Interviews & Reviews Issue 5 2021

Curator Conversation: The Responsive Collecting Initiative at Cooper Hewitt

Charlotte von Hardenburgh

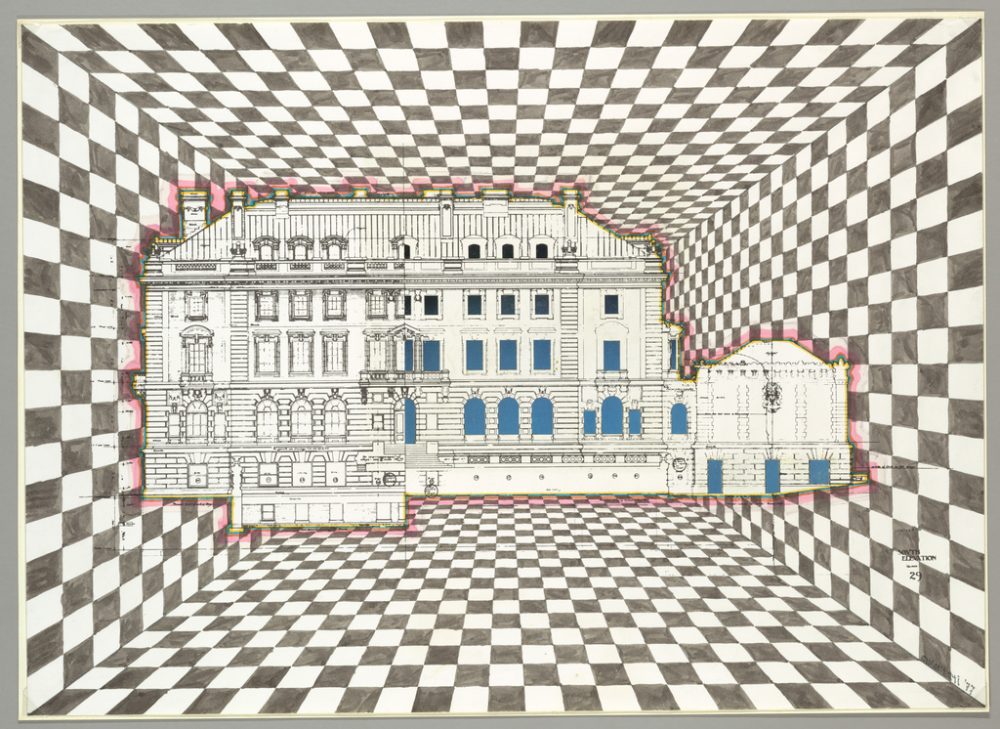

Drawing, Cooper-Hewitt embellishme; watercolor support: on colored paper; 1978-14-1. Courtesy of Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum.

