written by Anke Gründel

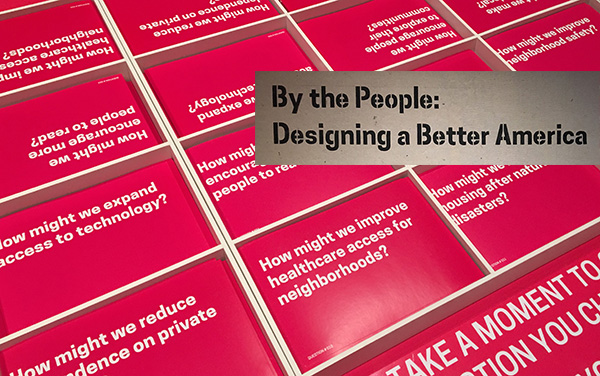

Interest in design is on the rise in the public sector, an apparent need the various design communities are working hard to fill. That is the main convergent message emerging from two recent design conferences, the Global Service Design Conference in New York City and the Politics for Tomorrow Conference in Berlin, Germany. Other than this apparent main point there was very little that remained similar. To make sense of the levels of discourse in these two recent events, perhaps it would make sense to first look at the disparate settings in which these two conferences took place.

The first of the two took place in early October 2015 in New York City. The Global Service Design conference was organized through the Global Service Design Network, an organization that aims at connecting the diverse strands and currents of the still somewhat novel field of service design. The private organization this year partnered with Parsons, The New School for Design in Manhattan, which lent its spaces and expertise to pull together and tend to the many professionals from across the world who streamed to New York and cure their jet-lags over coffee in the large Tishman auditorium of The New School’s University Center.

The first thing I noticed while shooting glances up and down the isles was that the service design population gathered there seemed to suffer from relative monochromatism that allowed a primarily Euro-American worldview to predominate, while engaging the occasional Scandinavian perspective. Certainly, among the speakers were also designers from Singapore and Russia whose perspective aligned all too well with the business-minded rationality communicated in success-and-solution-lingo. The relationship of the speakers to the crowd was dominated by mutual understanding and the profound belief that what connected everybody there was a desire to change the world with almost unilaterally agreed upon methods shared in an atmosphere of reciprocal back-patting. At some point a speaker asked the audience who amongst them considered themselves optimists or realists. Unsurprisingly, a forest of raised hands signaled the majority of the optimist camp, a visual marker for the rosy-future visions dominating this event. Few words of caution were uttered against this future-oriented designer optimism, understanding current pervasive social issues as problems to be solved by, through, and as design. If not critique then at least skepticism came from one of the very few non-designers at the conference.

Cameron Tonkinwise, a philosopher by training, problematized the temporal claims in many of the projects presented at the conference in that he pointed out the apparent piecemeal nature of service design as a project-based practice. While discourse around transformations predominated, there was no consensus that would have allowed for social accountability structures beyond the overall common built-in auditing practices of many design approaches. Once the (funding) clock has run out on most service design projects, there is little thought about who takes responsibility for the aftermath. In the absence of an overarching institution which could hold actors accountable and bundle aims for a future into a coherent whole, the market is dominated by a preponderance of small, middle and large design labs and lab-like organizations practicing social entrepreneurialism. One might wonder why a global conference of such scale, attended by hundreds of people in one of the world’s leading design universities – ironically part of the formerly Marxist New School – drew such an ideologically, professionally, and socially homogeneous crowd. Any mystery is soon resolved however, if one takes a look at the conference prices demanded by the Global Service Design Network. With rates of almost $1000 for non-member (the price of around $900 for members is only marginally more affordable) and around $300 for students for a two day conference it comes at no surprise that diverging opinions were neither desired nor encouraged. Surely, as a professional conference, the rationale was to create a context for practitioners to share, support each other, and create new connections, however given the general emphasis on public participation and the expressed desire to enlist a multiplicity of different stakeholders in co-creative processes the virtual absence of diverging opinions about the kind of future designers want to create was jarring. Needless to say, I left feeling rather disenchanted but at least with a realistic overview of service design and its constituency.

Two weeks later, a different continent, a different language and a different experience. Over the course of the two day conference, during which it rained non-stop under a sky so gray that it created the illusion of all-day dusk, around 90 guests attended the small and well-organized Politics for Tomorrow conference. While embedding design processes in policy-making and governance processes is gaining acceptance in the US as the altogether 29 government innovation labs would attest to, in Germany design’s legitimacy as public action tool is all but established. Indeed, in contrast to its neighbours Denmark, France, and Austria as well as fellow EU member states Spain, Portugal, the UK, and the Netherlands, Germany seems rather behind (presupposing the goal is governmental innovation) when it comes to identifying innovative methods for connecting citizens and the government.

To address this stated (and highly debateable) need for innovation, the organizers from Next Learning, an association focusing on creative transformation services, brought presenters from a variety of backgrounds, experiences, and approaches together to share their work. The only thing everybody had in common was their investment in political transformations. While most had an explicitly design-oriented focus front-lined by the usual suspects in these types of discourses, Nesta (UK) and MindLab (Denmark), there were also other organizations present whose formation by far predates the explicit articulation of design as a protocolistic action framework (in the form of design thinking or human centered design). Among them were Forum Alpbach (Austria) and The Young Foundation (UK) neither of which felt it necessary to explicitly use the label of design.

