong draft in the room, which is apt to produce goosebumps. I am impressed by how insecure I felt. Of course, this drone was not equipped with weapons or other harmful objects. However, the propeller and its speed give me a queasy feeling. No one in the room wants to get too close to it or even feel the propeller near his or her skin. The drone moves around the room like a foreign body, almost like a dangerous animal whose intentions are uncertain and difficult to read, but always ready to attack.” (Lisa Merk, MA Design Studies student )

Misha Volf’s Speech at Graduation Ceremony of MA DS 2016 class

Talk by Misha Volf as the student speaker given at the graduation of MA Design Studies, May 19th 2016:

Thank you, Faculty, Administration, Friends, Family, Graduates,

Two years ago, when I was considering Design Studies, I came in to interview with Susan [Yelavich, Director of the Program]. Among the ways she framed the program, one of them was as a NEXUS of THEORY and PRACTICE. After the interview, as I travelled back home, I was abuzz. “This is perfect,” I thought. This wasn’t going to just be some heady, theorizing about commodities, or semiotics, or the anthropocene; nor was this simply going to be about the production of stuff, putting design to work, so to speak, or something my father with increased longing would call “marketable skills.” No, no. This was going to be something else. This was going to be, … THE NEXUS!

Clive Dilnot’s Speech at Graduation Ceremony of MA Design Studies 2016 class

Clive Dilnot: Introductory talk given at the graduation of MA Design Studies, May 19th 2016:

It is an honor today to introduce to you the 3rd cohort of graduates of MA Design Studies, a very special and indeed brave, group of students.

They are special because the MA in Design Studies is one of the most exclusive degrees in the world. The program is unique in North America and I think is unique in the world. These are, in the best sense of the word a rare group of students. We have to hope they are not also an endangered species.

Breathing Design: A Reflection on the Beginning of the Semester

by Jilly Traganou, Director of MA Design Studies

Design is what we breath here at Parsons; design, that is as much in the process of “cleaning and reorganizing a desk drawer” (Victor Papanek), as it is in the makings of synthetic biology and 3D food printing. Now that the academic year is upon us, I’d like to reflect on everything that we’ve so far accomplished.

This year, students with backgrounds as variable as their places of origin (India, Germany, Egypt, Canada, US, China, Great Britain) have joined Design Studies in continuing the tradition of diversity that has characterized the program since its inception three years ago. Our new students bring experiences and knowledge from the fields of philosophy, art history, media, marketing and, of course, design practice. They are here to engage critically with design, as both intellectuals and practitioners, to bridge theory with practice, to develop their own distinct pathways through elective course choices across The New School and to undertake their capstone work in the second year of study. Our incoming students’ orientation took place in the third week of August. As an initiation to the discourses in which students will be enmeshed in the next two years, we visited two different sites of design, the Navy Yards and the Cooper Hewitt museum: the first, a site of design production, where future designed worlds are being conceived and manufactured; the second a site of display, education and curation.

In the first, we were guided by architects Christian Huber and Vivian Kuan, both associated with the studio Terreform ONE (Open Network Ecology). Christian and Vivian took us on a tour at the modular homes construction company Capsys, a realization of the metabolists’ and other utopian architects’ dream, where homes are constructed in a factory setting indoors to be transported and plugged in or assembled on location. We also visited the Terreform ONE’s own studio where biology meets urbanism in fascinating experimental work such as the Urban Farm Pod, that integrates ideas of urban agriculture with the growing of architecture as food.

The second stop during orientation was the Cooper Hewitt, a site of display, education and curation. Here, we were guided by History of Design and Curatorial Studies student Sakura Nomiyama, who discussed with us selected exhibits of the “How Posters Work” exhibition, while pointing out innovations in the early 20th century mansion of the Carnegie family that houses the museum (its elevator, air-condition, and heating system), which is easy to take for granted a century later. This house was as much a masterpiece of engineering innovation back then, as the Urban Farm Pod is of urban agricultural innovation today.

“Japanese Design Today,” Q & A session, Kashiwagi Hiroshi, Nakamura Yoshifumi, Jilly Traganou (right to left). Co-organized by The Japan Foundation, New York; MA in Design Studies; MFA in Industrial Design, Parsons New School of Design, at The New School, September 2015.

On September 8, in collaboration with the Japan Foundation, New York and the new Parsons MFA program in Industrial Design we hosted the event Japanese Design Today: Unique, Evolving, Borderless. The event included two lectures, the first by Kashiwagi Hiroshi, a prominent design historian of Japanese design and professor at Musashino Art University, and the second by architect and furniture designer Nakamura Yoshifumi, a professor at Nihon University. In his lecture Professor Kashiwagi examined the characteristics of contemporary Japanese design (craft, minimal, thoughtful, compact, cute), while Professor Nakamura’s lecture focused on his architecture of hut dwellings, residences of energy efficiency and minimum size that function as retreats for everyday life. After the lectures I was moderator of a conversation on the state of Japanese design today, which opened up questions on nationalism and otherness in today’s Japan, as well as of the role of materialism in everyday life. Having been a Japan Foundation fellow in the past, and admittedly a Japanophile, I hope that the event has inspired our students to look into future research and funding opportunities offered by the Japan Foundation and other sources, which would allow them to research the role of design and material culture in Japan. We also hope that we will continue our collaboration with the Japan Foundation, who has already co-organized and supported several events with Parsons, such as for instance the Kon Wajiro exhibition on design ethnography in March 2014.

Continuing a guest-Professor sequel that began with Peter Hall earlier this year, in September 14-25, we hosted Albena Yaneva as Visiting Professor at Parsons. Albena Yaneva, a Latourian anthropologist, is Professor in Architectural Theory at the University of Manchester. Albena taught an intensive elective class titled “Ecologies of Practice: An Anthropological Approach to Design” that attracted students from across the New School. She also met individually with PhD students in anthropology, and gave two lectures, one in the anthropology lecture series and one in my Advanced Thesis Preparation class for the MA program Theories of Urban Practice program. Her lectures focused on the concept of cosmopolitical design—the subject of her forthcoming book with Ashgate, an approach to design that takes into account both the material and the living world, and entities with differing ontologies: viruses, natural disasters, climate, carbon dioxide, floods, rivers, and so on. Comsopolitical design can be seen as much in the work of contemporary architects grappling with the problem of the sun glaring in the glass facades of their buildings, as in the work of environmentalists who take care of natural ecosystems trying to balance people’s engagements with nature with acts that regulate ecology and allow nature to “recover.” Albena was a valuable resource for our students who had the opportunity to develop in-depth case study research and writing in her class, utilizing ethnography and developing a pragmatist approach to the understanding design and what it does in the world.

On September 25-27, a group of 14 students and myself attended “A Better World by Design,” a conference organized by students of Brown University and RISDI in Providence, Rhode Island. Besides giving us the opportunity for critical conversations on design and its impact in the world, we enjoyed several of the lectures, such as the one by Alexis Lloyd, Creative Director of the R&D Lab of The New York Times, and a Parsons alumni, on the role of computational systems and the way they can become tools for conversation, an issue which resonates with several of our students’ capstone research.

