Objects

Can’t Stand the Heat: Heat Projections and Hot Comb Resistance on African American Women’s Hair 1860 – Present

Everette Hampton

The Hot Comb, a device used primarily by Black women to remove the textures natural to their hair, prompts questions about Eurocentric perspectives on beauty applied to Black women and the patriarchal attitudes of Black men in relation to Black women. This essay explores some of these ideas, past and present, and how this beauty tool enables, oppresses, and signifies. As part of my research into the tool, and throughout this essay, I reference a survey that I conducted titled “Hair Talks, Hair Bonds.” This survey follows the behavior and responses of 36 Black American women I questioned regarding hair care maintenance and management, hot tools, and especially the design of the Hot & Hotter Electrical Straightening Comb. It examines their relationship with a tool that utilizes heat and their adherence to projected beauty standards. Results from the survey may be found here. Anecdotal responses or short responses have been summarized using data visualization. The use of data visualization relates to W.E.B. Du Bois’ exhibition at the Paris 1900 Exposition, where he used charts to communicate African Americans’ successful contributions to the United States economy and society through design, education, enterprise, innovation, and invention.1 Throughout this paper, the terms “Black” and “White” are capitalized in accordance with the MacArthur Foundation’s and the Center for the Study of Social Policy’s (CSSP) commitments to anti-racism, the dismantling of racial neutrality or invisibility as it relates to Whiteness and their mindful acknowledgment of the United States’ historical relationship with systemic racism.2 Refer to both organizations’ explicit reasoning behind this decision, which supports the construction of this essay and the ways Whiteness has impacted the Black experience as it relates to Black material culture and design.

Fig. 1 Annie International Inc., Hot & Hotter Electrical Straightening Comb. https://www.amazon.com/Hot-Hotter-Electrical-Straightening-Double/dp/B08CS4PW8K.

OBJECT DESCRIPTION

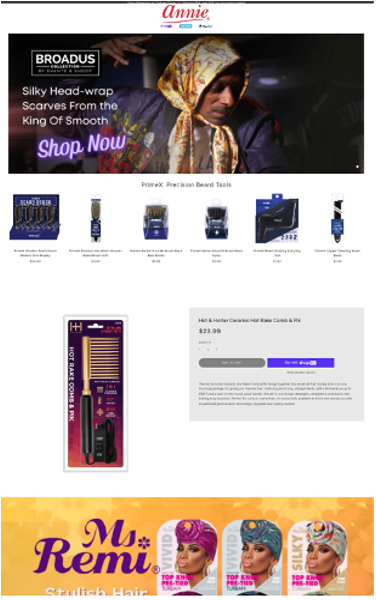

The Hot & Hotter Electrical Straightening Comb, packaged and advertised by “Annie International,” is positioned vertically, ready to be held. The comb’s base handle is solid, jet black, engraved in a cursive font with the company title, “Annie.” Connected to the comb’s handle is an electrical cord featuring a self-operative “On/Off” switch followed by a two-prong plug for insertion into an outlet. The “On/Off” switch is positioned and photographed upside-down with “On/Off” reading “No/FFO.” Attached to the handle is the gold-colored brass comb itself, which consists of twenty-five small, straight, evenly spaced teeth set close together to catch fine hairs. The straightening comb, in its entirety, is protectively encased in a thin, clear, molded plastic form to imitate glass casing. The hot comb is advertised on a rectangular, thick cardboard backing. The words “Straightening Comb” are positioned vertically on the far-left perimeter of the hot comb’s packaging, while on the far right of the image is a racially ambiguous woman with tan skin and a tempting, almost sinister smile. She models her jet-black, quaffed, and swept-straight hair. Below the model’s image, an additional advertisement states the features of the comb and its ability to reach 500-degree heat in Fahrenheit, an “Extremely Hot” temperature. Above the unknown model’s image, “Annie,” the brand name reads horizontally in red. To the left of “Annie” reads “Professional Use Only” in a smaller red font. Further to the left, in the top-left corner, reads “#5534 Electrical,” capitalized in green with a yellow background color. An organically shaped punched hole lies at the top of the packaging to showcase the product’s ability to be hung, suspended, and displayed for viewing. Annie International offers the Hot & Hotter Electrical Straightening Comb for a sale price of $17.99 (at the time of this writing in 2023), exclusive of taxes and fees.

