A Design Response to a Multi-layered Complexity: People’s Palaces

Irem Yildiz

Absract

Beginning with the effort to decipher the dynamics of the passionate love-hate relationship between the Palace of Culture and Varsovians(natives or residents of Warsaw), this paper focuses on the ways to dismantle these dynamics by using design as agency from a case study: a design intervention proposal, People’s Palace. People’s Palace is created by Alana Weiss Nydorf, Irem Yildiz, Oleksandr Holiuk, and Zofia Borysiewicz for The Palace of Culture:An Exploration in Design, Humanities, and Social Sciences, an intensive course taught by Susan Yalevich and Mateusz Halawa at Parsons The New School for Design in collaboration with School of Form, Poznań, during the five day workshop in Warsaw in Spring Break 2017. While the first part of the paper focuses on the theoretical ways to understand complexities, problematics, and the multi-layered nature of the Palace of Culture; the second part focuses on the proposal itself by going back to the theory and explores how design would respond to such social, political, and cultural complexity.

The Dynamics and the Multi-Layered Nature of a Complexity

The Palace of Culture and Science, an embodiment of a long-lasting, love-hate relationship, has been standing glamorously in Warsaw since 1955, keeping its name as the tallest building in Poland (Fig. 1). This gift of Stalin to Varsovians after the Second World War was termed a Trojan horse by David Crowley.1

Figure 1. Main Entrance of The Palace of Culture and Science, Warsaw, 2017. Courtesy of Irem Yildiz.

The Trojan Horse comparison was originally based on the Palace’s main concept and function. The Palace of Culture and Science (PKiN – Pałac Kultury i Nauki) is part of the “House of Culture” concept in the Soviet Union, which are major public clubs comprised of various social and cultural activities. The Palace of Culture and Science stands as a great representative of its kind by being the tallest Palace of Culture outside of Russia and also the second tallest one in the world. As a true Soviet structure, the building was not only conceptualized and built by a team of Soviet architects, engineers, and laborers led by Soviet architect Lev Rudnev, but also many of the building’s materials were produced in the Soviet Union.

From top to bottom, the Palace of Culture was not only a gift from Stalin but also the embodiment of his power in the heart of the city.

As a hub of various social and cultural activities, PKiN has four theatres, two universities, a multiplex cinema, a dance academy, multiple restaurants, pubs, and cafes, and a three thousand seat Congress Hall that serves as the meeting room for the Warsaw City Assembly and various departments of the municipal administration. PKiN also serves as the headquarters of the Polish Academy of Sciences and as a Palace of Youth.2 Even though the Palace is surrounded by skyscrapers and shopping malls, its structure dominates the skyline of Warsaw as well as the social and cultural scene of the city.

To illustrate how the Palace holds a crucial part in daily life of Varsovians we can refer to the work of anthropologist Michal Murawski’s, who has a dissertation and a forthcoming book on the Palace of Culture and Science. According to a survey he conducted with five thousand participants:

77% of respondents agreed that the Palace ‘exerts an impact’ on the city (52% on architecture, 49% on urban planning, 43% on “urban culture” and 36% on “urban psychology”). Of those born in Warsaw, 77% have childhood memories associated with the Palace; 45% of current Warsaw-dwellers have a direct view of the Palace from their home or workplace, 61% visit the Palace at least several times a year, 22% cross its threshold more than once every month.3

The Palace’s myriad effects on people and the city illustrate how various memory types exist, intersect, and even overlap in an urban context. Aleida Assman, a cultural anthropologist who focuses on cultural and collective memory, states four modes of memory by contemplating the interaction between individual and collective memories. Her categorization of four levels or “formats of memory” are individual memory, social memory, political memory, and cultural memory.4

To explain individual memory, Assman emphasizes various memory systems of the human brain. Based on that, there is “procedural” memory that stores habitual body movements and skills such as swimming, “semantic” memory that stores the knowledge origins from conscious learning activities, and “episodic” memory that includes autobiographical experiences. The most distinguishing characteristic of episodic memories is that its one perspective leads to fragmentation and non-interchangeability. These individual and unique fragments connect to each other creating a network based on the interaction and communication of people, causing a continuous evolution of individual memories.

