I Heart [Emoji]: Understanding the Effects of a New Language of Self-expression

Diana Duque

In Plato’s dialogue The Phaedrus, the protagonist, Socrates, shares with his interlocutor Phaedrus a disdain for the use of letters—predicting begrudgingly that the discovery of the alphabet “will create forgetfulness in the learners’ souls because they will not use their memories; they will trust to the external written characters and not remember of themselves.”1

Could it be that the discovery of, and pervasive use of emoji will also create forgetfulness in the learners of our time? Or could it be that we are at risk of forgetting our native, written tongue altogether, as Karl Marx suggests is the case with newly acquired language?

In like manner, a beginner who has learnt a new language always translates it back into his mother tongue, but he has assimilated the spirit of the new language and can freely express himself in it only when he finds his way in it without recalling the old and forgets his native tongue in the use of the new.2

It is unlikely that we will abandon modern linguistic and structural forms of written language altogether, but current trends in communication technology, including the ubiquity of smartphones, have drastically altered our traditional forms of writing and cultivated a novel and ephemeral form of graphic dialect: emoji. As the language of computers and the interface of smartphone technology has developed, expressive-yet-rudimentary emoticons—a series of printable characters such as :-)—have lost their appeal as they have been superseded by their digital cousin, the emoji.3 As exemplars of the new normal in digital communication, emoji represent a class of covetable widgets we took for granted until realizing modern-day text-based communication lacked something without it. Today, some might even say they can’t live without emoji.

The word emoji (both singular and plural) derives its name from the phonetic pronunciation of the Japanese word for pictograph: e (絵, picture) and moji (文字, character).4 This modality of writing employs what the anthropologist Nicholas Gessler describes as skeuomorphs, which function as a tool for disambiguation of our social transactions in everyday electronic communication. Essentially a short-hand of ideograms, Gessler defines these forms as “material metaphors instantiated through our technologies in artifacts.”5 Otherwise understood as images that resemble the objects or concepts they represent, emoji add meaning to an otherwise impersonal and expressionless digital language.

This form of graphic language has precipitated a global fluency among the estimated 2 billion consumers worldwide who own a smartphone and have the fluency to “speak” emoji.6 According to a 2015 report by the “emotional marketing platform” Emogi, a company that uses predictive algorithms to suggest relevant emoji, stickers, and GIFs in text messages, 92% of on-line consumers use emoji.7 Perceived as a novelty and a commodity, the library of emoji symbols continues to grow exponentially. Requiring periodical upgrades just like operating systems, emoji offer a social incentive for people to keep up with the latest medley of icons. The desire to remain relevant with the newest tools of inflection stems from consumers’ demand for more choice and better representation from these nuggets of self-expression. Brand images and consumerism help proliferate the use of symbols to represent feelings, ideas, and emotions. As the emoji keyboard becomes easier to use, the contagiousness of its pictorial language is irresistible. All it takes is to receive one in a text message to be made aware of its presence and to incite a similar response. We might even consider the genesis of the language of emoji to have come from a counterculture of technical expression. Emoji have gradually become more mainstream among smartphone owners and continuously lure consumers to the platform.

Evolving or Cheating: A Brief History of Shorthand’s Irresistibility

Considering the evolution of other complex modalities used to display and codify language, early writing systems can help provide insight into current forms of deconstructed text. The meta-linguistic knowledge inherent in writing systems can be recognized through visual cues found commonly in sign systems such as pictographs, pictograms, and hieroglyphics. Mnemonic devices such as these convey valuable information relating to cultural behavior in their inference of meaning and capacity to facilitate translation.8 Phoneticization and writing, according to the Rebus Principle, are important steps in the history of writing. Emojis can be used as a form of word play, or picture riddle of a pictogram, that gives way to a combination of word signs (for vowels and syllables) and phonograms (symbols that represent sound), increasing the power of logographic systems and allowing for greater expression of ideas.9 (Fig. 1)

Figure 1. A rebus for the movie title “Star Wars”: STAR + W + OARS. Movie Title Rebus by Open Clip Art Library User “mazeo,” 2010. Source: https://openclipart.org/detail/60325/movie-title-rebus.

