Door Politics: Physical Manifestations of Disability and Gender Discrimination

Danielle Lucchese

Editor’s Note: This piece was conceived as a spoken-word piece in addition to a design intervention through stickers (Fig. 1–5). In order to present the piece in as many accessible formats as possible, we have published the piece as an audio podcast, a video, and a transcript followed by an epilogue, which includes the original sticker designs.

It’s time to discuss door politics. Who is allowed in. Who gets out. Who has access. Accessed denied. Open doors. Closed doors. Locked doors. Specified doors. Where’s the automatic doors?

These are door politics.

What would you do if you couldn’t get in or out of a door? If it confined you like a caged lion at a zoo? If the sonic booms of its slam ripped through you like a box cutter penetrates a package—like a force field that no matter how many times you try to go through, you bounce right back to where you started?

These are door politics.

In second grade I began puberty, common with my disability.

My teacher had the “privates” talk with my classmates.

I had to stand in the front of the classroom. She closed the door. My body a specimen to be dissected.

These are door politics.

In third grade my teacher closed the door, called my name and informed the class that I was stupid and should be held back. She said I wouldn’t make it out of high school, and if I did, college will never be an option. The door to higher education locked. I had the key, but my brain was too foggy and I couldn’t see it.

These are door politics.

In sixth grade, there was a day that my history teacher was absent. With no substitute teachers to cover, the principal stepped in.

“Why are you here?” He asked.

“I have no idea” I replied. I had finally found the key. The door out of special education was unlocked; I was free.

These are door politics.

When I was a first semester college student, my professor pulled me into her office and shut the door. We were discussing eugenics in class. She begged me to speak. Begged for a syllable.

The classroom door shuts. A classmate shares that he believed disabled people were a waste of life.

My hand shot up. Tearing through the silence. My words cutting into him like a machete. Ripping him apart until he stood silent. Class dismissed. I walked out, shutting the door behind me.

These are door politics.

The spring semester of my sophomore year, I enrolled in a class called “Growing Up Female.”

The professor asked us “When did you learn what it meant to be female?”

I penned a tale of being bullied into femininity by a disabled girl. Make up covered my face like mask, concealing every lie I ever told myself: Fat. Ugly. Stupid. Locking myself in my room convinced I wasn’t deserving of friends. Of existence. Like how society constructs their doors: who gets in, who leaves. Like a sorting toy that calls for round blocks but all you have is square. Your identity doesn’t fit society’s expectations. Like a key that doesn’t fit the lock. So why impose limitations?

These are door politics.

As an English minor, I studied fairytales and fantasy. So many magical doorways. Magical access. But not unless you changed who you are. Alice had to change her size. Coraline opened a door to a brick wall. Harry Potter had to dream up his own room of requirement. Door, whose literal talent is to open any door doesn’t seem to have complete access. I thought literary doorways didn’t discriminate yet even they seem to dictate who has access.

These are door politics.

My disabled friends and I were often told that higher education was our door to freedom, to opportunity. Yet all we seem to do is encounter locked doors. Doors only accessible via tunnel. Tunnels that look like they’re from an episode of SVU. Doors that need to be automatic so we make it to class, yet we had to fight with the dean of the school for a year before two automatic door buttons were installed. Doors that display large, yellow silhouettes of a woman, man, and wheelchair user. Disabled and gender non-conforming go together when your bladder needs relief. When you don’t identity as man or woman. When you can’t make it passed the step leading into a conforming bathroom to everyone’s disbelief.

These are door politics.

In the fall of 2017, three months into my New School journey, I fell and broke my knee. Each door at the New School a struggle to open. I had to wait for someone to open every door to allow me to hobble through on crutches. Why are there no automatic doors? Guess I didn’t need to be concerned with those when I had a variety of male professors and students willing to assist the disabled damsel in distress.

These are door politics.

