Essays

The Embroidered Arts in Colonized Mexico and Indigenous Craft

Gregory Scott Angel

“Threads join the body to nature and the universe. When these garments [or pieces] stories are recounted in the form of words, something emerges that could even be considered a kind of fantastic literature. Embroidery as a form of writing unleashes in its creator a flood of marvelous images associated with myths of incalculable age. It is therefore easier to use images that can be seen and interpreted varyingly than to try to explain the concepts.” Margarita de Orellana.1

This essay explores the relationship between Spain and Mexico through textile arts, following Spain’s colonization of Mexico in the sixteenth century and into the eighteenth century. It looks at how embroidery was used by the Spanish to educate and convert indigenous Mexicans to Christianity. Young women, in particular, learned the art of embroidery from a Eurocentric perspective, but they borrowed iconography and motifs from both Spain and Mexico. New commodities employing needlework imported from Spain and Manila, such as rebozos and colchas, further disseminated this mix of traditions. Additionally, this paper acknowledges an indigenous tradition of embroidery in Mexico and Amerindian iconography that pre-existed the country’s colonization.

Embroidery guilds were established by the Spanish around the viceregal capitals of Mexico in the sixteenth century and were dedicated to creating elaborate vestments for Spain’s Catholic Church and training indigenous Mexican people in European methodologies and craft. During the colonial era, Veracruz, Mexico’s Atlantic port, served as the main entry for the importation of livestock, artisans, and church missionaries from Spain, and, in return, goods such as chocolate, gold, silver, and cochineal from Mexico were exported to Europe.2 Textiles and embroidered clothes were among those goods Mexico exported to Spain. In the book Clothing the New World Church, Maya Stanfield-Mazzi writes about these Mexican textiles, saying, “Master embroiderers and their teams of assistants and apprentices… confected rich pieces that are often indistinguishable from Spanish examples,”3 Such traditional vestments were often adorned with silk thread and precious metals, depicting stories from the Bible, as well as important church figures, or “miracle” scenarios including saints. Sacred garments were commissioned by Spain’s Catholic church from Mexico for clergymen favored by wealthy patrons. Fine examples can be found within museum collections and private church inventories, and, as they were only worn on specific occasions, they exhibit less distress than other garments.

During the late seventeenth century, naturalistic floral embroidery inspired by Chinese and Persian style needlework rose in popularity in Europe, alongside the more traditional biblical scenes.4 Referred to as pintura a la aguja (Spanish for needle painting), this style of embroidery enables the embroiderer to shade objects or iconography with long and short stitches, allowing for subtle color changes to give a realistic nature to the subject [flower].5 Embroiderers in Mexico were especially adept at such intricate flower work, sometimes referencing floral embroideries imported from Manila through Acapulco. Pintura a la aguja was often commissioned and produced with fine silk threads dyed in multiple colors and shades, performed in satin stitch, and carefully layered to replicate the naturalistic color exchange in flora found in paintings, imported objects, picture books, or local gardens and surrounding fields near the viceregal capitals. To offset the colorful flora, threads wrapped in gold and silver were used to create a visually stunning background similar to other European textiles, such as tapestries.6 Precious metal-wrapped threads were made by skilled metal workers who would draw the alloy and pound it into extremely thin strips to wrap silk floss in various colors, mostly yellow, white, or green. Two different techniques were used in applying these metal threads to cloth: surface application (couching) and under-side couching. While surface couching was more common, under-side couching grew in popularity due to its singular stitch appearance in Europe and England.7

FIG. 1 Stoles, Early 18th century, Spanish. Silk, metal, 42 in. (106.7 cm). Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Gift of the Rembrandt Club, 1911. 2009.300.2270.

A set of stoles from the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Fig. 1) and a cope from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (Fig. 2) reveal the embroidery techniques used in Spain and introduced into Mexico during the beginning of the colonial era.8 The stoles, listed as manufactured in early eighteenth-century Spain, shimmer with a horror vacui background laid in gold and silver and vibrant colors depicting flora and fruit varietals. These stoles are untraditional in decoration by covering the entire surface with multiple colors of dyed silk and precious metal-wrapped threads in contrast to a more usual humble fabric ground of linen.9 Stitched with a naturalistic rendering of flowers, the stoles were meant to be worn by two priests or clergy, standing side-by-side during worship, which would exemplify and intensify the magnificent nature of these pieces.10 The stoles exhibit almost a perfect mirror image of each other, implying the context of production by the same manufacturer, under the same guidance or master embroiderer, and using the same materials.

