Interviews & Reviews Issue 5 2021

Victoria Munro, Executive Director of the Alice Austen House

Margaret Simons

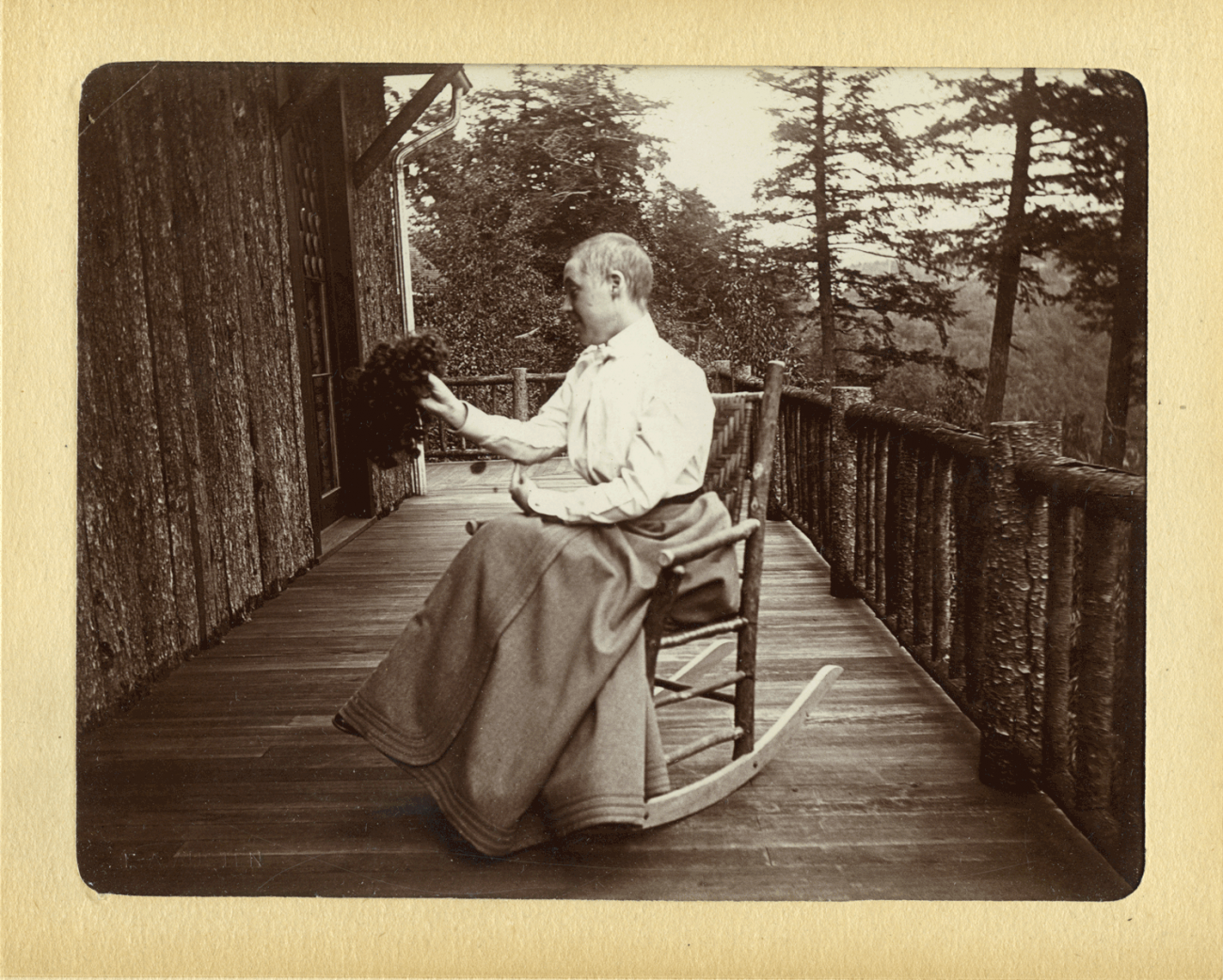

E. Alice Austen, Portrait of her home, Clear Comfort with John H. Austen in Rocking Chair on the Porch, 1885. Collection of the Alice Austen House.

Overlooking New York Harbor in Staten Island, the Alice Austen House (AAH) memorializes the life of its namesake photographer (March 17, 1866 – June 9, 1952). An early adopter of the technology of photography, Austen observed and captured New York City streets and everyday life at the turn of the twentieth century. In 2017, the AAH was recognized as a national historic LGBTQ site, an acknowledgement of Austen’s 50-year relationship with Gertrude Tate. As a Collections and Development Specialist at Alice Austen House, I was fortunate to interview the Executive Director, Victoria Munro, about the museum’s mission.

Margaret Simons: Alice was an accomplished photographer at the turn of the twentieth century, a time when photography was rare and its artistry unrecognized. Curatorially, how would you describe Alice’s underlying motivations as an image maker?

