Issue 5 2021 Long Essays

Why Have There Been No Great Women Monuments?

Andrea Lacalamita

Fig. 1 Simone Leigh, Brick House, 2019. A High Line Plinth commission. On view June 2019–Spring 2021. Photo by Timothy Schenck. Courtesy the High Line.

On a spring day in 2019, Simone Leigh’s Brick House (Fig. 1) was lifted by crane onto the High Line, an elevated park which runs along New York City’s West Side, to be installed as the inaugural work for the High Line Plinth public art program. Like many of Leigh’s works, its form conflates the figure of a Black woman with various architectural and symbolic elements related to the history and experience of Black women in the United States.1 Now installed, the sixteen-foot-tall bronze figure towers above 10th Avenue, her powerful silhouette dominating the skyline.

One year later and several blocks uptown, Meredith Bergmann’s Women’s Rights Pioneers Monument (Fig. 2) was installed in Central Park. In contrast to Brick House, the statue was carved in a traditional, realistic style, and unlike the park’s existing statues of fictional and mythological women—including Alice in Wonderland (1959), Juliet of Romeo and Juliet (1977), and Mother Goose (1938)—Bergmann’s statue depicts three historic American women’s rights activists: Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Sojourner Truth. It is the first statue of historic women to be installed in the park and the sixth statue of historical women to be erected in all of New York City.2

Fig. 2 Meredith Bergmann, Women’s Rights Pioneers Monument, 2020. Installed in New York City’s Central Park. Image credit: NYC Parks/Daniel Avila.

Despite their stylistic differences, Brick House and Women’s Rights Pioneers share an important bond: they represent a growing demand for the increased representation of women—specifically, Black women—in the American public sphere. As such, these two statues participate in the United States’ long history of “female image-building,” the development of which is deeply tied to the history of women’s suffrage and to the ever-changing public perceptions of women’s place in American society.3 Like their predecessors, the artists of these two contemporary monuments have grappled with questions of representation—of not only who to memorialize but how. Unique to female image-building in the US during the twenty-first century, however, is the consideration of race and gender identity as major factors in achieving equal representation for women in the public realm.

Brick House and Women’s Rights Pioneers both embody and respond to contemporary American values, while also aligning with historic patterns of female image-building. An analysis of these two monuments and their place within the history of American monument-building reveals the challenges artists and advocates of women’s monuments face today as they address issues of race, representation, and gender in the public domain.

Of the approximately 5,193 public outdoor statues depicting historical figures in the United States, only 394 (less than eight percent) are of women.4 The US Capitol’s National Statuary Hall Collection reflects these statistics on a microcosmic scale: before the year 2000, only six of the Hall’s 100 statues were of women.5 Erika Doss, professor of American Studies at the University of Notre Dame and author of Memorial Mania (2010), attributes this disproportionate number of male statues to the fact that American history is male-centred.6 To complicate matters, while many of these male heroes are commemorated with statues that represent their individual historic achievements, existing public statues of women—especially those erected between 1860 and 1959—tend to be mythological or allegorical in nature.7 This has significantly reduced the public visibility of women’s individual contributions to American history.

Statistics regarding the representation of Black women (and men) in the American public sphere are even more dismal. Only recently, in 2018, did the Florida House and Senate vote to introduce the first state-commissioned statue of a Black American—civil rights educator and activist Mary McLeod Bethune—into the Statuary Hall Collection.8 And while there are currently ten monuments and memorials to Black individuals in New York City’s parks, only two of these—Swing Low: Harriet Tubman Memorial (Saar, 2008) in Harlem and the Women’s Rights Pioneers Monument (Bergmann, 2020) in Central Park—represent historic Black women.9 Compounding these numbers is the fact that of all the permanent, public sculptures installed throughout New York City, only four were created by Black women artists.10

But there is a growing collective desire within the United States to correct the public record. This involves both the building of new monuments and the removal of old ones. Following the death of George Floyd in May 2020, over 130 Confederate statues in over three dozen states were removed or relocated from their original sites, either by government decree or acts of public vandalism.11 Though Confederate statues have long been a source of debate in the United States, these most recent actions indicate a clear shift in national spirit; their removal marks a decisive moment in the United States’ collective reckoning with its racist and patriarchal past. In many cases, their removal has left space for the construction of new monuments to women. In 2020, Virginia voted to remove its statue of Confederate General Robert E. Lee from the US Capitol and to replace it with a monument to civil rights leader Barbara Johns.12