The design and function of the Hot & Hotter Electrical Straightening Comb begs the question: Who can tolerate its extreme heat capacity, under what circumstances, and why would an individual tolerate its extreme heat? Why does hair, which is so biologically natural, need to be forcefully, electrically processed, and transitioned into a straight form? What does the straight-haired aesthetic achieve for consumers and those who view it? With no temperature regulation and only an “On/Off” switch, the consumer must choose to either endure 500-degree heat applied to the root of the hair shaft and raked to the ends of the hair strands or reject its heat entirely. Is the “On/Off” switch positioned and photographed upside-down a subliminal warning and disclaimer against the tool’s usage? Is 500-degree extreme heat the minimum requirement to achieve the quaffed, straight-swept look exhibited by the model? Is this look the most appealing style that can be achieved, and why is a straight-hair style the advertised style? The design suggests both experimentation and doubt, especially considering “Professional Use Only” presents itself in a smaller-sized font on the package in contrast to the rest of the text displayed on it. Standards are ambiguous, and the choice to use the appliance presented by the Hot & Hotter Electrical Straightening Comb seems to involve extreme risk and anxiety for its consumer.

HEAT GENERATION

Fig. 2 An Icall permanent wave machine from 1923 (left) and hair wound ready for tubular heaters in 1934 (right). Images courtesy of Louis Calvete.

While there is ambiguity surrounding the original inventor of the hot comb, Walter Sammons was the first African American man to patent the device in the United States on December 21, 1920. Therefore, it can be allowed that the intention in the hot comb’s invention and patent, at least in part, is derived from a perspective of and pressure from the African American experience at the time of the patent application’s submission. In contrast, the White Marcel iron’s invention by Marcel Grateau in 1872 in France is derived from a Eurocentric perspective and experience, considering Grateau’s intention to enhance feminine beauty for the consumption of men. Ironically, illustrations of other hot tools to curl White women’s hair can be set against demeaning caricatures of Black women’s hair. The juxtaposition of the permanent wave machine ads for White women set against the Pickaninny souvenir card realizes this idea (Fig. 2 and 3).

Fig. 3 Picaninny souvenir card. Copyright by E.C. Kropp Company, Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

https://www.pinterest.com/pin/488781365794361280/

The Afrofuturist artist Brandon Deener, in his 2021 painting Making Room for New Growth (Turquoise, Creme, Pink) (Fig. 4) gives a wholly contrasting view on the beauty standards for Black women in relation to Eurocentric views. Using spray paint, Deener illuminates Black pride by illustrating the density, texture, and thickness of Black hair on top of Annie hair combs in his painting. Each Annie comb in the painting shows signs of erosion, considering some of their fine teeth are missing, most likely due to thick hair resisting being combed and raked through to their ends. Black hair overpowers the tool used to detangle it, making the viewer question if the fine-toothed Annie combs’ purpose and design were truly intended and assigned to aid the consumer.

The same logic applies to the Hot & Hotter Electrical Straightening Comb and hot tools like it today. By plugging the electrical hot comb into an outlet and turning the power switch to its “On” setting, electric currents create heat that travels through to the heat conductor, the brass comb, where heat is stored and later transferred. Upon application of the hot comb onto the hair’s root, heat breaks protein and keratin bonds to straighten the curl or coil while at the same time, significant periods of heat exposure to the scalp may potentially result in scalded skin causing irritation, cuts, and burns. Consistent straightening, especially at unregulated temperatures or past hair’s heat threshold, has the potential to result in hair thinning, temporary or permanent hair loss, and hair damage. Emotionally and psychologically, low self-esteem and trauma result. Deener counters this practice in his painting by expressing Black hair’s effortless beauty in the artwork’s title, as it is resilient enough in its natural state without the application of heat to regenerate, grow, and lengthen on its own.

Fig. 4 Brandon Deener. Making Room For New Growth (Turquoise, Cream, Pink), 2021. Acrylic, spray paint, and oil on wood panel. 84 x 72 inches (213.36 x 182.88 cm). Courtesy of Simchowitz.

https://ocula.com/art-galleries/simchowitz/artworks/brandon-deener/making-room-for-new-growth-turquoise-cream-pink/

