Design & Activism Issue 5 2021

Disability—Visibility

Marissa Giblin

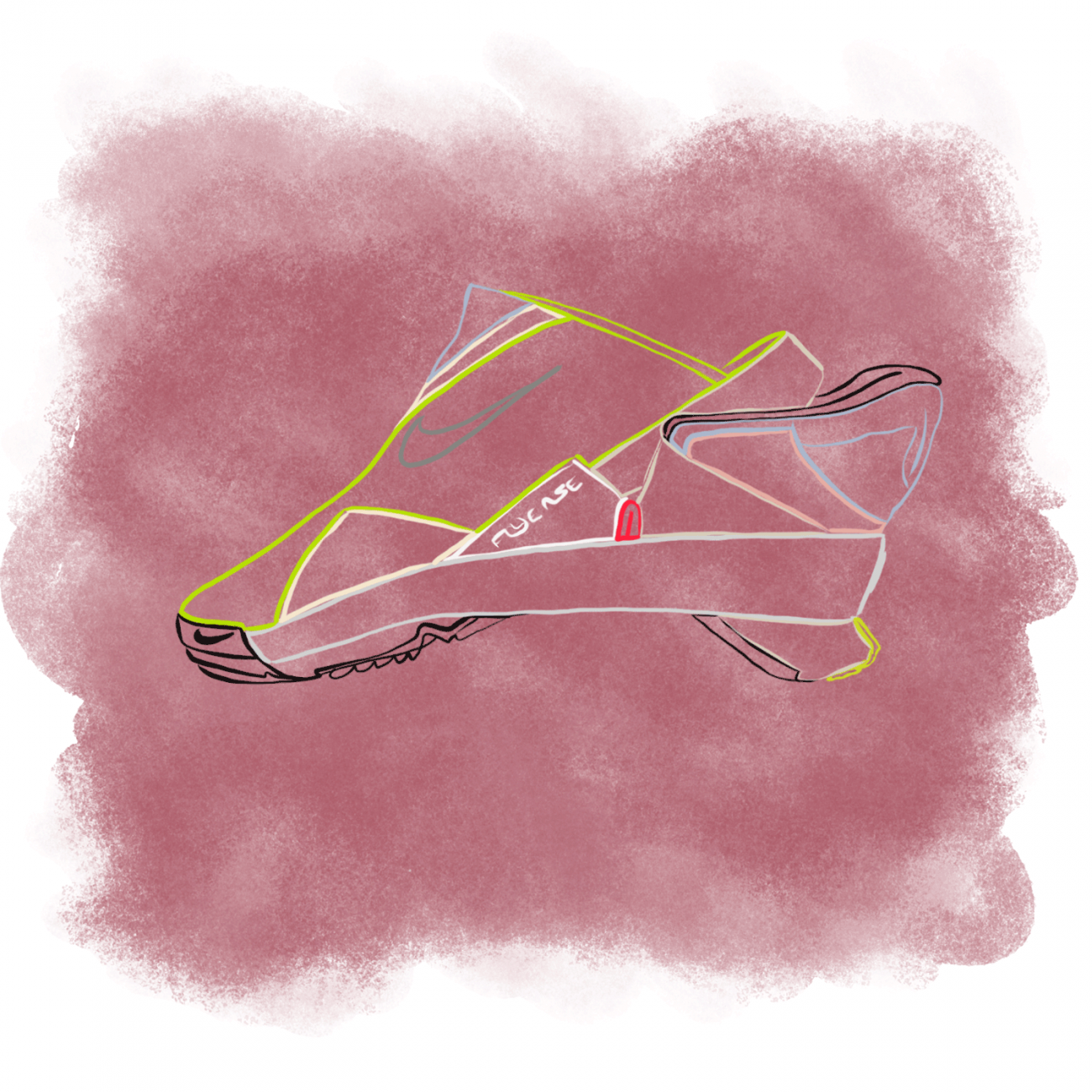

Marissa Giblin, Outline Illustration of Nike’s Go FlyEase Sneaker, New York, NY, 2021. Courtesy of Marissa Giblin.