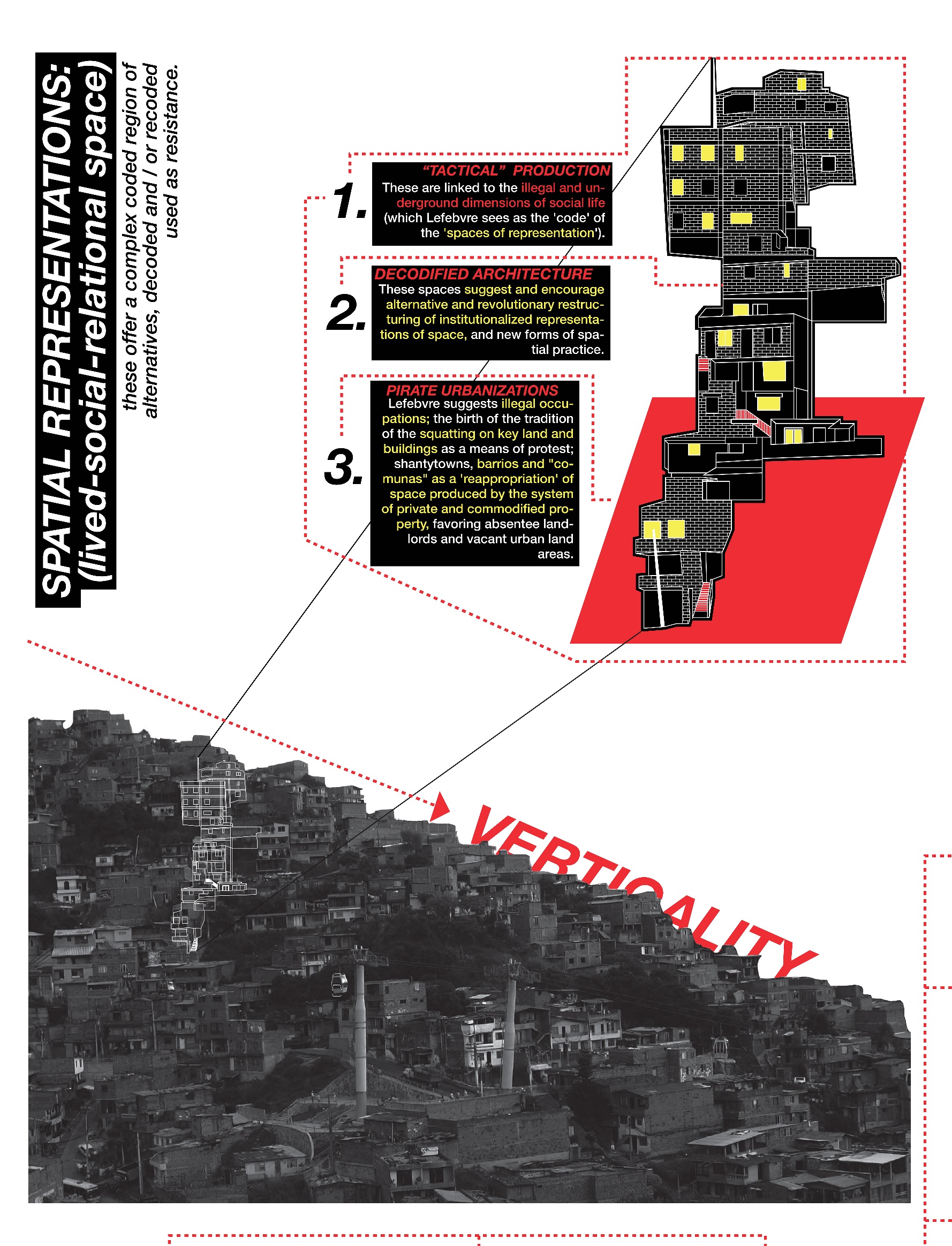

“Spatial Representation: Verticality,” visualization of MA Design Studies student Juan Pablo Pemberty’s thesis titled: “The Spatial Conjunction: Design Redress and the Social Urbanism of Medellin,” submitted May 2015.

On September 30, ADHT participated in the Parsons Career Expo. We were happy to have work of two of our MA Design Studies alumni, Niberca LluberesRinicon and Juan Pablo Pemberty, presented at the ADHT table, as well as the last issue of Design Studies magazine Plot(s).

After the divergence and excitement of the first two months we are now converging our energies into the end of the semester. Many things are up in the ether but I hope it will not be a spoiler if I tell you that our students are Plotting again, and a call for proposals is in the works. We look forward to a productive year!

What Does That Even Mean? Ten Things About “Service Design.”

By Mae Wiskin

Admittedly, I didn’t know what “service design” was a couple months ago (although arguably it has been around my entire life). Until recently service design lacked an agreed upon name or consensus. Service design, most simply, is a hybrid human activity composed of a blending of diverse industries and fields. Given this, there is no simple and clean definition of the term. If you were to ask forty different people what they think service design is and what the future of it might be, you will get forty different responses, albeit with some degree of overlap. As you can probably guess, the main place of overlap is the belief that design ought to be “human-centric.” I would argue, however, that design (in all its forms) has the capacity to be profoundly harmful unless its definition also always incorporates a sense of criticality.

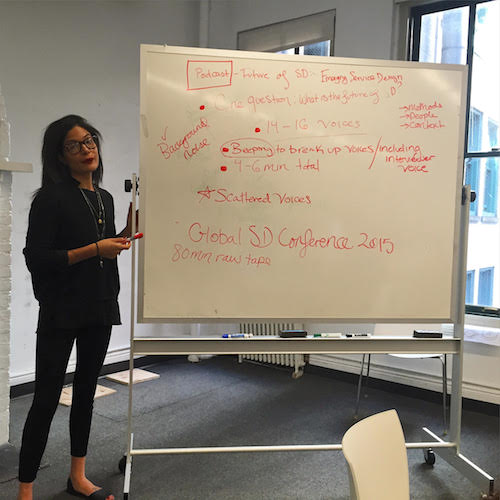

At the recent Global Service Design Conference, held at Parsons The New School for Design, my team and I asked numerous participants what they believed was the future of service design. At the end, we compiled these insightful and often playful perspectives into a simple 6-minute podcast.

What follows is a short list of ten things I learned during the conference.

- Service design is an evolving field that includes professionals from numerous industries and backgrounds, from design ethnographers to CBOs to educators.

- There is no one definition or common language to explain this nascent field. However, the practice of “design thinking” is inextricably linked to the practice.

- Similar to the field of Design Studies, emerging service design is a malleable discourse.

- Service design, at its core, is about both the user and their experience with a designed service; this can be anything from a healthcare service to a cafe blueprint.

- It is an integrative and trans-disciplinary field.

- Service design has given rise to new business models, many of which take the notion of empathy and social design into consideration.

- Service design works to ensure that services are intuitive, desirable, user-friendly, and effective.

- The future of service design is unknown, however, many who have incorporated the practice and its methodologies into their work believe that one day it will dissolve entirely and simply become an assumed part of how people conduct business and also, approach design.

- Service design is an iterative process more than an outcome.