Brick House and Women’s Rights Pioneers are two recent additions to the monumental landscape in the United States that address the vast underrepresentation of Black women head-on. However, there exists an important difference between the two statues. From its inception, Leigh’s design for Brick House demonstrated equal concern for the visual expression of both race and gender, whereas Bergmann’s original design for Women’s Rights Pioneers clearly prioritized the expression of gender over race. Though this distinction between the two artists’ approaches may seem subtle, it represents a vast difference between each statue’s final design. Whereas the finished form of Brick House reflects the artist’s original intent, the final composition for Women’s Rights Pioneers resulted from major revisions to its original form, made in response to public outcry about its failure to consider race as an integral part of its design.

Controversy surrounding Women’s Rights Pioneers erupted following the unveiling of a maquette of the proposed statue in July 2018. The maquette depicted two historic women, Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, holding a scrolling list that would contain the names of twenty-two other women who contributed to the women’s suffrage movement—seven of whom were African American. The design had been developed by Bergmann in close consultation with the New York City Parks Department and the advocacy group Statue Fund (since renamed to Monumental Women), who had raised private funds for the statue’s design and construction. The Statue Fund had also developed the design brief for the project, requesting proposals for “statues of Anthony and Stanton that would allude to the work of others.”13

Though a statue of Anthony and Stanton would have accomplished the Statue Fund’s goal of erecting the first statue of historic women in Central Park, critics reacted poorly to Bergmann’s original design for its failure to include Black women figures. Traditionally, the story of women’s suffrage has been told through the lens of White, middle-class women (with Anthony and Stanton as their iconic leaders), but recent scholarly efforts, such as the National Portrait Gallery’s exhibition Votes for Women: A Portrait of Persistence (March 29, 2019–January 5, 2020), have begun to unearth the role of African-American women in this history.14

In a scathing New York Times article titled “Is a Planned Monument to Women’s Rights Racist?,” reporter Ginia Bellafante noted that Bergmann’s design made it look as if Anthony and Stanton were “writing the history of suffrage”—an issue she believed to be especially problematic given the fact that Anthony and Stanton were both known to hold racial prejudices and already had “ownership of a narrative that erased the participation of (B)lack women in the movement.”15 These observations echoed the sentiments of feminist icon Gloria Steinem, who is quoted in the same article as saying she did not believe it was appropriate to have “a statue of two (W)hite women representing the vote for all women.” For Steinem and Bellafante, the decision to include Black women by name only, rather than representing them as real historic figures, was an affront to contemporary feminism and a missed opportunity to represent more women of color in the American public sphere. They were not alone in this opinion.16

Bellafante described the women behind the Statue Fund as “(W)hite, well-intentioned feminists of a certain vintage” who clearly struggled to understand the public criticism levelled at the proposed statue.17 Pam Elam, the fund’s president, told Bellafante that although the group was “committed to inclusion…you can’t ask one statue to meet all the desires of the people who have waited so long for recognition.” The American public disagreed. Despite resistance from both the Statue Fund and the Parks Department, who told Bellafante that any major revisions to the statue “would compromise the artist’s vision,” it was announced in August 2019 that Women’s Rights Pioneers would be revised to include the figure of Sojourner Truth, a Black woman’s rights activist who had worked alongside Anthony and Stanton.18

Fig. 3 Charles Grafly, Pioneer Mother, 1915. Installed at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco. Image credit: Creative Commons.

Elam’s particular brand of feminism, one which champions the inclusion of women in the public sphere while simultaneously (if unintentionally) promoting a very narrow view of diversity, recalls an earlier era. As Lindsay Erin Shannon describes in her doctoral thesis, “Monuments to the ‘New Woman’: Public Art and Female Image Building in America, 1876–1940,” the image of the Western woman has historically been “stereotyped as a narrow segment of the population…ignoring the experiences of women who were immigrants, African American, Hispanic, Asian, Native American, domestic servants, and wage earners.”19 The monument Pioneer Mother (1914) (Fig. 3), designed by sculptor Charles Grafly (1862–1929) and exhibited at the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition (PPIE), exemplifies this convention. While Pioneer Mother was considered progressive for contributing to the increased visual presence of women at the fair, it is problematic for contributing to a visual tradition that portrayed White women as the civilizers of the West.