In addition to the various modes of representation, it is also important to consider the ways in which written language is deconstructed for greater efficiency. Constructed language or longhand, found its abbreviated alternative in shorthand. In early shorthand systems dating back to Ancient Rome and Imperial China, scribes and clerics developed symbol systems that reduced letters to single strokes representing words. These techniques influenced modern shorthand systems such as stenography (narrow writing), brachygraphy (short writing), and tachygraphy (swift writing).10 Today’s system incorporates symbols or abbreviations for words and common phrases, allowing someone well-versed in the language to write as quickly as people speak.

Another non-standard writing style worth noting is telegraphese, or the telegraphic style, which is essentially a re-codification of language. Telegraphic style condenses writing by omitting articles, pronouns, conjunctions, and transitions. It forces readers to mentally supply the missing words.11 Designed as a clipped manner of writing that originated in the age of telegraphic prominence, telegraphese was used to abbreviate words and pack a lot of information into the smallest possible number of words or characters. Telegraph companies charged for their service by the number of words contained in a message, designating a maximum of 15 characters per word for a plain-language telegram, or ten per word for one written in code. This style of shorthand developed to minimize costs and convey the message clearly, eventually shifting from a business medium to a social medium.12

The word telegraphy derives from the Greek tele (at a distance) and graphein (to write). At the time of its inception, the telegraph allowed for the unprecedented long-distance transmission of textual or symbolic messages without an exchange of physical objects carrying the message. This type of exchange required knowledge and understanding of the method for encoding the message from both the sender and the receiver, which eventually led to the advent of today’s instant messaging and the visual code of those who use emoji. In many ways, telegram style was the precursor to modern language abbreviations employed in the Short Message Standard (SMS, or the standard text message). In the case of telegrams, space came at a premium cost and abbreviations were used out of necessity. This formula was revived for compressing information into the 140-character limit of a costly SMS prior to the advent of multimedia-messaging capabilities.

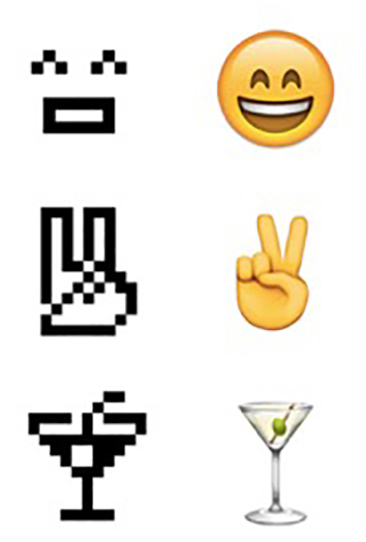

The emoji story began in 1991, with the Japanese national carrier Nippon Telegraph and Telephone (NTT) leading the way in the field of mobile communications. Early mobile devices, however, were rudimentary and visually clumsy, capable of receiving only simple information and communicating through basic text messaging. Shigetaka Kurita, an economist with no design or programming experience, was charged with developing a more compelling interface for NTT’s revolutionary “i-mode” mobile internet software. As a member of the “i-mode” team, Kurita proposed a better way to incorporate images in the limited visual space available on cell phone screens.13 (Fig. 2)

Figure 2. Left: Image of three original NTT emoji designed by Shigetaka Kurita, 1999. Right: Updated versions of the emoji library in Apple iOS 10, designed by Apple, 2010. Source: https://stories.moma.org/the-original-emoji-set-has-been-added-to-the-museum-of-modern-arts-collection-c6060e141f61.

