Essays

From Obedience to Rebellion: Embroidery and Feminine Identity in Late-Eighteenth to Early-Twentieth Century Britain

Alanna Campbell

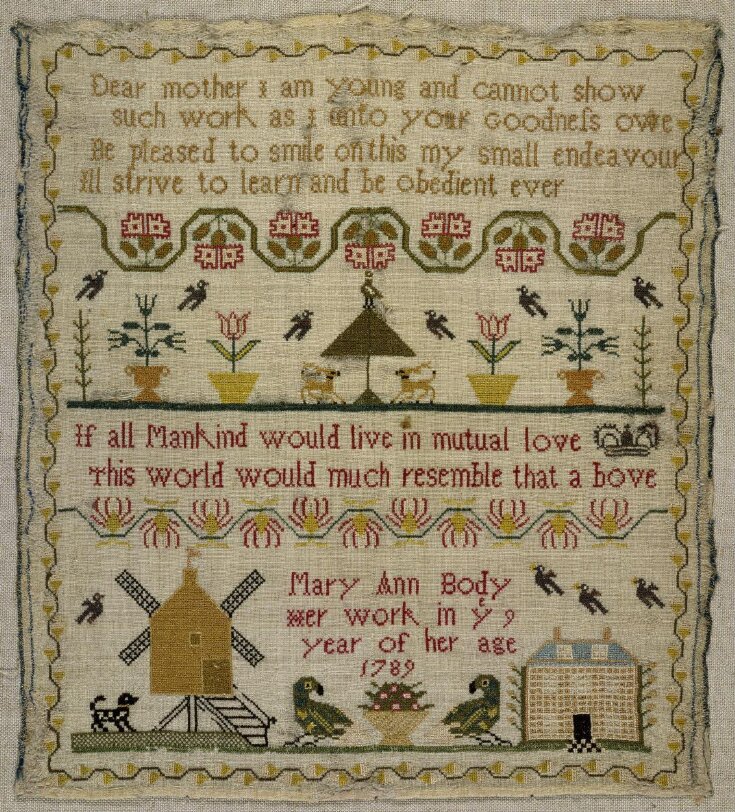

Fig. 1 Sampler, Mary Ann Body, 1789. Wool, embroidered with silk in cross stitch. Given by Frances M. Beach, Victoria and Albert Museum. T.292-1916.

“She is silent when she sews, silent for hours on end…she is silent and she – why not write it down the world that frightens me – she is thinking.” – Colette

The study of embroidery samplers in the late eighteenth to nineteenth century and the embroidered works of female designers in the nineteenth and early twentieth century demonstrates the profound presence needlework played in the lives of British women. As a form of education, domesticity, occupation, and community; embroidery and needlework were essential to the construction of female identities during this time. The connection between needlework and feminine identity in Britain is complex, and deeply tied with the consciousness of female purity in this era, an idealized and pastoral domestic image befitting the preservation of a subservient nation under God-given, monarchical rule. Roszika Parker describes this tension, stating that “the manner in which embroidery signifies both self-containment and submission is the key to understanding women’s relation to the art. Embroidery has provided a source of pleasure and power for women while being indissolubly linked to their powerlessness.”1

Writing on the healthy teaching and nurturing of young girls, published in late eighteenth and early nineteenth-century Britain, such as Maria Edgeworth’s Practical Education (1798), saw the practice of embroidery as a suitable skill for middle and upper-class girls. Embroidery taught patience while encoding the values of discipline and domestic obedience, indispensable to feminine virtue.2 By the mid-nineteenth century, industrialization across Britain had altered traditional craftsmanship, and, consequently, the accepted role of embroidery practice held in prior centuries. Through the consideration of female embroidery designers, such as May Morris, Phoebe Anna Traquair, Jessie Newbery, and Ann Macbeth (1875-1948), needlework as a practice, skill, and creative outlet becomes a means by which women can construct their careers and identities as female designers, subsequently forming a place for themselves within nineteenth-century British society.