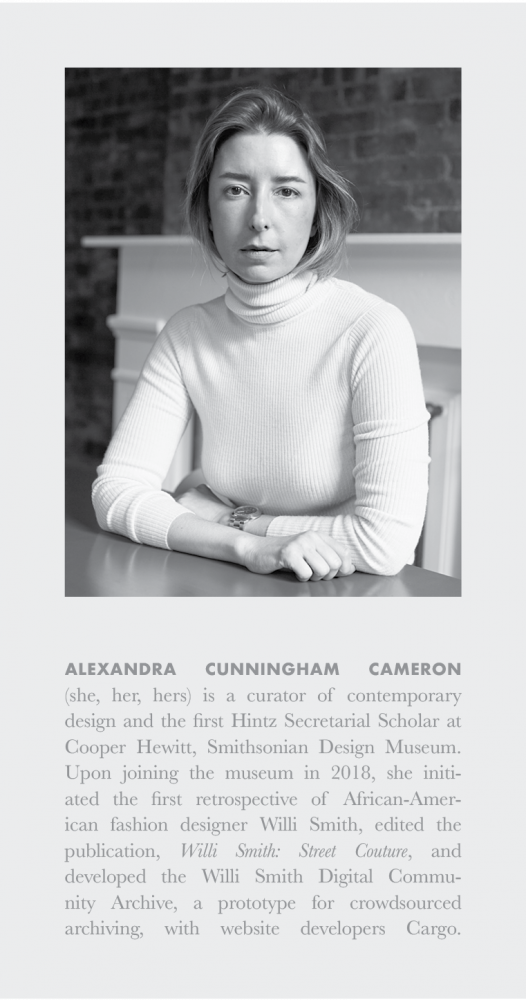

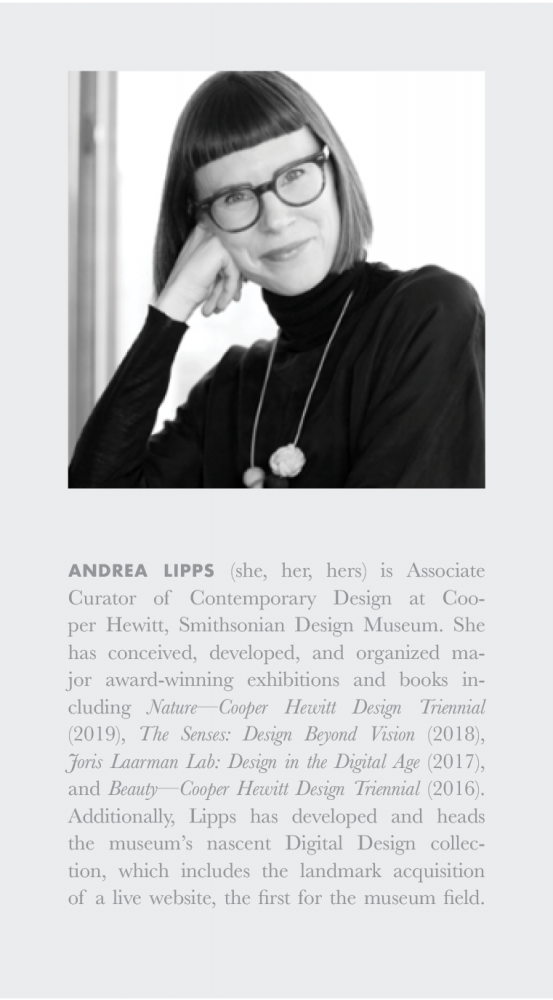

Andrea Lipps and Alexandra Cunningham Cameron are curators and co-chairs of Cooper Hewitt’s Responsive Collecting Initiative (RCI), which is a new effort to solicit, review, and add objects to the museum’s permanent collection. They have spent the past year developing a rigorous process to responsively collect designs of the moment. The initiative aims to tell design stories about the historic moments we are living through, including the COVID-19 pandemic, the movements for racial and social justice, the 2020 election, and the climate crisis. I met with both curators in January 2021 and again in April 2021 to discuss the initiative, focusing on the progress and process of RCI and what the future of curating and collecting looks like.

Charlotte von Hardenburgh: How did the Responsive Collecting Initiative (RCI) develop? Could you provide some context regarding its inception and your roles in its execution?

Alexandra Cunningham Cameron: In March 2020 the museum organized into different task forces to address the changing nature of the museum experience. Some of the people in the task forces were focused on operational aspects of the museum’s reopening, and another segment was focused on programmatic initiatives, such as collecting. Andrea and I were part of the Pandemic Response task force which had an evolving remit that led to a lot of conversations, not just about how Cooper Hewitt was responding to the pandemic but also to calls for racial, social, economic, and environmental justice especially given the protests for George Floyd which began after his death on May 25, 2020.

Alexandra Cunningham Cameron: In March 2020 the museum organized into different task forces to address the changing nature of the museum experience. Some of the people in the task forces were focused on operational aspects of the museum’s reopening, and another segment was focused on programmatic initiatives, such as collecting. Andrea and I were part of the Pandemic Response task force which had an evolving remit that led to a lot of conversations, not just about how Cooper Hewitt was responding to the pandemic but also to calls for racial, social, economic, and environmental justice especially given the protests for George Floyd which began after his death on May 25, 2020.

There was sort of a perfect storm of collaborative initiatives that allowed us to think about how we might collect around current events, to consider the ideal way to do that. We wanted the conversation to move beyond the curatorial teams and to include the feedback of other departments and individuals working within the museum. We decided to open the Responsive Collecting Initiative up to staff—including representatives from education, digital emerging media, the museum shop, visitor experience, conservation—to make the collecting process a broader conversation.