FIG. 2 Set of Ecclesiastical Vestments (Partes de un terno eclesiástico) Cope with Hood (Capa pluvial con capucha), Attributed to Workshop of Manuel José de Mena Cárdenas (Mexico, 1711-1752), Mexico circa 1730. Silk satin with silk and metallic-thread embroidery and metallic braid trim, 53 in. (134.6 cm). Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Costume Council Fund (M.85.96.7a-b)

In comparison, the LACMA cope, which is part of a set of Ecclesiastical Vestments attributed to the workshop of Manuel Jose de Mena Cardenas in Mexico City,11 is fully embroidered with floral-like patterns and an elaborate background shimmering in punto de oro, gold-wrapped yarns couched in elaborate formations. The laid goldwork is configured to replicate brickwork and basketry stitchwork.12 Similar to the stoles, the cope exhibits a mirror image of motifs with variations and adjustments to the objects in shape or artistic replication. On the front band, framed by a stitched ornamental chain braid, we see sumptuous vegetation, wildflowers, and exotic birds captured in different colors, both indigenous to the Americas and other Spanish-settled areas. But we also see two motifs, neither flora nor fauna; instead, a European-style tiered fountain and a roundel filled with an unidentifiable object are rendered. Interestingly, the fountain is considered a symbol of the Virgin Mary, and “the tower, fountain, palm[s], flowers, sun and moon… [as well as] blue birds, perched on coral-colored flowers with youths bearing fruit… were all used to convey the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception.”13 The cope, along with other pieces in LACMA’s Set of Ecclesiastical Vestments, presents many more images of Mary’s conception as interpreted by Spain’s Catholic church in combination with indigenous imagery.

According to the Franciscan missionary Toribio de Benavente Motolinia, European embroidery techniques were taught to Mexican peoples by Brother Daniel, an Italian master embroiderer from Santiago, Spain around 1528.14 He is possibly the same Daniel mentioned in Stanfield-Mazzi’s book who taught embroidery techniques at the Colegio de San Jose in 1527, near one of the main import cities of Veracruz.15 While opportunities for both Spanish immigrants and indigenous Amerindians were available in Mexico through embroidery guilds established there in the mid-sixteenth century, working with specific materials, such as precious metals, was limited to Spanish embroiderers, who passed the appropriate examination requirements.16 However, other opportunities to learn embroidery skills were offered to indigenous people through educational academies and convents, which also served to prepare native youth for Euro-Christian life in Mexico or New Spain.

Floral style embroideries, or “flower work,” in Mexican embroidered pieces, for example, have been attributed to young women at beaterios, religious schools run by Franciscan missionaries and nuns in the mid-eighteenth century.17 In this way, Mexican girls from different social classes were taught the importance of a Christian education as well as embroidery techniques as a way of measuring their skills in needlework and recording their achievements. Fray Motolinia, considered one of the Twelve Apostles of Mexico, arrived in the New World in 1524 and recorded “that an effort was made to educate the daughters of nobles and dignitaries [through] devout Spanish ladies who taught Christian doctrine and the art of embroidery.”18 These achievements and educational records exist on plain cloth fabric, known as samplers. “Samplers were [considered a task in] preparation [of] adult life.”19 Women were taught that their needleworking skills were necessary to navigate their lives through marriage and prepare them to manage their households and record their family histories and memories. Similar educational training existed for young women’s livelihood in Europe.20 While these skills were emphasized as “colonial and Christian” teachings, there is significant evidence that embroidery [and textile production] were already assimilated in “women’s activities, social roles, and subjectivity across a millennium of Mesoamerican history” or prior to the Spanish colonization of Mexico.21 The familiarity of these skills would have aided the ease and transition into Christianity for many indigenous youth.

Educational art academies established in Mexico City to promote the “three noble arts” of painting, sculpture, and architecture were also adopted by embroiderers during the latter half of the eighteenth century. Convents were established in Mexico City and Puebla by the nuns of Santa Catalina de Sena first as a beaterios in the early part of the17th century.22 “In 1755, the first free public girls’ school was established in Mexico City by the nuns of Ensenanza (Colegio del Pilar), and it instructed its students in reading, writing, and needlework.”23 Samplers were used as both a test of skill and dexterity; they were an attestation to one’s skill level and part of the application for entrance into Mexico’s embroidery guild. These samplers contain iconography at the intersection of Spanish influence and traditional Mesoamerican craft.24