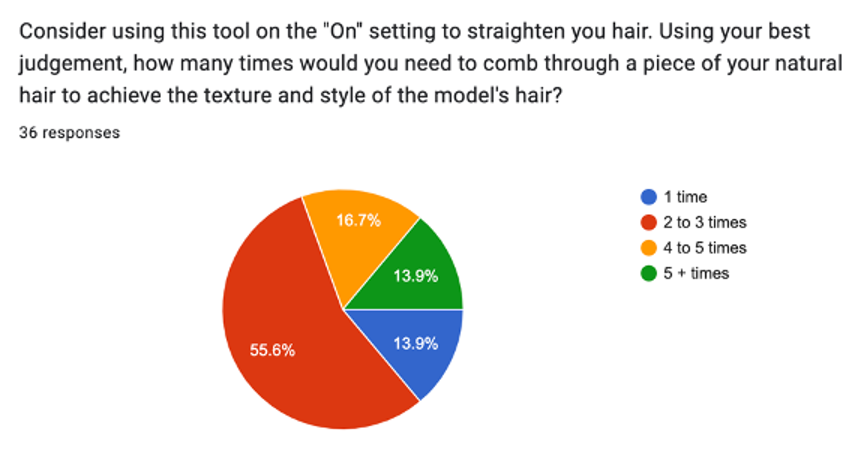

Eurocentric beauty standards channeled through the figurative Annie fine-toothed comb products live in the design of the tool rather than the hair that the tool performs against. Due to the fineness of the hot comb’s teeth, thick and coarse African American hair would be extremely difficult to comb through. On unmanipulated or blow-dried hair, the hot comb would hit a snag of hair or rake roughly through a hair section. It would also take the hot comb more than one pass through a hair section for African American women to achieve a straight, flowy, and silky texture. When 36 Black women were asked to study the Hot & Hotter Electrical Straightening Comb in the survey I conducted, 55.6 percent of the women shared that they believed it would take two to three passes while the hot tool was turned “On” to straighten their hair and achieve the straightness of the model’s hair as advertised on the Hot & Hotter Electrical Straightening Comb. Without the application of other hair products, it is typical and often necessary for the hot comb to rake through hair more times than once. However, the result may be what Deener painted and modeled for viewers. The intention of the hot comb’s design must be rooted in how it is used. The closeness of the Hot & Hotter Electrical Straightening Comb’s teeth suggests that to use the tool properly and achieve the advertised hairstyle; each section must be raked by the comb slowly from root to shaft to end, allowing the hair to hold highly concentrated amounts of heat. The tool is not one of efficiency but of caution. It is a cautionary tool marketed as “hair care,” thrusting the common phrase, “beauty is pain,” into commercial beauty strategy.

Fig. 5 Hair Talks, Hair Bonds Survey. “Consider using this tool on the ‘On’ setting to straighten your hair. Using your best judgment, how often would you need to comb through a piece of your natural hair to achieve the texture and style of the model’s hair?” April 28, 2023. Everette Hampton

Fig. 6 Hair Talks, Hair Bonds Survey. “Using your best judgment, how do you think the women’s hair was styled in the product image? Select any or all that apply?” April 28, 2023. Everette Hampton.

Fig. 7 Hair Talks, Hair Bonds Survey. “What is your natural hair’s heat threshold?” April 28, 2023. Everette Hampton.

According to my survey, two or three passes of the hot comb must be applied to a section of the hair and scalp to loosen kinks, curls, and coils into a “pin-straight” style. When the survey group was asked, “[u]sing your best judgment, how do you think the woman’s hair [in the Hot & Hotter Electrical Straightening Comb advertisement] was styled in the product image,” 86 percent of the women believed the model was either wearing a wig or weave extensions (Fig. 5-7). The consensus amongst the participants reveals that the style of straight hair pictured by the model is not realistic and that the marketing is an extreme extension of false advertisement and fantasy. Eurocentric beauty standards and the hot comb own the labor, performance, and determination required to achieve heat-straightened styles.

HEAT CONTROL: GENDER ISSUES AND THE HOT COMB

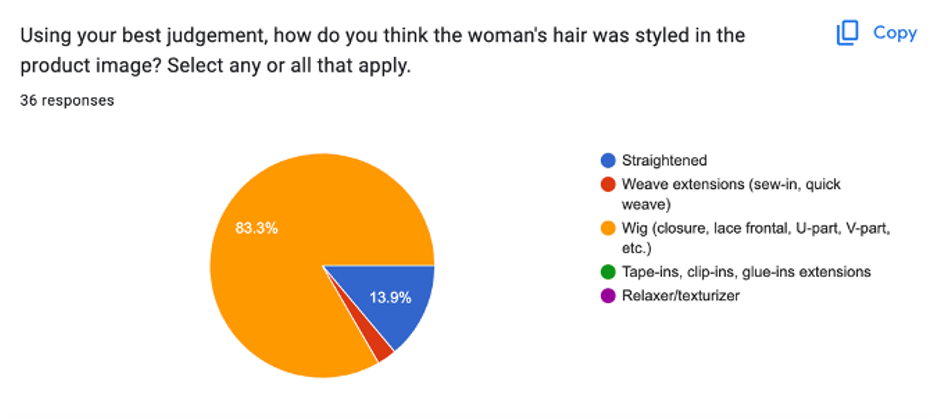

Walter Sammons’ hot comb’s production and distribution are contemporaneous to W.E.B. Du Bois’s writing and larger Civil Rights touchstones in the United States. Sammons’ hot comb design, for example, was patented seventeen years after the publication of Du Bois’ The Souls of Black Folks and patented a little over four months after the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified into the United States Constitution (Fig. 8). In 1920, Du Bois published “The Damnation of Women.”; this was at the onset of the Jazz Age, Machine Age, and the Harlem Renaissance when the likeness and exoticism of African materials and patterns were design inspiration and when the Black body and Black culture were realized and appropriated through art, design, and architecture from the chevron lines to Egyptomania to the erection of skyscrapers.3