- The primary point of service design is that human behavior, as well as desire, be the precondition for designing any service

Professor Yelavich addresses FAIR Design Conference at Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts

On leave this academic year, Professor Susan Yelavich took time away from her sabbatical project on fiction and design to deliver a lecture on design and leisure this September at the invitation of the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts as part of a conference on design as activity. A summary of her lecture “Product(ive) Leisure” can be found here:

Leisure would seem to be exempt from design’s interventions. The word implies unstructured pleasure from activities chosen and pursued at will; whereas design aims to reconfigure experiences and mediate them through systems, places, and things. Even design that positions itself as a catalyst—like a hiking trail that is more means than end—exerts a measure of control and configuration. Admittedly, there are leisure activities like meditation that are not dependent on things, but even they require space, whether found or purpose-built. So, counterintuitive as it may seem, leisure is not exempt from, but rather open to, design.

The challenge to design, in an age of leisure marketing, leisure destinations, even higher education degrees in leisure, is how to enhance leisure without being overly deterministic. Just as Adorno cautioned that the art of giving gifts is all but lost, we are now in danger of ceding leisure to the industries that produce (and design) environments that script the escape of pressure and the pursuit of pleasure.

Furthermore, with digital technologies that support both work (paid) and leisure (unpaid) within the same devices, we must ask if design should do more to preserve the frisson of contrast between the obligatory and the optional. Alternatively, we might also consider whether life would be richer if the distinction between leisure and work disappeared by virtue of being interwoven by design. In both cases, we must ask who works and who pays for our leisure and whether that work and the economies it supports are exploitive or nourishing.

Understanding the relationship between the scripted and the unscripted, between time as a unit of measure and time as experience, and whose time and labor are entailed in shaping those experiences are prerequisites for designers addressing leisure today. For whether it is pursued socially—community gardening, playing sports—or in individual activities—reading, daydreaming—leisure is incomplete unless it allows for genuine agency and the possibilities of meandering and serendipity. Otherwise, leisure runs the risk of eliciting its nemesis: anxiety.

Transformative urbanism: Cairo’s women-only metro carriages

By Mae Wiskin

Published August 18, 2015

Seven years after the introduction of Women-Only Metro carriages in Cairo, former resident Mae Wiskin explores what this intervention means for the city, public space and gender politics within Cairo and Egypt as a whole.

To many, Egypt’s capital city of Cairo is a maddening metropolis marked by its traffic gridlock, complex religious discourse, and contested gender politics. The metro system is frequently referred to as the only functional and dependable system in the city. It is available for only a single Egyptian pound, and runs fairly frequently. In its current configuration there are two women-only carriages attached to the middle of each train. The cars, which were formally introduced in 2007, enable women to travel more or less unmolested and fluidly around the sprawling metropolis. This makes Cairo one of several cities throughout the world, from Tokyo to Tehran to Mexico City, which have recently implemented similar women-only carriage policies for the purposes of public transit.

What has been the effect of such policies? As a Jewish-American woman of colour and a former resident of Cairo, I became interested in analysing whether gender segregation in the Cairo Metro is simply a matter of protecting women from sexual harassment, or whether it has come to play a role in the larger religious and cultural debate about the role of women in Egyptian society. While I was living in Cairo, I often engaged in lively conversations with Egyptians about these ideas. Later during graduate school, I conducted interviews with Cariene women to give a real voice to this often overlooked quotidian aspect of Egyptian life. Women-only carriages were never going to enter Egyptian society unnoticed and without criticism. Through these conversations and interviews, I realised that the consequences of urbanism (of which the metro is one example) on women’s rights in Cairo extend far beyond its transportation system. The existence of women-only carriages is just one feature of the national conversation about women and their place in public spaces — a paradigm that is still evolving.

The metro was built out of a powerful drive to create a globally-inviting Cairo. Its intentions were to lessen traffic congestion, increase more fluid public access through the city, and facilitate women’s safe passage. The metro is the circuit board of Cairo. It carries around three million people per day and is unarguably the fastest, cheapest and safest means of public transportation in the entire country. It is also one of few metro systems in Africa. Three lines and sixty-one stations connect over forty-eight miles of Cairo. It is a vibrant and veritable system.

Until the women’s-only passenger cars were introduced, however, Cairene women were regularly subjected to gender-based violence, harassment, and unwanted touching on the mixed-gender trains. It is well documented that sexual harassment is a profound problem in Cairo. According to a 2013 UN report, a staggering 99% of women and girls reported having had experienced some form of sexual harassment. Still, Cairo is certainly not unique in its harassment issues. In Japan, for example, it has been reported that over 64% of women in their 20’s and 30’s reported being groped on the train or in transit stations. Indeed, the problem is so well recognised in Japan that there’s even a special name for subway sexual harassment: chikan.

Due to this, in 2000, women-only train carriages first appeared, aimed at protecting women from assault. In Egypt, women-only train carriages were only introduced when the government finally acknowledged its “epidemic” of sexual harassment. The role and make-up of government is a critical sticking point; according to the Global Report of the International Women’s Media Foundation, Egypt has a very low global ranking: 128th in terms of women’s representation in national office. This may in part explain some of the reasons why change in both the transit system and within the country as a whole has been so incremental. After the economic summit in Egypt on March 5th, 2015, the Egyptian Ambassador to the UN, Mervat Tallawy announced a national strategy to combat violence and harassment against women. The government purports that it is also drafting constitutional legislation that will specifically address violence against women in all its forms in the public sphere; the most common of which occurs on public transit. This is a revolutionary step towards helping to address gender-based violence against women in Egyptian society.

The debate over the role of women in Egypt is complex. According to Mona Makram-Ebeid, a former senior member of the Wafd party, “the islamic movement makes the accusation that women are invading public space and should be at home with their children”. She ultimately argues the conservative perspective that the women’s place is not in public life. Women are not to be seen, but should simply exist as quiet spectators. Moreover, many Egyptian males claim that women in the workplace is a primary source of congestion on the public transportation system, while also exacerbating the problem of male unemployment. This is simply one perspective and there are myriad arguments, which counter these assertions.

The Egyptian Gazette, presents both sides of the debate by stating the following: “since women have called for equality with men in all spheres of life, it is natural that she should fight like him for an empty seat”. In theory this proposition is fair; however, in reality, the picture of gender equality is far more complicated than the “fight” over a metro seat. One interviewee, Laila Abdel Hamid, poignantly and frankly frames the debate in this way:

“The presence of women-only carriages opens up an interesting platform for urban discourse about equality in ownership of public space. It’s a double-edged sword in my opinion. On the one hand, it offers women a space to feel comfortable and possibly safer from harassment, but on the other hand, it contributes to the ongoing gender segregation process and acts as a constant reminder that women are different from men.”

These interviews demonstrated how gender segregated public transportation has become a proxy that highlights contested gender dynamics in cosmopolitan Cairo.