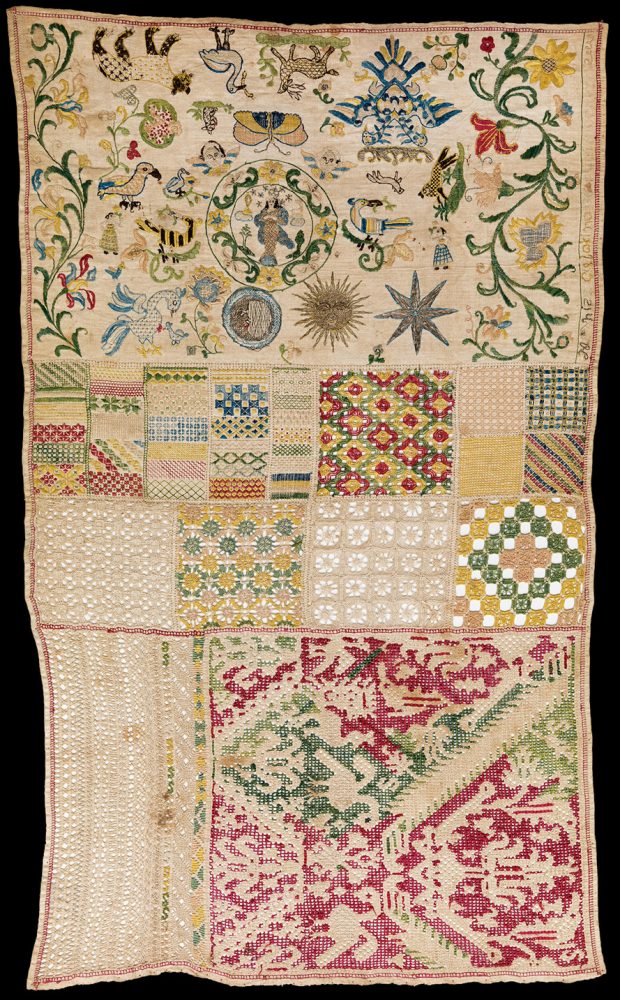

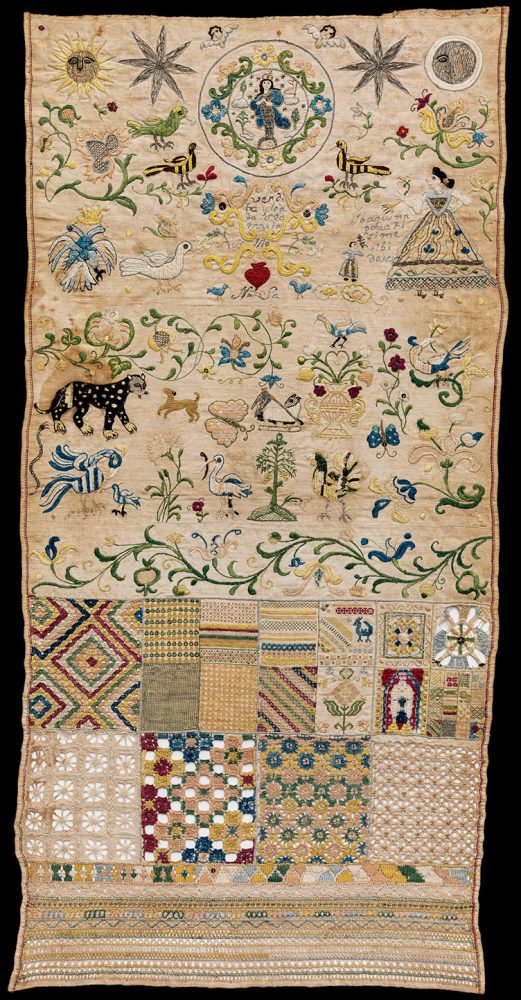

A sampler dated to nineteenth-century Spain displays a wealth of stitches and drawn threadwork in multiple-colored patterns and techniques. Embroidered by Anna Navarro, the sampler has five distinct sections performed in both cross- and satin stitches. Some geometric squares exhibit an Italian-like gradient, similar to the Florentine stitch, also referred to as punto de llama or “flame stitch.” No official documentation explains the cross-cultural shading and stitching technique associated with Spanish embroideries, except for the transdisciplinary movement of Italian craft in Europe in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. The geometric styles of the Spanish sampler, however, can be compared to Mexican samplers, such as two examples from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Attributed to women in 1785, the two dechados, embroidered by Catarina (Fig. 3)

and Joaquina (Fig. 4), compare to the Spanish sampler in having a larger format and including symbolism and iconography associated with both Spain and native Amerindian life. Joaquina’s sampler displays a large section of motifs in drawn-work below a series of borders. Catarina’s sampler shares similar motifs found in Joaquina’s dechado, but the thread paints an elaborate configuration of cross-stitches performed in green and crimson threads. The motifs shared between the two Mexican samplers include the sun, moon, and stars, “motifs associated with the Immaculate Conception”; the jaguar, a pre-Colombian symbol of Mexican Deity with the ability to move between the worlds, also representing authority, power, and the ferocity of indigenous warriors;25 a central female figure, encased in a circle of satin stitches, filigree, and flora, which represents the Virgin Mary and other ascetic motifs such as winding vines, flowers, and leaves; and the double-headed eagle, a symbol of the Habsburgs and Holy Roman Empire, as well as the alliance between Quauquecholteca and Spanish colonists.26

