Issue 5 2021 Long Essays

The Hamilton Fountain: “Let Him Be Forgotten”

Bill Shaffer

Fig. 1 The Hamilton Fountain Riverside Drive, New York City, September 19, 1909. Robert L. Bracklow Photograph Collection, PR 008, New-York Historical Society, 66000-1186.

The pandemic of 2020 has seen the widespread closure of museums and libraries, restaurants, bars, and other settings where New Yorkers normally gather, making city parks some of the few public spaces available to experience some sense of community. Without much else to do, New York City’s Upper West Side residents seem to linger a bit longer than they did pre-pandemic at the Eleanor Roosevelt statue at 72nd Street and Riverside Drive or further north at the Soldiers and Sailors Monument at 90th Street. Of those who choose to sit on the benches near the Hamilton Fountain at 76th Street, few know the fountain’s raison d’être and the long-forgotten Hamilton story (Fig. 1). Like countless other New York stories, though, it stands ready to be revealed to the curious.

The name “Hamilton” today is most associated with the overwhelming success of Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Broadway musical based on Ron Chernow’s biography of Alexander Hamilton. An aide-de-camp to George Washington in the Revolutionary War and the first US Treasury Secretary, Hamilton died an untimely death in a duel with Aaron Burr in 1804. At the height of the Gilded Age, however, it was another Hamilton, Alexander’s great-grandson Robert Ray Hamilton, who entered the nation’s consciousness and garnered headlines of his own.

On the morning of August 26, 1889, Evangeline, the wife of thirty-eight-year-old Ray Hamilton, stabbed the nurse of their eight-month-old daughter in a drunken rage while the family was on holiday in Atlantic City. From that moment, Ray’s fate became entwined with that of his wife, a pair of Gilded Age grifters: Joshua Mann and his mother, Anna Swinton; legendary New York City police detective, Tommy Byrnes; a future Secretary of State, Elihu Root; investigative journalist, Nellie Bly and John Dudley Sargent, an unstable Wyoming rancher and cousin of painter John Singer Sargent.

Beginning on August 27, 1889, the Hamilton scandal ran on page one of The New York Times, New York World, New York Tribune, and most other New York dailies for an almost-unheard-of thirteen straight days and was picked up each day by a vast majority of the four thousand other newspapers printed across the country. Ray Hamilton, a distinguished New York state legislator and prominent real estate developer, became a central character in the sordid tale that involved prostitution, illegal baby farms, assault with a deadly weapon, and bribery. One year after the stabbing, Ray was found face-down, drowned in the Snake River in the shadow of the Grand Tetons.

The Hamilton Scandal The story of the Hamilton Fountain involves the audacious scheme of Evangeline Brill, a Gilded Age prostitute and grifter, who conspired to swindle Robert Ray Hamilton, a great-grandson of Alexander Hamilton, held in Eva’s thrall. Her scheme included bigamy (Eva was in a common-law marriage to another man while married to Ray) and the illegal purchase of an infant who Ray was led to believe was his own child. Eva’s scheme began to unravel when she stabbed her daughter’s baby nurse. It came completely undone when Ray Hamilton mysteriously died by drowning one year later. After Ray’s death, the shamed and embarrassed Hamilton family bought Eva’s silence and publicly declared of Ray, “let him be forgotten.” Eva squandered the hush money and died a penniless alcoholic. Ray and Eva were buried ten miles away from each other in New York City–Hamilton in Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, Eva in Mt. Olivet Cemetery in Queens–their unmarked graves a bitter testament to their infamous affair and ignominious deaths.♦

It is not difficult to understand the public’s fascination with Ray Hamilton’s fall from grace. In the nineteenth century the Hamilton name was recognized by all Americans and almost universally revered—akin to the Kennedy name today. The news of Alexander Hamilton being shot by Aaron Burr in 1804 produced the same level of shock as the news of JFK’s assassination in 1963. The Hamilton name had continued in the public eye after Alexander’s death due to the work of Ray’s grandfather, historian John Church Hamilton, and Ray’s father, Civil War General Schuyler Hamilton. Ray’s mother, Cornelia, also hailed from prominent New York families as did his aunts, uncles, and cousins. They were all listed in the Social Register, well known in political and financial circles, and many were members of Ward McAllister’s “Four Hundred,” the pinnacle of New York society. Ray had muddied the Hamilton name and compromised the family legacy.