Fig. 8 W.H. Sammons. Comb. Patent Application 1,362,823. Serial No. 372,611 Patented December 21, 1920

Walter Sammons’ invention can be connected to the rise of freed Black people’s access to public education legislation empowered by Black activism and tolerance from the Republican party during Reconstruction, which channeled opportunity for Black design and invention. Black men, more so than Black women, however, were able to formally project Black experiences, ideas, desires, theories, and vision into published writing and visual aids as a blueprint for a Black future marked by freedom and equality. The margin of equality, self-worth, and degree of separation between free Black men and free Black women was wide, given the imprint that slave owners left on generations during and succeeding antebellum slavery.4 Therefore, it is difficult to consider Black men actively representing the needs of Black women and consciously supporting forms of Black feminism during the period. Black feminist scholar Nneka D. Dennie describes the landscape of Black male feminism using W.E.B. Du Bois’ writing as it relates to the discourse surrounding gender and the Black experience. Dennie notes the following in response to W.E.B. Du Bois’ The Souls of Black Folks, published in 1903:

As Du Bois discusses the possibility of black people and white people living together in a peaceful and just society, he contends that “it will demand broadminded, upright men, both white and black, and in its final accomplishment American civilization will triumph.” In addition to portraying black men as responsible for determining the fate of the race, Du Bois normalizes “the Negro” as a masculine figure. He does not do so in a purely symbolic sense, but rather in order to present a model of African American education, self-consciousness, and leadership that revolves around black men. Because Du Bois universalizes African Americans as predominantly male, he is unable to analyze the nuanced lived experiences of black women, and he cannot fully theorize how their oppression is distinct from that of black men. It is evident from the rhetoric and content of Du Bois’s works that earlier in his career, he constructed a masculinist framework for overcoming racism.5

Beauty and power were projected from the Black male perspective yet derived or conditioned from the White male perspective, considering that the Black female experience was not considered or empathetically understood. Tolerance for pain was seen as tolerated by Black women, and, from a White colonial perspective, they were seen as target consumers in the product design field. “The Damnation of Women,” however, marked an evolution in W.E.B. Du Bois’ thinking as inclusive of anti-sexism, and what is now regarded as feminist theory puts Black women into the conversation around design, racial justice, and invention.

While “The Damnation of Women” uncovers a new layer of believed Africana female identity, Reiland Rabaka, Founder of the Center for African and Professor of African, African American, and Caribbean Studies, still critiques Du Bois’ writing.6 Rabaka argues that Du Bois develops a “control[ed] image” of the Black female identity that is palatable and self-sacrificing for Black women to be regarded as worthy matriarchs, spouses, and Christian members of society. The Black female identity remains in the possession of men rather than governed and owned by Black women. Reiland Rabaka argues that the disregard for African American women and the African American female experience in the early 1920s still exists today. A study conducted by the University of Virginia’s psychology department concluded that White participants believed “that the Black body is stronger than the White body through specific beliefs,” and “Black people’s nerve endings are less sensitive than White people’s nerve endings,” and that “Black people’s skin is thicker than White people’s skin.”7 It is significant to read this study along with my survey regarding heat tolerance as it applies to the application of hot tools to hair, revealing the average age of their first hair straightening to be as early as five years old. A fifth of the group revealed that they do not know how to care for their natural hair without using protective styles, hot tools, and hair salons/stylists.

Around the same time as Du Bois’ publishing of “The Damnation of Women,” Sammons’ patent acknowledges the necessity of heat tolerance as his patent incorporated a built-in and partially exposed thermometer according to lines 67 and 70 of his patent application. The preventative design feature is complemented with a heat-resistant handle listed in line 65 and label 13 of the patent.8 It is suggested that the hot comb was an attempt to assimilate Black women further and allow them to live in White society, to be as socially acceptable as possible by loosening the kink, coil, and curl of hair. This untightening of the kink, coil, and curl would enable Black women to secure employment, further domestication, and be visible and presentable to their White counterparts. Although a mask and mode of survival, the hot comb, as presented by Sammons, was a way of “untightening of the coil” in emulation of White standards; the make and model of the hot comb was a way to relieve some of the tension of enslavement and Jim Crow attitudes through assimilation to White standards of beauty. The hot comb was a solution that supposedly made life for women and the family more manageable and a way to unify the relationship between Black women and Black men as a partnership, considering slavery was a time when the Black family was separated by surname and physical distance without any guarantee of reunification.9