Last spring, my professor viewed disabled as a bad word. “differently abled” she’d insist. Shutting the door, literally and figuratively on my identity. But she asked me my preferred pronouns. She wanted to be inclusive of my gender. They/their. My preferred pronouns are they/their and for the millionth time the term is disabled NOT “differently abled.” Like a door whose hinges are loose, still usable. Until the door breaks free from its hinges. She didn’t think she was exclusionary until course evaluations. Door slammed on exclusion.

These are door politics.

It’s time to discuss door politics. Who is allowed in. Who gets out. Who has access. Accessed denied. Open doors. Closed doors. Locked doors. Specified doors. Where are the automatic doors?

These are door politics.

Epilogue

The ways in which we construct our environments are critical to our daily lives. Design presents humans with barriers and access points. John Heskett writes, “Design is one of the basic characteristics of what it means to be human, and an essential determinant of the quality of human life. It affects everyone in every detail of every aspect of what they do throughout each day.”1 Thus, how we design our environments determines who has access, the amount of access available and whom physical spaces embrace and deny. Doors present an opportunity to examine design controversy. This physical manifestation, created for boundaries and privacy—intentionally or not— demonstrates who has power and exemplifies an issue on contemporary design. For instance, doors limit both disabled individuals and people of various gender identities from utilizing these spaces.

Ultimately, door politics demonstrates visual, material and spatial politics associated with design. Material politics or how politics is exemplified through the presence or absence of objects, is demonstrated via stickers (Fig. 1–5) in order to construct political spaces and conversations surrounding disability and gender politics. Spatial politics are addressed because it draws on spaces in higher education, particularly those defined by doors like classrooms and restrooms, to discuss constraints and discrimination experienced by people with various gender and disability experiences. Both spatial and material politics exemplify the relationship between politics and physical spaces. Lastly, my project also encompasses visual politics because both the presentation of the project via stickers and spoken word performance and the physical spaces discussed create a visual representation of the discrimination faced by both groups.

This project aims to serve as a conversation starter on the ways doors in higher education represent both access and barriers from the perspective of disability and gender experiences. This project focuses on accessibility in higher education because having a college education, particularly in American society, grants you access to more career opportunities. The sticker designs you see here are intentional. Some stickers were placed on doors at the New School with the hopes of generating these much-needed conversations. The initial sticker designs were shared with both disabled individuals and people with various gender identities in order to gage reactions. Some of the stickers were removed off of school doors.

As a disability studies scholar, graduate student in sociology and a design studies minor, I view spatial design as the ideal way for my academic interests to intersect. As both a disabled and gender non-conforming person, I have experienced the implications of design in higher education that have both restricted my participation and conflicted with my identity. Doors, in a physical and symbolic sense, serve as a metaphor that embodies the ways in which physical spaces construct and perpetuate both ableism and gender discrimination. According to Heskett, “very few aspects of the material environment are incapable of improvement in some significant way by greater attention being paid to their design.”2 In other words, if we focused more on who we are designing spaces for instead of aspects such as superficial appearance or societal notions of gender, spaces, particularly those in higher education, would be more inclusive of and accessible to all disability and gender identities.