Cross-stitch and geometrically detailed cut-work in various colors are represented in both the Spanish and Mexican motifs. Eight-petaled flowers and contrast-colored rhombi set inside one another appear as a recurring pattern.27 Diamond shape-in-shapes are a representation of the cosmos or the earth between the heavens and the underworld. This motif portrays the Mayan notion of the world as a square using the sun at the center, dual symbolizing Jesus Christ.28 Joaquina’s sampler also contains a small cross-stitched version of the Tree of Life, a European symbol of the connection between heaven and earth; a double-headed eagle in drawn-work (far left corner in blue silk with light brown and green accents); our Lady of Guadalupe (small square with a red background in white and blue accents); a box of twelve miniature stitched cubes; and what might be considered a Pecked Cross (drawn and stitched in light blue, with an “X” in navy and light brown).

FIG.3 Sampler (Dechado), Catarina, Mexico, circa 1785. Linen plain weave with silk and metallic-thread embroidery, drawn work, and needle lace, 39 1/4 × 23 1/4 in. (99.7 × 59.1 cm), Costume Council Fund (M.82.105.2), Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

FIG. 4 Sampler (Dechado), Joaquina, Mexico, circa 1785. Linen plain weave with silk and metallic-thread embroidery, drawn work, needle lace, and metal sequins, 40 7/8 × 20 1/4 in. (103.8 × 51.4 cm), Costume Council Fund (M.82.105.1), Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

The Pecked Cross is a symbol associated with Mesoamerican petroglyphic design, which could be a representation of the Piedra del Sol (Aztec Sun Stone), an ancient Mayan calendar etched in rock and attributed to the reign of Moctezuma. The cutwork, similar to crocheted squares, is a common motif in women’s clothing, like huipiles or skirts. The origin of drawn thread work, void of color, stems from another form of embroidery taught to young girls in Spain and then Mexico as part of their education called whitework.

Whitework featured intricate white threads on a white ground and was produced and used for liturgical services and clothing applique. This skill and craft of cut- or drawn-thread work, known as deshilado, is the art of pulling threads from the ground fabric to create a negative space, emphasizing motifs or selected iconography. Once the thread is removed, embroidery stitches are introduced to reinforce the positive outline, and knots or tied stitches reinforce the remaining threads into the structural pattern or shape desired; the overall effect looks similar to lace work. This practice was used in Spain to embellish garments for christenings, table runners, vestments, and other liturgical needs.29 Female convents were a primary source for embroidery and needlework commissioned by the church for items such as embroidered albs and altar cloths.30

FIG. 5 Sampler (Dechado), 1869, Mexico, Linen, cotton, H. 15 1/8 x W. 15 1/8 in. (38.4 x 38.4 cm) Gift of Alfred L. Bush, 2011, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2011.578.1.

The geometry and symmetry of white work bear a striking resemblance to yet another form of embroidery, popularized in the 16th century and wrongly attributed to Catherine of Aragon: blackwork.31 Blackwork is a series of running-, back-, or “holbein” stitches used to create geometric patterns, symmetrically placed with black thread on a white linen ground. These patterns were used as embellishments to cuffs, sleeves, or a full ensemble. The patterns of flora or fauna were replicated realistically with tiny counted stitches in multiple configurations. To understand the comparison and connection, one can view a beautifully intact sample of whitework from the Metropolitan Museum of Art against a black work sampler from the Baltimore Museum of Art. The MET’s whitework dechado, dated 1869 and from Mexico, is performed on white linen and cotton backing (Fig. 5). Little is known about this sampler, which was purchased by a woman visiting Mexico and later gifted to the MET by Alfred L. Bush. Approximately the size of a handkerchief, the piece features stain-stitched scalloped edges, holding the shape of the delicate article. The center is broken into five areas: four quadrants and a centerpiece. An embroidered laurel wreath sits at the center with the initials “T.E” and the date 1869. The four quadrants exhibit similar motifs diagonally, with variations in artwork of the butterfly and florals. Embroidered eyelets provide a distraction to the solid-stitched foliage, and scallop-shaped pods border the entire cloth. Twenty-four shapes are performed in twenty-four different geometric patterns, similar to the drawn work in both Mexican dechados by Joaquina and Catarina.

FIG. 6 Blackwork-Sampler-1500-1700-Europe-Linen ground-silk-embroidery-threads-Gift-of-Dena-S.-Katzenberg-Baltimore Museum of Art 1975.68.3

These negative-space patterns bear a striking resemblance to blackwork patterns on the Spanish sampler (Fig. 6). A close look at the various shapes and intricate details, especially the “x’s’, ‘diamonds, and rhomboid shapes positively stitched in black silk thread, are reinterpreted and performed in white. While there are many differences between the Mexican and European examples, the similarities evidence the dissemination of European artistry taught to and executed by ‘New World’ fingers.