Everyone from these varied departments brought something very different to the exchange, and it became a new way to talk about the museum’s collecting mission, what the vision is for the collection, and how the collection can function as a document with and for our communities at the museum. We tried to organize the initiative as best as possible, to establish a process and to get new voices involved in collecting. Inevitably, we became comfortable with our plans often being foiled and with our timeline being undermined. What is most important is that we are attempting to do this together and widen the collecting conversation. The RCI wasn’t a marketing exercise by Cooper Hewitt, but a serious attempt to change the strategy for collecting contemporary design.

Andrea Lipps: When the pandemics hit, we quickly realized the museum lacked a mechanism that facilitated our collecting around historic events as they happen. We raised this in the task force that Alexandra just mentioned, where it sat as an idea until we took it upon ourselves to formalize the initiative with the two of us as co-chairs. Sometimes you have to start the process before getting permission. The initiative offers the museum an opportunity to conceptualize and try new approaches to the collecting process, from how works are identified to who participates in the conversations around proposed works for the collection. More than that, it provides a way to make the collecting process more transparent to those outside the curatorial departments.

Andrea Lipps: When the pandemics hit, we quickly realized the museum lacked a mechanism that facilitated our collecting around historic events as they happen. We raised this in the task force that Alexandra just mentioned, where it sat as an idea until we took it upon ourselves to formalize the initiative with the two of us as co-chairs. Sometimes you have to start the process before getting permission. The initiative offers the museum an opportunity to conceptualize and try new approaches to the collecting process, from how works are identified to who participates in the conversations around proposed works for the collection. More than that, it provides a way to make the collecting process more transparent to those outside the curatorial departments.

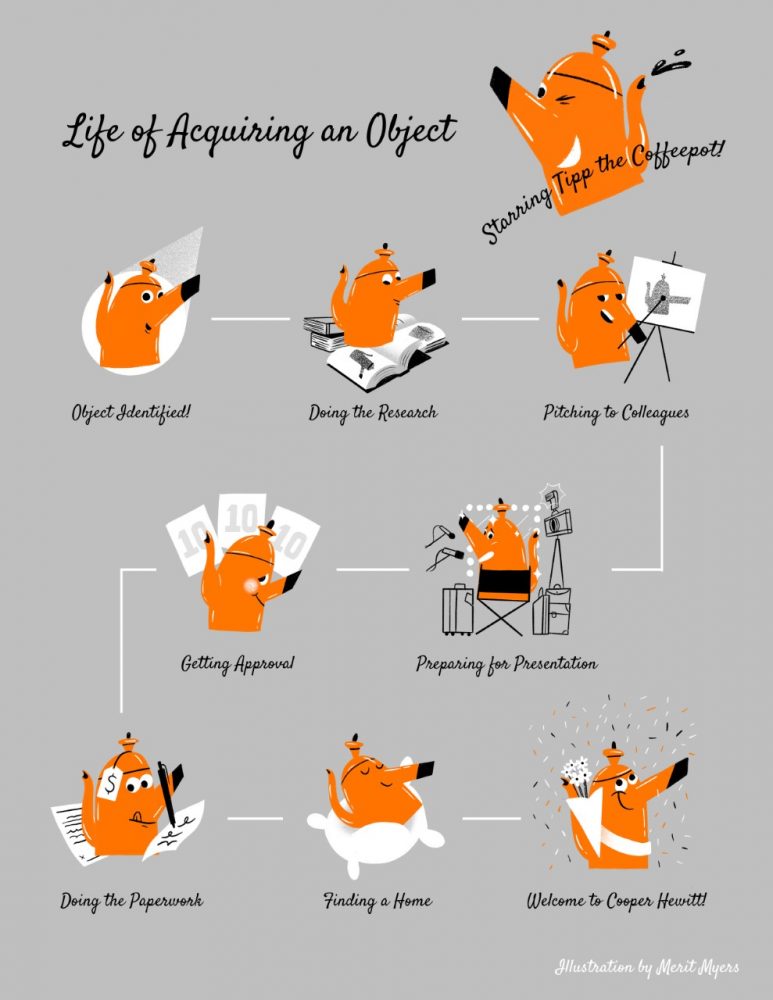

Among our efforts and in collaboration with our fellow curator Caitlin Condell, we generated the “Life of an Object” workflow that our colleague Merit Myers brilliantly illustrated (Fig. 1), to visualize the acquisitions process in an engaging, accessible and transparent way. We shared this as part of the introduction to RCI at a biweekly all-staff meeting. In order to open up the conversation to broader perspectives at the museum, we then organized and held an open call for all staff to nominate works to RCI to be considered for acquisition. (If we had the resources, we would ideally create a public open call.) We also formed an interdepartmental RCI committee that was responsible for reviewing the nominations and approving those that would move forward.

