Issue 5 2021 Long Essays

Pressbook Advertising in 1950: The Jackie Robinson Story

Alexis Fair

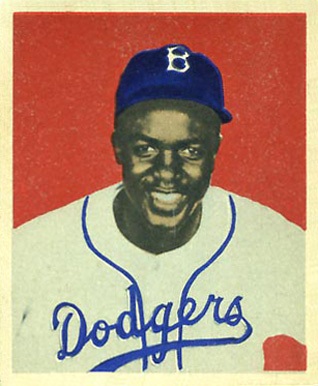

Jackie Robinson 1949 Baseball Card, Bowman #50, Courtesy of Ross Uitts of OldSportsCards.com

In a 1937 lecture the studio executive and film producer David O. Selznick discussed film as most studio executives would have done during the “Golden Age” of Hollywood—like a businessman.1 He asserted that it was necessary for a producer to not only know the creative ends of the business, but also the other ends, “distribution, exhibition…commercial” if one “is to make more than one picture.”2 This statement implies that the creative side of filmmaking cannot exist without the business side; the film industry only flourishes because of both. This paper looks at the commercial side of the film industry, and, more specifically, at a type of promotional aid published by Hollywood film studios, the pressbook, for what it tells us about racial conflict in post-World War II America.

The pressbook was an essential magazine-like promotional publication. According to film studies scholar Mark S. Miller:

the booklet contained the company’s suggested words and graphics for use in promoting the film to a variety of potential audiences. Among the major motion picture companies, pressbooks’ contents were fairly standardized by the late 1930s. They served as catalogues of ‘promotional strategies’ (in the sense of techniques to help sell a commodity).3

Pressbooks were also known as exhibitor’s campaign books or showman’s manuals. They were typically broken down into four sections: publicity,4 advertising,5 exploitation, and accessories. As described by Miller:

The publicity pages offered ‘articles’, which were to be planted in newspapers by an exhibitor including canned reviews, star biographies and descriptive backgrounds, and behind-the-scenes production anecdotes. The advertising section carried differently-sized advertising mats that were to be purchased from the company for use in newspapers, and sometimes copy to be read for radio ads. The exploitation pages contained suggestions for promotional strategies, including merchandizing tie-ins and stunts that might call attention to the film or theatre. Accessories included items for sale or rent from the company, including trailers, publicity stills, lobby cards and various sizes of posters.6

Given these various materials, a pressbook was not only useful as a resource for movie theater owners in the past but also for cultural historians today for what they have to say about historical context. The Eagle Lion Films’ pressbook for the film The Jackie Robinson Story (1950), for example, illustrates how film advertising techniques promoted an idealized public view of America during the Cold War. The advertising in the pressbook did not necessarily reflect what was truly happening then in America in terms of desegregation, even if the film—and Jackie Robinson’s life—was all about that.

Opposition to racist ideologies in the United States was necessary to change the international view of post-World War II America and capitalism in the Cold War with the USSR and Communism. Sociologist Doug McAdam writes about the end of American Isolationism:7

If electoral realignments of the New Deal era served to enhance the political importance of blacks, the Second World War continued this trend. It did so by effectively terminating the isolationist foreign policy that had long defined America’s relationship to the rest of the world. As a result, national political leaders found themselves exposed, in the postwar era, to international political pressures…Locked in an intense ideological struggle with the USSR for influence among the emerging third-world nations, American racism suddenly took on international significance as an effective propaganda weapon of the Communists.8

In 1948 Truman had desegregated the armed forces, and in December 1952 the United States Attorney General filed a brief stating: “It is in the context of the present world struggle between freedom and tyranny that the problem of racial discrimination must be viewed…Racial discrimination furnishes grist for the Communist propaganda mills, and raises doubt even among friendly nations as to the intensity of our devotion to the democratic faith.”9 In his book Political process and the development of Black insurgency, 1930-1970—2nd Edition, McAdam provides a graph which shows a peak from 1946 to 1950 in “the number of Supreme Court civil rights cases and the proportion of those cases decided in the favor of black litigants”.10 The number of pro-civil rights measures introduced in the United States Senate from 1949 to 1950 also increased. Even if many of these measures weren’t passed by the Senate, the sheer number introduced reflected the awareness and “emergence of important conflicts”11 Historian Mary L. Dudziak likewise asserts that despite opposition to pro-civil rights measures, the United States found it important to “disseminate favorable information about the United States to other countries.”12 She wrote:

the Roosevelt administration increasingly recognized the value of print and broadcast media in the U.S. government efforts to influence international opinion. By 1948, the Cold War increased the perceived importance of such efforts. In some government circles fears were expressed that America was losing an unequal war of propaganda in which the Soviet Union and its satellites routinely misrepresented and distorted American ideals and actions. The federal government needed to respond by disseminating the ‘truth’ to counteract such communist propaganda13