Part I: Samplers in the Late Eighteenth to Mid-Nineteenth Century

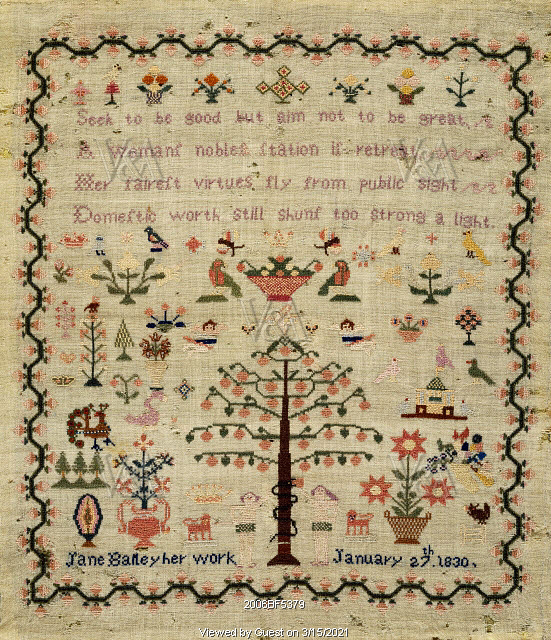

Fig. 2 Jane Bailey, Sampler, 1830. Embroidered woollen canvas with coloured silks, backed with crêpe. Given by Miss M. C. Sparrow, from the collection of Miss Marjory Bine Renshaw, Victoria and Albert Museum. T.321-1960.

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, young daughters from middle to upper-class British households were encouraged to pursue academic education as a foundation for their eventual roles as wives and mothers. A role in which they would be required to present themselves as suitable companions for their accomplished husbands, and teachers to their children.3 They would be taught by hired governesses or attend private schools for girls. For young British girls in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the process of repetitive needlework, as seen in historical samplers, was a tool for study and education, while simultaneously imposing docility and godly devotion. Needle and thread were also used in girls’ education to teach various, traditionally “masculine” subjects. Samplers from the Victoria and Albert Museum and Metropolitan Museum of Art collections demonstrate a study of geography, mathematics, and astronomy. However, samplers can also be identified as a form of personal expression, revealing many facets of the beliefs, relationships, and lives of girls and young women at this time, a record often difficult to grasp.

At this time, female identity in Britain was recognized as a girl’s ability to be of service to men, as daughters, wives, or mothers.4 Therefore, when considering embroidery’s influence on the construction of femininity during this period, we must acknowledge that to teach and practice needlework was to communicate and condition messages of servitude. Through the stitching of various scriptures, nature scenes, and blissful, domestic homesteads, young girls were cultivating the feminine identities by which they would be motivated to live, presenting themselves as obedient, patient, domesticated, and ultimately marriageable. Nevertheless, through the act of sampler making, and the practice of embroidery, these young girls were stitching themselves, perhaps fortuitously, into the fabric of history.

An embroidery sampler from 1789, stitched by Mary Ann Body at the age of nine (Fig. 1), demonstrates how embroidery practice intertwined with mother-daughter relationships in the eighteenth century. In simple brown silk on wool, Mary fastened a plea to her mother and adorned it with birds, deer, potted plants, and a variety of decorative framings, many of which are symmetrical. She placed a quaint home and windmill at the bottom of the sampler, along with her name, age, and year. The appearance of messages or promises addressed to girls’ parents in embroidery samplers of this period is not uncommon, and are early iterations of domestic obedience. It also establishes a hereditary connection between mother and daughter, a tradition of embroidery practice passed down through generations of women, within which a daughter can see herself in her mother (and vice versa).5

In many samplers, young girls also impress the moral narratives encoded in the act of needlework itself. A sampler made by Jane Bailey in 1830 demonstrates this tendency (Fig. 2). In neat, violet-stitched lettering, Jane described the place of women in Britain at this time, “Seek to be good but aim not to be great,” detailing the moralizing and feminine virtues she will be obliged to exhibit. Alongside this sentiment are visual signifiers that reiterate this message. At the center lies the Tree of Life, flanked by Adam and Eve, and two tiny angels. Eve appears to be reaching up to the coiling snake’s mouth, a metaphor for eternal sin. On either side we can also see a crown and two lions, surrounded by flowers, small birds, and farm animals, positioning the British monarchy as crucial to this idealized imagery.