HEAT TRAINED

Although Sammons’ incorporation of a thermometer to regulate heat as applied to the hot comb was innovative at the time, removing a heat regulator in the Hot & Hotter Electrical Straightening Comb remains concerning today. The electrical hot comb’s replacement of the thermometer for an electrical “Off/On” switch suggests an assumption that the user is a professional hair stylist or expert at gauging the necessary temperature to achieve straight hair. Another assumption is that adding the new technology as an electrical component is too expensive or, ironically, too dangerous to manufacture. When asked, “What temperature or heat range do you apply to your natural hair,” 25 percent of surveyed Black women responded that they “do not know” what temperature of heat they personally apply to their hair when the straightening process is taking place. Similarly, 69 percent of Black women surveyed do not know their hair’s “heat threshold” or the amount of heat their hair is able to consume before becoming damaged. When asked whether they knew the temperature or heat range their hair stylist applied to their hair when receiving straightening services, almost 56 percent of the 36 surveyed Black women disclosed that they did not know. When asked about their communication and behavior to their stylist potentially surpassing personal heat thresholds that they, as the client felt, may feel be harmful or damaging, 33.3 percent of Black women answered they “Communicate to your hair stylist/salon that the heat setting and temperature hurts and needs to be decreased.” However, most Black women, or 58.4 percent of those surveyed, chose a form of endurance against pain; 30.6 percent disclosed that they signal a form of displeasing or uncomfortable behavior, while 27.8 percent of women “Ignore it and endure.” While this collection of responses does not confirm the pain tolerance or heat threshold of Black women against applied hot tools, it does confirm that Black women feel an intense amount of pain ranging from 100° Fahrenheit to 500° Fahrenheit.10 The endurance of pain equates to the neglect of pain and results in self-inflicted violence on the biology, psychology, beauty, and care of the Black female body. Nevertheless, demand for the hot comb still exists.

Endurance of pain has been taught and conditioned throughout the marketing of beauty products and tools. Before the hot comb was designed into an electrical mode more suitable for bathroom spaces, the hot comb was heated manually, and the process and practice of hair straightening took place in the home kitchen—if not in a beauty salon—making the hot comb a domestic tool for women and children to get their hair done.11 This is because the kitchen possesses a stove, oven, or hearth as the primary heating component and because it also possesses sinks as a water source to wash and moisturize hair, as well as tables as preparation sites to make a makeshift beauty salon in the kitchen. Hot combs could be heated on stoves (natural gas, coal-fired, or oil burning), which in the early twentieth century were called furnaces.12 While furnaces offered a significant heat source for hot combs to operate, heat was difficult to regulate, considering it was not until about 1915 that furnaces were designed with thermostats or temperature knobs or dials. Decades later, lack of heat regulation transferred to the invention of the Ceramic Heating Stove, a small electric stove that allowed mechanical hot tools to be kept hot up to 825° degrees Fahrenheit with the flick of an “On/Off” switch similar, if not identical, to the electrical “On/Off” switch featured on the Annie Hot & Hotter Electrical Straightening Comb. Inventiveness and progression of preventative care were limited based on the intention of the product’s maker, inventor, or manufacturer.

Sammons’ patent of the hot comb, therefore, not only allowed Black women and children to assimilate into White society but also helped propel women from the domestic interior to entrepreneurial spaces. In the 1920s and 1930s, programs for beauty systems such as Apex, Poro, and Walker created “Depression-proof” educational opportunities and sales representative jobs specifically for African American women to take advantage of the African-American-owned beauty industry.13 Yet, from the consumer’s end, it was difficult to keep up with the rising value and price of the African American beauty industry. Another form of pressure was applied to the evolving identity of African American women.

African American beauty professionals embodied the contradictions their business presented within black communities. On the one hand, they were businesswomen who wanted to make money, who shared the consumerist ethos that beauty could be bought, and who sincerely believed that the products and services they provided helped black women. On the other hand, in promoting beauty culture, these women faced challenges from within African American society even as they fought discrimination and racism outside it… Selling commercialized beauty culture to African American women was problematic on many levels. The products and services were expensive for most working-class black women, even though the profit margins of most African American beauty entrepreneurs remained narrow.14

Fig. 9 Ebony magazine, May 1964, Page 196, Ever-Perm by Helene Curtis advertisement.

John J. Johnson, founder of Johnson Publishing Company, added to the pressure. In November 1945, Johnson founded the publication and distribution of Ebony magazine. Although a pillar and source of African American culture, like most magazines, Ebony magazine offered a large series of advertisements rather than editorial slots, articles, columns, and news digest. Much of the advertising space was dedicated to beauty advertisements. Jobs existed for African American women in the beauty industry, whether as beauty ambassadors, beauticians, homemakers, inventors, models, sales representatives, socialites, or writers, especially considering the influence of Madam C.J. Walker and Annie Malone as models of successful entrepreneurs, inventors, and philanthropists.15 Black female inventors and entrepreneurs also created new employment opportunities. Black women-led organizations, including Black Ladies societies, for example, established debutante cotillions (coming-of-age ceremonies for Black female youth), which in turn influenced lower-class and middle-class Black women; straight hairstyles became redefined as a symbol of modernity rather than as an emulation of White beauty standards.16

Fig. 10 Ebony magazine, June 1966, Page 59, Ultra Sheen creme satin-pres. advertisement.