Drawing, Design for Gymnasium, Baseball Batter, after 1934; Designed by William Hunt Diederich (American, b. Hungary, 1884–1953); USA; graphite on tracing paper; 16 x 13.5 cm (6 5/16 x 5 5/16 in.); Gift of Diana Diederich Blake; 1992-92-64, Courtesy of Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum.

The film industry was an easy way to disseminate the ‘truth’ or a positive image of America. The film The Jackie Robinson Story released in 1950, demonstrates this. While the film itself documents Jackie Robinson’s struggle for equality in baseball and his ultimate success in desegregating the sport, the advertisements for the film in the pressbook present his story somewhat differently. Robinson, who played himself in the movie, is portrayed as an American hero, a pacifist, and a success due to his opportunities in the US. The pressbook portrayal serves the American national interest by illustrating a positive image to the world in terms of race relations. However, closer examination reveals an ambiguity about civil rights activism in mid-century America.

At first the pressbook presents Robinson as they would any American star or hero. His name is large, and his image iconic, just as other Hollywood star images would have appeared in other pressbooks. The fact that Robinson played himself in the film enhanced the authenticity of the film, and it also gave the film studio a chance to monopolize on his celebrity. There were merchandising tie-ins to Chesterfield cigarettes, Wheaties cereal, and other products such as comic books, flip books, and even a song all about Robinson.14 Other Robinson-themed products that appeared in the pressbook included a doll, objects for the home desk, and clothing.15

One newspaper journalist asserted that the film’s release was crucial because it was necessary to celebrate Robinson’s moment of glory at the time and to depict desegregation as a highly contested issue.16 However, the pressbook advertisements did not feature any content about the civil rights movement or racism. In fact, the advertisements in the “Advertising” section of the pressbook are problematic in how they contrast with the oppressive society in which African Americans lived. All difficult subject matter is essentially glossed over in the one, two, and three column advertisements.17 In one of the pressbook advertisements Robinson’s image is “branded” by the words “Made in the U.S.A.” in block lettering.18 This makes Robinson look as though he is a “product” of the United States and that his American image is “for sale.” Essentially it is for sale in these pressbook advertisements. A movie theater owner could pay to rent some of the advertising material shown in the pressbooks such as posters and lobby cards, and/or the owner could choose to use the print advertisements illustrated in the pressbook in local magazines and newspapers.

One such advertisement read that the film has “THE DRAMA OF A MAN WHO FOUGHT THE AMERICAN WAY—…with a ball…a bat…and a glove!”19 The “American Way” implicitly is the peaceful way. As a result, Jackie Robinson might come across as a somewhat passive figure in civil rights history. The studio was sure to emphasize a line from the film where sports executive Wesley Branch Rickey says to Robinson, “‘They’ll shout insults at you…they’ll come in to you spikes first…they’ll throw at your head…but no matter what happens—remember—you can’t fight back!’”20 [emphasis by original author] This quote appears several times in the pressbook advertisements, along with one about fighting only via baseball. Such copy is especially significant because it was most likely placed in a magazine or newspaper, and these were more accessible forms of advertising than a lobby card or poster which would mainly be found at a movie theater—a place where African Americans were often not allowed to enter. While the pressbook’s content showing Robinson as an all-American hero with equal rights to play baseball is “democratic” enough to project a positive national image to the world, the specific language of the advertisements may have actually encouraged the suppression of civil rights conflict in America. Taglines communicate that African Americans should “fight for their rights” passively rather than engaging in “disruptive” behavior. Even if this was not the intent of the movie studio, the advertising may implicitly disseminate this message.