The Hamilton Fountain, completed in 1906, was not intended to be a painful reminder for the family about the downfall of one of their own. The impetus for the fountain began with Ray Hamilton’s Last Will and Testament, in which he stipulated that the executors of his substantial estate were to set aside $10,000 for the “purchase and erection of an ornamental fountain which I give and bequeath to the Mayor, Aldermen and Commonality of the City of New York.”1 Fountains to provide “water for man and beast”2 were in vogue in the city at the time: “The need for more fountains in this city, both drinking and ornamental structures, has only been partially supplied by generous and public-spirited men and women. There are a few memorial fountains, but a very few when it is considered what an exceedingly appropriate and useful thing a public fountain really is.”3

Nevertheless, eight months after Ray’s death, the Hamilton and Schuyler families filed a petition to the Mayor and Board of Aldermen that found its way into The New York Times. Titled “Let Him Be Forgotten,”4 the three-paragraph story related the family’s unambiguous opposition to the provision in Ray’s will that set aside money for a fountain because “such a memorial as the will designates would perpetuate a name that brought dishonor to the family.”5 The petition was set aside and the city’s search for a suitable location for the Hamilton Fountain proceeded, albeit very slowly. Indeed, the project lay dormant for twelve years.

It is perhaps not a coincidence that in 1903, only two months after Ray’s father passed away at age eighty-three, the three-man Board of Commissioners for the New York Department of Parks approved a site proposal put forth by the Department of Parks Landscape Architect Samuel Parsons Jr.6 The site selected for the Hamilton Fountain was not in one of the heavily trafficked public squares in lower Manhattan—City Hall Park, Madison Square Park or Union Square—but rather, in a more obscure location on the city’s Upper West Side, Riverside Drive at the end of West 76th Street. The location was far removed from the fashionable Murray Hill neighborhood near Gramercy Park where the extended Hamilton family had lived for a hundred years. On the Upper West Side, the likelihood of Ray’s aunts, uncles, or cousins passing by the fountain on a day-to-day basis was remote.

Fig. 2 Postcard. Riverside Drive and Park, c. 1900.

Riverside Park was less than thirty years old in 1903. Frederick Law Olmsted had developed a conceptual scheme for the park in the early 1870s and by the turn of the century, the park and Riverside Drive from 72nd to 125th Streets had become a popular destination for Sunday afternoon strolls and carriage rides (Fig. 2). The natural bluff that rose from the Hudson River below afforded spectacular views to the Palisades in New Jersey. The opening of the Ninth Avenue El in 1868, the first elevated railway in the city, would also bring thousands of new residents to the previously ignored enclave, and, in 1888, The West End Association, an organization of architects, builders, and real estate agents, published a pamphlet touting the up-and-coming neighborhood. Clarence True, a prolific architect and developer, published a glorified real estate prospectus7 in which he enthused that “to-day, Riverside Drive, with its branching side streets, is the most ideal home-site in the western hemisphere—the Acropolis of the world’s second city.”8

The plan called for the Hamilton Fountain to be fitted within a gently curved brownstone retaining wall that sat above a riding path in Riverside Park. The architectural firm selected to design the fountain, Warren and Wetmore, was in existence for only five years when they began work on the project. The commission was awarded to the firm just after the completion of their design for the New York Yacht Club on West 44th Street and just before they began work on their tour-de-force, Grand Central Terminal. Whitney Warren began his formal architecture studies at Columbia University in 1882 but left after a short stay. In 1887, he was accepted into the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, considered to be “the preeminent course of study for an aspiring American architect.”9 Warren returned to the US in 1894 without completing his studies.