There are yet other voices that argue against the women-only carriage policy. The Egyptian Gazette, in speaking about segregation in subway cars wrote, “it pulls us back to the dark ages of segregation and even humiliates our women, treating them as weak and subordinate”. Adding yet another dimension to the debate, journalist Jessica Valenti of The Guardian brings up the critical point of calling on men to take responsibility:

“There’s no doubt the harassment women face in public spaces needs to be addressed…. We’ve been subjected to regular catcalls and groping for far too long. But while the idea of a safe space is compelling, this international trend – which often comes couched in paternalistic rhetoric about “protecting”women – raises questions of just how equal the sexes are if women’s safety relies on us being separated. After all, shouldn’t we be targeting the gropers and harassers? The onus should be on the men to stop harassing women, not on women to escape them.”

These conflicting assertions illustrate the complexity behind the ongoing debate surrounding women-only carriages. Beyond the contentious discourse, the question of who has an actual right to public spaces in Cairo is fundamental to understanding how women-only carriages might serve as a site for transformative urbanism. It is important to note that all public spaces in Cairo are highly gendered. Men maintain a sense of entitlement over the public sphere, which makes it difficult for women to meaningfully break through those barriers in order to access those spaces freely. Given that Egypt is a male-dominated society, women are forced to constantly negotiate with patriarchal systems. In the public realm, women establish respectability and a sense of personal safety via their conservative dress and physical separation from men. Egyptian women are now actively trying to renegotiate the landscape of public space.

Separate from the ongoing discourse, the quotes below from two Egyptian women help illustrate how women actually experience the public sphere, highlighting the significance of the women-only carriages. In the words of resident Laila Abdel Hamid:

“Women in Cairo are exposed to different types of sexual harassment on a daily basis, especially while taking public transportation but also by simply walking around the city. While you’re walking in or out of the metro station, harassment happens too. But if you make it to the women only carriages, you’re relatively ok, because women surround you and if a male intruder is spotted, women riders will group together to expel him.”

When asked about women-only carriages by a BBC correspondent, one middle-class Cairene woman answered by saying, “we should have one or two more carriages. It is not asking too much to breathe, is it?”

There is a growing worldwide trend towards gender segregated public transportation, but it is interesting to note that while women do not have to use women-only carriages, in transit systems such as Cairo’s and Osaka’s in Japan, no legal sanction can be taken against men who enter women-only carriages. In addition, it is important to mention that women-only train carriages are usually located at the very end of the train. This forces women to walk the length of the train in order to access them. What’s even more problematic is that women-only train carriages are not available on all trains and/or at all times of the day. They are usually only provided during rush hours. This raises questions about the efficacy behind integrating such design features if they are not backed with legal force or with an adequate semblance of consistency.

I contend that the design of the Cairo metro not only transfigured the city, but also significantly transformed gender politics within the country. From the interviews I conducted, I got the sense that though women-only trains are appreciated, women still worry that they may only enhance divisions between the sexes and even worse, prevent necessary action to government policies aimed at designing more welcoming, safer and more inclusive public spaces. I would argue that Egyptians are only just beginning to acknowledge their city’s positive transformative urbanism and as such, are still contending and grappling with what its consequences may mean for their society. Debates over gender discrimination and sexual assault are no longer taboo issues in the country. This, in and of itself, illustrates the transformative power of the women-only carriages and how this design feature can be perceived as both a measure of moral progress and a move towards more inclusive urban development in Cairo. Now that women-only carriages have been used to encourage public engagement, other aspects of the city can be analysed in order to continue redesigning and positively transforming both societal and institutional relationships within Cairo.

Originally published on The Global Urbanist

Are we just reflections of ourselves?

by Kate Moyer

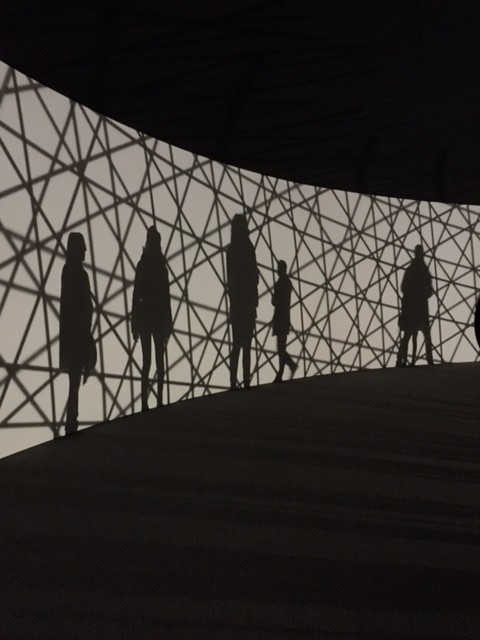

I was in Paris in January and was especially moved by Olafur Elliason’s exhibition Contact for the way in which it dissolves our individual relation to time and space. Elliason’s piece orchestrates a journey through unique rooms that aim to distort and question what is real or a reflection. The above image is taken from a walled room of mirrors, which projects and enlarges the shape of body.

Continuing the Task of Translation: Narratives and Design Studies

What follows are responses from those who attended the March 7/8 symposium Narratives and Design Studies at Parsons, sponsored by the MA in Design Studies programs. The conversation continues!

Design Can’t Do It All

Salem Tsegaye

The theme of narratives at this year’s symposium was quite fitting for a field tasked with interpreting, defining, and delineating design. The last—the task of delineation—is often the most difficult. While advocating for the crossing of disciplinary boundaries, we face the challenge of drawing parameters for a continually evolving, expanding domain. Many will argue the field of Design Studies is less about drawing parameters and more about exploring possibilities, but I would counter that the former holds equal significance. You see, if we don’t actually begin to say, “No, that isn’t design,” design scholarship becomes a futile project, and design, as title, will only be repeatedly co-opted for commercial interests.

The Mexico Biogas Program with Alex Eaton

The Mexico Biogas Program with Alex Eaton

In complete solidarity with panelist Alexander Eaton, I draw the line at social design. Think about it. If this is supposed to mean design that has some sort of positive social impact, then we should all be worried, because it implies that this do-good mentality is absent in modes of creative intervention that don’t share this name. This mentality, as ethical code, should be infused into existing design practices, not created into a new, separate one. Social design also attempts to make novel this idea of social change, which has existed for decades through the tireless work of humanitarians, community organizers, educators, etc. While professional designers undoubtedly bring technical expertise and a fresh perspective to the table, they too are operating within a broken system. In the absence of funding, scaling projects becomes an impossible task, calling into question (in this context) design’s innovative quality.

I use this response as an opportunity to say we do ourselves a disservice by validating the renaming of design into “__________ design” simply because it incorporates some new element from some other practice, discipline, or field. Certainly that isn’t the intention in our advocacy of interdisciplinary work, but we should err on the side of caution with this naming; otherwise, design will slowly lose credibility and meaning. The reality is design can do a lot, but it can’t do it all. It is our duty as scholars to be clear about design’s finite capabilities in these broader narratives.