Fig. 4 Adelaide Johnson, Portrait Monument to Lucretia Mott, Elizabeth Cady and Susan B. Anthony, 1920. Installed in the Capitol crypt, Washington, DC. Image credit: Architect of the Capitol, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [LC-USA7-27850 DLC].

In 1920, a monument titled Portrait Monument to Lucretia Mott, Elizabeth Cady and Susan B. Anthony by Adelaide Johnson was installed in the US Capitol Rotunda (Fig. 4). Like Bergmann’s original design for Women’s Rights Pioneers, Johnson’s statue presented a distinctly whitewashed version of the American women’s suffrage movement. In contrast to Bergmann’s design, Johnson’s statue was controversial for simply having inserted women into a political, public space.20 With time, however, public feeling surrounding the Portrait Monument began to change in ways that anticipated the Women’s Rights Pioneers controversy. In 2005, a bill was introduced to Congress by a coalition of lobbyists led by C. DeLores Tucker, co-founder of the National Congress of Black Women, who had led a decades-long campaign to alter Johnson’s original Portrait Monument to include a bust of Sojourner Truth. Though the bill was not approved, a new bill was passed two years later which permitted a separate portrait bust of Truth to be displayed in the Capitol. Installed in 2009, Sojourner Truth was the first statue in the Capitol building to honor a Black woman.21

The history of Johnson’s Portrait Monument sheds light on a recent and crucial shift in public attitude toward monument-building in America. It is no longer sufficient for monuments to represent a single minority group, like women. Rather, the American public of the twenty-first century demands that new monuments be held accountable for diversity in all its forms. In New York City, a new $10 million public arts campaign titled “She Built NYC” makes this contemporary shift clear. Of the seven historic women to be honoured with a statue, six belong to BIPOC and/or queer communities.22

Beyond the question of who new monuments to women should commemorate is the issue of how monumental women should be represented. Kirk Savage, author of Monument Wars: Washington, D.C., the National Mall, and the Transformation of the Memorial Landscape (2009), notes that artists, lacking much precedent for representing women in public statuary, have taken decades to understand “how to represent female achievement in this traditionally male art form.”23 Perhaps for this reason, monuments to women have historically alternated between conventional and innovative forms—a trend which, as Shannon notes, reveals not only an evolution of gender boundaries and the conception of womanhood throughout American history, but also changing social and artistic norms.24 For over a hundred years, building monuments to women has required artists and advocates to balance public taste and national ideals with their own desire to push the medium—and with it the perception of women’s role in society—forward. In this way, the specific methods of visual representation employed by artists and designers of monuments to women are critical to understanding these statues’ social meaning and impact.

Brick House and Women’s Rights Pioneers represent two distinct contemporary approaches to the representation of the monumental female form, each of which presents its own unique advantages and challenges. Whereas Leigh’s Brick House is made in a somewhat abstract, albeit figurative, style, Bergmann’s Women’s Rights Pioneers is carved in the real likeness of historic women. Bergmann, however, was restricted in style by the New York City Parks Department, which “would not allow an overtly modern or conceptual artwork.”25 In hindsight, this decision perhaps contributed to the statue’s controversy; as Bellafante noted in her critique of Women’s Rights Pioneers, “a conceptual piece might have made clearer how large and diverse the suffrage movement was.”26 Yet, the department’s conservative approach was possibly tied to a belief that a more realistic or traditional representation of these pioneering women would best achieve the Statue Fund’s goal of bringing the first statue of historic women to Central Park.

The practice of memorializing historic women in a realistic style recalls early monuments to women in America, built as the women’s suffrage movement advanced throughout the first two decades of the twentieth century. Though they were some of the first statues of historic women in the country, artists of these monuments did not invent a new public art form with which to represent women. Rather, they adopted the well-established form of male “hero statues”—a statuary style in the European tradition featuring single-figure bronze and marble statues mounted atop pedestals. As Shannon notes, these new “heroine statues” not only embodied values of female patriotism, civic duty, and progressive views on contemporary women’s citizenship, but they also helped to establish the presence of American women in the historical record as equivalent to men.27 In many ways, Women’s Rights Pioneers accomplishes the same.