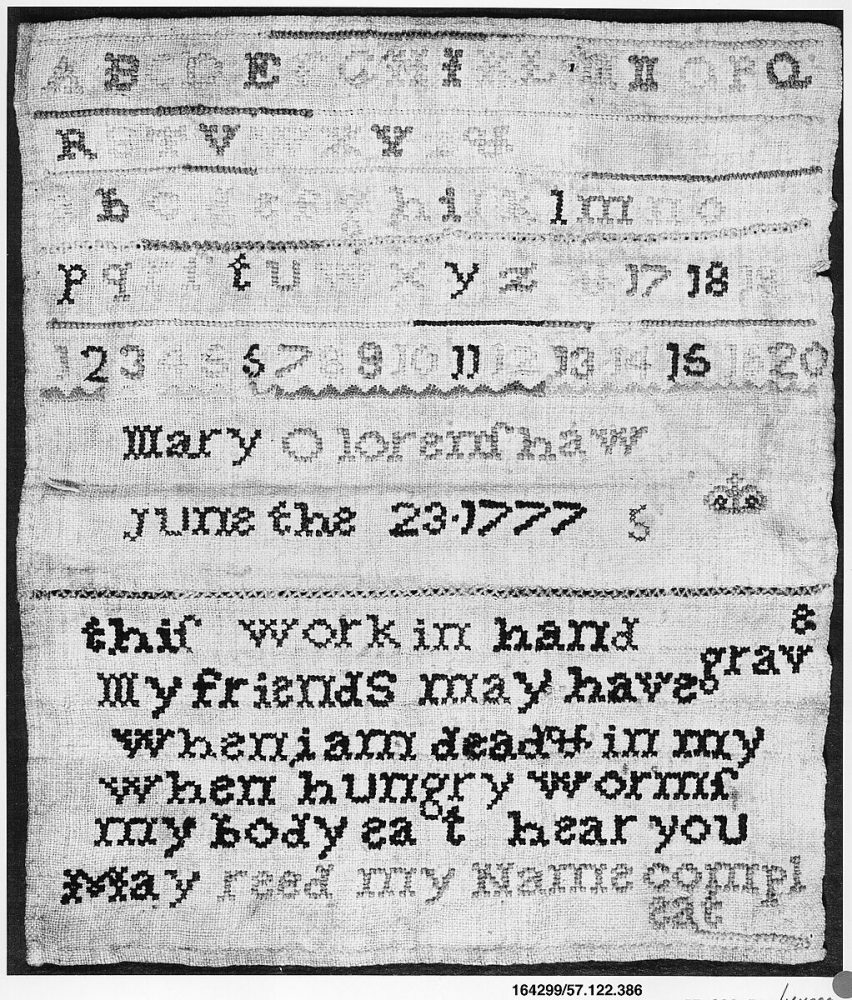

Fig. 3 Embroidered sampler, Mary Oloremshaw, 1777. Linen embroidered with silk thread, 8 7/8 x 7 1/2 in. (22.5 x 19.1 cm). Bequest of Mabel Herbert Harper, 1957, The Metropolitan Museum. 57.122.386.

References and contemplations of death also make an appearance in young girls’ samplers. Death’s presence as a subject is an expected result of the proliferation of God-fearing scriptures in educational sampler-making.6 In a sampler from 1777, young Mary Oloremshaw requests that upon her death said sampler be gifted to her friends, “[w]hen hungry worms my body eat hear you may reed my name compleat” (Fig. 3). The various spelling errors, and small “5” located in the center of the sampler, could suggest Mary’s age at the time of completion. Regardless of her exact age, the juvenile hand is evident, and the piece’s sentiments are haunting in their naïve candor. Acting almost as a last will and testament, Mary’s sampler demonstrates a widespread fear in eighteenth-century British society: death, or more observably, the death of children. Nearly two-thirds of all children died before the age of five in mid-eighteenth century Britain. The language of death is consequently not detached from the lives of children at this time. Mary’s sampler becomes imbued with an underlying melancholy, a sense of dread that comes inevitably with most objects created by young children during this era.