Finding inspiration in manpu, a Japanese term for symbols used to express emotions in manga, as well as the pictograms found in instruction manuals and on informational signs, Kurita released the first set of 176 emoji in 1999.14 His first collection focused on three categories of emoji—media, services, and emotions. During a 2017 interview at the Museum of Modern Art [following the museum’s announcement to include Kurita’s original pixelated emoji in the permanent collection), the unlikely artist confessed that his favorite emoji were the smiling face and the heart. He said: “If you add a heart at the end of a sentence, any negative words feel positive.”15

Because of their ability to add context and emotion to texts, the emoji, or picture characters, became an instant success and were copied by rival companies in Japan.16 Emoji remained an exclusive feature to Japanese mobile phones until Unicode was forced to adopt the emoji keyboard to maintain global compatibility with Japanese texters in preparation for the debut of the Apple iPhone in Japan along with the release of the newest iOS, version 5.0.17

This new paradigm shift of self-expression has been embraced as a nuanced form of expression that extends beyond language barriers with the ability to communicate expediently. The language-neutral quality and optimal efficiency of the non-standard writing style lends itself to social media use. Vague, frivolous, and cute, emoji are well suited as punctuation for the type of shorthand-speak that no longer separates young from old. It is possible, however, that in the debate between technocrats and the technophobes, the ubiquitous use of emoji might be thought to have introduced a “dumbing down” of communication. As a modality of expression, this new paradigm shift, while seen by some as a convenient shortcut, might be viewed by others as a form of cheating.

Emoji are changing the way we communicate faster than linguists can keep up with or lexicographers can regulate. “It’s the wild west of the emoji era,” according to linguist Ben Zimmer. “People are making up the rules as they go. It’s completely organic.”18 Cautioning us of the inevitable mediation of language through technology, he anticipates a not-too-distant future in which, “the ever-expanding power and flexibility of our personal gadgets, combined with the computing prowess of servers we connect to “the cloud,” makes it a dead certainty that tech will rule the language of even the most reluctant neo-Luddite.19

Zimmer also believes emoticons can help us regain a lost sensitivity. “I don’t see it as a threat to written language, but as an enrichment. The punctuation that we use to express emotion is rather limited. We’ve got the question mark and the exclamation point, which don’t get you very far if you want to express things like sarcasm or irony in written form.”20 He also concedes that there are important limits on what emoji can communicate.

Emoji make it easier to convey different moods without much effort, however, they have limitations of their own in that they are inevitably tied to context. When asked to comment on a 2010 publication that included a full translation of Moby Dick into emoji, Zimmer called it “a fascinating project,” but noted: “If you look at those strings of emoji, they can’t stand on their own. They don’t convey the same message as the text on which they’re based.” (Fig. 3) After all, the emoji translation doesn’t quite have the same ring as “Call me Ishmael.”21

Figure 3. Excerpt from Emoji Dick or [Whale Emoji]. Fred Benenson, 2010. The first ever emoji book acquired by the Library of Congress. Source: www.emojidick.com.

Emoji as an Empathetic Asset in Communication

As technology mediates our relationships with one another, it continues to disrupt human closeness and connection. So how does the adoption of a universal system such as emoji confuse our ideas of culture, gender, and race? Technology, from Morse code to the mobile phone has allowed us to move further away from our physical selves. As we move into using abstracted modes of communication such as texts, tweets, and emoji, we should contemplate the impact that this form of communication has on our ability to connect with each other. Sociologist Luke Stark and academic researcher Kate Crawford expand on this notion by stating that, “As a genial and widespread vernacular from, emoji now serve to smooth out the rough edges of digital life.”22

Images have great communication value and are structured differently than text. They evoke right brain responses and turn on different thinking centers. As emoji operate in the realm of semiotics—understood as the cultural or emotional association that a symbol or image carries—the emoji’s connotation is understood as what it implies about the thing it represents. Acting more like punctuation, they provide cues about how to understand the words that came before them, like an exclamation point.23

Meanings are open to interpretation by the recipient. On this, Roland Barthes’ observation seems relevant to our current state of affairs. He affirms:

Finally, and in more general terms, it appears increasingly more difficult to conceive a system of images and objects whose signifieds can exist independently of language: to perceive what a substance signifies is inevitably to fall back on the individuation of a language: there is no meaning which is not designated, and the world of signifieds is none other than that of language.24

It is this visual understanding and sophistication which allows for a blurring between the signified (the idea of the object or idea being represented) and the signifier (the word, sound, or image representing it). in their capacity as skeuomorphic forms, emoji close the communication gap and move past words with a new formulation of written language.