Rethinking Terms

Laura Wing

In his talk on Narratives of History at the Design Studies Symposium Peter Hall proposed: “how it works is more interesting than what it signifies.” We can think of this in matters of the configuration of things. An example from our weekend, how woven and knit buildings and garments work differently in relation to environments and the body than, say, steel. And this generative capability of the ‘thing’, with its affordances and limitations (its agency), may be more interesting than what it signifies (gender, subversion, strength). Thinking further, even around the acts of ‘making-up’ and ‘making-real’—how these acts of design ‘work’ may be more useful to consider rather than what they signify. This is a way of rupturing and rethinking history, as Hall discussed. But I wonder what ‘opportunities to be otherwise’ might occur if we were to extend this consideration to language. I am specifically thinking about instances throughout the conference when certain terms—what they signify—took the conversation in a direction. An example might be the term social, that what it does in scripting and limiting conversations is more interesting than what it has come to be defined as. What might happen in purposely reconfiguring or inverting the term, what other conversations might be had?

Consider the terms used to frame distinctions of agency as either ‘staging an opportunity’ (Sean Donahue) or ‘joining a discussion’ (DESIS lab). More specifically, how the language works to frame the (design) opportunities in relation to artifice vs. opportunities in relations to persons.

How could the image of the rhizome or of the taoist diagram of the body translate into the use of language—moving away from fixed meaning and seeing possibilities for fluidity and motion?

In her opening remarks, Susan asked us to consider: “Where is the site of agency? Where is the gesture?” I want to talk about communication and language as one possibility.

Questioning Agency, Identifying Constraints

Rachel Smith

Unsurprisingly, the notion of societal structural constraints was raised by the sociologist at the table. I understood this notion to be the walls (ideologies) within which our living decisions must be made, but also the constraints within which design must work. The question is whether designers have the capability to work outside or push beyond these underlying structures in order to provide agency otherwise denied by existing structures. So the question is: what makes design the rare tool capable of expanding the ideologies or logistical restrictions that control how policy is formed, how people see the world, and what opportunity there is to rethink supposed “givens”? Lara spoke about the limitations of working within the semester schedules and the difficulty in maintaining relationships with communities after grant funding runs out. These, as Elzbieta pointed out, are structural limitations directly impeding design’s agency. Focusing on these particular examples, how can we move beyond the tedious but very real constraints of the academic and non-profit sectors in order to push the work undertaken as and with students into the realm of the real and permanent? And more generally, how often do designers truly provide agency for exceeding the obscured bounds of societal structure, and how much of design is produced to tacitly reinforce them?

Here are more thoughts on agency from Chris Bull, Professor of Engineering at Brown University:

An action supporting agency is creating an “enabling environment,” which ties to Sean Donahue’s mention of “activation of latent agency”.

One would hope that the elemental forces of society and technology might align and push/pull towards a common goal. Alex Eaton’s assertion that businesses are planning 20 years out in a very real sense; the rest of us are not. They are on to the how and we are still discussing the what.

From designer Marina Melani, an attendee:

I do have a comment regarding specifically one of the presentations, but that can be applied to most of them. I was particularly interested in Sean’s presentation, when he talked about the design of the Doritos’ bag, which exemplifies how design can encourage/discourage consumers to do something, to take actions. So obviously, as designers, we have a huge responsibility. (This was also later discussed with other presenters.)

The previous weekend I had a disappointing experience at the Museum of Science and Industry (Chicago). I enjoyed an amazing exhibit called “you, the experience” which talked about how our body works, and also about health. It explained how portions have become bigger in the last decade, and it really succeeded in making you aware of eating healthier and exercising more. I spent about an hour on this exhibition, and it had a great impact on me. The impact was diminished when I walked out of the exhibit, and three steps from it, I found a huge range of vending machines, offering nothing but unhealthy snacks. I know vending machines are “a big issue” in this country, but it just didn’t feel right, I felt deceived somehow. So I wonder, what’s the point of all the theory when afterwards we don’t act accordingly? If I had been one of the curators, I would have definitely been more careful about that “detail”, that at least for me, meant losing credibility of the exhibition.

All in all, my point is that the importance lies in more than making the right design decisions to encourage positive results, but also in keeping the right attitude as a professional and as a person, otherwise we lose our credibility.

Design, Agency and Autonomy

Verónica Uribe

Defined by the dictionary as the capacity to act otherwise, the term agency and its concept suffers important variations among disciplines. In social and political science as Elzbieta Matynia pointed during the symposium, agency is understood as the capacity to generates radical change in one´s own life. Hence although agency is related, it is also different from the notion of well-being and the notion of choice or option.

In design, agency is mostly understood as options, more contemporary theories in design have approach this notion from the capability approach. Sometimes, however, important features of this approach are left aside. Many social design projects for example tend to oversee in its goals settlement that agency does not necessarily means well-being. These projects tend to focus in the well being of a community leaving aside the agency aspect of the individual. That may leave important moral aspects out of consideration in the problem definition. As Amartya Sen[1] states: “the conception of person in moral analysis cannot be so reduce as to attach no intrinsic importance to this agency role, seeing them ultimately only in terms of their well-being” (p. 186)

One particular sphere where agency is important is in the person’s own life. Although well-being is deeply related to agency and choices about a person´s own life, as Sen points:

This does not however, imply that the well being information it self could capture the important features of agency, or acts as its informational surrogates. (…) Even when the impact is positive, the importance of the agency aspect has to be distinguished from the importance of the impact of agency on the well being. (p.186)

As a said before, others social design project reduce the agency to mere choices in the sense of physical possibility or access to the public sphere for example. The danger in these cases is to take agency for grounded when not physical restriction is around. However some agent may have less freedom in the choices between A or B even when neither is physically blocked form taking an option—it might due to cultural, gender or linguistic restrains among others, as Phillip Pettit sustains in his article Agency Freedom and Option Freedom (p. 390)

Summarizing, I think the notion of agency that comes from social and political science is relevant to design because it, in a way, challenges the usual notion of social design and the role designers have in public policy making. It also deals with problem definition´s issues in design. Some broader questions that this matter raises are: Can design address the moral aspect of autonomy? How? Furthermore, taking Alex Eaton statement during the event, if design is inherently social, shouldn’t it necessarily aim to this kind of agency?

Bibliography:

Pettit, Phillip. “Agency Freedom and Option Freedom .”Journal of Theoretical Politics. 15.4 (2003): 387-403. Web. 11 Mar. 2014.

Sen, Amartya. “Well-Being, Agency and Freedom: The Dewey Lectures 1984.” Journal of Philosophy . 82.4 (1985): 162-221. Web. 11 Mar. 2014.

[1]Amartya Sen is one of the main thinkers of this new economical and philosophical approach called the capabilities approach.

A Problem with Participatory Design

James Laslavic

The symposium touched on hidden problems with the well-intentioned drive in Western design to make things universally accessible. Namely, there was discussion about how that pursuit often leads to taking things out of the community-owned sphere and making them commodities.

However, I couldn’t help but notice how it all still failed to really involve the affected communities in the act of defining their problems, and seemed to play a mostly decorative role when brought into the design of solutions. In the discussion of “participatory design” and the “participatory spaces” that it works in, it still all felt like the communities were not quite viewed as being a genuinely insightful source of solutions. I have issues with the idea of participatory spaces because of how they can be said to effectively quarantine the participation they intend to generate. It is as if designers have begun to realize that involving communities is desirable, but still can’t help but view things in prescriptive terms.