In contrast to the Global Service Design Conference what was surprising was that the guests were not only designers. Interspersed were also a handful of civil servants, academics, and those from the public sector tangentially engaged in creative practices. To be sure, there also were a select few civil servants present in New York, however their curated and innovation-focused opinions were not markedly different from the mass of cheerleading designers. In contrast, among the mere 90 people at the Politics for Tomorrow conference the vocally distinct non-designers shifted the discourse perceivably towards substantial critique and caution. Among the typical question as to how designers may help the government to recognize problematic relations between citizens and policymakers that perhaps remain irreconcilable with traditional methods, there also was a relatively strong critical attitude toward the practices designers employ to render such problems visible. Thus one of the most interesting tenets emerging from interactions between the audience and the presenters was the problem of methods as ends in themselves. Indeed, the dominant challenge to designer from those who had not yet bought into the “inherent value” of creative innovation techniques, pressured designers in the public sector to explicitly state their goals rather than merely discuss the value-adding aspect of their methodological toolkits. Interestingly, the critique of methodological overdetermination operated on different discursive levels and was sometimes vigorously debated. In one of the workshop sessions that typically followed the presentations, this problem of design methods emerged in all clarity.

I was participating in a workshop in which design as a primarily market-based practice was explicitly called into question. Yet despite this critical attitude, typical methods were nonetheless central to the session. Tasked with creating a network of characteristics for a healthy and supportive community, we were struggling to fill our stereotypical post-its with meaningful content that could be contained by the small sheet of colored paper. Unsurprisingly to me, this did not lead to much and we all got frustrated over the methodological format. Post-its can be useful for getting thoughts out quickly, yet they are no replacement for vigorous discussion, as we all realized. As most design methods aim at reducing conflict and thus obfuscating power dynamics inherent to any social group, one has to ask whether design can ever unproblematically become part of the public sector. While no doubt practical, as a civil servant from the Düsseldorf municipality remarked, practicality of design methods alone is not reason enough to discard a whole system especially given the inability to accountably foretell contingent outcomes. In that private services are not at all like public services in scope, necessity for accountability systems, and heterogeneity of service recipients, the public sector has other requirements than the market-oriented dynamism inherent in private services. Service customers are construed as entirely different entities in the private versus the public sphere. Whereas private services encounter consumers, their public counterparts face citizens, a crucial definitional distinction in which whole hosts of assumptions are embedded.

In short, this conference was rife with diverse sometimes optimistic sometimes critical positions and contra to the predominantly enthusiastic Global Service Design Conference, in Berlin there was a broad spectrum of critique and a variety of discursive levels in the gamut of problematizations ranging from future research in climate matters, biodiversity, immigration, to business mentality and entrepreneurship which was at times fiercely challenged as excessively neoliberal. Design was introduced not only as a set of methods but as an alternative to technocratic expert panels especially when it comes to the problem of funding and directing scientific inquiry. Discussed were also power dynamics of organizational change in that questions were raised over who wins or loses if design gets integrated into established institutional structures. It was refreshing to hear such a reflective position as we tend to ignore consequences of organizational change we support. Certainly, some will benefit, but others will lose their jobs or their representation. As much as the design debate wants to align itself with discussions around the changing nature of democracy, any potentially undemocratic power dynamics inherent to the political design movements are rarely problematized.

Admittedly, the critical tenor of this event may have been impacted by the general cultural environment – as a German living in the US, I cannot deny that I felt positively liberated from the burden to filter my own critical attitude when it comes to interacting in the design field. But I cannot help but feel that design could only benefit from harsh-but-productive critique. All concerns for legitimacy aside, if design is to become a practice that does not merely reproduce hegemonic neoliberal problems but that offers a real alternative to New Public Management as it was presented in this event then it cannot shy away from involving those who remain skeptics about why design delivered by designers should reconfigure government.

Anke Gründel researches the entanglement of conception of the state, citizenship, and design practices inherent to the current proliferation of design-led innovation approaches in governance practices. She interrogates design expertise vis-à-vis the history of technocracy within liberal democratic systems. She received the Parsons Student Travel grant to document the Politics for Tomorrow Conference.

The Strange Attractor at the End of Human History

(Second year Design Studies student Finn Ferris gives an insightful review of Douglas Rushkoff’s book “Present Shock” and touches on many of the pressing issues of today’s ever-accelerating digital culture.)

It’s not the end of the world in the traditional sense — but it might be the end of traditional sense. Inspired nominally by Toffler’s influential Future Shock but more reminiscent of Lasch’s Culture of Narcissism in its scope, Douglas Rushkoff’s new book, Present Shock, takes a broad survey of the multi-generational shift towards all things instantaneous and incoming. From television remote controls to smartphones, gadgets are implicated in the degeneration of our collective attention spans and increasing inability to untangle what’s happening right now and deal with whatever comes next. The promise of the internet to connect us all to each other and to the things we want (digital and material) continues to drive the development, sales, and use of internet-connected devices. Rushkoff argues for a reevaluation of this scripted response. But, the promises of more productivity, a more efficient democracy (don’t miss Newt Gingrich’s smartphone musings on YouTube) and access to anything anywhere are so appealing. Of course we want this. What else is there?

(more…)