Interviews & Reviews Issue 5 2021

The Community Archive of Willi Smith: Street Couture

Charlotte von Hardenburgh

Fig. 1 SITE for WilliWear, Willi Smith’s Office, New York, NY, 1982. Courtesy of the Willi Smith Community Archive.

To categorize Willi Smith (February 29, 1948–April 17, 1987) as a fashion designer would be an understatement (Fig. 1). Over a twenty-year period, Smith’s work spanned the mediums of fashion, art, architecture, design, and performance. Though the exhibition was halted due to the pandemic, the designer’s innovation, impact, and influence are now back on display at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum in the first-ever retrospective of Willi Smith, and the first exhibition that the museum has ever dedicated to a Black designer.1 The exhibition, Willi Smith: Street Couture, also fortunately lives in the digital realm of the museum’s website, where Smith’s work proves to be as relevant and revolutionary today as it was when he was alive in the 1980s.

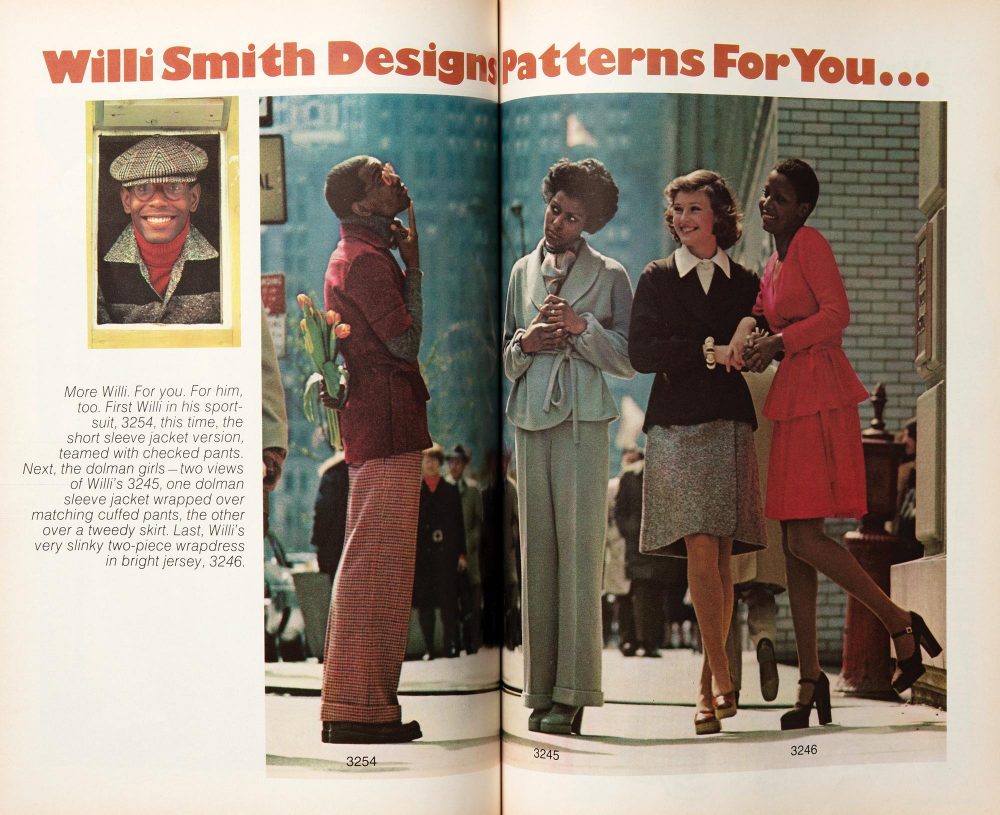

Fig. 2 This Willi Smith for Butterick Patterns 3254, 3245, and 3246, 1973, catalogue editorial presents several of the first patterns that Smith designed, including a menswear pattern that Smith is modeling in the photo. These designs echo Smith’s fall 1973 collection for Digits, which was inspired by Christian Dior’s influential spring 1947 “Corolle” line. This haute couture collection was coined the “New Look” by Harper’s Bazaar editor-in-chief Carmel Snow for reintroducing feminine cinched-waist silhouettes after seasons of somber wartime fashion. Courtesy of the Willi Smith Community Archive.