To end, I’ll quote Keely McCaskie, a friend with whom I was discussing this because I don’t think it can be articulated better: “I’d say that designers (and ‘development specialists’ and whoever) are the ones who should consider themselves ‘participants.'”

idBrooklyn

As part of her thesis Sarah Lillenberg will tackle the implications of participatory design by looking at idBrooklyn, a cultural identity project. Here is her article that takes a look into idBrooklyn.

Why We’re Inviting Everyone to Help Visualize Brooklyn’s Identity

Part of what we love about Brooklyn is its “humpty-dumpty” history of cultural pioneers and makers. From Spike Lee to Woody Allen, Jay-Z to Talib Kweli, pizza slices to ramen burgers, brownstones to water towers, Jean-Michel Basquiat to Mickalene Thomas, artists in Brooklyn represent a dynamic nature that is at times too elastic for verbal explanation.

While Brooklyn’s diversity through thought, talent, and ideas are celebrated, its differences also cause a question of identity. Many people hold tightly to their Brooklyn roots and heritage. But how does Brooklyn manifest itself as a unified area with such grand diversity? Eyewitness News originally posed the question in regards to Brooklyn branding as such: “If too many people call themselves “Brooklyn,” what does “Brooklyn” mean?”

Ring in 2014 with Małe Instrumenty: The Politics of Tiny Instruments in Poland

This New Year, as we emerge from the season of sales and the scourge of shopping, Małe Instrumenty offers a different kind of gift: music played on toy pianos. Yes, Virginia, toy pianos. Toy pianos, children’s music boxes, and found-object instruments, played by Pawel Romańczuk, Marcin Ożóg, Tomasz Orszulak, Jędrzej Kuziela and Maciej Bączyk, the members of Małe Instrumenty who hail from Wrocław, Poland, where I taught last summer.

I’ve told the story of how I came to know about Małe Instrumenty to anyone who will listen and wrote about the band briefly on NSSR’s blog Public Seminar.But it was only over this holiday break that it dawned on me that their project was, in fact, quite political. Where late 20th-century Polish theater and performance was a refusal of the institutionalized repression of freedom by a corrupt Warsaw Pact government, Małe Instrumenty offer a modest yet powerful rebuttal to another kind of institutionalized control—the neoliberal rule of acquisition, accumulation, and social atomization.

During the 1970s and 80s in communist Poland, actors leveraged the power the everyday in the face of the seemingly intractable power. In Performative Democracy, my colleague and friend Elzbieta Matynia offers an instructive history of what she dubs the Young Theater movement. Among them were the Eighth Day Theater, which produced a performance in a blood donation facility in Łódź that spoke to the routinization of social violence (1) and the Warsaw-based Academy of Theater, which used apartment buildings as stages, enlisting their residents as performers (2). Groups such as these that made it possible for ordinary citizens to speak about their lives and played a critical role in defeating the forces of censorship.

Today, I see Małe Instrumenty as offering another kind of resistance. (Though I must admit that their music had so overwhelmed my senses that it took a while for me to recognize it.) First, there is the very fact of their decision to make music with discarded toys. This is a larger idea than simply salvaging the casual products of capitalism like Barbie pianos and other plastic instruments intentionally made to be short-lived. Małe Instrumenty recuperates the joy of childhood and our lost knowledge of how to make do. Which brings me to my second point: the sheer inventiveness they bring to the notion of an instrument. When I watched Pawel draw a bow over a series of emptied tin cans nailed to a stick and produce the vibrato of a violin, I was once again struck by the possibilities we can find in things, derive from things—things in wise hands.

Some I know would not call hand-made instruments “design” and would characterize the members of Małe Instrumenty as artists. But perhaps this is design after all, just done in reverse. When Małe Instrumenty take the detritus of mass production (toys, tin cans, bicycle bells), give it new life, and distribute it on a mass scale through media like YouTube they seem to render such distinctions moot. Małe Instrumenty are sound designers, object designers, and if our mutual friend Agata Gniebna has her way, social designers. Agata told me she wants to raise funds to build a giant-sized toy piano in one of Wrocław’s public spaces, so children can play it and play on it. It may be that the real gift of Małe Instrumenty is their recognition of the power of scale—always an element of design.

-Susan Yelavich

1. Elzbieta Matynia, Performative Democracy, (Boulder, Colorado: Paradigm, 2009), p. 21.

2. Ibid, p. 26.

Students Respond to MoMA’s Design and Violence Site

Violence and Virtue: Artemisia Gentileschi’s “Judith Slaying Holofernes”

Uffizi Gallery, Florence

Inspired by the Museum of Modern Art’s experimental web exhibition Design and Violence, students in Susan Yelavich’s “Design Fictions” course spent the last weeks of the fall semester discussing and responding to the fictions and facts of violence. Among other things, they debated whether design is by nature violent and the efficacy of addressing violence through critical design in the context of a museum’s blog.

For the site, co-curators Paola Antonelli, Senior Curator of Design and Jamer Hunt, director of Parsons’ MFA Transdisciplinary Design program, selected artifacts variously designed to “hack/infect, constrain, stun, penetrate, manipulate/control, intimidate, and explode.” Among the pieces chosen are the infamous 3-D printed “Liberator” gun, a generic box-cutter, stiletto heels, and a fragrance designed from cage fighters’ sweat. Experts the likes of Mabel Wilson, Camille Paglia, John Hockenberry, and Rob Walker offer their ruminations on one specific object. (Full disclosure, Yelavich herself is one of the commentators; see here) Now those expert observations are stimulating a lively public conversation, which the following Parsons graduate students are part of:

The Mythology of a Fraught Architecture

Some ways down an unnamed offshoot of Highway 413 in the small surf village of Rincón, Puerto Rico is a surprising structure, the decommissioned Boiling Nuclear Superheater Reactor—colloquially known by its friendly acronym, BONUS. I first encountered the building—a hulking, futuristic dome with a tarnished mid-century-aqua façade—while vacationing a few years ago on the recommendations of some surfer friends. They gave the town high marks, if not for the waves than for the accessibility of Rincón’s other tropical offerings—cheap bungalows, roadside burrito stands, a lack of paved roads—that make the town seem far more exotic than the two-hour plane hour plane ride suggests. The landscape did not disappoint; all the visible signifiers of casual, unencumbered beach town were there: shanty motel compounds, oceanfront villas-for-rent, barefoot, sunburned surfers milling on the corners. Until I took off along the beach away from town, not an aesthetic detail had contradicted my preconceived notions of the place, and certainly none pointed to a nuclear history.

Social Impact Design: Sistema Bioblosa

Using the often-overlooked technology of bio-gas energy sourcing, Alexander Eaton, CEO and co-founder of Sistema Bioblosa, employs simple and informed design strategies to empower impoverished farming communities. A key speaker at the A Better World by Design conference held in Providence, Rhode Island, this past September, Eaton presented the benefits that Sistema Bioblosa provides for small-scale farmers in rural Mexico.

Central to the Sistema Bioblosa model is the biodigester, which enables farmers to convert organic waste into renewable energy and organic fertilizer.