Nike’s cutting-edge footwear designs and professional athlete partnerships reflect an ethos of innovation and strides towards inclusivity. In March 2021, the brand announced a limited prerelease and later general release of their new Go FlyEase style, a sneaker with adaptive technology that allows the wearer to put the shoe on entirely hands-free. The sneaker is available in three different color palettes: neon and pastel, bold blue and violet, and Nike’s classic monochromatic black. Nike designed the sneaker presumably for the accessible market, meaning that the product uses design practices that make it possible for consumers of all abilities to engage with it. A simple example of this is a pre-peeled orange or pre-cut fruit; while usually priced higher than fresh, uncut produce, it can mean that someone does not have to forgo nutrition simply because of ability. However, by forgoing the use of the word “disabled” or “disability” in their marketing campaign for the Go FlyEase, Nike erases consumers with diverse abilities and instead opens a door to insensitive, ableist comments. Because the shoes were not shown on disabled models, for example, some Twitter users were quick to label those who want to wear the shoes as lazy, questioning if the pandemic is to blame and ignoring disabilities that would make it difficult to bend down and tie a shoe.

Various elements of the Go FlyEase shoe’s technology set the innovative footwear apart from other sneakers in the space. Bending at both the sole and midsole, the rubber-band-like tensioner feature across the heel naturally creates tension across the shoe, allowing the wearer to walk into the shoe and alleviating the need to bend over to put it on. Nike engineers made accessibility a priority. The Go FlyEase, therefore, has the potential to help people who both struggle to put on and tie shoes themselves. When presenting the footwear in a “Behind the Design” video, Nike utilized models with visible disabilities (one woman with a prosthetic arm and another woman who is an amputee of her hand) and two models without visible disabilities. While this choice of models may work to emphasize the reality that not all disabilities are visible, the lack of a distinct reference to disability in Nike’s Go FlyEase item description may draw a line between the disabled consumer and those consumers without disabilities.

With prices starting at $120 USD, the Go FlyEase is not necessarily a budget-friendly shoe. For those on Supplemental Security Income (SSI), receiving Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) payments, or undergoing other financial hardships, it may be impossible or uncomfortable to spend such a large amount on a high-end athletic shoe, even if it might make a significant difference in their quality of life. Additionally, those on SSDI are prohibited from saving more than $2,000 without the risk of losing their benefits. Compounding potential financial strain, disabilities present in a wide range of characteristics, including the potential for two differently sized feet. With such a disability, consumers would potentially need to purchase two pairs of the Go FlyEase, further increasing their cost.

Nike’s Go FlyEase is not the first shoe the company has created for the disabled market; however, this particular item reaches a broader audience than usual, such as pregnant people or busy parents with their hands full. In an article highlighting amputee fashion models, Viktoria Modesta and Aimee Mullins discuss working with designers to create prosthetics. “We cannot help but be reminded of a prosthetic leg that was designed, a few years ago, by Colin Matsco for the sportswear giant Nike and featured the brand’s recognizable swoosh logo on the knee and calf, effectively branding the wearer’s body and turning it into a Nike item.”1 Mullins and Modesta suggest that certain parts of the body do not wear fashion—they become fashion and also a form of corporate promotion. This ambiguity can be seen in the marketing of the Go FlyEase.

Released in February 2021, the now-viral GIF of a model walking in and out of the shoes on a plush plum carpet could have easily portrayed accessibility by using a model who walks with a cane or other mobility aid or a person with at least one prosthetic leg. While not all disabilities are visible, the general public tends to forget that. People with conditions such as fibromyalgia, arthritis, Multiple Sclerosis, or other chronic pain or mobility disabilities might not always appear to be disabled yet would greatly benefit from this shoe. Using a seemingly abled-bodied model to demonstrate the sneakers erases the disabled market—the very people for whom the Go FlyEase was created. The Go FlyEase presents a solution to the problematic relationship between the disabled consumer and footwear. However, Nike’s promotional campaign is fraught with issues, inhibiting the mission from truly coming to fruition. While the Go FlyEase is a significant step forward in seeing large corporations respond to and serve the disabled market, more needs to be done to make the wider consumer market aware of the need for these products and give greater visibility to the large demographic they serve.

is a student in the History of Design and Curatorial Studies MA program offered jointly by Parsons School of Design and Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. She is a co-founder of The New School’s Diverse Abilities Coalition, a new organization for students with disabilities, and serves as its vice president. Her areas of interest include photography, textiles, architecture, and interior design.

Notes

- Laini Burton and Jana Melkumova-Reynolds. “‘My Leg Is a Giant Stiletto Heel’: Fashioning the Prosthetised Body.” Fashion Theory 23, no. 2 (2019): 195–218.