Trading ports on both the east and west coasts of Mexico assisted the budding infrastructures of embroidery guilds, introducing non-traditional styles and different kinds of textile commodities to native Amerindians. From Spanish-colonized Manila, for example, rebozos, or embroidered shawls, were introduced into Mexico during the colonial period, and all classes of people used them. “Rebozos were not only utilitarian but were presented to young women to mark special occasions, such as their entrance into a convent.”32

FIG. 7 Shawl (Rebozo), Late 18th Century, Artist/maker unknown, Mexico. Silk plain weave with resist dyeing and silk and gilt thread embroidery in darning, satin, and outline stitches with knotted fringe, 30 x 90 in (76.2 x 228.6 cm), Gift of Mrs. George W. Childs Drexel, 1939, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1939-1-19.

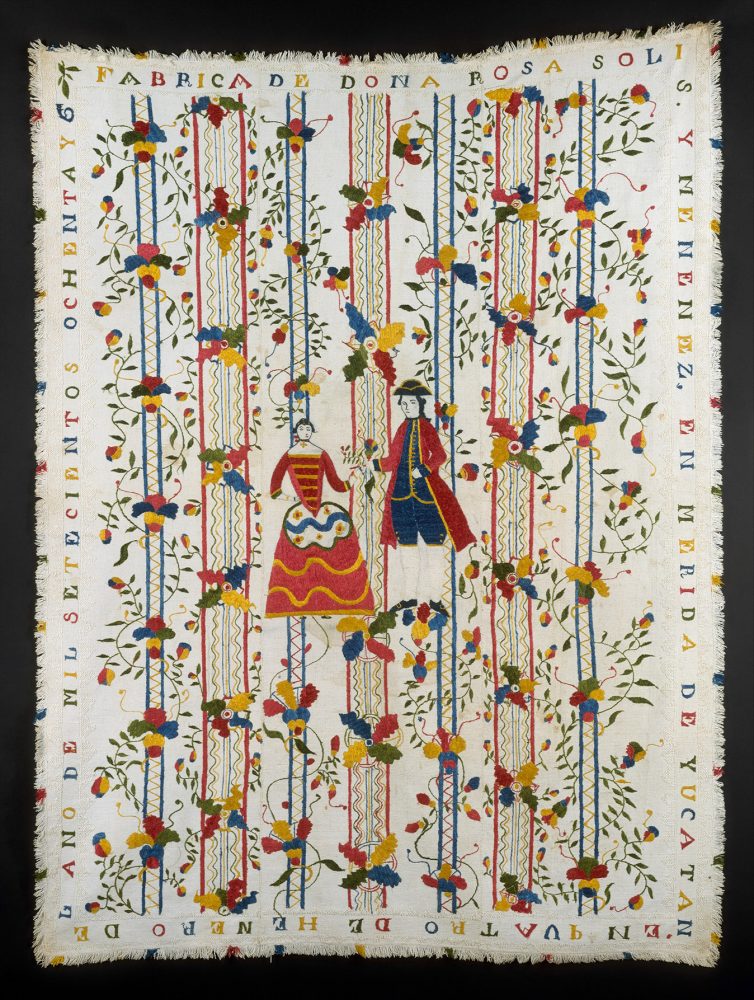

An example of this style from the late 18th century is in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art (Fig. 7). Measuring thirty inches wide and seven and a half feet long, the rebozo is an example of Mexican craft but with a transatlantic narrative. The motifs depicted include European-style dressed figures, boats, outdoor activities, and other leisurely pursuits popularized in Mexico City during the 18th century. As rebozos evolved, they included fringed edges and figurative silk embroidery and became a recognized symbol of Mexican heritage and textile craft.33 Colchas, another embroidery form developed from the European tradition for comfort (also often referred to as coverlets), found prominence in northern Mexican life. Traditionally woven with wool yarns from the churro sheep as well as embroidered, colchas have a unique origin that borrows from traditions as far as Boukharra to Spain and Portugal. They popularized colonial imagery and were made by Hispano Americans in the modern states of Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and southern parts of Colorado. Decorated with a self-laid stitch, “colcha [stitching] is a long, self-couching stitch, secured to the ground cloth by anchoring stitch[es].”34 These stitches create a variety of stylized flowers, vines, leaves, and religious motifs inspired by Catholicism, as well as Moorish arabesques, Indian chintz, and the desert landscape. A surviving example of an 18th-century colcha produced by Rosa Solis y Menedez is part of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s collection (Fig. 8). “Embroidered in bright-colored silk on a textured cotton ground, its lively imagery celebrates love and marriage.”35 The example exhibits two figures dressed in Spanish-style clothing, centered on a colorful background of trellises filled with climbing flowering vines as a European symbol of marriage. The combination of both symbols and iconography supports the intercultural exchange, blending Spanish iconography and techniques with newly colonized beliefs and religion.