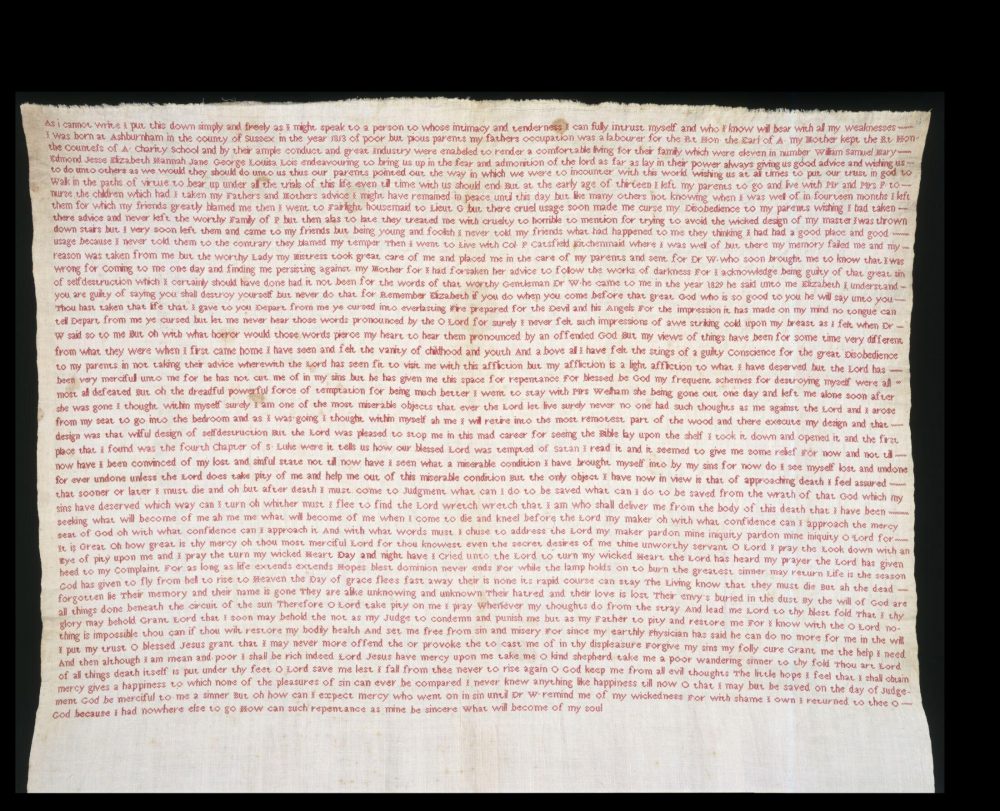

Fig. 4 Elizabeth Parker, Sampler, 1830. Linen, embroidered with red silk in cross stitch. Victoria and Albert Museum. T.6-1956.

One of the most unique, and evocative samplers is a piece by Elizabeth Parker from 1830 (Fig. 4). According to the sampler’s stitching, Elizabeth was born in 1813 in Ashburnham, county of Sussex, making her seventeen at the time of the sampler’s creation. In forty-six lines of red silk, Elizabeth recounts the past four years of her life. She begins by stating: “[a]s i cannot write I put this down simply and freely,” perhaps insinuating that she was never formally taught how to write, resulting in her decision to stitch this confession. Elizabeth details her family’s poverty, and her decision to leave her family at thirteen to work as a housemaid for a man identified as “Lieutenant G.” Elizabeth describes the “punishment for disobedience” she would endure from the Lieutenant, who at one point threw her down a flight of stairs. Scholars speculate that Elizabeth may have been sexually abused by the Lieutenant, although this is not something she discloses within the sampler.7 The rest of Elizabeth’s stitched profession is a plea to God, begging him to forgive her, as she admits feelings of intense shame have pushed her to a desire to commit suicide. She combines stirring, and desperate cries for help with recollected bible scripture, simultaneously sharing her intrinsic fear of death and the wrath of God, while maintaining hope and faith that she will one day be saved if she can surpass this deep pain, and “sin.”

The subject matter of young girls’ samplers in eighteenth and early nineteenth-century Britain facilitates a complex discussion, particularly within the awareness that said subjects are naturally oppressive, and continue to be utilized by women well into their adult lives. In her book, The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine (1984), Parker considers why young women and girls selected the subjects they did in their samplers, asking what they may have gained from “conformity to the feminine ideal, and how they were able to make meanings of their own while overtly living up to the oppressive stereotype.”8 The practice of needlework and the presence of embroidery samplers hold deep significance in the lives of girls, as pieces of spiritual and existential reflection, or tender sentiments.

As such, the creation of embroidery is entangled with a girl’s construction of self in Britain at this time. It is also quite notable that in many instances the stitching of embroidery samplers coincides with the onset of puberty in a young girl’s life. Here, in the often reflective and laborious stitched lettering of scriptures and moral coding, among cross-stitched pastel houses and growing flowers, are allusions to a girl’s virginal purity. Elizabeth Parker’s red stitching on plain linen is visually comparable to blood on cloth and materializes like a display of female shame. Within crooked, hand-stitched apologies and innocently held promises, young girls ask for divine forgiveness, almost, as if asking for forgiveness for simply existing. An act directly incongruous with the sampler’s coinciding proclamations, they are fragments that say: “I am here.”