Stickers

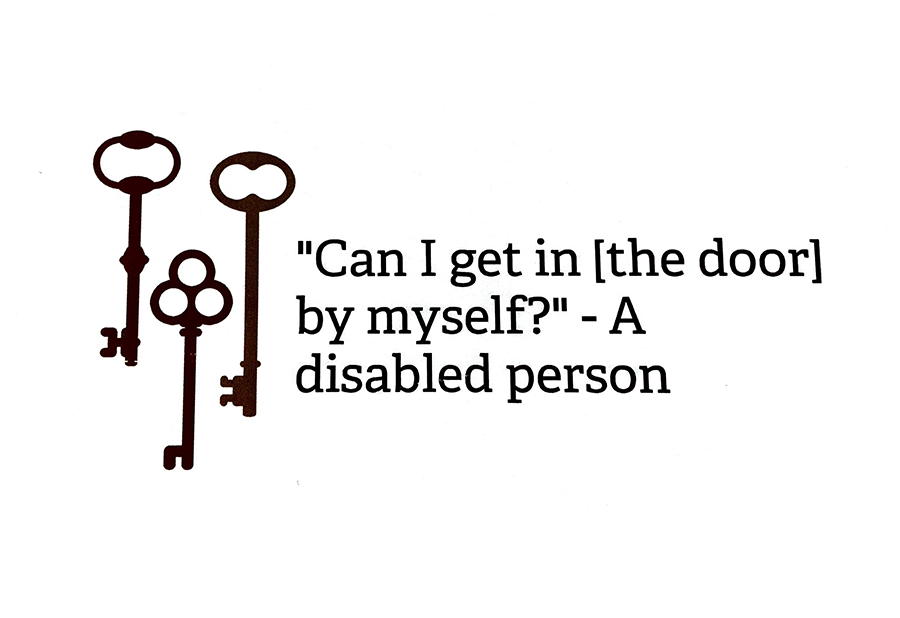

These stickers were designed as conversation starters when put on doors. The designs were inspired by signs created in eugenics & segregation periods in the United States. The “Keys” sticker (Fig. 1) includes a quote taken from an interview with a friend who uses a wheelchair and needs someone with her to open doors. Although automatic doors are often seen as a solution for people in wheelchairs, these doors might not always be within her reach.

Figure 1. Keys sticker. Design by Danielle Lucchese, 2019. Courtesy of Danielle Lucchese.

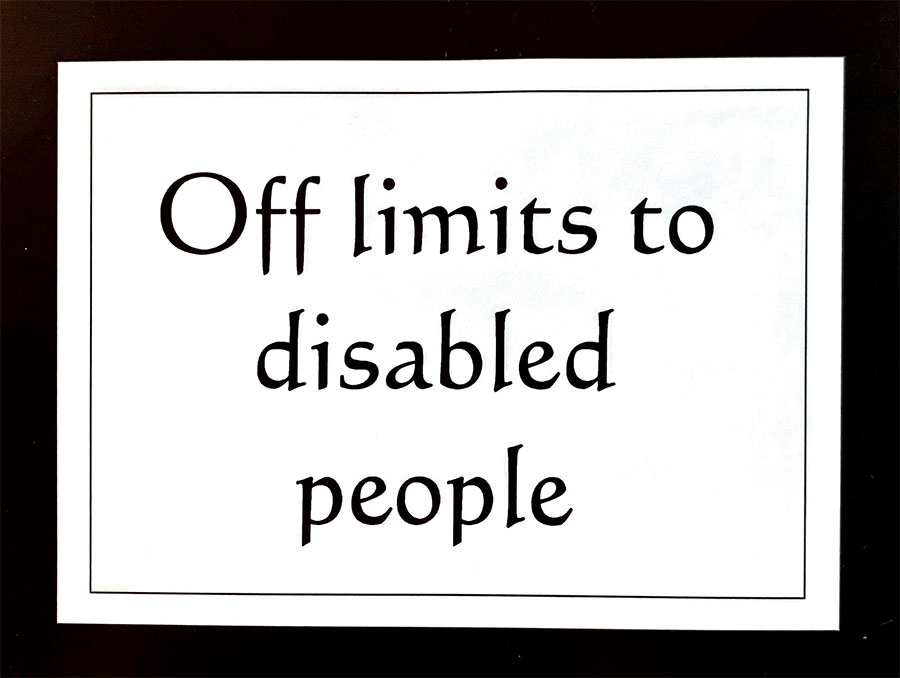

When I showed people the “Off limits to disabled people” sticker (Fig. 2), many of them described its design as “realistic.” This showed me that people are aware of ableism but weren’t prompted to link it to structures such as doors, and these stickers might help raise awareness.

Figure 2. Black and white “Off limits to disabled people” sticker. Design by Danielle Lucchese, 2019. Courtesy of Danielle Lucchese.

Although signs reading “No canes, walkers, wheelchairs or cripples” (Fig. 3) are not placed in buildings today, many buildings are not compliant with the Americans with Disabilities Act Standards for Accessible Design. If a disabled person can’t access or open the door independently, public places don’t allow us entry.