The design of the biodigester itself is an adaption of large-scale technology that is utilized by industrial farmers. In contrast to the older stoves that took months to build, Eaton’s biodigester can be assembled without technical assistance in an hour or so. It is comprised of a fifteen-foot long bag made of rough synthetic plastic, completely enclosing an anaerobic environment, allowing for the bacteria in the waste to flourish and convert to biogas and fertilizer. Connected by tubes, the converted biogas transfers and collects in another bag, which is lead through a pipe into the home for use in the kitchen or bathroom. A second tube connects and funnels the liquid organic fertilizer to an exterior tank. The manure produced by two cows or six pigs per day can issue a cubic meter of biogas, equivalent to 2.2 kWh of electricity. Regarded as a long run cost saver the possibilities inherent in this design enable small family farms to escape the poverty cycle. Eaton and his team of technicians travel to the family farms that are interested and provide individual training for the installation and use of the biodigester. Often the outreach and interest spreads throughout the community of local farms. Moreover, return visits allow the Sistema Bioblosa team to gather feedback, which Eaton identifies as imperative to the continued success of their work.

Promoting renewable energy and environmental development, Sistema Bioblosa works to instill the knowledge of managing resources that is essential to the future of farming in Latin America. By transforming materials and saving energy, the technology and design of the biodigester raises the standard of living for those who use it. Making the benefits of this biodigester accessible to all rural famers in marginalized populations ensures that the social and environmental impact of Sistema Bioblosa is far reaching. The model of Eaton’s Sistema Bioblosa encourages better waste management for small farmers and the rural poor. In doing so, they are helping to foster organic agriculture, improve health conditions and reduce greenhouse gas emissions, mitigating the risks of global climate change. By improving waste management and generating sources of renewable energy and organic fertilizer, Sistema Bioblosa serves a defining role in the movement towards global sustainability.

The Strange Attractor at the End of Human History

(Second year Design Studies student Finn Ferris gives an insightful review of Douglas Rushkoff’s book “Present Shock” and touches on many of the pressing issues of today’s ever-accelerating digital culture.)

It’s not the end of the world in the traditional sense — but it might be the end of traditional sense. Inspired nominally by Toffler’s influential Future Shock but more reminiscent of Lasch’s Culture of Narcissism in its scope, Douglas Rushkoff’s new book, Present Shock, takes a broad survey of the multi-generational shift towards all things instantaneous and incoming. From television remote controls to smartphones, gadgets are implicated in the degeneration of our collective attention spans and increasing inability to untangle what’s happening right now and deal with whatever comes next. The promise of the internet to connect us all to each other and to the things we want (digital and material) continues to drive the development, sales, and use of internet-connected devices. Rushkoff argues for a reevaluation of this scripted response. But, the promises of more productivity, a more efficient democracy (don’t miss Newt Gingrich’s smartphone musings on YouTube) and access to anything anywhere are so appealing. Of course we want this. What else is there?

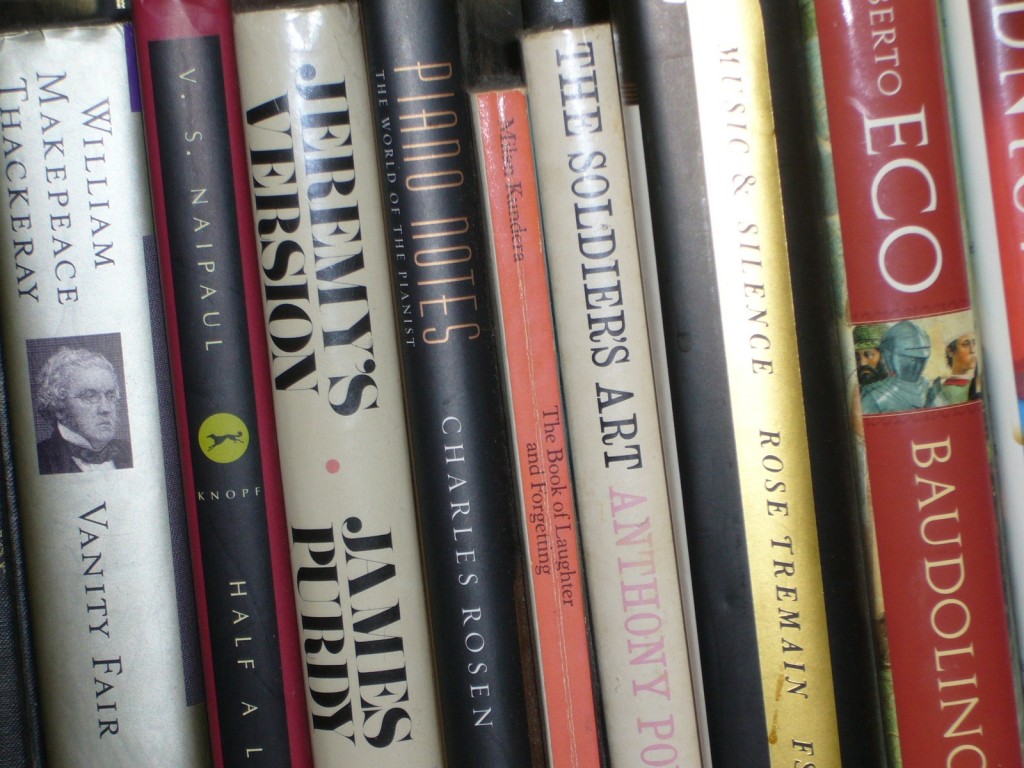

A Very Eclectic (and Personal) Reading List

I make a habit of keeping track of what I read for literary (and not-so literary) pleasure. It started as a way to share favorites with students and friends when memory fails as it often does. (I can remember what I read five years ago, but don’t ask me what I read last month.) Memory not withstanding, this list—which is emphatically not canonical—has over time become an archive of writers I admire, and not incidentally, places and countries I’m drawn to, have lived in and can’t get back to fast enough, or have never laid eyes on in the first place. It will be obvious to anyone who cares to read on that, in fact, I’m not as well traveled a reader as I’d like to be. There is an embarrassing paucity of titles from the southern hemisphere, to name just one region. I am clearly a global provincial—something I plan to remedy by reading even more.

[Susan Yelavich]

Remembering Bill Moggridge

Cooper-Hewitt’s brief video honoring Bill Moggridge.

What is design? This is a central question we’ve been asking ourselves over the past few weeks as novices in the field of Design Studies, and perhaps the answer will become clearer as we continue to grasp the many concepts and ideas of renowned voices in design thinking. To contribute to our growing knowledge in the field, I’d like to use this opportunity to honor the late Bill Moggridge, designer and design thinker extraordinaire. (more…)

The Double Profile of Design Studies

FROM THE DIRECTOR

In an earlier posting, I promised I’d speak to the question of who the Masters in Design Studies program has been designed for. But to do that I find myself asking: How is this program designed? Anticipating who will be attracted seems less the point than articulating what makes Design Studies attractive. I think student profiles are best left as silhouettes of avid writers, thinkers, readers and critics that can will take on dimension as they are filled. In the meantime, it seems more helpful to assess the character and characteristics of Design Studies.