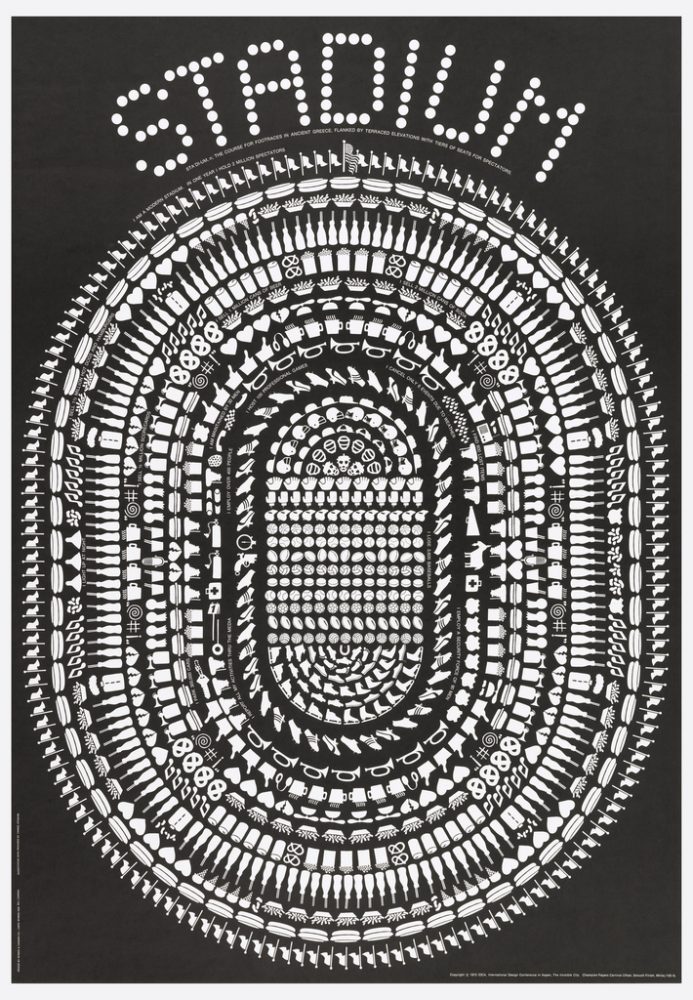

Poster, Stadium, 1972; USA; offset lithograph on paper; 67.6 x 60.9 cm (26 5/8 x 24 in.); Gift of Unknown Donor; 1980-32-1260, Courtesy of Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum.

The pressbook appears to blend advertisements that pay homage to Robinson’s success in America with advertising that suggests to African Americans that they should remain quiet in the face of white supremacism and discrimination. In reality, Robinson was a fiercely competitive athlete and not a pacifist. In a 2013 online article published by Psychology Today the author praised Robinson’s enormous restraint in the face of angry crowds, achieved at the time through a kind of “mindfulness training.”21 While the article may have been written with the intention to celebrate Robinson, it unfortunately contributes to a mythology surrounding him. The image of Robinson as pacifist is misguided because he only practiced pacifism for a short period of time, which was when he was working to break the baseball color line. For many more years he actively and loudly participated in civil rights activism.22 In fact, his passive activism caused him health problems.23 In his autobiography he wrote that since he was eight years old and experienced being called a racial slur from a neighborhood girl, he “believed in payback, retaliation. The most luxurious possession, the richest treasure anybody has, is his personal dignity.”24 His record of activism proves he was certainly not a pacifist. In 1944, before he broke the color line in baseball, he was court martialed for not moving to the back of an Army bus. He famously attended the March on Washington, among many other civil rights rallies, was a board member of the NAACP, and a co-founder of the Freedom National Bank in Harlem, the first interracial bank in New York. 25

More recently, in 2013, the movie 42 retells Jackie Robinson’s story with Chadwick Boseman playing the ballplayer. Robinson’s daughter Sharon in an interview26 likened Chad and her father “as doing their job and doing it the best they can and carrying a weight on their shoulders.”27 She described the strength in her father’s character,

how difficult it was to suppress your voice—especially someone who was so outspoken; and that you’re doing it for the larger good; and the anger you feel, and yet you can’t express that anger on the field when you’re being attacked and you have to find ways to release it and still hold up your pride.28 [emphasis by original author]

In the postwar pressbook for the 1950 movie Robinson’s image is purely and successfully described as American, and there is no mention of race, or race issues. In fact, very few advertisements refer to African American culture in the pressbook. These pressbook advertisements clearly were not specifically targeted to attract African American spectators. Maybe there was an assumption that because Robinson was an important African American figure, they wouldn’t need to advertise to these moviegoers. Instead, this film falls in line with other kinds of nationalistic propaganda during the postwar period, a desire to present a strong global image of inclusivity. Robinson is presented as one more example of a heroic American.