While Ebony did champion advertisements warning of the use of straighteners, chemical treatments replaced actual advertisements for mechanical and electrical tools. Hair and beauty advertisements featuring racially ambiguous, light-skinned women as symbols of high society were an alluring marketing tactic. However, the allure of the product advertisements was in their physical size, typography, and messaging.17 Advertisements for relaxers and chemical perms graced the pages of Ebony as less harsh alternatives to heat tools and the possibility of maintaining effortless beauty over longer periods of time.18 Hair creams were advertised in French spellings to add a Eurocentric, luxurious flair to the products’ brand identity (Fig. 10). Products packaged into small bottles or tubs made beauty seem more convenient and attainable. However, even using over-the-counter hair chemical treatments and relaxers, Black hair still needed to be blow-dried, straightened, and styled with heat once the permanent chemical cream was rinsed from the hair. The damage to natural Black hair was extended, and the form of naturally curly, coily, and kinky hair was erased through a compound of chemical and mechanical heat manipulations.

HEAT RESISTANCE AND RESURGENCE

The Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s served as a catalyst to resist the practice of using heat against Black hair when Kwame Brathwaite coined the “Black is Beautiful” movement. Built-up tension and anger regarding systematic oppression and racism were expressed outwardly through protests and direct courses of action rather than passive acts of racialized assimilation. Hairstyles such as Afros and wearing berets became iconographic symbols of a Black revolution and solidarity as they were and still are.19 Metaphorically, heat, in relation to hair, was discarded for the freedom of natural hair to breathe. The movement influenced Black culture to reclaim ownership of the Black identity and beauty standards. There were pageant productions such as Harlem’s Miss Natural Beauty Standard and protests against White hair establishments in Harlem such as Wigs Parisian. These were led by the African Nationalist Pioneer Movement and the African Jazz Art Society’s Grandassa model troupe, who only wore afros as a representation of modernity.20 The reclamation of beauty standards within the Black community was prevalent considering that in a 1972 study, it was reported that 90 percent of young men and 40 percent of young women in St. Louis, Missouri sported their natural kinks – progress from the 1950s through 1960s.21 This form of resistance aided and motivated political progress for the Black community, including the signing of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the creation of the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, and the filing of Jenkins v. Blue Cross Mutual Hospital Insurance, which produced Title VII of the Civil Rights Act to allow workers to wear afros in the workplace.22 The C.R.O.W.N. Act of 2019 formally stamped the Natural Hair Movement into American history, making discrimination against naturally styled and textured hair prohibited by California law (the C.R.O.W.N. Act of 2019 is an extension of a bill called the CROWN Act of 2022).23 This bill is timely considering that out of all those I surveyed, none of the Black women I surveyed preferred to wear their hair “straightened”; most Black women preferred to wear their hair in a “braided state” (meaning their natural hair was manipulated by hand and without the application of “High” heat from a blow-dryer). Out of those surveyed, over half disclosed that they would not purchase the Hot & Hotter Electrical Straightening Comb today. Despite the small sample size of the surveyed group, these results correlate with the contemporaneous ongoing Natural Hair Movement.