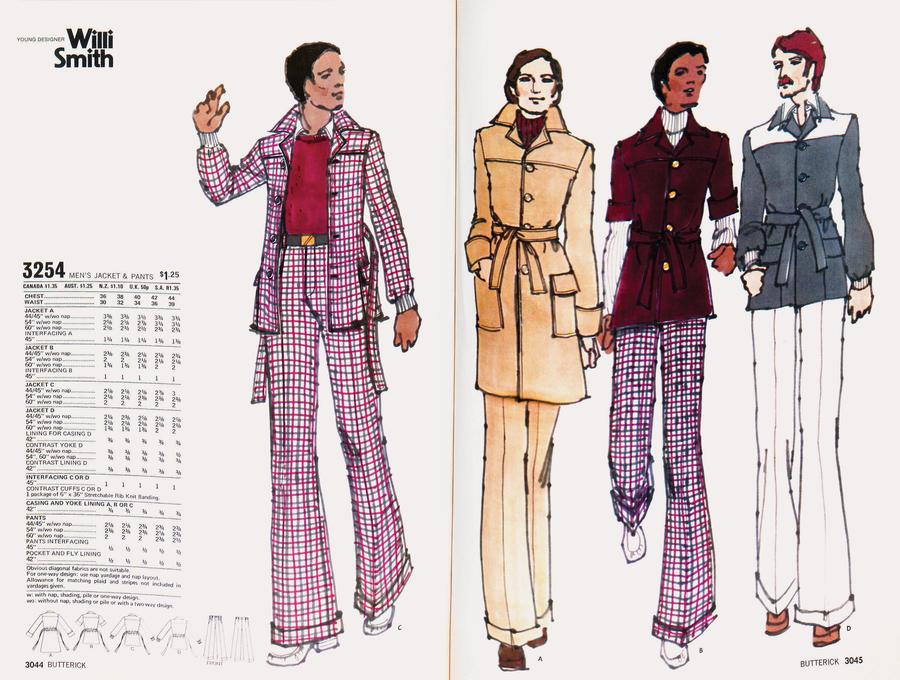

Fig. 3 Willi Smith for Butterick Pattern 3254 from 1973 introduces a menswear set that interprets the Norfolk jacket, a staple of men’s sportswear in England during the second half of the nineteenth century often adapted for military and law-enforcement uniforms. This pattern illustrates an early example of Smith’s interest in uniform dress, a reference he adapted frequently throughout his career. Courtesy of the Willi Smith Community Archive.

Willi Smith—who briefly attended Parsons—had a democratic yet dazzling approach to design. He created affordable and adaptable basics that anyone, regardless of gender or age, could pair with anything and wear anywhere. He cultivated a brand that everyone on the street was wearing, which is why editors started referring to it as streetwear.2 As a fashion designer, Smith wasn’t interested in making clothes for the queen—“but for the people who wave at her as she goes by.”3 He combined laidback oversized silhouettes with pristine tailoring, and he staged theatrical fashion shows at such venues as the Alvin Ailey theater. Although elaborately planned and precisely constructed, his fashion was approachable and accessible. Smith created patterns (Figs. 2 & 3) of his fashions for Butterick and McCall’s so that his designs could reach an even broader audience.4 He made his clothes a conversation between him and his customers stating, “my clothes are canvases for the body that you can dress up or down.”5 In addition, he invited interpretations of his fashions—preferring thrift shoppers who creatively mixed his clothes with other pieces from their closets6—and he was delighted to see his designs mingle amongst other makers à la mode.