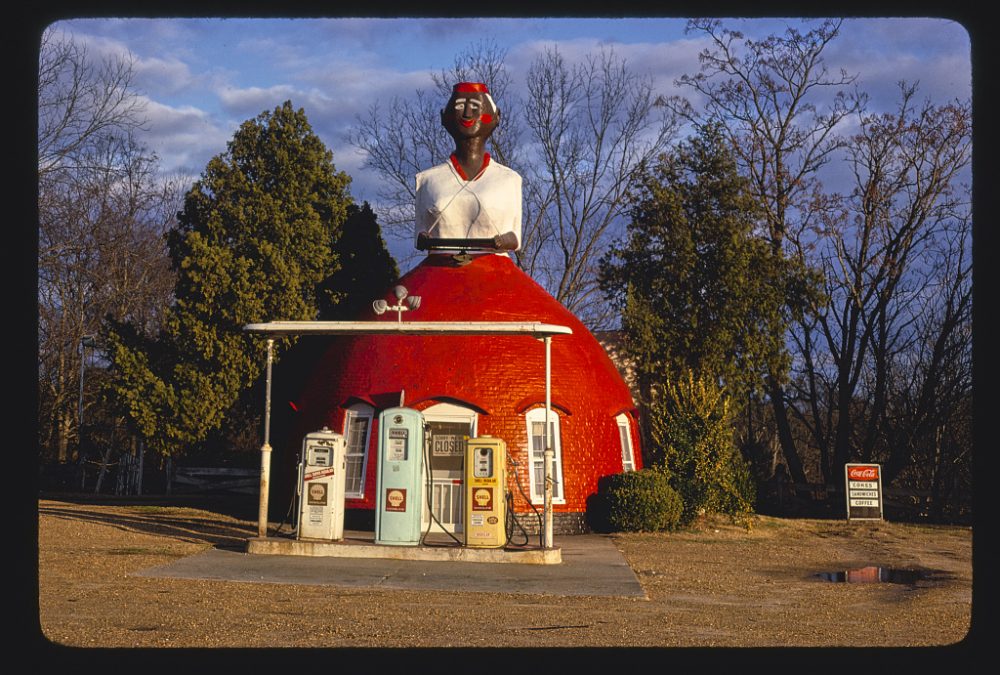

Fig. 5 Mammy’s Cupboard, angle view, 1979. Route 61, Natchez, Mississippi. Image credit: John Margolies Roadside America photograph archive (1972-2008), Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [LC-MA05-92].

Leigh’s Brick House, however, stands in contrast to these realistic statues. Allegorical and larger-than-life, Brick House is not a representation of a specific historic individual, but rather an idealized figure of a Black woman, whose skirt-like torso also resembles a clay house. Its architectural form draws inspiration from two distinct sources: the dome-shaped dwellings (teleuks) of the Mousgoum in West Africa and a restaurant called Mammy’s Cupboard, built in 1940 in Natchez, Mississippi (Fig. 5). By referencing these elements, Leigh reclaims imagery that has historically been associated with degrading African-American stereotypes, such as the “primitive hut” or the “Black woman domestic worker.”28 Rich with meaning and complex in form, Brick House is a powerful monument to the shared history of Black women in America. Its strength lies in the fact that it is both specific and anonymous; it does not represent one Black woman but all Black women. Herein lies the critical difference between monuments that employ abstract modes of representation and monuments that are more realistic in style: while realistic statues are well-suited to the celebration of women’s individual accomplishments and perhaps more easily understood or read by the viewer, they are often less capable of producing a more inclusive or expansive form of expression.

Fig. 6 Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, DAR monument, 1929. Washington, DC.