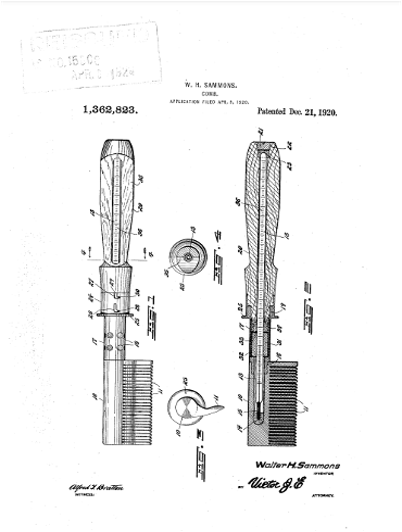

Fig. 11 Annieinc.com Home Landing Page, Annie International Inc., 2023

According to LinkedIn and their website, Annie International, the Hot & Hotter Electrical Straightening Comb’s manufacturer, is a beauty product supplier owned and operated out of North Wales, Pennsylvania, and not a company specializing in the haircare of Black hair. However, the company markets most of its products through Black beauty campaigns, imagery, models, and cultural products “to expand its product lines to match the latest beauty trends seen around the world in cosmetics, bath, personal care, hair and nail coloring, and electric styling tools” (Fig. 11).24 On the Annieinc.com website, an updated model of the Hot & Hotter Electric Straightening Comb featuring wider teeth emulates the commonly used wide-tooth comb for natural hair care (the Hot & Hotter Ceramic Hot Rake & Pic is offered for the price of $23.99).25 Product marketing is absent in the racially ambiguous model featured in the Hot & Hotter Electrical Straightening Comb product package. However, the product name insinuates a natural aesthetic by adopting the words “ceramic” and “rake” – all materials that reinforce the idea of handicraft, creation, and labor. The design continues to omit a temperature dial or heat regulator, and the electrical cord and “On/Off” switch remain. Annie International, owned and operated by Kevin Shinn, a non-Black person, confirms his and the company’s interest in the exploitation of Black cultural beauty products for financial gain, which is demonstrated in the company’s “About Us” page, which reads “…These innovative products continue to fuel the company’s steady climb and measured growth” while channeling hair product advertisements with 1990s famous Hip-Hop artist, Snoop Dogg, adorned in a hair scarf and allusions to National Pan-Hellenic Council (Black Greek Letter Organizations) members and culture to leverage back-to-school sales.26

The strength of Black activism and socio-political resistance must be applied to the commercial consumer space. Increased investment in science, research, and beauty products may benefit a sustainable Black future where ownership over the Black identity is freely defined by and for Black people and Black women especially. It may afford a future where Black people do not pit themselves against each other in response to any necessity to uphold Whiteness or Eurocentrism. It may afford an unwavering kinship among Black women and not pit Black women and Black men against each other, repeating a cycle of oppression that develops around, inside, and against the Black body. Examples of this exist through privately held Black female-owned businesses such as Pattern, Sienna Naturals, Tgin, Alikay, and Eden Body Works, which are more focused on building natural hair care products that move away from machinery, hot tools, and electrical elements. It also exists through the establishment of more Black female-owned wig companies and braiding hair providers to establish more access to protective styles that shield Black hair from heat and other harmful products and elements. However, resistance may be better served by Black women joining together to invest in the natural hair care industry, considering that there is strength and power in numbers.

CONCLUSION

Aside from the advancement of the hot comb as an electrical tool and its reimaging as a hairbrush straightener, its design and model have rarely been updated or reformed to reinforce “hair care” as a Black beauty standard. Few man-made haircare instruments offer protection against heat and manage heat for the range of hair textures that Black women possess. Considering newer, digital versions of the hot comb with heat gauges are available to consumers and professionals, why aren’t tools like Annie Hot & Hotter Electrical Straightening Comb discontinued? Is it because those who continue to produce hot tools truly believe the market exists, or is it because those who produce them do not truly know the Black female buyer? These questions lead me to question how systems can be developed to generate investment in the beauty industry for Black females. Design activism and empowerment for Black American women are also necessary to encourage investment in the manufacture, supply chain, marketing, and distribution of more products and tools for Black women, by Black women.

The modern and contemporary Black American woman does not only take pride in her hair simply for its strength and ability to be manipulated into various shapes and forms but also because of her ability to preserve ownership of what is hers as beautiful. It cannot be denied that some Black American women continue to choose to apply heat to their natural hair, whether due to Eurocentric projections of beauty, the desire to tame the curl for “efficiency” and “manageability,” or simply because of preference. However, resistance against Eurocentric beauty standards and assimilation practices begins with an unwavering grounding in choice and freedom and a sense of Afrocentric theory, thought, and pride. The protection of hair, the kinship bound by shared hair experiences, and the preservation of hair in its natural state require a significant exertion of heat and energy. Practiced with intention and care, these values are extremely rewarding, offering grounding, growth, and fortitude to the Black body, mind, and spirit. Hair care and heat management are a part of the life’s work of every Black woman and man. It is a practice that successive generations will adopt and form healthy associations with as long as the Black community chooses to remove the Eurocentric, patriarchal gaze and replace it with a championed Black aesthetic

Everette Hampton is a student in History of Design and Curatorial Studies at Parsons School of Design. Her interest and studies focus on race and material culture as it relates to African American and African Diasporic experiences encompassing the nineteenth century through the present. Everette received her Bachelors of Business Administration in International Business at Howard University with a concentration in Emerging Markets.

- Deconstructing Power: W.E.B. Du Bois at the 1900 World’s Fair (2022), Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York. 9 December 2022 – 29 May 2023.

- Jessica Pika, “Recognizing Race in Language: Why We Capitalize ‘Black’ and ‘White,’” Center for the Study of Social Policy, March 31, 2021, https://cssp.org/2020/03/recognizing-race-in-language-why-we-capitalize-black-and-white/. Additional justification of the capitalization of Black and White may be read on the MacArthur Foundation’s website: Kristen Mack, John Palfrey, “Capitalizing Black and White: Grammatical Justice and Equity,” MacArthur Foundation, n.d., https://www.macfound.org/press/perspectives/capitalizing-black-and-white-grammatical-justice-and-equity.

- Mabel Wilson, “Black Bodies/White Cities: Le Corbusier in Harlem,” ANY: Architecture New York, no. 16 (1996): 35–39. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41796597.