Playing on emoji’s contextual limitations, the California-based designer and artist Rebecca Lynch created introji, or emoji for introverts. Lynch explained why she created a communication system that includes 40 introji:

I’m an introvert, too, but I realized my enthusiasm for being in a relationship sometimes overshadows my ability to read others’ signals. In my relationships and friendships, I use text messages with emoji, but often find myself reaching for a symbol that isn’t there, a little picture that could communicate a need or feeling easily where words might be misunderstood. So, I started making introji, emoji for introverts, as an easier visual way to tell a loved one or friend that you need more time and space.25

No system is perfect. The lack of representation and diversity in emoji has been widely discussed. In 2014, the Unicode Consortium published a study outlining a proposed plan for expanding the emoji library to include more diverse options.26 A non-profit organization whose membership is made up mostly from large software and technology companies such as Facebook, Microsoft, and Netflix, the Unicode Consortium decides what emoji should be included and what they should represent.

Almost 20 years after the introduction of Kurita’s 176 emoji, the release of Unicode 10.0 contributed 8,518 characters to “add support to lesser used languages.”27 By June 2017 the number of characters was set at a grand total of 136,690 in addition to the overall catalog of 2,666 emoji that followed the release of Version 5.0 of Unicode Emoji.28 This number included modified variations of emoji and Zero Width Joiner (ZWJ), also known as Unicode characters that join two or more characters together in sequence to create a new emoji, displaying sequences for gender, skin tone, and flags. Unicode has continued to make strides to adapt and be as inclusive as possible, but there will always be room for improvement. The following are examples of summary statements pertaining to diversity and gender included in Technical Report #51 by Unicode Emoji from November 22, 2016:

Diversity:

People all over the world want to have emoji that reflect more human diversity, especially for skin tone. The Unicode emoji characters for people and body parts are meant to be generic, yet following the precedents set by the original Japanese carrier images, they are often shown with a light skin tone.Most vendors are expected to support 69 unique images, with 24 of these supporting five additional skin tone variants.

Gender:

All other emoji representing people should be depicted in a gender-neutral way, unless gender appearance is explicitly specified using some other mechanism such as an emoji ZWJ sequence with a FEMALE SIGN or MALE SIGN. 10 of the new emoji have a base (non-gendered) emoji which may or may not display with a gender-inclusive appearance.29

On March of 2018, Apple presented Unicode with a proposal for the development and approval of new accessibility emoji:

Apple is requesting the addition of emoji to better represent individuals with disabilities. Currently, emoji provide a wide range of options, but may not represent the experiences of those with disabilities. Diversifying the options available helps fill a significant gap and provides a more inclusive experience for all. 30

Emoji tap into users’ personalized love for these simple cartoons. They can hold their own when tasked with the incomplete language that is tapped out in real time with clumsy fingers on tiny screens. The proliferation of smartphone technology, once again, shifts our language of communication and revisits the power of symbols to communicate. The challenge ahead will be how to maintain the communication rituals and behaviors of human and societal exchange that will save us from what Socrates fearfully foretold as a state of “knowing nothing” while appearing “omniscient.” The language of emoji is destined to endure, at least for a while. But if history is any indication, the lifespan of the emoji will depend on when the next state-of-the-art gizmo takes over.