Part II: Female Embroidery Designers in the Nineteenth to Early-Twentieth Century

From the end of the eighteenth century to the mid-nineteenth century, the role of the female embroiderer in Britain was questioned and transformed by the influence of several social and artistic movements.9 In 1792, Mary Wollstonecraft published her essay, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, marking early debates on the education and place of women within British society. These debates would become more pronounced by the end of the nineteenth century with the Suffragist Movement and appearance of the “New Woman.” The ideal woman became defined not only by her role in the domestic sphere, but her ability to “not only to win bread for [herself], but to use for the good of society, every gift bestowed on [her] by God.”10 The paradox of female embroidery practice during this period is exemplified in The Suffragette Handkerchief, embroidered by sixty-eight women in 1912. Each of the women individually stitched their signatures or initials into a handkerchief after many were imprisoned at Holloway Prison for their involvement in the window smashing demonstrations in London by the Women’s Social and Political Union.11 Whether it was due to ink and paper’s inherent ephemerality, or the effect of necessity, these women chose embroidery to communicate their message of dissent. On a handkerchief likely found in the pocket of one of these women, in an array of rainbow stitching, embroidery’s deeply held significance in the identities of British women is sewn.

Victorian Britain witnessed the popularization of Medievalism in arts and design,12 (including the study of “Opus Anglicanum” embroidery), which coincided with the Gothic Revival and early iterations of the Arts and Crafts Movement, fuelled by Design Reform initiatives. All of this coalesced in the development of “art needlework” as a practice, and thus the place of middle and upper-class women as artists, needleworkers, domestic craft makers, or above all, designers, was put into question. The prevalence of Medievalist models and the popularity of Opus Anglicanum in nineteenth-century Britain inflated the ideals of female nature as tied to embroidery craft.13 Parker describes this perception, stating that “Victorians saw the middle-ages as a time when embroidery and embroiderers were accorded the value which Victorian women themselves desired.”14 Was needlework a subjugating and restrictive practice for women that facilitated their solitude in domestic confinement? Or did women have a natural proclivity to needlework, which tied embroidery to the feminine, and therefore, the identities of women?15 What does it mean to be a woman in Victorian Britain, and how does embroidery practice play into this identity construction? The formation and imposition of a Victorian, feminine ideal is therefore crucial to understanding the nineteenth-century British woman.

The development of industrialization in Britain also altered the practice of embroidery, and the image of the self-contained, female embroiderer. Additionally, this period saw an increase in the production of printed material, which enabled women to publish their writing on the practice of embroidery and needlework. One of the most prominent proponents of “art needlework” was Lady Marian Alford (1817-1888), who published Needlework as Art in 1886. Alford was also a member of The Royal School of Art Needlework (R.S.A.N.)16 founded by Lady Victoria Welby (1837-1912) in 1872. R.S.A.N. was a leading educator in the art of hand embroidery. Across Britain, the formation of arts and design schools was essential to the nurturing of female education and design practice in the late nineteenth century. Within these establishments, fueled by desires to return to a pre-industrial landscape, the work of female embroiderers gained their place as “art” in British society. By discussing the works of female designers across Britain in the nineteenth century, we can observe how their individual embroidery practice (often one of many held design skills), enabled them to pursue careers as artists, designers, and educators.

May Morris

May Morris was born on March 25, 1862, to William and Jane Morris.17 May was raised among Pre-Raphaelites, Socialists, artists, and designers, fostering an early, deep appreciation for the arts, and nature. May was taught to embroider as a child by her mother and had a deep curiosity for the world, often funneled through drawing and writing. She studied at the National Art Training School before becoming manager of the Embroidery Department at her father’s company, Morris, Faulkner & Co. in 1885, at the mere age of twenty-three.18

As head of the department, May recruited embroiderers for the workroom at Kelmscott Manor. This included May’s friends, such as Lily Yeats (1866-1949. She also hired the fourteen-year-old Ellen Wright (n.d.). As employees of the department, the women received tuition from May, to educate themselves on the Morris embroidery style. She oversaw pricing and would liaise with clients, completed design work, took stock of the shop, fulfilled orders, and oversaw the quality of final products. The department was known for using a traditional design transfer technique, a time-consuming process that required transferring the design through outlines onto the fabric, rather than using pre-printed embroidery designs.19 In many of her early designs under Morris & Co., May was restricted to a distinct brand style, which led to many of the misattributions of her work as that of her father’s. May eventually left the department in 1896, the year of William Morris’s passing, and moved on to pursue independent arts and design projects, as well as her passion for teaching, and writing. This included working at the Royal School of Art Needlework and publishing her own theories in Decorative Needlework (1893).