Fig. 8. Embroidered coverlet (Colcha), Doña Rosa Solís y Menéndez, 1786, Made in Mérida, Mexico. Cotton embroidered with silk, 100 x 73 in. (254 x 185.4 cm), Purchase, Everfast Fabrics Inc. Gift, 1971, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1971.20.

Embroidery techniques and imagery in Mexico materialized and flourished under Spain’s influence with the introduction of new fibers, technical practices, and craft masters. However, embroidery techniques, as noted earlier, existed prior to Spain’s colonization of Mexico. Recent research documents Pre-Hispanic embroidery in the works of Fray Bernardino de Sahagun, a sixteenth-century chronicler of the Aztecs who documents work composed with tlamachtli, Spanish for embroidery, and declares his amazement at the skills of indigenous women and their ability to perform intricate needlework.36

Clothing or articles with needlework were a part of both men’s and women’s daily lives and were worn in various areas of Mexico. “In many regions, garments display[ed] increasingly large areas of needlework… Satin-stitched animals, birds, foliage, and flowers adorn huipiles, skirts, blouses, and servilletas in a number of villages” as well as conjoined fabrics for sarapes and other articles of clothing.37 Groups, such as the Highland Totonac, Tepehua, Otomi, and Nauha, used embroidery as decoration to women’s garments as well as adornment for ceremonial clothing.38 Geometric designs covered the ground fabric and communicated symbolism when stitched into the garment for whom it was made. Graphic flowers, for example, appear on many textiles as a “[symbol of] fertility, beauty and divinity, life, and the regenerative properties of death.”39 Fibers and dyes used in crafting pre-Columbian Mesoamerican fabrics were also associated with the women weaving and embroidering the textiles. “Women were the spinners and weavers and also, apparently, the ‘embellishers,’ adorning clothing with garnishes of embroidery, feathers, or fur.”40 Symbols, foreign objects, and other materials were integrated into their culture and embroidered onto their textiles to feature “history, myths, rites, dreams, and everyday experiences.”41

Understanding and preserving the artistry of pre-Columbian Mesoamerica is an opportunity to learn ancient practices inclusive of different fibers and dyes and their association with life and household practices. Chloe Sayer writes, “It would be sad indeed if the long evolution of Mexican [textile arts] should end… with the uniformity of Western [practices, as] civilization would be poorly served by the loss of textile [and embroidery] skills that have endured for countless centuries.”42 Combining the origins of traditional textile practices of indigenous Mesoamericans and the disseminated arts of European craftsmanship establishes new narratives that can explain the proper provenance of embroidery practices that have survived from the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries in Mexico.

Gregory Scott Angel is a patternmaker/tailor, and historical textile researcher. With a background and interest in haute couture and traditional tailoring techniques, he shares his expertise and talent by teaching construction, patternmaking and technical studio classes at Parsons. He also consults with start-up brands on product development and operates his own creative studio. His textile research is rooted in the art of embroidery and craft of Latin America.

NOTES

- Margarita de Orellana, Alberto Ruy Sánchez, and Eliot Weinberger, eds. The Crafts of Mexico. Washington, D.C: Smithsonian Books, in association with Artes de México, 2004.

- Ida Altman, S. L. Cline, and Juan Javier Pescador. The Early History of Greater Mexico (Upper Saddle River, N.J: Prentice Hall, 2003), 119.

- Maya Stanfield-Mazzi refers to the Mixtec Codices that provide an account of pre-Hispanic Mexico and genealogy documents that survived the Spanish conquest. Maya Stanfield-Mazzi, Clothing the New World Church: Liturgical Textiles of Spanish America, 1520-1820 (Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press, 2021), 69.

- This popularity and change could also be attributed to the influence of Spain’s sovereign, Philip the V, son of Louis, the Grand Dauphin, and grandson to King Louis XIV of France and Maria Theresa of Spain. Philip was born in the Palace of Versailles and would have been familiar with various ornamental styles that were changing at the time, including the popularity of realistic floral embroidery, introduced by Italian artisans who were brought to France to create a preeminent center for decorative arts, crafts, and music.

- Victoria and Albert Museum. “Mexican Embroidery · V&A.” Accessed January 26, 2023 https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/mexican-embroidery.

- Embroiderers also began to use gold thread in the unique technique known as underside couching. The main thread was made of silk, around which a narrow, flat band of gilt silver was wrapped. Since this thread was difficult to pass through the base cloth, embroideries used sturdy, two-ply linen couching threads to draw tiny loops of the metal thread through to the back of the base cloth, hiding the coughing stitches and creating small “hinges” in the metal thread. This gave the finished embroidery [and fabric] more pliability [flexibility] and dimension than that found in works made with surface couching. Lisa Monnas, The Making of Medieval Embroidery, English Medieval Embroidery, Opus Anglicanum, 14-15.