- William Edward Burghardt Du Bois, The Negro American Family: Report of a Social Study made Principally by the College Classes of 1909 & 1910 of Atlanta University, no. 13, (Atlanta, GA: Atlanta University Press, 1908): 1-41.

- Nneka D. Dennie, “Black Male Feminism and the Evolution of Du Boisian Thought, 1903–1920,” Palimpsest: A Journal on Women, Gender, and the Black International 9, no. 1 (2020): 1-27, doi:10.1353/pal.2020.0009.

- Reiland Rabaka, “W.E.B. Du Bois and ‘The Damnation of Women’: An Essay on Africana Anti-Sexist Critical Social Theory,” Journal of African American Studies7, no. 2 (2003): 37–60. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41819019.

- Kelly M. Hoffman, Sophie Trawalter, Jordan R. Axt, and M. Norman Oliver, “Racial Bias in Pain Assessment and Treatment Recommendations, and False Beliefs about Biological Differences between Blacks and Whites,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 113, no. 16 (2016): 4296–4301. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26469319.

- Walter H. Sammons, “W.H. Sammons. Comb,” United States Patent 1,362,823, filed April 9, 1920, and issued December 21, 1920.

- Yvonne R. Bell, Cathy L. Bouie, and Joseph A. Baldwin, “Afrocentric Cultural Consciousness and African- American Male-Female Relationships,” Journal of Black Studies 21, no. 2 (1990): 162–89. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2784472.

- Everette Hampton, loc. Cit.

- Lanita Jacobs-Huey, “Negotiating Expert and Novice Identities through Client-Stylist Interactions,” in From the Kitchen to the Parlor: Language and Becoming in African American Women’s Hair Care: Studies in Language and Gender (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2006), 18–21.

- Cherie Preville, “The 1920s: Ushering in the Modern Age of Heating,” ACHRNews online, BNP Media, published November 5, 2001, https://www.achrnews.com/articles/87034-the-1920s-ushering-in-the-modern-age-of-heating.

- Kathy Peiss, ” Making Up, Making Over: Cosmetics, Consumer Culture, and Women’s Identity” in The Sex of Things: Gender and Consumption in Historical Perspective edited by Victoria de Grazia (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996), 311-336.https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520916777-016.

- Susannah Walker, “‘Everyone Admires the Woman Who Has Beautiful Hair’: Mediating African American Beauty Standards in the 1920s and 1930s,” in Style and Status: Selling Beauty to African American Women, 1920-1975 (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2007), 47–84, http://www.jstor.org/stable/

- Ibid, 48.

- Tracey Owens Patton, “Hey Girl, Am I More than My Hair?: African American Women and Their Struggles with Beauty, Body Image, and Hair,” NWSA Journal 18, no. 2 (2006): 24–51, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4317206.

- Jerrika M. Anderson Edwards, “The Beauty Standard Trade-Off: How Ebony, Essence, and Jet Magazine Represent African American/Black Female Beauty in Advertising in 1968, 1988, and 2008,” (BA Thesis, Scripps College, 2013), 286, https://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/286.

- Ernest M. Mayes, “Chapter 5: As Soft as Straight Gets: African American Women and Mainstream Beauty Standards in Haircare Advertising,” Counterpoints 54 (1997): 85–108. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42975205.

- Chanté Griffin, “How Natural Black Hair at Work Became a Civil Rights Issue,” JSTOR Daily, last modified July 3, 2019, https://daily.jstor.org/how-natural-black-hair-at-work-became-a-civil-rights-issue/.

- Tanisha C. Ford, “HARLEM’S ‘NATURAL SOUL’: Selling Black Beauty to the Diaspora in the Early 1960s,” In Liberated Threads: Black Women, Style, and the Global Politics of Soul, 41–66, University of North Carolina Press, 2015, http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5149/9781469625164_ford.6. See images and additional reference to the African Nationalist Pioneer Movement, Grandassa models, and protest against Wigs Parisian in Kwame Brathwaite and Tanisha C. Ford, Kwame Brathwaite: Black Is Beautiful (New York: Aperture, 2019), 41-76.

- John M Goering, “Changing Perceptions and Evaluations of Physical Characteristics among Blacks: 1950-1970,” Phylon (1960-) 33, no. 3 (1972): 231–41, https://doi.org/10.2307/273523.

- Ibid.

- Congress.gov. “H.R.2116 – 117th Congress (2022-2022): Creating a Respectful and Open World for Natural Hair Act of 2022,” last modified March 21, 2022, https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/2116/text.

- Annie International, “Hot & Hotter Ceramic Hot Take Comb & Pik,” Annie International, 2023, https://www.annieinc.com/pages/search-results-page?q=hot%20%26%20hotter%20ceramic%20hot%20rake%20%26.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.