However, it is important to note that abstract representations of women also have their disadvantages. Though they do contribute to an increased presence of women in the public sphere, they also render the women they represent both nameless and faceless, an unfortunate situation given the lack of monuments built to honor historically important women in the United States. This issue presents itself in monuments to women that became popular during World War I, which used idealized or anonymous female figures to illustrate a historic narrative and reflect national values. In contrast to earlier “heroic” statues, such monuments as Frances Rich’s Army-Navy Nurses Monument (1938) at Arlington National Cemetery and Gertrude Vanderbilt’s DAR Monument (1929) in Washington DC (Fig. 6) captured and mythologized the collective spirit of women’s contributions to American history, but denied women recognition for their individual achievements.29

It is clear, then, that both Brick House and Women’s Rights Pioneers succeed in making their own distinct contributions to the history of American monument-building. Women’s Rights Pioneers introduces three historic women into the public sphere, while Brick House testifies to the collective experience of Black women and to the emotive power that monuments can achieve. Questions about how to represent women in public spaces are far from resolved, but together these two statues begin to construct a more complete and diverse landscape of contemporary and historical women. As the American public continues to push toward greater and more diverse representations of women, potential lies in pursuing both approaches simultaneously. Instead of restricting monuments to women to one style or medium of expression, it might be most appropriate for America’s twenty-first century monuments to women to find their form in several different typologies at once—in a diversity and plurality of forms reflective of the complex issues of womanhood, gender, class, and race that American women contend with today.

is a licensed architect (MArch, OAA) and received her MA in the History of Design and Curatorial Studies from Parsons School of Design in 2021. Her graduating project was a curatorial capstone with the Product Design and Decorative Arts department at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum for the upcoming exhibition, Hector Guimard: How Paris Got Its Curves.

Notes

- For a brief overview of Leigh’s recent work, see Robin Pogrebin and Hilarie M. Sheets, “An Artist Ascendant: Simone Leigh Moves Into the Mainstream,” New York Times, August 29, 2018.

- Currently, the statues of historical women in New York City include: Joan of Arc Memorial (1915) by Anna Vaughn Hyatt Huntington, Golda Meir (1984) by Beatrice Goldfine, Gertrude Stein (1992) by Jo Davidson, Eleanor Roosevelt Memorial (1996) by Penelope Jencks, Swing Low: Harriet Tubman Memorial (2008) by Alison Saar, and Women’s Rights Pioneers Monument (2020) by Meredith Bergmann.

- See Lindsay Erin Shannon, “Monuments to the ‘New Woman’: Public Art and Female Image Building in America, 1876–1940” (PhD diss., University of Iowa, Fall 2013), 24. Monuments included in Shannon’s study illustrate how “sculptural monuments dedicated to women shaped, and were shaped by, increasing demands for citizenship.”

- Statistics are taken from the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s Art Inventories Catalog, considered the most up-to-date catalogue of such works. As cited in Cari Shane, “Why the dearth of statues honoring women in Statuary Hall and elsewhere?” Washington Post, April 15, 2011.

- In 2000, Congress voted to allow states to replace either, or both, of their statues to allow for the selections to reflect the “change of philosophies of individual states.” Only one state (Alabama) voted to replace an existing statue of a man with one of a woman (a statue of Helen Adams Keller replaced a statue of Jabez Lamar Monroe Curry in 2009). Two other states (North Dakota and Nevada) elected to install new statues of women (Sakakawea and Sarah Winnemucca, respectively), but neither replaced an existing statue. See Shane, “Why the Dearth.”

- Erika Doss as quoted in Shane, “Why the Dearth.”

- Shane, “Why the Dearth.” For a more complete history of women in neoclassical sculpture, see Shannon, “Monuments to the ‘New Woman,’” 39–46.

- Marissa Fessenden, “U.S. Capitol’s Statuary Hall Collection Will Get Its First State-Commissioned Statue of a Black American,” Smithsonian Magazine, March 21, 2018.

- For a more comprehensive overview, see “Monuments and Sculptures of Black Historical Figures in NYC Parks,” NYC Parks, https://www.nycgovparks.org/art-and-antiquities/monuments/black-history-month.

- Meg Whiteford, “The Making of Simone Leigh’s Brick House,” Hauser & Wirth.

- Erik Ortiz, “These Confederate Statues Were Removed. But Where Did They Go?” NBC News, September 20, 2020.

- Bryan Pietsch, “Robert E. Lee Statue is Removed from U.S. Capitol,” New York Times, December 21, 2020.