Figure 3. “No canes, walkers, wheelchairs or cripples” sticker. Design by Danielle Lucchese, 2019. Courtesy of Danielle Lucchese.

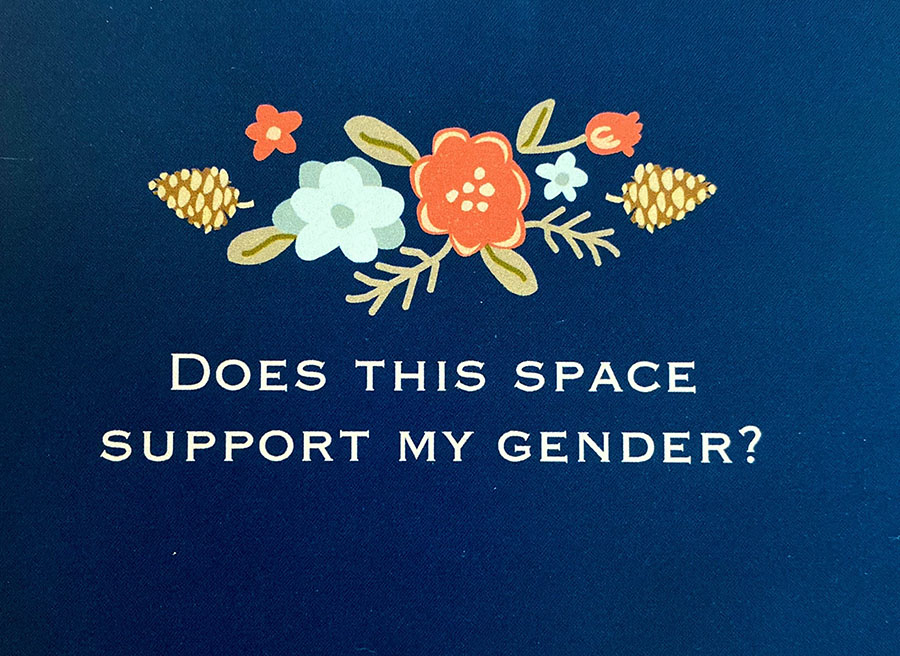

The question asked by Fig. 4, “Does this space support my gender?” is asked by many gender nonconforming, genderqueer, gender nonbinary and trans people. Once we disclose pronouns, transition, or demonstrate physical aspects of not conforming to the gender binary, our safety might be at risk. This is an urgent question that needs to be discussed.

Figure 4. “Does this space support my gender?” sticker. Design by Danielle Lucchese, 2019. Courtesy of Danielle Lucchese.

The final sticker in this project (Fig. 5) claims “This belongs to gender conforming people.” This sticker is meant to represent the arguments over gendered spaces such as bathrooms.

Figure 5. “This belongs to gender conforming people” sticker. Design by Danielle Lucchese, 2019. Courtesy of Danielle Lucchese.

Acknowledgements

This project would not have been possible without the advice of and conversations with some of my professors, colleagues and friends. I would like to thank Professor Jilly Traganou, who convinced me to submit this piece for consideration, Professor Vicky Hattam for suggesting the exploration of the concept of door politics, and Professor Caroline Dionne who willingly answered all of my questions and ultimately helped me decide to pursue a design studies minor. To my colleagues: Mariette Bates, Matthew Conlin, David Gordon, Jean Halley, Devva Kasnitz, Cara Liebowitz, Laura Martocci, Julie Maybee and Justine Pawlukewicz, for your insight and our conversations surrounding disability, gender and access, which helped inspire this project. Thank you to my friends, Melissa Maltez and Jennifer Weile for your feedback on the numerous stages of the project. Finally, I would like to thank the interviewees who shared their disability and gender experiences that inspired this spoken word piece.

Endnotes

1. John Heskett, Design: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 2.↵

2. Ibid.↵

Author Affiliations

Danielle Lucchese is a graduate student in The New School for Social Research’s MA Sociology program.

DESIGN STUDIES BLOG

DESIGN STUDIES BLOG