- Clare Woodthorpe Browne, Glyn Davies, M. A. Michael, and Michaela Zöschg, eds. English Medieval Embroidery: Opus Anglicanum (New Haven: [London]: Yale University Press; In association with the Victoria and Albert Museum, 2016), 7-23.

- A cope is a semicircular vestment worn as a ceremonial dress and is used as a processional garment versus others used during mass. It is worn over the shoulders and fastened by a strip of material or an ornate brooch. A stole is a long, narrow strip of fabric, elaborately decorated, and can be worn by a deacon, priest, or bishop. Dobrila-Donya Schimansky. “The Study of Medieval Ecclesiastical Costumes: A Bibliography and Glossary.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 29, no. 7 (1971): 313-17.

- “The art of embroidering, and especially of embroidering with the aid of gold and silver thread, was communicated to the Spaniards by the Spanish Moors, who doubtless had derived it from the East. By about the thirteenth century, the needle of the Spanish embroiderer had become, in the picturesque phrase of one of his compatriots, “a veritable painter’s brush, describing facile outlines on luxurious fabrics, and filling in the spaces, sometimes with brilliant hues, or sometimes with harmonious, softly-graduated tones which imitate the entire colour-scheme of Nature.” “The Arts and Crafts of Older Spain, Volume III (of 3), Leonard Williams.” Accessed January 3, 2023. https://www.hellenicaworld.com/Spain/Literature/LeonardWilliams/en/ArtsAndCraftsOfOlderSpain3.html#EMBROIDERY.

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Stole | Spanish.” Accessed January 26, 2023. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/157078.

- “Set of Ecclesiastical Vestments (Partes de Un Terno Eclesiástico) Cope with Hood (Capa Pluvial Con Capucha) | LACMA Collections.” Accessed January 26, 2023. https://collections.lacma.org/node/250234.

- Stanfield-Mazzi, Clothing the New World Church, 106

- Stanfield-Mazzi, Clothing the New World Church, 106.

- Joseph J. Rishel, Suzanne L. Stratton, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Antiguo Colegio de San Ildefonso (Museum), and Los Angeles County Museum of Art, eds. The Arts in Latin America, 1492-1820 ( Philadelphia, PA: Mexico City: [Los Angeles]: New Haven: Philadelphia Museum of Art; Antiguo Colegio de San Ildefonso; Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Yale University Press, 2006), 152.

- The influence of Italian workmanship is evident both in documentation as well as LACMA’s own collection. An Italian cope from approximately the same time shares similar leaf structures and scrolling vines (https://collections.lacma.org/node/178302). Oddly, there is no comparison to the magnificence or splendor between both pieces. Stanfield-Mazzi, Clothing the New World Church, 88.

- Rishel et al., The Arts in Latin America, 1492-1820, 152.

- Stanfield-Mazzi, Clothing the New World Church, 106.

- “La conquete spirituelle du Mexique (The Spiritual Conquest of Mexico)” by Robert Ricard examines the historical process of the first missionaries who were tasked with converting the Indians in Mexico. Stresser-Pean details the ways that conversion was initiated by the Spanish missionaries in Mexico. Guy Stresser-Péan, The Sun God and the Savior: The Christianization of the Nahua and Totonac of the Sierra Norte de Puebla, Mexico (Boulder, Colo: University Press of Colorado, 2009), 8.

- “V&A · Mexican Embroidery.”

- Sheila Paine and Imogen Paine. Embroidered Textiles: A World Guide to Traditional Patterns. Revised and Expanded, First paperback edition (London: Thames & Hudson, 2010), 153.

- The premise of this addition points to anthropology work found in the illustrations of the Aztec Florentine Codex, which was composed shortly after the Spanish Conquest in 1524. Elizabeth Brumfiel writes on the production of cloth via a backstrap loom and the performative nature and roles of women in early Aztec textiles. The article decodes different aspects of fibers in connection to cloth production, including what they were used for and what they represented in Aztec Mesoamerica. Brumfiel, “Cloth, Gender, Continuity, and Change,” 862.

- Paine and Paine, Embroidered Textiles, 172.

- Many samplers are attributed to a singular name, but there is no educational institution listed, as these are singular entities, showing that education in the arts existed in Mexican schools. “Orphan girls attended academies, the first of which was established in 1543, where they were taught embroidery, sewing, and spinning flax and wool, among other skills. [By] the mid-eighteenth century with the establishment of an academy by the Society of Mary that reading and writing became part of a girls education.” Paine and Paine, Embroidered Textiles, 153.