After we closed the nomination process on November 6, 2020, we gathered the RCI committee to begin reviewing the nominations. In the end there were, I think, almost 100 objects proposed. Initially we planned to review all of the submissions with the RCI committee, to get the approved nominations to their respective curatorial departments for preparation to be acquired [currently the museum’s four curatorial departments are: Drawings, Prints and Graphic Design; Product Design and Decorative Arts; Textiles; and Wallcoverings. A fifth collecting area—Digital—is quickly growing and will likely be established as the fifth curatorial department], and to present the first RCI works at our December 2020 Collections Committee meeting [laughs]. I’m laughing because we’re only presenting the first RCI works at the June [2021] Collections Committee meeting, which is a perfect example of our foiled timelines. This initiative is responsive, but not necessarily rapid.

Fig. 1 Merit Myers, Life of Acquiring an Object, (2020). Courtesy of Merit Myers, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum.

CvH: It seems then that RCI is not only about establishing a process for collecting designs of the moment but is also an initiative to refresh the collecting process, to make it more inclusive of Cooper Hewitt employees and the museum’s audience. Can you speak more about that?

ACC: Museums are held in public trust, yet typically only a very narrow segment of the public participates in museum development and business exercises. That process, which is specifically related to collections, is tightly choreographed by specialists—conservators, curators, various committees, and administration who make and approve acquisitions. Throughout the Smithsonian we wanted to have a meaningful conversation with the public about how museums can be of better service in meeting day-to-day life through programming and exhibitions, and also through acquisitions. We got very excited about the idea of opening up the acquisition process to broader staff within the museum.

It’s the first time in Cooper Hewitt’s history, to my knowledge—and I only started in 2018—that representatives from education, digital emerging media, the museum shop, visitor experience, conservation, and curatorial sat down together and had these conversations. We would like to expand to include security staff who are so well-acquainted with the objects that are displayed in the galleries, who see how the public engages with them, and hear their thoughts around interpreting these objects as well as protecting them.

AL: Actually, our security guards are the first line of conversation and dialogue with visitors in our galleries. What’s unique about some of the guards at Cooper Hewitt is that, beyond protecting the work itself, they proactively invite our visitors to engage with the objects on view. We would like to bring them into the RCI process so that they feel even more prepared to have conversations with museum visitors about these objects and the stories they tell.

ACC: Yes, and the RCI demonstrates a larger desire to open up these lines of communication as a way to incorporate audience feedback into our museum protocols and processes. Andrea and I are both really interested in those conversations, which have manifested through Andrea’s digital collecting and my development of a crowdsourced archive for the Willi Smith: Street Couture exhibition. The Willi Smith exhibition uses storytelling as a means of collaboration amongst scholars, historic figures, and enthusiasts whose lived experience with Willi Smith designs is something that excites them and us.

Responsive and rapid collecting initiatives are not just happening at Cooper Hewitt, but at other Smithsonian museums and in other museums around the world. Currently, there is tension between those who believe that museums should not engage in current events and those who think that museums have a responsibility to engage more actively or politically in the public sphere.

Many of the conversations that we’ve been having within the RCI Committee have been about how design has responded to current events but that this hasn’t been linked yet to how museums collect. Not only did we want to open up the conversation to as many staff members as possible, but we also wanted to have participation on the RCI committee rotate so that different people jump in and jump out allowing for fresh points of view and energy and ideas in each session.

CvH: In terms of objects, would you be able to talk about some of the current acquisitions and nominations? Do you have any that you’re particularly excited about or are you able to share the stories behind the objects?