To accompany the intended exhibition, Cooper Hewitt assembled a wonderfully extensive Community Archive, consisting of a digital collection of anecdotes and ephemera contributed by close friends, customers, fans, and fashion aficionados of Smith. Cooper Hewitt developed this avant-garde collecting method and prompted the public to contribute to the writing of fashion history.7 This crowdsourced method pioneers a new model of institutional archiving by valuing the lived experience of the public and those close to Smith as the experts of his untold narrative. The Willi Smith Community Archive thus serves as a prime example of how space and history can be claimed to validate the experiences of people whose lives are not typically studied or formally documented. Social and institutional structures tend to propagate a particular white, Western male viewpoint, and history often reflects on the accolades of these men. In contrast, this Community Archive documents and celebrates the work of Willi Smith, who belongs to an historically oppressed8 or marginalized group. It also illustrates how practices of documentation as a canon must be examined and reinterpreted so as to archive the lives and work of those not typically chronicled. Documentary approaches such as the Community Archive offer an alternative and more inclusive means to measure an individual’s cultural impact.

In 1987, Liz Rittersporn, fashion reporter of New York Daily News, called Smith, “the most successful (B)lack designer in fashion history.”9 However, when Alexandra Cunningham Cameron, curator of Contemporary Design at Cooper Hewitt, began organizing the retrospective on Smith, she found a lack of scholarship on his work and influence which, in turn, left a gap in the perception of contemporary fashion and visual culture. Although Smith reached acclaim through earning coveted fashion industry awards and high revenues, his life and work were never seriously studied. Cunningham Cameron notes, that:

(t)elling the story of this charismatic innovator would be necessary to understanding the wider circumstance of design now, and to supplementing a fashion canon that continues to privilege affluent, binary, eurocentric points of view.10

She underscores collaboration as very much in the spirit of Smith’s career and the importance of allowing collaboration to play a significant role in recapturing his career. By inviting “friends, collaborators and admirers to share in writing his history,”11 the archive collects and publishes memories and mementos that contribute to a more robust understanding of Smith’s life, work, charisma, and charm. When developing the platform, Cunningham Cameron aimed to reach a wider audience and to make the content of the exhibition’s publication free and accessible. She states, “(w)e were inspired by projects such as Kim Jenkins’ Fashion and Race Database™, the V&A’s We Want Quant campaign, and various Smithsonian community curation projects.”12 As part of an ongoing initiative to support arts, design and culture, Cargo stepped in to help realize this vision for a new kind of archival experience.13