From 1895-1900, May designed and embroidered two panels commissioned by an unknown source, titled “Spring and Summer” and “Autumn and Winter” respectively.20 In these works, May utilizes an array of stitches in colored silks and metal thread, including laid and couched work, French knots, running, long and short stitches, back stitches, split, satin stitches, and stem stitches.21 Although clearly inspired by her father’s design work, May exquisitely combined her own stylistic quality with intricate patterning and a detailed rendering of nature, including parakeets, growing flowers, blooming trees, and silk birds in the midst of flight. The use of dark, scrolling lettering, reminiscent of Medieval script, is a reminder of Medievalism’s influence on May’s work. These panels showcase May’s particular technical expertise as well as her devotion to capturing nature in her work.22

A cot quilt, titled The Homestead and the Forest, designed by May Morris, and embroidered by her mother, Jane Morris, in 1889-1890, once again demonstrates the role of embroidery in the relationships of mothers and daughters at this time. In this quilt, we can note the skilled use of many stitches, including the darning stitch, running stitch, stem stitch, satin stitch, herringbone stitch, trellis, and French knots.23 Created in anticipation of May’s wedding, the quilt is an observably collaborative, and sentimental project between May and her mother. This quilt was perhaps conceived in hopes of the eventual birth of a child, something that for May, would never come to pass.24 Bordering an encyclopedic display of animals are twelve quotes in several languages (including Farsi, Italian, and Latin) that express the importance of education, kindness, hard work, and fairness.25 Surrounding the peace of a domestic homestead lies a world of adventure waiting to be discovered. The quilt remained in May’s possession for the rest of her life, as one of her most personal and cherished creations.26

In 1909-1910, May traveled to North America on a lecture tour, sharing her knowledge of embroidery and textiles, as well as her own techniques. In 1907, she founded the Women’s Guild of Arts, which compensated and supported women working in the arts and crafts.27 Through teaching, writing, her foundation, and continued practice, May not only established her place within the history of design, as more than simply “William Morris’s daughter,” but also actively endeavored to better the lives of women in her community. This effort often took the form of uplifting women and their creative practice. Embroidery presented a means of occupation for May and a channel for female community within a male-dominated industry.

Jessie Newbery and Ann Macbeth

At the start of the Industrial Revolution, Glasgow’s proximity to the Clyde, and pre-existing textile industry facilitated an influx in factories, and thus, an exponential increase in population. The massive provision of art and design schools, galleries, and museums in Glasgow was an intentional endeavor to improve civic industry, and therefore, reduce the level of poverty, challenging the deep-rooted presence of alcoholism, unemployment, and mental health issues in the city. By the end of the nineteenth century, Glasgow would be recognized as the “Second City of the Empire.”28

The Glasgow School of Art was founded in 1845 as the Glasgow Government School of Design. Francis “Fra” Newbery, school director and Jessie’s husband, established the G.S.A. as ideologically aligned with Design Reform initiatives rippling across Britain, stating that “picture painting is for the few but beauty in the common surrounding of our daily lives is or should be an absolute necessity to many.”29 By 1850, the G.S.A. admitted women, many of whom were middle-class and seeking training for future work in the design industry, and in 1885, the acceptance of female students was established as a firm policy.30