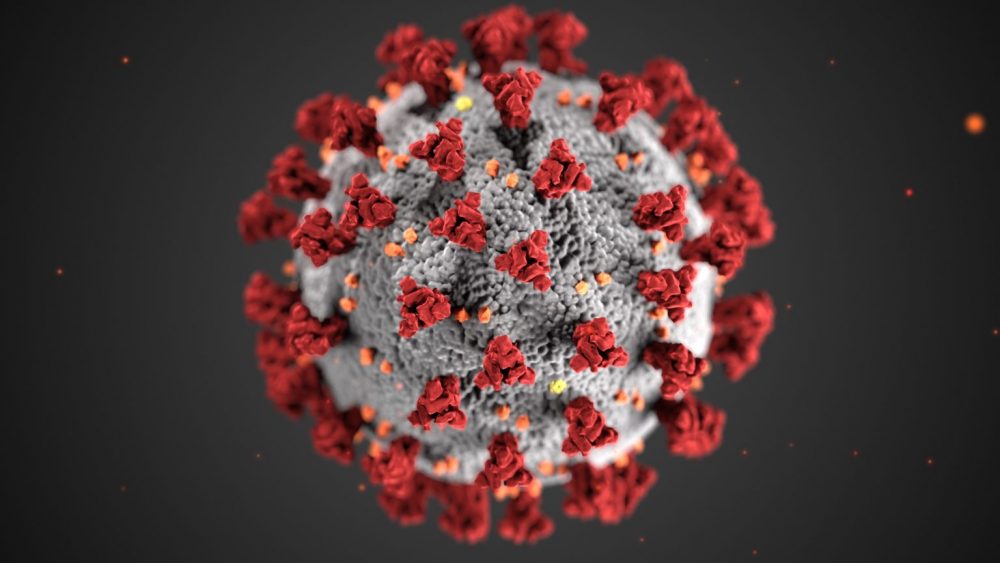

Fig. 2 Alissa Eckert and Dan Higgins, The Coronavirus medical illustration, 2020. Photo credit: Alissa Eckert, MSMI; Dan Higgins, MAMS, CDC.

AL: There are many objects we’re excited about but unfortunately we’re unable to specifically identify them if we haven’t yet reached out to the designers and acquired the work into our collection. A part of the collecting process is establishing a relationship with the designers and artists to not only negotiate the terms of a potential acquisition but also to learn more about their design intent and process. However, one work that I can speak to since I’ve been in touch with the designers and confirmed their participation in this process, is the CDC’s Coronavirus medical illustration (Fig. 2). This is the image that gave an identity, if you will, to the invisible virus we were fighting. It was illustrated by Alissa Eckert and Dan Higgins, medical illustrators at the CDC, and was made publicly available for download at the CDC’s Public Health Image Library in January 2020. We thus quickly saw the illustration everywhere—in newspapers, in broadcast news, on social media, in emails. It’s an example of how important design is in communicating quickly and effectively during a public health emergency.

Because the initial round of works identified them, and we are moving forward with all of the pieces that came from the first open call for nominations in fall 2020, it’s unsurprising that we have a large number of face masks—they’re such a ubiquitous part of our lives at this point in time.

We also have a number of digital works—everything ranging from the medical illustration of the virus (Fig. 2) to pieces of visual journalism from The New York Times. Also prevalent were digital files, whether files for posters that people could print out during the protests for the Black Lives Matter movement (June 2020) or instructions for how to make a face mask.

ACC: Yes, many designers are creating digital works that can somehow be printed out and constructed using resources that a person has at home.

CvH: How does Cooper Hewitt’s initiative differ from what other museums have developed in response to the pandemics?

ACC: It’s important to note that Cooper Hewitt’s RCI is not a rapid response collecting initiative, which is something that other museums are engaging in. I think Kieran Long at the V&A sort of popularized this activist idea, and many of our Smithsonian colleagues also have been on the ground at protests and during major historic events, discussing and cataloging and negotiating the acquisitions of particular works or ephemera. These are different processes than the RCI at Cooper Hewitt. The RCI weighs the contemporary context of the object, discusses it with the interdepartmental committee, and then puts it through our acquisition protocol (Fig. 1), which includes formal conversations with the designer or initiator of the work to understand the condition of acquisition.

AL: Sometimes curators and institutions in their eagerness to collect work overlook important conversations and considerations. We want to ensure that we engage thoughtfully with the artists and the designers of works we seek to collect.

CvH: Where are you currently in the acquisition process?

AL: The RCI Committee has had four meetings to review about 80 objects. We’re now (April 2021) reaching out to the curators to have more conversations about the objects approved to move forward, and we aim to present an initial selection at the June Collections Committee meeting.