- The existence of pre-Columbian embroidery is a continuous subject of interest and research. Based on Mayan archaeological records, Arlen R. Chase, Diane Z. Chase, Elayne Zorn, and Wendy Teeter collaborate by documenting the following, “Textiles were of great importance to ancient Mesoamerica. For the Aztecs, Maya, and other peoples of Mesoamerica, finished textiles were widely traded and commonly used for the payment of tribute. Textiles were also used to signify the status of different members of Mesoamerican society.” Similar information has been documented by Fray Motolinia, Toribio de Benavente of Benavente, Spain as well. Arlen F. Chase, Diane Z. Elayne Zorn Chase, and Wendy Teeter. “Textiles and the Maya Archaeological Record: Gender, Power, and Status in Classic Period Caracol, Belize.” Ancient Mesoamerica 19, no. 1 (2008): 127-42.

- Nicholas J. Saunders, “Predators of Culture: Jaguar Symbolism and Mesoamerican Elites.” World Archaeology 26, no. 1 (1994): 104-17.

- Kathryn Klein and Getty Conservation Institute, eds. The Unbroken Thread: Conserving the Textile Traditions of Oaxaca (Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute, 1997), 130.

- Flowers of any kind often represent the presence of nature and fertility. Depending on the region of Mexico, legends of mystic flowers performing acts of wonder or providing families with children are often spoken and passed on orally from family to family. Chloë Sayer, Textiles from Mexico (Fabric Folios. London: British Museum, 2002), 18-20.

- “The ancient Mayas believed the underworld had nine levels and that the heavens had thirteen.” These myths would have been passed down from generation to generation, eventually being reinterpreted during colonization. “The supernatural is an integral part of daily experience. Threads join the body to nature and to the universe. Embroidery as a form of writing unleashes in its creator a flood of marvelous images associated with myths of incalculable age.” Orellana, and Weinberger, The Crafts of Mexico, 64.

- “V&A · Mexican Embroidery.”

- The importance of understanding where most of the whitework was practiced illuminates gender performance. “Male convents included among their members master embroiderers who made new vestments and repaired the old.” Paine, Paine, and Moss, Embroidered Textiles, 152.

- “The origins of blackwork can be found in Spanish embroidery before 1501, [as they] appear in England and many other countries before Catherine’s time. However, the association with Catherine led to the use of the term ‘Spanish work’ [and its’] popularity in England during this period.” Sarah-Marie Belcastro and Carolyn Yackel, eds. Making Mathematics with Needlework: Ten Papers and Ten Projects. (Wellesley, Mass: A K Peters, 2008), 1.

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Shawl (Rebozo) | Mexico.” Accessed January 26, 2023. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/21109.

- The information on rebozos could engulf a subject all to itself, as the style existed prior to the conquest, but flourished and transformed with cross-cultural influences from across the Pacific. These pieces doubled as a carrying cloth, both for goods and children. Paine and Paine, Embroidered Textiles, 175.

- Kirstin C. Erickson. “Las Colcheras: Spanish Colonial Embroidery and the Inscription of Heritage in Contemporary Northern New Mexico.” Journal of Folklore Research 52, no. 1 (2015): 1. https://doi.org/10.2979/jfolkrese.52.1.1, 2.

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Doña Rosa Solís y Menéndez | Embroidered Coverlet (Colcha) | Mexican.” Accessed January 26, 2023. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/13604.

- Patricia R. Anawalt, Davíd Carrasco, and Eduardo Matos Moctezuma. “Mesoamerican Indian Clothing: Survivals, Acculturation, and Beyond.” In Fanning the Sacred Flame: Mesoamerican Studies in Honor of H. B. Nicholson, edited by Matthew A. Boxt and Brian Dervin Dillon, 519-38 (University Press of Colorado, 2012), 526.

- Chloë Sayer, Arts and Crafts of Mexico (London: Thames and Hudson, 1990), 29.

- The study of symbolism in Mexican iconography depends on the region and the beliefs of the native people who existed prior to the conquest. In the Crafts of Mexico, “Ethnologists have the most complete understanding of the symbolic nature of folk art objects, which either have significance in their own right or partake of a larger religious whole. Weavers [and embroiderers] are people who use threads to represent their culture’s symbols in cloth, transforming external influences, foreign objects, and unknown materials, by appropriating them and integrating them into their culture and their textiles.” Orellana, Ruy Sánchez, and Weinberger, The Crafts of Mexico, 59-63.

- Klein and Getty Conservation Institute, The Unbroken Thread, 14.

- Frances F. Berdan, “Cotton in Aztec Mexico: Production, Distribution and Uses.” Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos 3, no. 2 (1987): 241.

- Orellana and Weinberger, The Crafts of Mexico, 63.Sayer, Arts and Crafts of Mexico, 32.

- Sayer, Arts and Crafts of Mexico, 32.