At the Design Studies Symposium at Parsons The New School for Design the two speakers invited on the first day were: Peter Hall, design writer and professor at Griffith University, Queensland, who flew down from warm and sunny Brisbane into freezing New York, while the keynote speaker was essayist, critic and professor at Columbia University, Phillip Lopate, best known for his writings on New York.

After Susan Yelavich, director of the MA Design Studies program, introduced the themes that would be addressed in the course of the two days—design and narratives of gender, agency, social engagement, artifice among others—Hall took the stage and addressed his topic, Narratives of History.

A gripping argument about an alternative approach to writing design history followed. With the risk of sounding simplistic, in a nutshell, Hall questioned the inclination of history-writing to be too canonical. “You can’t learn about the mountain range by studying the peaks, and who decides which peaks to study?” asked Hall.

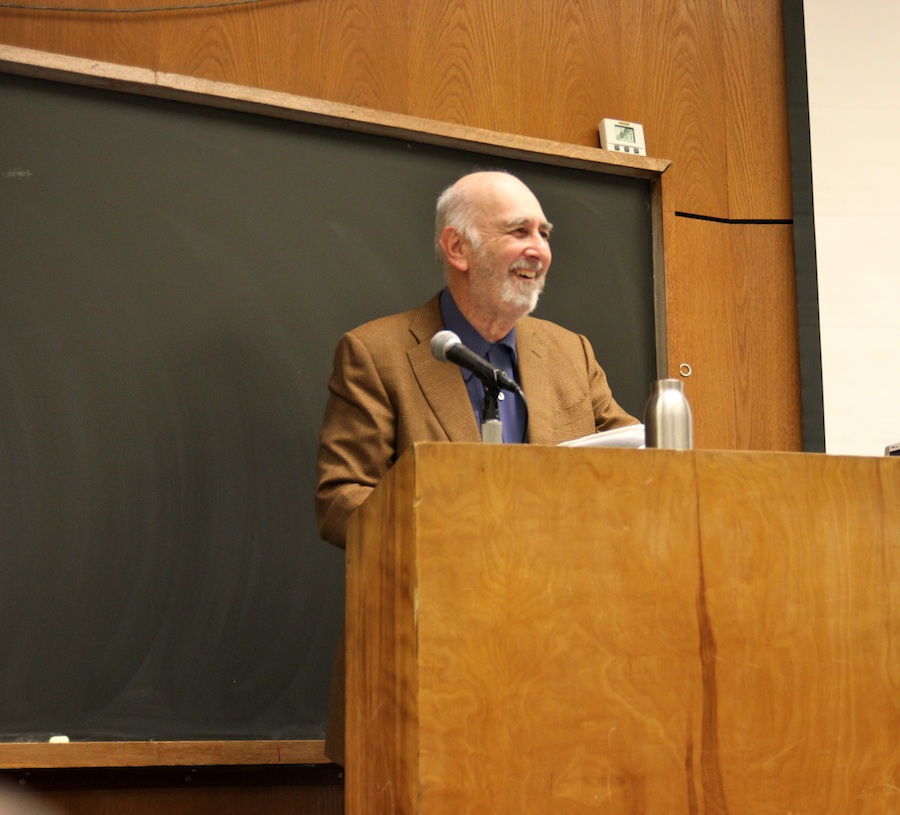

After this thorough, intensely academic and design centric session, Lopate took the stage, carrying with him a tall stack of books.

Narrating Place

As a significant change to this conversation, Lopate’s session was a page out of a completely different book. An elegiac but charming book reading session ensued. It reflected on how narratives of place are narratives of memories, values and consequently of design.

He began with a note of caution: “This is going to be a Zibaldoni, a hodgepodge.”

Lopate’s readings were centered around the notion of the street as a stage setting. Among the several references that he made to illustrate how narrative emerges from place were, “Love at last sight” in the words of Walter Benjamin in his book on French poet Charles Baudelaire. “Two people.. meeting.. passing.. I could have loved that person.. okay bye!” he explained. He reminded us of Emile Zola’s The Ladies Paradise and Jane Jacob’s The Death and Life of Great American Cities. “Remember that famous passage about the choreography of the street and in this case of Greenwich Village,” said Lopate.

He went on to read a poem by the Greek poet Constantine Cavafy, which perfectly set the pace and the mood for the readings to come. It is reproduced here:

The Afternoon Sun

This room, how well I know it.

Now they’re renting it, and the one next to it,

as offices. The whole house has become

an office building for agents, merchants, companies.

This room, how familiar it is.

Here, near the door, was the couch,

a Turkish carpet in front of it.

Close by, the shelf with two yellow vases.

On the right—no, opposite—a wardrobe with a mirror.

In the middle the table where he wrote,

and the three big wicker chairs.

Beside the window was the bed

where we made love so many times.

They must still be around somewhere, those old things.

Beside the window was the bed;

the afternoon sun fell across half of it.

…One afternoon at four o’clock we separated

for a week only… And then—

that week became forever.

Lopate went on to read several of his own writings on New York, on the love-hate relationship between the two boroughs of Manhattan and Brooklyn, and it all tacitly amounted to a way of looking at cities as “a continuous transformation.”

In a spontaneous but perfect conclusion to the evening, Lopate seemed to have saved the best for last. It was prompted by a question by someone in the audience, who asked, “Within the context of a design symposium, do you think that a writer can contribute something unique to this discussion about a city?”

“Well the answer is probably not! But what I was hoping to do is to show the way, narrative can germinate from almost anything,” said Lopate, as he went on to explain himself via a passage from his book Getting Personal.

“We lived on the top floor of a five-story tenement in Williamsburg, facing the BMT elevated train, or as everyone called it, the El. Our floors and windows would vibrate from the El, which shook the house like a giant, roaring as his eyes were being poked out. When we went down into the street we played on a checkerboard of sunspots and shadows, which rhymed the railroad ties above our heads. Even the brightest summer day could not lift the darkness and burnt-rubber smell of our street. I would hold my breath when I passed under the El’s long shadow. It was the spinal column of my childhood, both oppressor and liberator, the monster who had taken away all our daylight, but on whose back alone one could ride out of the neighborhood into the big broad world.”

“… it’s all design in a way.” Lopate shrugged and concluded with a childlike smile.