Upon Warren’s return, he designed a house for a young lawyer, Charles D. Wetmore, an 1892 graduate of Harvard Law School who moved in the same social circles as Warren. By all accounts, Warren and Wetmore got along famously from the outset of their relationship and Warren, impressed by his client’s aesthetic sensibilities, proposed to Wetmore that they form an architectural practice. Warren would oversee the creative output of the firm and Wetmore would look after its financial interests. Wetmore agreed and their partnership began in 1898.

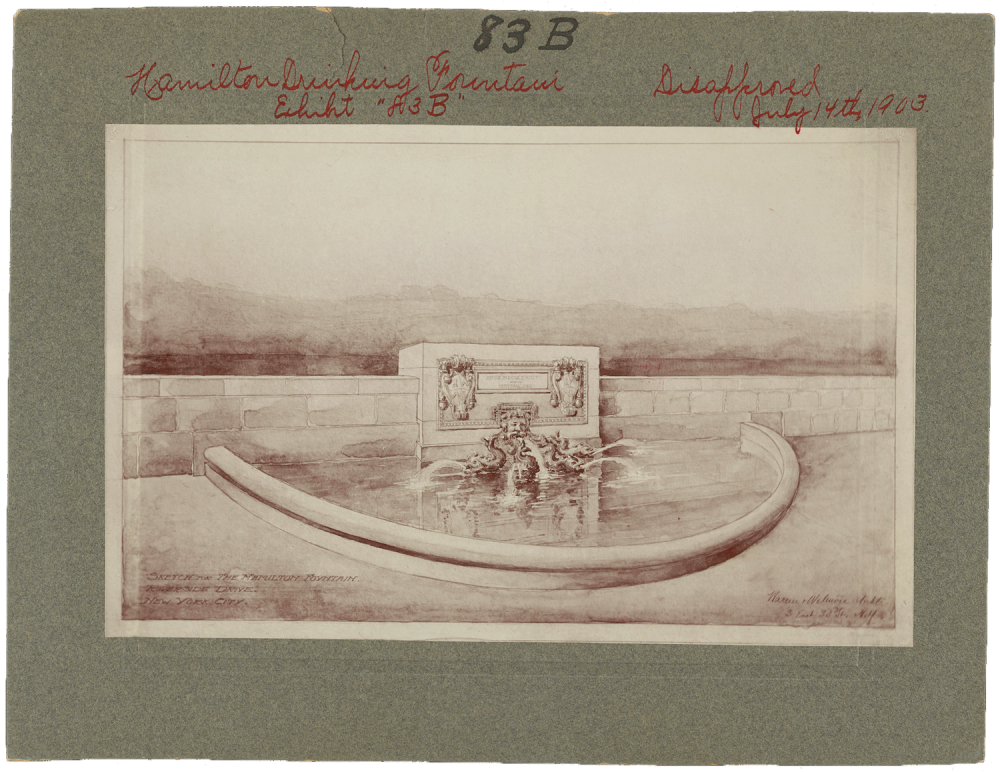

Fig. 3 Initial proposal for the Hamilton Fountain, 1903, rejected by the New York Art Commission. Architects: Warren and Wetmore. Collection of the Public Design Commission of the City of New York.