Social memory is the collection of recycled individual memory accumulated through various social interactions such as oral communication and story-telling. Social memory deciphers how people perceive and remember historically important events. While social memory originates from lived experience, political memory originates from collective identities and acts that have been constructed based on social memory. It is a trans-generational memory similar to cultural memory. Assman differentiates cultural memory from other modes of memory by pointing out its complex nature blended by forgetting and remembering.5 Cultural memory is stored by museums, libraries, and archives that keeps it accessible to a general public.

Murawski’s survey shows the Palace’s place in the memories of Varsovians has transferred through generations, with the 77 percent of the participants agreeing on the overall effect of the Palace on the city and 63 percent of them indicating the Palace as Warsaw’s “most important and easily identifiable symbol.”6 For many Varsovians, the Palace has been the focal point of various memories including swimming classes at the ages of five and six, museum visits, first dates at the movies, and finally, attending college classes or public lectures.

However, these memories do not make the Palace a symbol of romantic nostalgia. Because of its historical and political meaning, the Palace is seen as the symbol of Poland’s communist times reflecting Stalin’s once dominating power. Murawski uses a great description of the Palace from Tadeusz Konwicki’s 1979 novel A Minor Apocalypse to explain the symbolic meaning of the Palace:

once a ‘monument to arrogance, a statue to slavery, a stone layer cake of abomination’ transformed into merely ‘a large, upended barracks, corroded by fungus and mildew, and old toilet forgotten at some central European crossroad.7

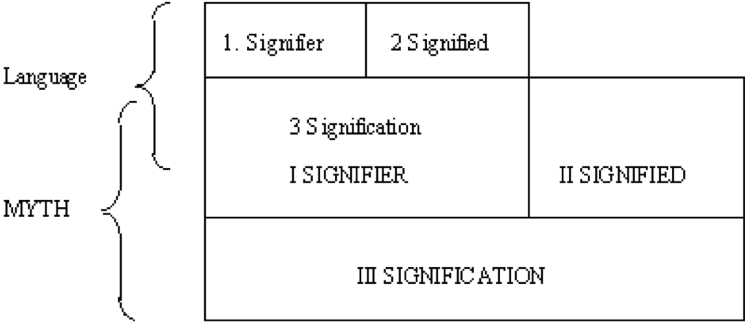

These hidden meanings beneath surfaces and complexity of symbolism bring Barthes’ semiological system diagram, stated in Mythologies, to mind (Fig. 2). Barthes suggests a dual semiological system to illustrate myth. To explain briefly, he claims that semiotics theorizes the relationship of two terms; signifier (linguistic representation/word) and signified (object).8 While the signifier is any kind of material being, the signified is the idea or meaning of that material being.

Figure 2. Dual semiological system diagram, Roland Barthes, Mythologies, 1957. Courtesy of Editions du Seuil.

In other words, the signifier represents form and the signified represents concept. Barthes’ point of view shows that the key of the system is the signifier. The signifier is crucial to create or recreate a myth, the beginning point, which would trigger the construction of the system. Based on the form of the material (signifier), the meaning (signified) is shaped. The Palace of Culture’s complex meaning is shaped by multiple events, politics, oral histories, and lived experiences. On one hand, it is an enormous creature that makes the most painful times of a nation unforgettable. On the other hand, it is a joyful place of remembrance for first loves and the witnessing world-renowned performances.

How Would Design Respond to Such Complexity?

Thinking about how design would respond to this multi-layered complexity, our main goal as a project team was to create a way to open lines for communication. Based on the theoretical deciphering of this love-hate relationship, the beginning point for the design process emerges as a play with the dynamics of signification of the Palace which then aims to reconstruct memories. It is important to specify here that the purpose is not to erase memory, but to create peace amongst all modes of memory as well as to create awareness to the existence of the complexity.