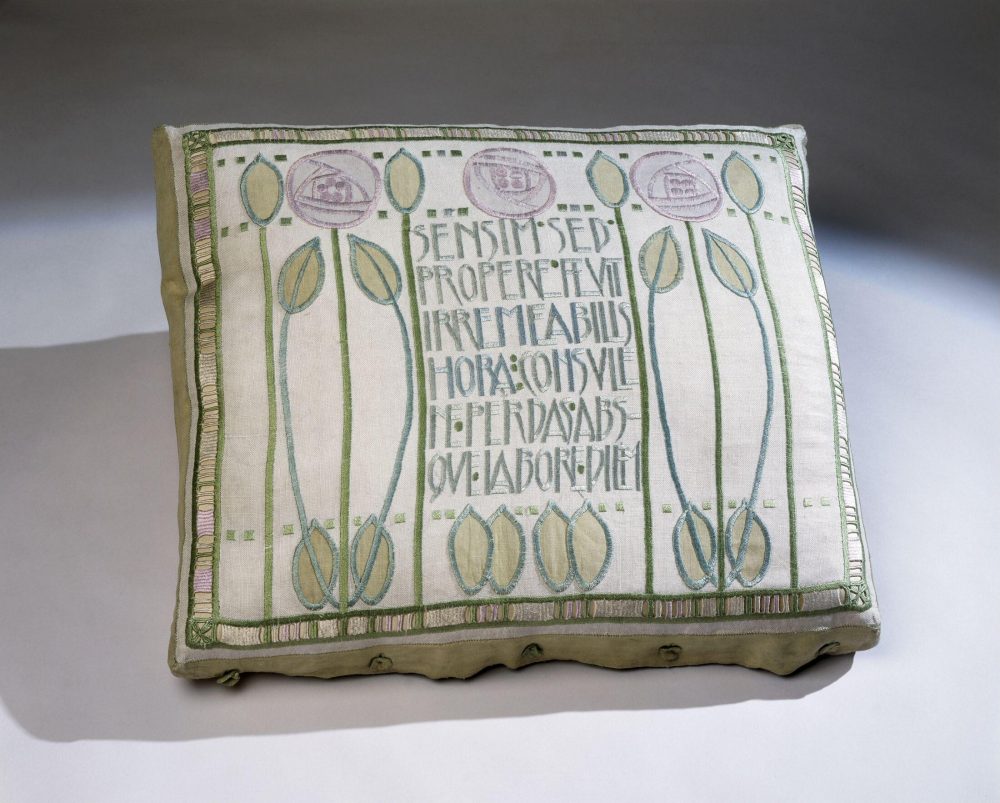

Fig. 5 Jessie Newbury, Cushion Cover, 1900. Embroidered linen with silks, linen appliqué. Given by Mrs M. M. Sturrock and Mrs Lang, Victoria and Albert Museum. T.69-1953.

Born in 1864, Jessie Newbery (née Rowat) enrolled in the Glasgow School of Art in 1884.31 She is recognized for her significant influence on the “Glasgow Style” (1895-1920) and the lettering design, heartleaf motif, and the iconic “Glasgow rose” popularized by the Mackintoshs.32 The “Glasgow Style,” which can be observed within Newbery’s embroidery work, is a notably “Glaswegian” design aesthetic, uniquely cultivated among G.S.A. students in the late-nineteenth century. The “Style” combines Art Nouveau qualities with industrial aesthetics, and utilizes Celtic, mythological, and fairy-tale imageries, capturing an often eerie and otherworldly quality in spindly forms, willowy women, and finger-pricking roses. Recalling images of the faeries and sprites the Scots so love to tell stories of. Jessie’s embroideries also capture her distinct linear style, often linked to her study of enamel, mosaic, and stained glass.33 This linear quality can be distinguished in her pillow cover from 1900 (Fig. 5), comprised of linen, applique, and colored silks, with satin stitch and needle weaving. The pillow cover showcases Jessie’s signature simplified lettering style, which she enjoyed juxtaposing against twisting plant forms. In a quote from Jessie, she stated that she enjoyed “the opposition of straight lines to curved; of horizontal to vertical,” and said she “especially aim[ed] at beautifully shaped spaces and [tried] to make them as important as the patterns.”34

In 1894, Jessie became head of the Embroidery Department at the school. In her classes, she was dedicated to fostering the individual artistic and creative merit of her (predominantly female) students, leading the department to international renown. She believed that embroidery teaching should be available to all classes and was an effective form of adornment on any manner of fabric.35 This conviction aligns with the department’s open access to citizens of Glasgow, which allowed many working-class women across the city to pursue lessons in embroidery and needlework. Here, we witness another instance where women were able to actively participate in their communities through the sharing of embroidery practice. She would continue to run the department on and off until her retirement in 1921,36 when her assistant instructress, and “most talented” former student, Ann Macbeth, would permanently take over as head.

Fig 6.1 Jessie Newbury, Collar, 1900. Silk ground, with appliqué of silk, embroidered in silk threads in satin stitch and couching, with glass bead and needle lace trimmings. Given in the name of the late Mrs R. A. Walter, Victoria & Albert Museum. CIRC.189-1953.

Jessie Newbery was also recognized for her style of dress, an expressive statement that aligned with the concurrent presence of the Artistic Dress Movement emerging across Europe.37 She abandoned the traditional corset for looser-fitting dresses and garments, which she embellished with embroidered belts and collars of her own making.38 A collar and belt set designed and embroidered by Jessie in 1900, utilizes similar rose and leaf motifs found in her other work (Fig. 6.1 & 6.2). By wearing handmade, embroidered accessories, she was able to present herself as visually aligned with arts and craft culture. The collar became an especially popular project among students, a tradition that Ann would continue in her own teachings. Within these handmade pieces of personal and unique adornment, we can see how women’s interest in embroidery, and their identity as designers in this period was reflected beyond just their daily occupations and was imbued in their clothing and dress.

Fig 6.2 Jessie Newbury, Belt, 1900. linen, appliqué, silk floss embroidery, glass and brass buttons. Victoria & Albert Museum. CIRC.190-1953.