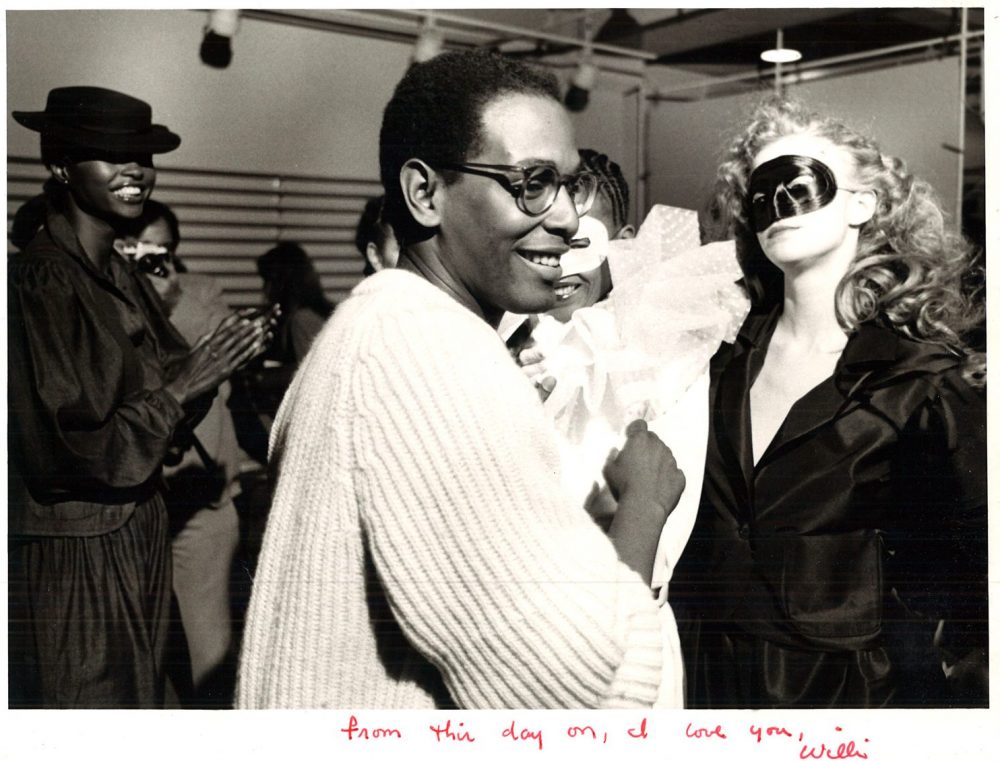

Fig. 4 Willi Smith backstage after the presentation of the WilliWear fall 1978 collection, photographed by Sing Schwartz. This photo was signed by Willi Smith and addressed to Bonnie Brownfield with the inscription: “From this day on, I love you, Willi” Courtesy of the Willi Smith Community Archive.

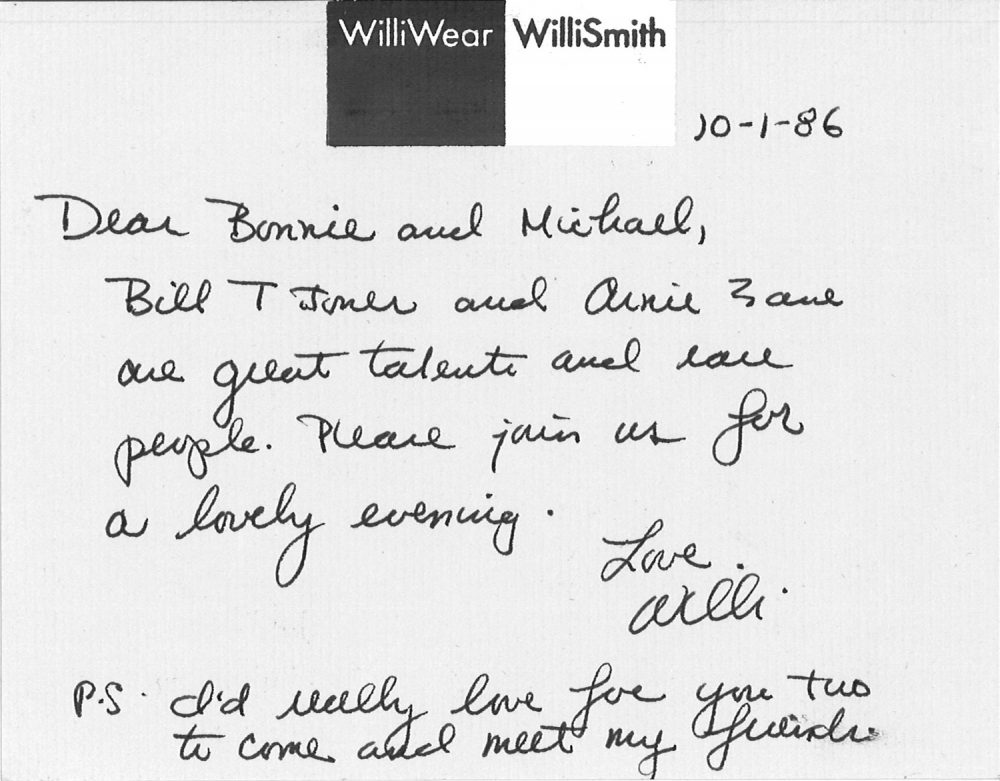

Fig. 5 Invitation from Willi Smith to Bonnie Brownfield to meet Bill T. Jones and Arnie Zane, 1986. Courtesy of the Willi Smith Community Archive.