As stated earlier, a change in the signifier would affect the whole system. Therefore, new types of signification of the Palace can open ways for new meanings; or, new images can create an inclination towards one side of the story. The first challenge here was to decide what kind of an image set would create an inclination to reconciliation. By using these images or forms as a tool, memories would be open to reconstruction and then hopefully, the reconstructed memories would become the dominant recurring memories. The second challenge is then, what could be designed to allow new memories to arise?

Reconfiguration is key in the proposed design. The concepts of memory and myth are deconstructed with theoretical conversations and reconstructed using design as the agency.

People’s Palace (Ludzki PaŁac)

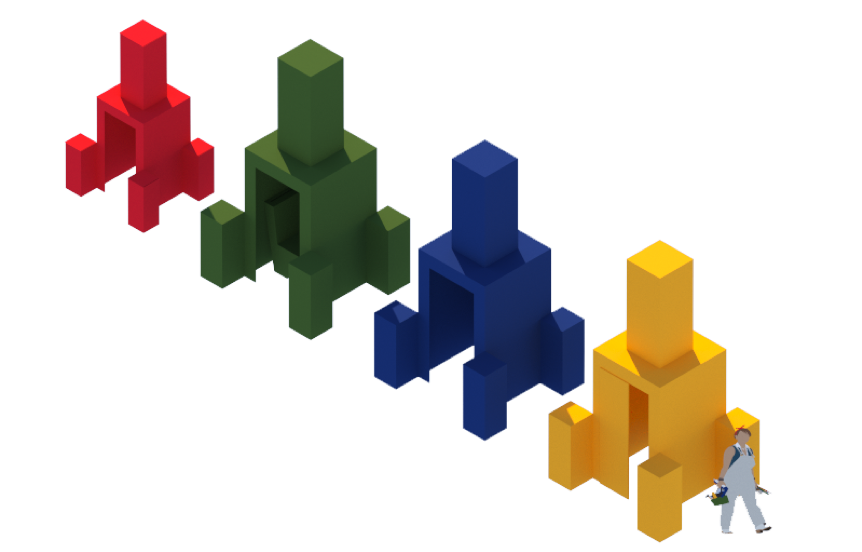

People’s Palace is a tactical design response that aims to modify the Palace of Culture and Science’s image as a frightful structure or a symbol of Soviet Union’s dominance over Warsaw. By shrinking the building’s scale to that of a single human being intimacy could develop between the Palace and people. (Fig. 3)

Figure 3. Main visual of People’s Palaces. Courtesy of Irem Yildiz.

Despite plenty of propositions to destroy it, the Palace has managed to survive and hold a place in Varsovian’s memories by serving as a witness to innumerable first romances, childhood delights, civic debates, performances, and— in short— the lives of Varsovians. People’s Palace is about provoking, collecting, and sharing these memories of the people and presenting varied occasions for new conversations.

To create a physically and emotionally intimate space, which would lead to open sharing, communication, and interaction; we took inspiration from the notion of the toy. Barthes defines toys as the tools that adults use to implement the ideas and principles of the adult world to children.9 Also, toys are the objects that people feel an affinity and protectiveness for. With these concepts, People’s Palace is designed on a scale so that people would associate it with a playhouse meant for only a single occupant at a time. As a part of this idea, the chosen colors of the Palaces reflect common colors found on many children’s toys: red, blue, yellow, and green. Going back to semiotics, design creates its own image to shape a certain meaning in people’s minds.