Margaret Simons: Alice was an accomplished photographer at the turn of the twentieth century, a time when photography was rare and its artistry unrecognized. Curatorially, how would you describe Alice’s underlying motivations as an image maker?

Victoria Munro: The difference between Alice and professional women photographers of the same era was that she photographed on the street, and she performed photojournalism which wasn’t even a genre yet. She was not in the business of making money by taking portraits of children and women which is where those professional studio photographers were poised. There was more of a level playing field between men and women at that time because photography was a new technology and women were being encouraged to take it up as a hobby.

I think Alice had professional aspirations. I think she is under-recognized because there has been this narrative about her being a hobbyist, and I don’t think that was the case at all. Certainly, later in life she became less ambitious, and I think that has to do with her settling into a long-term relationship with Gertrude Tate. She was most prolific in the last decade of the nineteenth century. If you look at her photographs from 1890 to the turn of the century, there’s just so many photographs and all of her themes are represented in that period. She met Gertrude in 1899, and the photographs started to become more about domestic life. We stop seeing the street types in her work, and her photography of the quarantine stations stops. [Alice documented the quarantine process when immigrant ships arrived in New York, including the station on the Staten Island shore and the quarantine facilities on Hoffman and Swinburne Islands in New York’s Lower Bay.] So, while we don’t have Alice’s voice to talk to this, I would say during the period before the turn of the century, Alice was taking professional jobs. The photos of the quarantine stations were put on display at the 1901 Pan American Exhibition in Buffalo in the Sanitation Wing to show the new technology for quarantining. She self-published her street types and obtained copyrights on those photographs, so that’s a real indication of saying, “I’m entering this business.” There is also a letter our Collections Associate just shared with me where Alice is being asked by another woman to publish photographs Alice had taken in the Catskills.

Boot Black street type: An image from Austen’s Street Types series. E. Alice Austen, Bootblacks, 1896. Collection of the Alice Austen House.

MS: The AAH undertook a complete interpretative renovation from 2018-19 where the interiors of the house were converted from a period-room approach to a streamlined display of Alice’s life and work exhibited under the title New Eyes on Alice Austen. Can you describe the factors driving the change?

VM: There was an initial planning phase for the reinterpretation of AAH funded by a National Endowment for the Humanities grant where scholars came together. LGBTQ scholars and critical thinkers gathered together, and it was monitored by an external person who was hired to run that process. They spent one weekend at the AAH and then each of them went away and wrote a recommendation about how they felt about various issues including how we would talk about Alice Austen and how she lived her life. The general consensus was that the house needed to be reinterpreted, but it needed to be interpreted with a guiding theme that was “home”.

For this particular story we are so lucky at the AAH because we have a massive narrative and we have lots of imagery. We’re not wanting to change the architecture of the house so the architecture is still there, but we didn’t want to fall into the trap of just copying what is in Alice’s photographs. It’s really core to the story that Alice lost all of her money and lost her house. Alice lost her inheritance with the 1929 market crash. Alice and Gertrude were evicted in 1945, and Alice eventually moved alone to the poorhouse. Gertrude’s extended family would not allow Alice to live with them, and Alice lost her furnishings. While we like owning some of Alice’s objects, which are fantastic and we put [them] on display, we have her photographs to tell the story and we want the public, scholars, students, and young children to be looking at these rooms through Alice’s lens. The reinterpretation of the house put Alice’s photography front and center. And while Alice had relationships with other women, the 53-year relationship with Gertrude Tate was important to feature as part of the story of the house.

Picture of Alice Austen House. Clear Comfort, 2015. © Floto + Warner.

MS: Describe the process of reinterpreting the Alice Austen House to incorporate its LGBTQ context?

VM: It was easier for us to incorporate Alice’s LGBTQ history and receive a national LGBTQ designation because we were already a nationally designated landmark—we were already in the registry. Andrew Dolkart, who is an amazing historian with particular focus on LGBTQ interpretation, worked with the National Parks Service to amend our designation to include LGBTQ history as an area of significance. At that time, 2017, there were only fourteen sites nationally [designated as LGBTQ landmarks] and in New York there’s sites with regional or state [LGBTQ] designation, but with regard to national designation, we were one of only four. It’s a huge responsibility to get the interpretation right. If you are going to accept this designation and go after the amendment, it’s important that you are not passive about it; you have to actively program the site to tell those narratives, and not just to tell historical narratives but to be inclusive of the community that has been oppressed for so long and make amends with the LGBTQ community who have long known that Alice was a lesbian.

Self portrait of Alice. E. Alice Austen, E. A. A., 1892. Collection of the Alice Austen House.

MS: The United States’ historic homes have been expanding the inclusivity of their narratives to incorporate the stories of all those that have been connected to these houses, whether enslaved, indentured laborers, or maid servants, in order to offer a broader picture of the American experience through them. How has AAH modified its interpretation to offer a more expansive view?

VM: One of the most important things that we do is we work with what we know. We don’t make it up because any other storytelling that needs to happen in the house can be created by the people that come to it. We have centered the LGBTQ narrative through text and quotes, and we’re lucky because we have a photo collection that includes photographs of Gertrude.