Conclusion

The history of female embroidery practice in Britain is entwined with complex histories of domestic servitude. However, by the late nineteenth century, there appear numerous instances where British women were able to utilize their skills in embroidery to facilitate careers as designers. Beginning for many as an educational tool in elementary education, embroidery remained a touchstone in the lives of women from this era. Heather Pristash, Inez Schaechterle, and Sue Carter Wood describe needlework as a “vehicle through which women have constructed discourses of their own,” stating that “needlework does not function ‘as an alternative to discourse, but as a form of discourse’, that is, we think of the needle as the pen; it is a form of rhetoric with the potential to shape identity, build community, and prompt engagement with social action.”39 Embroidery was used by women to engage with philosophy and politics, to educate themselves and other women in their communities, and to understand their identities and femininity. It is through this awareness, and the study of female embroidery in the late eighteenth to early twentieth century Britain as a tool for communication, that the desires, dreams, fears, and values of girls and women can be revealed.

Alanna Campbell received a Bachelors of Illustration in 2019 and is currently a student in the MA program in the History of Design and Curatorial Studies offered jointly by Parsons School of Design and Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. She is also a Research Assistant and Teaching Assistant at Parsons. Alanna is interested in girlhood studies and in the role of material and visual culture in feminine identity construction with a focus on the eighteenth to twentieth centuries. Her research was featured in the 2022 Parsons School of Design, ADHT Festival Showcase.

NOTES

- Rozsika Parker, The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine (1984; repr., London: Bloomsbury, 2019), 11.

- Ariane Fennetaux, “Female Crafts: Women and Bricolage in Late Georgian Britain, 1750-1820,” Women and Things, 2009. Maria Edgeworth wrote that women “should rather be encouraged, by all means to cultivate those tastes that can attach them to their home and which can preserve them from the miseries of dissipation. Every sedentary occupation must be valuable to those who are to lead sedentary lives; and every art, however trifling in itself, which tends to enliven and embellish domestic life, must be advantageous, not only to the female sex, but to society in general. As far as accomplishments can contribute to all or any of these excellent purposes, they must be just objects of attention in early education.”

- Ellen Jordan, “’Making Good Wives and Mothers’? The Transformation of Middle-Class Girls’ Education in Nineteenth-Century Britain,” History of Education Quarterly, 31 (Cambridge University Press, 1991), 439-462.

- Jordan, “’ Making Good Wives and Mothers’? The Transformation of Middle-Class Girls’ Education in Nineteenth-Century Britain.”

- Fennetaux, “Female Crafts: Women and Bricolage in Late Georgian Britain, 1750-1820.”

- Parker, The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Josephine E. Butler, The Education and Employment of Women (London, 1868).

- “Hunger Strikes and Handkerchiefs,” RCP Museum, accessed December 16, 2022, https://history.rcplondon.ac.uk/blog/hunger-strikes-and-handkerchiefs.

- Anna M. Flinchbaugh, “A Stitch in Time: Art Needlework as a Vehicle for Expanding Professional and Creative Opportunities for 19th-Century Women” (Pratt Institute, 2021).

- Parker, The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine.

- Ibid, 31.

- Ibid.

- Flinchbaugh, “A Stitch in Time: Art Needlework as a Vehicle for Expanding Professional and Creative Opportunities for 19th-Century Women.”

- Anna Mason, Jan Marsh, Jenny Lister, Rowan Bain, and Hanne Faurby, May Morris: Arts and Crafts Designer, (Thames & Hudson, 2022).

- Mason et al., May Morris: Arts and Crafts Designer.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Mason et al., May Morris: Arts and Crafts Designer.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Mason et al., May Morris: Arts and Crafts Designer.

- Jude Burkhauser, Glasgow Girls: Women in Art and Design, 1880-1920(Edinburgh: Canongate Books, 1990).

- Burkhauser, Glasgow Girls: Women in Art and Design.

- Ibid.

- Elizabeth F. Arthur, “Glasgow School of Art Embroideries, 1894-1920,” The Journal of the Decorative Arts Society 1890-19404 (1980): 18–25.

- Burkhauser, Glasgow Girls: Women in Art and Design

- Arthur, “Glasgow School of Art Embroideries, 1894-1920.”

- Ibid.

- Arthur, “Glasgow School of Art Embroideries, 1894-1920.”

- Ibid.

- Burkhauser, Glasgow Girls: Women in Art and Design, 1880-1920.

- Arthur, “Glasgow School of Art Embroideries, 1894-1920.”

- Heather Pristash, Inez Schaechterle, and Sue Carter Wood, “Embroidery, and Sewing: The Needle as the Pen: Intentionality, Needlework, and the Production of Alternate Discourses of Power,” in Women and the Material Culture of Needlework and Textiles, 1750-1950(Routledge, 2016).