- As described in Ginia Bellafante, “Is a Planned Monument to Women’s Rights Racist?” New York Times, January 17, 2019.

- See Jennifer Schuessler, “The Complex History of the Women’s Suffrage Movement,” New York Times, August 15, 2019, and National Portrait Gallery, “Votes for Women: A Portrait of Persistence.”

- Bellafante is referring to History of Woman Suffrage, edited by Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, Matilda Joslyn, and Ida Husted Harper, published in six different volumes between 1881 and 1922.

- See also Brent Staples, “A Whitewashed Monument to Women’s Suffrage,” New York Times, May 14, 2019.

- Bellafante, “Is a Planned Monument?”

- This decision has also received its share of criticism. See Zachary Small, “A Monument to Women’s Suffrage Received Unanimous Approval Despite Controversy,” Hyperallergic, March 19, 2019.

- Shannon references the work of Joan M. Jensen and Darlis A. Miller, who investigate “the gentle tamer category [which] encompasses western women as civilizers, ladies, and suffragists.” See Shannon, “Monuments to the ‘New Woman’,” 146–147 and Joan M. Jensen and Darlis A. Miller, “The Gentle Tamer Revisited: New Approaches to the History of Women in the American West,” Pacific Historical Review 49, no. 2 (1980), 179.

- For more on Adelaide Johnson and the controversy surrounding Portrait Monument, see Kimberly A. Hamlin, “Monumental Women: Adelaide Johnson, Sculptor of Suffrage,” Humanities, August 10, 2020.

- Shannon, “Monuments to the ‘New Woman,’” 190–191. Recent scholarship has begun to trace the intersection of race and gender within the history of American sculpture and monument-building. One notable example is Charmaine Nelson, The Color of Stone: Sculpting the Black Female Subject in Nineteenth-Century America (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007), which explores issues of race and color in neoclassical sculpture through a Black feminist art historical lens.

- Statues currently slated for construction include: Rep. Shirley Chisholm (Brooklyn), Billie Holiday (Queens), Elizabeth Jennings Graham (Manhattan), Dr. Helen Rodriguez Trías (Bronx), Katherine Walker (Staten Island), Marsha P. Johnson (Manhattan), and Sylvia Rivera (Manhattan). For more information, see “She Built NYC Honors Seven Trailblazers with Monuments Around City,” She Built NYC.

- Savage as quoted in Shane, “Why the Dearth.”

- Shannon, “Monuments to the ‘New Woman,’” 182–3.

- Bellafante, “Is a Planned Monument?”

- Bellafante, “Is a Planned Monument?”

- Perhaps one of the most well-known statues of this variety is New York City’s Joan of Arc (1915) by Anna Hyatt Huntington, the first equestrian monument made by a woman in the United States. According to Shannon, “this established monument style communicated familiar narratives of active civic engagement which did not provoke controversy, and they could then be bent to new interpretations relating to the women’s movement and popular understanding of female citizenship more generally.” See Shannon, “Monuments to the ‘New Woman,’” 110–118 and 130–131.

- In “The Making of,” Whiteford describes Mammy’s Cupboard in greater detail: “Built in 1940, Mammy’s Cupboard is a restaurant in Natchez, Mississippi. The brick restaurant is shaped like a 28-foot-tall woman wearing a round skirt that towers alongside US Highway 61. Mammy’s Cupboard originally took the guise of a darker-skinned Mammy figure, the racist archetype of a Black woman domestic worker that was prevalent in the late 19th to early 20th centuries and which was popularized in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin and later with the character of Mammy in the film Gone with the Wind.” See Whiteford, “The Making of.” In Pogrebin and Sheets, “An Artist Ascendant,” Leigh notes that the primitive hut “has been used to humiliate us for years and years.” It is interesting to note here a possible connection with the racist imagery of the post-Reconstruction United States, a time during which (according to Shannon) “racism made depictions of the African American female body fraught with potential for caricature and misinterpretation by both white artists and audiences” and “characterized African American women as domestic or factory workers.” See also Shannon, “Monuments to the ‘New Woman,’” 129.

- See Shannon, “Chapter IV: The Body Politic: Representing Women’s Collective Work” in “Monuments to the ‘New Woman,’” 133–179.