Alice was obviously very close with the three Irish maids that worked here so including them on the family tree was really important, and also, of course including Gertrude. The general thought is, and I agree with it, is that she had a very close, benevolent relationship with these young women. The maids stayed with them, and Alice photographed them affectionately. She photographed them having fun in the snow, etc., so the photographs of the maids feel very personal. The three maids would have been up in what we now have as the collections room. It’s a very small space, but they were very necessary to care for the home given the amount of work required to bring water into the house and other domestic duties.

The most important thing I dealt with in the permanent installation is to include representations of other members of the family or people that lived in the house because there’s no room in those conventional, standardized family trees for other models of what a family is. Often there’s no room in historic houses for an expanded definition of a family. We work a lot with kids that are new immigrants and they’re not necessarily here with their parents—they’re living with grandparents or with aunts—that can be quite upsetting. It’s good for them to realize that there were different definitions of family even in the nineteenth century.

MS: The renovation also incorporated contemporary exhibition space; the most recent exhibition, Powerful and Dangerous: The Words and Images of Audre Lorde, will be on display until March 2021. How do you plan for future shows and what are the primary considerations behind the contemporary exhibition selections?

VM: We always start off by thinking about Alice. Initially, it was urgent for me to include queer and contemporary narratives—that’s still a big part of it. What we haven’t done a very good job of in the past is making allocations and space to include artists of color.

Moving forward with our programming, a key consideration is representation and inclusion. It’s also striking a balance between investigating what is vernacular photography and art photography and looking at the ways photographers represent themselves. I’m very interested in investigating that because it feeds into our education programs where we ask students to explore their own personal identities through photographic storytelling.

MS: Alice was an active community member of her Rosebank neighborhood during her lifetime. Given that lens, how does AAH define contemporary community and engage its audience?

VM: These are huge issues for us at AAH because we prioritize teaching in Title I schools on the North Shore, engaging those communities with our programming, but also allowing space for those communities to use and enjoy our park. Obviously, there’s a lot more to be done to engage families and have them use the park and feel welcome to come into the museum. They have to be able to also see representations of themselves in the museum, and the contemporary galleries are a portal to that, so we have this opportunity to connect with the community.

MS: How did the pandemic impact AAH including the visitor experience, exhibition schedule and programming? How do you think the pandemic adjustments will impact AAH curatorial approach going forward?

VM: Everyone has pivoted to the virtual and this concern has become integrated into the planning around curation. We work with the assumption that you might not be able to do that in-person work. We were already moving in that direction. For example, our app[lication] allows for a self-conducted tour of the museum from anywhere. I think, interestingly for a curator, Covid has made us more collaborative than ever. I think we have become these Zoom machines that talk all day, and whilst it’s very exhausting, in terms of curatorial work, it’s very good because it’s expanding so that more voices are on board. Because of Covid, the Audre Lorde exhibition was extended for the entire year, which meant that the period of time that I spent working with the contributors was extended. The show grew over the course of the year and more relationships were started and developed. For example, the relationship with Audre’s daughter. We’ve made connections between AAH and her that are lasting.

MS: AAH exists on land owned by the NYC Parks Department, and the organization that you lead, the Friends of AAH, maintains and operates the museum. What is the curatorial approach to the use and interpretation of the grounds outside of the house?

VM: As you know the grounds are beautiful and there’s a lot of work that needs to be done to interpret them fully. The rich history of the waterfront location of the AAH and Alice’s use of her garden as a studio offers several curatorial opportunities. We need to explore the idea that gardens and gardening provided safe spaces for women to meet and socialize, which of course Alice made the most of as a founder of the Staten Island Garden Club. There are these rich female-centric narratives that can be explored in and through the outdoor space. I think it’s also important to acknowledge what came before and that’s not something that has happened yet in this park. This would have been a site where the Lenape may have resided; they certainly would have used the resources from the harbor. There are large oyster colonies all along the North Shore—so there’s a lot of work to be done there to tell that story.

Gertrude Tate with her wig removed. E. Alice Austen, Gertrude Tate With Her Wig in Her Hand, 1899. Collection of the Alice Austen House.

MS: What is your favorite photograph or object from the museum’s collection and why?

VM: It’s the album that Alice made for Gertrude after they had met in 1899 in the Catskills at Twilight Rest resort. AAH purchased the album… about eight to ten years ago, so we haven’t had it in our collection for very long. It’s inscribed to Gertrude, and it has these two important photographs where Gertrude was recovering from typhoid fever and she had lost all her hair, and she allowed Alice to photograph her with her wig off and that’s just a really intimate thing to be allowed to do.

received her MA in History of Design and Curatorial Studies in 2021 from Parsons School of Design. She is currently a Collections and Development Specialist at Alice Austen House. Prior to joining AAH, she held curatorial fellowship positions at the Museum of Modern Art and Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. Her MBA and prior career in finance informs her interest in the intersection of design and commerce.