Warren and Wetmore submitted the first drawings for the Hamilton Fountain to the New York Parks Dept. Board of Commissioners in June 1903 (Fig. 3). The drawings were readily approved by the Parks Board and the project had one last hurdle to clear, approval by the New York Art Commission. The Art Commission, formed in 1898, was originally granted limited authority to “regulate artwork that was commissioned or donated to the city.”10 Mayor Seth Low expanded the role of the Art Commission in 1902, with the directive to “review all designs for public works in the city… including lamp post designs, signage, water fountains and fire hydrants.”11

The Art Commission consisted of ten pro-bono members: the mayor of New York City; the Presidents of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the New York Public Library, and the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences; a painter, a sculptor, an architect; and three laymen.12 The three-man committee charged with reviewing the submission for the Hamilton Fountain was chaired by Alexander Phimister Proctor, a sculptor noted for his expertise as a sculptor of animals. Proctor was joined by architect and psychologist Henry Rutgers Marshall, who gained fame as the author of Pain, Pleasure and Aesthetics in 1894, and Loyall Farragut, writer and son of Admiral David Farragut.13

Warren had gained a reputation as an enthusiastic proponent of the Beaux-Arts principle that called for an integration of the three divisions taught at the École: painting, sculpture, and architecture. Historical architectural forms, motifs and ancient allegorical figures were combined in ways befitting the dawn of a new century. As Warren explained, “Architecture is always an evolution. Of course, we use old styles, we can’t invent a new one, we can only evolve to a new one. So we are taking the best elements in the old styles, and we are attempting to produce from them what is suggested and demanded by our present conditions—a new American style.”14 However, none of the new-American-style philosophy so clearly articulated by Warren was evident in the first proposal for the Hamilton Fountain.

Warren and Wetmore’s first proposal called for a four-foot-tall granite stile to be centered in a two-foot-high brownstone retaining wall that bowed out from Riverside Drive to create a small, curved plaza. An inset panel, framed in egg-and-dart molding, contained symmetrical scrolled shields on either side with space for a chiseled inscription in the center. Below the inscription, water cascaded from the mouth of a bearded, mythical figure into an unadorned, semi-circular basin. In the basin, four fish splayed out from the bottom of the figure’s beard spouted water upward. It was a pedestrian solution. The proportions were simple, the forms basic, and the decorative elements were of the stock, generic type that an architect of far lesser imagination might order straight out of a catalog. Proctor, Marshall, and Farragut received the proposal from the Parks Board on June 9 and returned a decision on July 6, written on the engraved stationery of the Century Club, the West 43rd Street private enclave for members of distinction in the arts and letters. Their recommendation was succinct:

Your committee on the fountain, Riverside Drive & 76th st. recommend that the designs be disapproved.

A. Phimister Proctor

Henry Rutgers Marshall

Loyall Farragut15

Apprised of the Art Commission’s decision, Warren and Wetmore returned to the drawing board and developed a proposal that better reflected the immense talent of Whitney Warren. The firm formally submitted their new proposal to the Art Commission on February 1, 1905. Gone were the banalities and simplistic forms that comprised the emotionless first submittal; all of it was replaced by elegant proportions, pictorial symbols, and decorative flourishes that lent a dignified beauty to the fountain. On February 14, two weeks after receiving the proposal, it was approved by the Art Commission. Nearly fifteen years after Robert Ray Hamilton’s untimely death in the Snake River, the fountain in his name could finally be built.

The Beaux-Arts philosophy that Whitney Warren embraced was fully brought to bear in the revised design for the Hamilton Fountain. The plain, semi-circular base was replaced by a gracefully bowed basin finished with an ornately scalloped edge. The simple, four-foot-tall rectangular stile that formed the backdrop of the fountain was now an eleven-foot-tall, elaborately carved amalgamation of references to water, land, and sky that metaphorically told the story of Ray Hamilton’s sad passing.

The river in which Hamilton drowned was depicted by the head of a fish that spouted water into a scalloped seashell and then emptied into the basin below. Just above the fish’s head, centered within the entire tableau, was a crest used by the ancient Hamilton clans in Scotland and Ireland. There were several variations of this crest used over the ages, all of them in the form of a shield, with two common elements utilized in each version: a lion standing on its hind legs, a symbol of determination and courage, and the cinquefoil, a five-petal flower of the rose family. The cinquefoil had several meanings in heraldry, but was often used as a symbol of plenty or prosperity.