Jackie Robinson discussed the making of the film in his autobiography, writing, “The producers wanted to make it before spring training, but I had been holding them up until the birth of my daughter…later I realized it had been made too quickly, that it was budgeted too low, and that, if it had been made later in my career, it could have been done much better.”29 Despite how inspiring and important Jackie Robinson’s story was at the time it seemed studio producers were reluctant to put forth full resources and attention to the making of the film. A swift release was more important. It seems more than likely that the rush to release this film was to fit it in with America’s Cold War need to prioritize positive nationalistic propaganda at the time.

This paper has revealed that pressbooks as marketing tools encouraged exhibitors to advertise based on what was happening during the period, inclusive of advertisements connected to a star or important figure such as Jackie Robinson. But they are open to complicated readings. The pressbook’s value lies in how it relates to its historical context. In the case of the Jackie Robinson pressbook, what it lets in and what it leaves out can teach us about ongoing struggles within American culture and what narrative is being screened at home and abroad.

received her MA in History of Design and Curatorial Studies from Parsons School of Design in 2021. Her area of specialization is twentieth-century American popular and material culture and its importance to the formation of social ideologies. She has been selected as a winner of this year’s Victorian Society New York’s Emerging Scholar contest to speak about fashion in Edith Wharton’s The Age of Innocence, both the novel and the Martin Scorsese 1993 film.

Notes

- Rudy Behlmer,ed., Memo from David O. Selznick (New York: The Viking Press Inc., 1972), 493-494.

- Ibid.

- Mark S. Miller, “Helping Exhibitors: Pressbooks at Warner Bros. in the Late 1930s.” Film History 6, no.2 (Summer 1994): 188, accessed January 19, 2021.

- The Jackie Robinson Story (United Artists Pressbook, 1950) (United Artists, 1950), 18, accessed January 19, 2021.

- Ibid, 10.

- Miller, “Helping Exhibitors: Pressbooks at Warner Bros. in the Late 1930s,” 188.

- Doug McAdam, Political process and the development of Black insurgency, 1930-1970—2nd Edition (Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 2010), The Historical Context of Black Insurgency, 1876-1954, Kindle.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Mary L. Dudziak, Cold War Civil Rights: Race and the Image of American Democracy (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2000), 48.

- Ibid, 48-49.

- The Jackie Robinson Story (United Artists Pressbook, 1950),6-7.

- Ibid, 8-9

- Ellen C. Scott, Cinema civil rights: regulation, repression, and race in the classical Hollywood era (New Brunswick and London: Rutgers University Press, 2015), 183.

- The Jackie Robinson Story (United Artists Pressbook, 1950), 10-17.

- Ibid, 10.

- Ibid, 11.

- Ibid, 12.

- Christopher Bergland, “The Guts Enough Not to Fight Back: Valuable lessons from Jackie Robinson (No. 42) on mindfulness training,” Psychology Today, April 12, 2013, accessed January 19, 2021.

- Christopher Klein, “Silent No Longer: The Outspoken Jackie Robinson,” History, April 14, 2017, accessed January 19, 2021.

- Ibid.

- Jackie Robinson and Alfred Duckett, An Autobiography of Jackie Robinson: I Never Had It Made (Ecco, 2013), The Noble Experiment, Kindle.

- Edward Cowan, “Freedom National Bank in Harlem Prepares to Open; Freedom National Bank Ready To Open in Harlem on Monday,” The New York Times, December 19, 1964, accessed January 19, 2021.

- Lesley Goldberg, “Jackie Robinson’s Daughter on Chadwick Boseman: ‘I See Parallels Between’ the Actor and My Dad,” The Hollywood Reporter, September 2, 2020, accessed January 19, 2021.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Jackie Robinson and Alfred Duckett, An Autobiography of Jackie Robinson: I Never Had It Made (Ecco, 2013), The Price of Popularity, Kindle.