For my part, I see Design Studies in terms of two broad perspectives—one that focuses inward on the nature of design and one that looks outward to the circumstances that shape it. This is, of course, risky in an age when dualisms of all sorts (mind/body, we/them, etc.) have been all but discredited. Nonetheless, if we accept the idea that these two halves can be stacked and layered, and that they will inflect each other by virtue of proximity, then perhaps the divisions I outline below will be seem less arbitrary.

The Difference between Design Studies and Design History

FROM THE DIRECTOR

As promised, this is the second in a series of posts in which I answer hypothetical questions about Parsons’ M.A. in Design Studies. Of course, the first questions you might have (I know I would, especially if I were moving) might have more to do with what life will be like on a day-to-day basis in New York. Realistically, this may be too subjective for me to tackle here. There’s only so far I can walk in imaginary shoes. So while you look at Google Earth and take the cultural pulse of the New School and Parsons, I’ll tackle the territory I do know—the content and nature of the program. And given how young design studies is as a field, one of the first things you might want to ask is this:

WHAT’S THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN DESIGN STUDIES AND DESIGN HISTORY? (more…)

What Is/Are Design Studies?

FROM THE DIRECTOR

If you’re reading this, it’s probably safe to assume you’re curious about Parsons’ new Masters in Design Studies. This is the first in a series of posts in which I’ll describe what’s unique about the program and try to anticipate some questions, beginning with:

WHAT (IS) ARE DESIGN STUDIES?

Design studies (like design) is a multifarious enterprise. A branch of the humanities, it comprises a wide range of critical perspectives on the meanings and values embodied in objects and places. It examines the forces that design exerts in, and on, the world—forces design sets in motion but does not control. Parsons’ Masters in Design Studies program places particular emphasis on four points.

(more…)

Visiting TVAD

IMAGE: Flickr/Hil LICENSE: CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

I recently visited the TVAD Research Group, based in the School of Creative Arts at the University of Hertfordshire, which researches relationships between text, narrative and image, and which also has a blog. (more…)

NORDES, Norway, Design (and not in that order)

By Susan Yelavich

Oslo side street. Photo: Susan Yelavich

Oslo looks to be a very different kind of city, even for a reasonably well-traveled New Yorker. It seems largely residential populated by six to eight-story buildings (many in a restrained, neoclassical style others in Scandinavian cottage form) in pinks, blues, yellows, reds, and white, framed with trees and parks of the deepest green.

Construction around the harbor in Oslo. Photos: Susan Yelavich

Yes, there is all the new construction on the harbor, which speaks to a more rapacious Norwegian prosperity. But otherwise filthy lucre is hardly in evidence. You don’t see it in people’s dress, which tends toward practical sport-driven garb. There is almost no aggressive advertising outdoors and little in the way of attention-getting shop displays. All in all, a feeling of self-effacement dominates, which makes for an odd kind of assertiveness.

Equally, the NORDES 2107 conference was marked by calls for modesty. They were evident in almost all of the keynote speeches. Yoko Akama spoke of “philosophies of absence [that] take non-being or nothingness as the necessary grounds for being” as relevant to truly conscientious design. Even Westfang took exception to ‘design exceptionalism.’ Thomas Binder embraced the idea of design’s ‘weakness.’ All this at a conference of designers dedicated to participatory design, co-design, and social change. (Even in the workshop I co-led with Nik Baerton, Virginia Tassinari, and Elisa Bertolotti, participants cited their solitary acts of writing as the most satisfying part of the collective storytelling process.)

However, none of this amounted to calls to return to the Post Modern 1980s when architecture and design withdrew from the social sphere after modernism’s failure to ‘change to world.’ It was rather a recognition that the ambition to ‘change the world’ is ridiculously hubristic if seen as a project of design alone. Well-intentioned design efforts to care for refugees or house the homeless can be tacitly complicit with the political conditions that make them possible. Mahmoud Keshavarz and Jocelyn Bailey, respectively, made the case that designers are often put in the untenable position of perpetuating greater political systems of injustice in their efforts to help. For example, in providing shelters for those the state refuses to care for, designers risk confirming the state’s estimation that these are people unworthy of the resources we ourselves take for granted. In that view, refugee housing could be considered second-class shelters for second-class citizens.

Notably, though, there was a scarcity of propositions as to how to contend with design’s relative powerlessness in this difficult present when democracy and other forms of political agency are under threat. If retreat isn’t ethically tenable, then what is? Here Evan Westfang (whose own work has to do with making public data both public and visceral) offered an interesting response. He called for a return to ‘normative design’ – not design-for-design’s sake, the stuff of international design fairs and the like. The ‘norm’ of design that he referred to is it’s inherent generosity.

Oslo Opera House, Snøhetta, Wikipedia.

That said, I’m not sure he or anyone else in Oslo would find that generosity where I did during my brief visit, given how skeptical we’ve become of design that is anointed ‘successful.’ I’m referring to my experience of Snøhetta’s Oslo Opera House (2008), which yielded so many unexpected epiphanies—epiphanies, which I suspect are not mine alone. Walking up, on, across, and down its sloping planes, you are never quite sure whether your feet are on the ground or in the air.

Oslo Opera House roof, Snøhetta, Photo: Susan Yelavich

Childhood and adult sensations were felt more than remembered. For me, at least, there was a palpable sensation of the risk that comes from playing in and on a space that seems illicit, namely, the roof. There was the pleasurable disorientation of losing any sense of scale while walking on a glaring white landscape akin to a desert; and the mysterious possibilities of hide and seek around its volumes that Michelangelo Antonioni captured on the roof of Antonio Gaudi’s Casa Mila (1912) in his 1975 film “The Passenger.”

Jack Nicholson on the roof of Gaudi’s Casa Mila. Still image from the 1975 film “The Passenger.”

My conscience pricks me as I write this paean to the pleasures of feeling, to paraphrase Philip Johnson, my ‘molecules being rearranged’ by architecture. Yet, is this so selfish? The philosopher Jacques Rancière argues otherwise. He places value on “the possibility of being together and apart” because space for solitude has become “a dimension of social life which is precisely made impossible by the ordinary life… .”1 (Ordinary life, here, being the relentless bids for our money and our attention.)

Now Rancière is actually writing about the conditions in Paris’s poor suburbs where he sees a need for spaces and places that offer the dignity of solitude (not the despair of loneliness) for its residents, the very same people who designers are quick to gather into configurations of participatory design. But I would argue both situations – the collaborative and the solitary – are powerful frameworks for design and, that at its best, design creates conditions to be ‘together and apart.’ Even and especially on the roof of an Opera House, where seeing an opera isn’t required.

“Apart and Together on the Oslo Opera House roof.” Photo: Susan Yelavich

Aesthetic Regime of Art” taken from an edited transcript of a plenary lecture delivered on 20 June 2006 to the symposium, Aesthetics and Politics: With and Around Jacques Rancière co-organised by Sophie Berrebi and Marie-Aude Baronian at the University of Amsterdam on 20-21 June 2006. http://www.artandresearch.org.uk/v2n1/ranciere.html Accessed 6/20/17.