The Archive features an “About Willi Smith” section which includes biographical information about Smith, and it also provides the curator’s insights into developing the exhibition and assembling the pieces of public memory. Additionally, an interactive digital timeline from 1948–1996 highlights moments of Smith’s life and is supplemented with articles authored by his close friends and colleagues. Five different subcategories—fashion, performance, design, film, and patterns—represent Smith’s diverse and prolific career across a vast array of media to provide a treasure trove of materials. Submissions include candid photographs of the designer moments before a fashion show (Fig. 4), notes penned in Smith’s loopy penmanship (Fig. 5), and documentation of his fans wearing the clothes they made from the patterns he designed. As an example, Cynthia Stubbs-Hill met Smith in 1984 while walking down the street in SoHo and ended up working in both his New York and Paris shops. For the Community Archive, Stubbs-Hill submitted a photo of herself, taken in 2020, wearing a WilliWear suit from 1986.

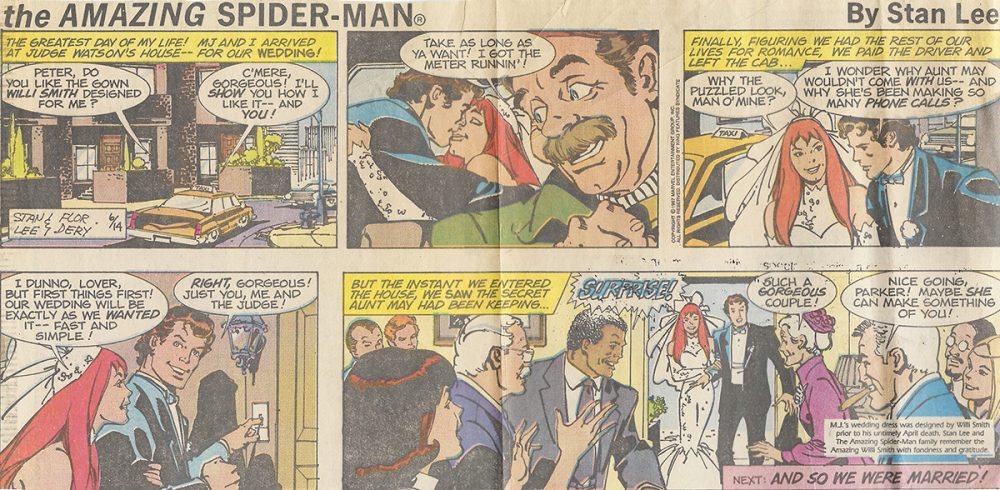

Smith’s various artistic collaborations are also included in the Community Archive. He was friends with the French artists Christo and Jeanne-Claude, and in 1983, when the couple produced Surrounded Islands in Biscayne Bay of Miami, Florida, they asked him to create uniforms for the 430 workers to wear while constructing the piece.14 Smith designed pink long-sleeve t-shirts and white baseball hats with a neck flap. Both pieces were intended to protect workers from the glaring sun and demonstrated Smith’s affinity for mass-produced, practical clothes.15 Another remarkable and unexpected artistic collaboration is found in the pages of Marvel’s comic, The Amazing Spider-Man. In the 1987 “Special Wedding Issue”16, Mary Jane Watson walks down the aisle to marry Peter Parker in a custom Willi Smith bridal gown. (Fig. 6). Smith even has a cameo appearance (Fig. 7) in the special issue of the comic.