Sedge, reeds, and cattails, all commonly found at a river’s edge, provided one of the most intriguing references that Warren employed in his revised proposal. Carved in high relief on either side of the crest, their wispy tendrils enveloped the shield and provided the illusion of pulling it toward the water. Given the circumstances of Ray’s demise—his spurs getting tangled in sedge that led to his drowning—the stonework made a stark, almost literal, reference to his cause of death.

The land and water were set into a rising, scrolled backdrop that echoed the curve of the basin at street level and featured clusters of carved snail shells and seaweed at its ends, framed by five-foot-tall columns that were topped with globe finials. The scrolls rose to a graceful midpoint of the architectural sculpture and provided a mantle for its crowning element. A six-foot-tall eagle sat atop the lower half of the fountain, its wings fully and majestically spread, its talons nestled into a bed of carved oak leaves and acorns. The eagle provided not only a visual denouement to the entire arrangement, but it also captured an irony inherent in the life and death of Robert Ray Hamilton. One could view the eagle, the very symbol of America, as a metaphor for the history and prestige of the Hamilton family, either coming to rest within the bounds of earth or preparing to take flight toward the heavens.

Cut from Tennessee marble and completed in 1906, the nuanced combination of architectural and sculptural elements, the deft use of pictorial and allegorical references, and the balance achieved by Whitney Warren between artistry and functionality—it was, after all, a fountain intended for use by “man and beast”—is sublime. The fountain exists because of the largesse of one man, Robert Ray Hamilton, yet the only reference to him in the entire composition is simple. Shallowly chiseled into the upward face of the basin perimeter, an inscription, barely visible after more than a hundred years of being exposed to the elements, reads:

BEQUEATHED TO THE PEOPLE OF NEW YORK BY ROBERT RAY HAMILTON.

One hundred and fifteen years after the last pieces of the Hamilton Fountain were set in place, the daily routines of the people of New York have been altered by a global health crisis. Bereft of the theater, museums, and movies, we have learned to look anew at the public objects around us—buildings, memorials, and civic art—that we have long taken for granted. For residents of the Upper West Side, the Hamilton Fountain provides an opportunity to both admire an early work of one of the most significant architectural firms of the early twentieth century and to learn about Robert Ray Hamilton, an ill-fated figure of the Gilded Age.

received his MA in History of Design and Curatorial Studies in 2017 and conducts historical architecture and design research for individuals and design-based institutions. He was the head designer for Issue 2 of Objective, and he is the author of a forthcoming book about the Robert Ray Hamilton scandal (The Scandalous Hamiltons) to be published by Citadel Press, an imprint of Kensington Books, in 2022.

Notes

- Supreme Court, General Term-First Department (New York: The Evening Post Job Printing House, 1893), 6.

- “Water for Man and Beast,” New York Times, May 17, 1896.

- Ibid.

- “Let Him Be Forgotten,” New York Times, April 22, 1891.

- Ibid.

- Minutes and Documents of the Board of Commissioners of the Department of Parks for The Year Ending December 31, 1903 (New York: Mail & Express Company, 1904), 186.

- Sarah Bradford Landau, “The Row Houses of New York’s West Side,” Journal of The Society of Architectural Historians 31, no. 1 (1975): 28.

- Clarence True, Riverside Drive (New York: UNZ & Co., 1899).

- Peter Pennoyer et al., The Architecture of Warren and Wetmore (New York and London: W.W. Norton & Company, 2006), 42.

- “New York City Art Commission” The New York Preservation Archive Project, accessed March 1, 2018.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Pennoyer et al., The Architecture of Warren and Wetmore, 39.

- Letter, Alexander Phimister Proctor, Henry Rutgers Marshall, and Loyall Farragut to the New York Art Commission, July 6, 1903, New York City Art Commission Archives, New York, NY.