ACC: The RCI has initiated a new process for collecting within the museum, and the committee is moving forward in a collaborative and thoughtful way… so it’s going slowly. Although there is a need to preserve some of the objects that are coming out of protests or COVID-19 experiments, we need time for conversations around how to collect and interpret them, for discussions with the designer or the donor. We appreciate the dialogue this initiative has incited, not just within the curatorial department but across all departments of the museum. These conversations within institutions can and should take time.

AL: There’s an intentionality to the process, which is important. We honor that and want to ensure the RCI isn’t just a knee-jerk reaction, but that its collaborative, open, and more transparent elements can be infused into our broader practice. We plan to issue another open call to staff for more nominations.

CvH: How has the collecting process of RCI affected collecting at large, in terms of the museum in general? Is there anything that you’re learning during this process that you’re going to apply in the future when it’s not a particular crisis that you’re collecting around?

AL: I think the type of discussions we’ve been having around the RCI acquisitions, about context and storytelling and narrative, will continue to permeate our practice and curatorial intent in collecting works. Works are being considered and evaluated in more unconventional ways, which enables us to be open to other modes of acquisition and reasons for acquiring works while still maintaining the rigor of our process. This may, in the end, help to push our thinking and impact on our constantly evolving practice.

ACC: And there will always be urgent global events that designers are critically involved in contributing to, in one way or another. We feel it’s important for the museum and its collection to always keep an eye on objects that respond to current events.

CvH: Do you have general themes or ideas in terms of how you would want curators to capture 2020 in an exhibition or in some sort of display practice?

ACC: Personally, my ideas about sharing these objects have been driven by new ways of storytelling and interpretation. Seemingly mundane objects, like a medical mask, take on completely different meanings based on context. They can become symbols of inequity or take on a political charge. Museums can collect and share the broad perspectives on everyday objects in a way that helps us better understand each other and our worlds.

The question: “How do we responsibly share these stories through objects?” has been really at the top of our minds. Is it through video? Is it through oral histories or recollections? What can we collect around the object to build up the context for how it was acquired, why and in what conditions? What does it look like when a design studio begins making masks instead of shoes? Who was there on the ground to do that? Who did they lose? We can bring to life the significance of some of these things through the people who were involved in producing or wearing or designing or appropriating them.

AL: Absolutely—our emphasis is on the quality of the objects we acquire rather than the quantity. We can create documentation to not only supplement but illuminate the works we collect, for example by interviewing an object’s designer or users, or gathering images of an object’s use. When we look ahead, the value of our efforts won’t be to have collected thirty masks but to have collected five that each represents a different story with oral histories from the people who used it. We’re not aiming to be encyclopedic; we need to wisely consider our limited resources, including staff time and storage space, that it takes to collect and care for work. In this way we hope to maximize the potential richness of storytelling for future generations about these objects and the period within which they were created.

ACC: That’s true. Often, in these conversations about museum display, it becomes a virtual versus physical dichotomy and you’re either on one side or the other, with strong opinions on both sides. What we’re discussing is something that cannot be manifested only physically in an effective way. There needs to be a virtual platform in order to effectively and broadly collect and share storytelling around objects. We really want to advocate for a type of complementary thinking around museum experience.

CvH: Aside from RCI, how are experiences relating to gender, race, and sexuality being integrated into what’s being exhibited? Who is putting these exhibitions together?

ACC: Institutions are under intense scrutiny right now and I believe that this is a tremendous opportunity. Projects like the RCI, or even the Willi Smith Community Archive, are intended to question the values of our institutions. That is a conversation that shouldn’t happen because of an eruption of identity politics but something that should be a constant and ongoing dialogue happening in institutions and with the broader public. Most critically, we all agree that representation matters and museum staff, curators, conservators, directors, administrators, need to include more people of color and to represent diverse experiences. That’s something that many museums have not yet been able to achieve but hopefully are working towards. I can’t say anything is more important than that at this point.

is a student in the History of Design and Curatorial Studies MA program offered jointly by Parsons School of Design and Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum and is also pursuing a graduate certificate in Gender and Sexuality Studies from The New School for Social Research. A fellow in the museum’s Textiles Department, she is currently working on her curatorial capstone for the upcoming exhibition Design, Texture, Color: Dorothy Liebes and the Textiles of the Modern Interior. She is Managing Editor and co-Editor-in-Chief of the fifth issue and first online version of Objective.