Fig. 6 Newspaper clipping from the Philadelphia Inquirer of Peter Parker and Mary Jane Watson’s wedding. An inscription in the bottom right corner reads: “M.J.’s wedding dress was designed by Willi Smith prior to his untimely April death. Stan Lee and The Amazing Spider-man family remember the Amazing Willi Smith with fondness and gratitude.” in black sans serif type. Paul Ryan, “Special Wedding Issue” of The Amazing Spider-Man, 1987. Courtesy of Stacey Appel of the Willi Smith Community Archive.

Fig. 7 Mary Jane Watson visits Willi Smith in his uptown studio. Paul Ryan, “Special Wedding Issue” of The Amazing Spider-Man, 1987. Courtesy of Marvel Comics.

Over thirty years since his death, the exhibition Willi Smith: Street Couture pays tribute to the designer’s boundless creativity and appetite for collaboration. The accompanying Community Archive challenges dominant power structures inherent to institutions like museums where lived experiences are often excluded from traditional archival records. A form of social justice, the Willi Smith Community Archive lends agency to those who wear Smith’s clothing as well as to the designer who envisioned them. Contributors shape the narrative of the acclaimed designer based on what’s hanging in their closets or stowed away in the crevices of their memories. This crowdsourced method of archiving is as innovative as the man whose memory it represents. The exhibition was unfortunately shuttered, but the Community Archive remains a lasting, viable, accessible, and collaborative testament to Willi Smith’s impact as a designer—an opportunity to educate and inspire future generations.17 Fashion is often defined as fleeting, but the Archive of Willi Smith reflects the resilience and perseverance of the designer and the community who continues to love him.

Note from the Editors: As of June 10, 2021, Cooper Hewitt is open to the public and admission is free to view Willi Smith: Street Couture until October 24, 2021. Cooper Hewitt welcomes and encourages contributions in continuing the narrative of Willi Smith. Submit your stories to the Community Archive here.

is a student in the History of Design and Curatorial Studies MA program offered jointly by Parsons School of Design and Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum and also pursuing a graduate certificate in Gender and Sexuality Studies from The New School for Social Research. A fellow in the museum’s Textiles Department, she is currently working on her curatorial capstone for the upcoming exhibition Design, Texture, Color: Dorothy Liebes and the Textiles of the Modern Interior. She is Managing Editor and co-Editor-in-Chief of the fifth issue and first online version of Objective.

Notes

- Caroline Baumann,“Foreword,” Willi Smith: Street Couture (New York: Rizzoli Electa, 2020), 7.

- Bethann Hardison, interviewed by Jonathan Michael Square, 12 July 2019.

- Allison Fiona Duncan, “Willi Smith Glowing Up History,” Cultured Magazine, 12 March 2020.

- Darnell-Jamal Lisby and Luiza Repsold França, “Patterns for You,” Willi Smith Community Archive, 2020.

- Willi Smith and Alexandra Cunningham Cameron, Willi Smith: Street Couture (New York: Rizzoli Electa, 2020), 47.

- Alexandra Cunningham Cameron, “About Willi Smith,” Willi Smith Community Archive, 2020.

- “Willi Smith Community Archive,” Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum, 26 March 2020.

- I use the term “oppressed” to categorize non-male, non-white, non-heterosexual communities.

- Liz Rittersporn, “Designer Willi Smith Dead,” New York Daily News, 19 April 1987.

- Alexandra Cunningham Cameron, “About Willi Smith,” Willi Smith Community Archive, 2020.

- Ibid.

- Alexandra Cunningham Cameron, interviewed by the author, 28 April 2021.

- Cargo is a professional site building platform for designers and artists. Their technological expertise made the Willi Smith Community Archive possible.

- Jarret Earnest, “Willi Smith In Pieces,” Willi Smith Community Archive, 2020.

- Ibid.

- David Michelinie, Jim Shooter, and John Romita Sr., Amazing Spider-Man Annual (1964) #21 (New York: Marvel 1987).

- Alexandra Cunningham Cameron, “About Willi Smith,” Willi Smith Community Archive, 2020.