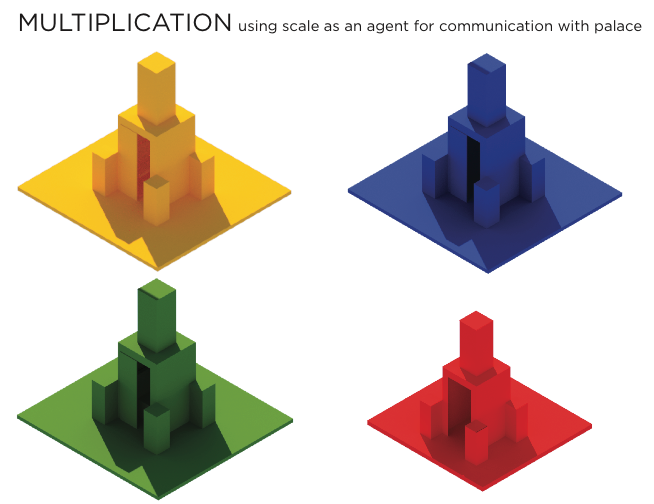

People’s Palace Project ended up consisting of four miniature Palaces of Culture fitted with various experiential interiors (Fig. 4). The idea of multiplication was inspired by Varsovian’s obsession with the Palace and the efforts to pluralize it. You can see various replicas and symbols of the Palace around the city and also in the Palace itself, ranging from Palace salt and pepper shakers and keychains to a little Palace replica built from glass Coca-Cola bottles (Fig. 5).

Figure 4. Second main visual of People’s Palaces. Courtesy of Irem Yildiz.

Figure 5. An installation of the Palace of Culture from Coca-Cola Bottles. Courtesy of Irem Yildiz.

Instead of seeing the Palace within the Palace itself, the People’s Palace Project invites you to experience it in the urban context. Each People’s Palace, with its own specific communicative function, is placed in a notable Varsovian location with the purpose of being a part of daily life. The stories, photos, and memories collected by the Palaces would be shown on the People’s Palace website as well as the People’s Palace official Instagram account, which would serve as a contemporary informal archive.

Going back to memory, People’s Palace is inspired by people’s feelings of affection towards the Palace overriding their memories of oppression associated with it. To create a communication between these Palaces and the Palace itself, in the spire of each palace sits one of a series of wireless routers— each blinking in harmony with one another, and in response to the flashes of the Palace.

Version.1. Palace as a Mailbox

The main inspiration for this version of Palace is the unique phenomenon of Varsovians sharing their feelings and thoughts about the Palace in written letters addressed to the Palace. When this is done, Varsovians sometimes address the Palace as person and speak to it as if it was capable of consciousness. Here is an example from Murawski’s book, an e-mail from a visitor to the events department of the Palace inquiring about a proposal:

First of all, let me explain to you why it is the Palace in particular, which interests me. Although we don’t live in Warsaw, every time we come here we have to see, touch and admire it for a moment … For us this is a magical place – in the midst of glass and nondescript skyscrapers there is He – the most extraordinary building (niesamowita budowla) I have ever seen in my life … That enormity … Its extraordinary facade, its interesting history, etc., all make this place unique.10

The Palace as a mailbox refers to these e-mails, messages, and the feelings that initiated them. It invites people to communicate with the Palace via one of the most analogue pathways and in one of the most poetic spots of Warsaw, near the river. Inside this Palace there is a chair with a mailbox attached to its back, a table with a pen, and a pile of postcards, resembling what one could find in any post office. Visitors write a message for the Palace on a postcard and put it into the mailbox. Then, if they would like to write down their address on the postcard, they will receive a lipstick-kissed postcard and greetings from the Palace of Culture and Science itself.

Version.2. Palace as a Telephone Booth

One of the most amazing characteristics of the Palace of Culture is its randomness and the value behind that. Since it is an enormous and complex structure with a very diversified program, it is almost impossible to manage everything according to a single rationale. This situation allows unique juxtapositions that one hardly notices in the rush of the daily life. However, someone walking into the Palace with fresh eyes might recognize these unexpected juxtapositions, such as coming across a large room filled with designed furniture at the end of a long and narrow corridor and then noticing contemporary brandings of a corporate event on one of the top floors of the tower.

This version of the People’s Palace is inspired by the Palace’s randomness, in particular, the old phones that you occasionally come across in the Palace (Fig. 6).

Figure 6. Lower level of the Palace of Culture and Science. Courtesy of Irem Yildiz.