1 Plato, Euthyphro. Apology. Crito. Phaedo. Phaedrus, trans. Harold North Fowler (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1914), 563, https://doi.org/10.4159/DLCL.plato_philosopher-phaedrus.1914.↵

2 Karl Marx, “The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte,” in Karl Marx and Frederick Engels – Selected Works. Volume 1 (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1966), 398.↵

3 Umashanthi Pavalanathan and Jacob Eisenstein, “More Emojis, Less :) The Competition for Paralinguistic Function in Microblog Writing,” First Monday 21, no. 11 (November 2016), http://firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/6879/5647.↵

4 Adam Murphy, “A Brief History of The Emoji,” Headstuff, August 3, 2017, https://www.headstuff.org/science/brief-history-of-the-emoji/.↵

5 Nicholas Gessler, “Skeuomorphs and Cultural Algorithms,” in Evolutionary Programing VII, ed. V. W. Porto, N. Saravanan, D. Waagen, and A.E. Eiben (Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer, 1998), 229.↵

6 “Number of Smartphone Users Worldwide from 2014 to 2020 (in Billions),” Statista, https://www.statista.com/statistics/330695/number-of-smartphone-users-worldwide/.↵

7 Brandy Shaul, “Report: 92% of Online Consumers Use Emoji (Infographic), Adweek, September 30, 2015. http://www.adweek.com/digital/report-92-of-online-consumers-use-emoji-infographic/.↵

8 Florian Coulmas, The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Writing Systems (Oxford, UK; Cambridge, Mass., USA: Blackwell Publishers, 1996), 406.↵

9 Florian Coulmas, The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Writing Systems, 556..↵

10 Ibid., 464.↵

11 Gerald J. Alred, Charles T. Brusaw, and Walter E. Oliu, Handbook of Technical Writing, 7th ed, (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2003), 522.↵

12 David Hochfelder, The Telegraph in America, 1832-1920, (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), 80.↵

13 Paul Galloway, “The Original Emoji Set Has Been Added to The Museum of Modern Art’s Collection,” MoMA: Features and Perspectives on Art and Culture (blog), Medium, October 26, 2016, https://stories.moma.org/the-original-emoji-set-has-been-added-to-the-museum-of-modern-arts-collection-c6060e141f61.↵

14Paul Galloway, “The Original Emoji Set Has Been Added to The Museum of Modern Art’sCollection.”↵

15 Rachel Mealy, “Emoji Inventor Shigetaka Kurita Says MoMA New York Acquisition ‘Feels like a Dream,’” ABC News, February 10, 2017, http://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-02-11/meet-the-man-who-invented-emoji/8249456.↵

16 Galloway, “Original Emoji Set.”↵

17 Ibid.↵

18 Ben Zimmer, “The Future Tense,” New York Times, February 25, 2011, https://www.nytimes.com/2011/02/27/magazine/27fob-onlanguage-t.html.↵

19Ben Zimmer, “The Future Tense.”↵

20 Ibid. ↵

21 Alice Robb, “How Using Emoji Makes Us Less Emotional,” New Republic, July 7, 2014, https://newrepublic.com/article/118562/emoticons-effect-way-we-communicate-linguists-study-effects.↵

22 Luke Stark and Kate Crawford, “The Conservatism of Emoji: Work, Affect, and Communication,” Social Media + Society (July – December 2015): 1.↵

23 “Emojis and the Language of the Internet,” Languagemagazine.com, April 6, 2015, https://www.languagemagazine.com/2015/04/emojis-and-the-language-of-the-internet/.↵

24 Roland Barthes, Annette Lavers, and Colin Smith, Elements of Semiology (New York: Hill and Wang, 1968), 10.↵

25 Rebecca Lynch, “Introducing Introji—Emoji for Introverts,” Guardian, February 17, 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2015/feb/17/introducing-introji-emoji-for-introverts.↵

26 “Unicode Technical Standards #51,” Unicode Emoji, Unicode, May 18, 2017, http://unicode.org/reports/tr51/.↵

27 “Unicode 10.0,” Unicode, June 20, 2017, http://unicode.org/versions/Unicode10.0.0/.↵

28 “Emoji Statistics,” Emojipedia.org, http://emojipedia.org/stats/.↵

29 “Unicode Technical Standards #51.”↵

31 Apple Inc.,“Proposal for New Accessibility Emoji,” Unicode, March 2018, https://www.unicode.org/L2/L2018/18080-accessibility-emoji.pdf.↵

Author Affiliations

Diana Duque

MA Design Studies, Parsons School of Design

DESIGN STUDIES BLOG

DESIGN STUDIES BLOG