A visitor steps inside of this People’s Palace and picks up a telephone receiver, which randomly triggers a connection to a phone within the actual Palace of Culture, initiating a conversation between a booth visitor and whoever picks up on the other end. Prompts on the wall of the People’s Palace propose some topics of discussion which visitors can use to start a conversation. All conversations would be recorded and put online, contributing to the Palace’s oral history archive.

Version.3. Palace as a Photo Booth

The purpose of the Palace as a photo booth is to make people see and remember joyful moments of the Palace by using both the concept of selfie as a tool and also critiquing the addiction of the concept of the selfie. With this purpose, it is located in the most touristic area of the city, Old Town Square. People take photos of themselves in the booth hoping to get their selfies. However, they end up with unexpected pictures of the Palace that come out of the machine. On the backside of the booth, there is a message telling the visitor that their selfies will appear on the project’s website if they wish or the visitors can e-mail the photos to themselves using the machine. This version of Palace tackles today’s ways and habits of communication and share their thoughts in a humorous way. It can break the ice between people and the Palace.

Version.4. Kid’s Palace

This version is slightly smaller than others and particularly designed for kids. The purpose is to create a positive impact of the Palace in children’s’ minds by allowing them to engage with it various playful ways. Kid’s Palace is an interactive storytelling machine, which tells the history of the Palace through songs and stories to children. The idea is to initiate communication between kids and the Palace by allowing them to engage and contribute to social memory by using contemporary tools.

Conclusion

People’s Palaces is a tactical design response to the results of a strategic design activity. In his essay “Just Re-Do It: Tactical Formlessness and Everyday Consumption,” Jamer Hunt illustrates how the dynamics between tactics and strategies create a dialectical process. He associates strategies with monumentality and permanence, and tactics with fluidity and adoptability.11 From this point of view, the Palace of Culture with its resistant monumentality stands as an example of a strategy. On the other hand, People’s Palaces with their purpose of dismantling the current dynamics and exploring alternative situations by using design as agency make the project a tactical design response.

Assman states that a vast amount of memory waits passively until triggered by an external incentive.12 The main purpose of People’s Palaces is to trigger those hidden memories of Varsovians by using design and various conventional and contemporary communication tools as its agencies. In addition, opening a way to new memories is the secondary mission of People’s Palaces. Not trying to create a whole new image, but trying to change the meaning (signified) by changing the image (signifier) would change the dynamics of this dissonant love-hate relationship. By collecting data and online archiving, People’s Palaces would be able to transform individual and social memories in collective memory. The experiences and memories would continue to be transmitted among generations.

Endnotes

1 David Crowley, “People’s Warsaw / Popular Warsaw,” Journal of Design History 10 (1997): 203-223.↵

2 Michal Murawski, The Palace Complex: The Social Life of a Stalinist Skyscraper in Capitalist Warsaw, (2016).↵

3 Murawski, The Palace Complex: The Social Life of a Stalinist Skyscraper in Capitalist Warsaw.↵

4 Aleida Assman, “Memory, Individual and Collective,” The Oxford Handbook of Contextual Political Analysis, ed. Robert E. Goodin and Charles Tilly (Oxford University Press, 2006).↵

5 Assman, “Memory, Individual and Collective.”↵

6 Murawski, The Palace Complex: The Social Life of a Stalinist Skyscraper in Capitalist Warsaw.↵

7 Murawski, ibid.↵

8Roland Barthes, Mythologies (New York: Hill and Wang, 1984).↵

9Barthes, Mythologies.↵

10Murawski, The Palace Complex: The Social Life of a Stalinist Skyscraper in Capitalist Warsaw.↵

11 Jamer Hunt, “Just Re-Do It: Tactical Formlesness and Everyday Consumption,” Strangely Familiar: Design and Everyday Life, curated by Andrew Blauvelt for the Walker Art Center, 2003.↵

12Assman, “Memory, Individual and Collective.”↵

Author Affiliations

Irem Yildiz

MA Design Studies, Parsons School of Design

DESIGN STUDIES BLOG

DESIGN STUDIES BLOG