Augmented Imagination: Machine Learning Art as Automatism

Philipp Schmitt

In the periphery of the landscape that is the current boom of machine learning (ML) sits a playground for tech-savvy creatives who are re-appropriating the technology for their own means.

In one corner, there are designers focusing on applying the strengths of neural networks to the design field. They dream up new, “intelligent,” generative tools that, for example, help analyze data or produce a thousand variations of a design in an effort to select the best one.1

In another part of this playground sit artists who are interested in the new medium’s own expressiveness: “[ML] is becoming a tool, just like painting,” artist Trevor Paglen told me at the opening of his recent exhibition.2 Paglen and other artists like Mario Klingemann and Sascha Pohflepp have recently produced interesting visual work—what we could call machine learning art (MLA)—that prompted the thoughts behind this essay.

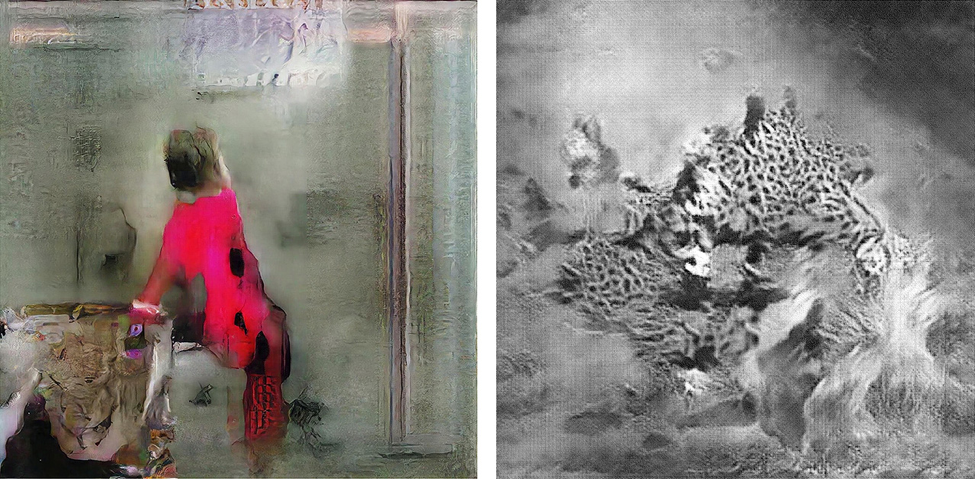

Figure 1. Left: Mario Klingemann, Untitled, Solitary Confinement Series, 2017.

Right: Sascha Pohflepp, Spacewalk: Carnivores 3, Generation 320, 2017.

Many images produced by artists using ML (such as Fig. 1) are similar in their visceral evocative qualities, their organic “brushstrokes” and textures, their surreal creatures and objects. They are usually made to depict familiar objects and draw from visual material of this world, but have something alien to them that is highly fascinating.

The technology that creates these works wasn’t invented for or by artists—scientists and engineers use these images as well (but tend to discard them after their work is done). Scientists use these images to better understand how their neural network works—or doesn’t. In other words, the images—as a debugging tool or artwork—often tell us more about the machine itself and the people who made it rather than about the depicted subject matter.3

MLA is interesting because of the network’s tendency to misrepresent or represent in alien ways. The glitches in the system are what makes the product fascinating. As researchers are working on making the technology more accurate and explicable, its associative potential decreases. Any sufficiently advanced MLA system loses its magic, so to speak.

Machine Learning Art and Surrealism

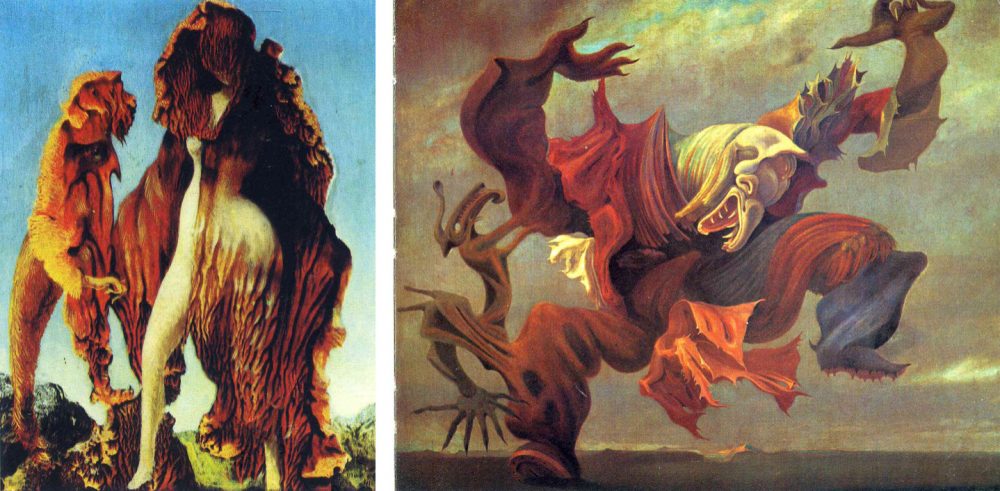

MLA works sometimes resemble the paintings and drawings of Surrealist artist Max Ernst. Surrealists like Ernst sought to resolve what they believed to be previously contradictory conditions of dream and reality. They borrowed techniques from psychoanalysis to stimulate their art, believing that “the creativity that came from deep within a person’s subconscious could be more powerful and authentic than any product of conscious thought.”4

Figure 2. Left: Max Ernst, Wizard Woman, 1941. Right: Max Ernst, The Angel of the Home or the Triumph of Surrealism, 1937.

This paper does not proclaim Paglen, Klingemann, or their computers as contemporary Surrealists. Rather, the goal is to compare MLA with Surrealist techniques to propose a different way of thinking about machine learning as a creative tool.

What do Surrealist Automatism and Machine Learning Art Have in Common?

MLA does not adhere to the Surrealist movement but to its techniques. The Surrealist artist’s toolbox features a whole range of “automatisms”—art-making techniques that poke the subconscious, so to speak. In physiology, the term automatism describes automatic bodily movements. For example, we don’t tend to consciously control our breathing, and that is what automatisms are supposed to achieve in making art.5 “Pure psychic automatism… the dictation of thought in the absence of all control exercised by reason and outside all moral or aesthetic concerns.”6

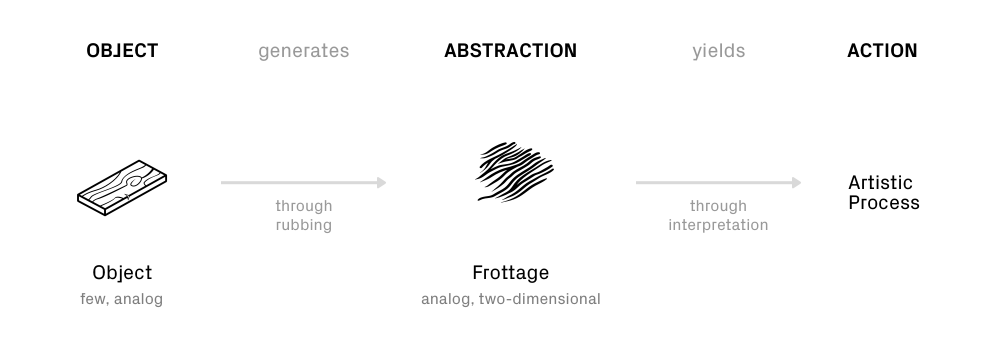

There are many techniques of automatism, a popular one being Frottage. Frottage is a technique popularized (not invented) by Max Ernst in 1925. This technique picks up textures from structured surfaces by placing a sheet of paper on top and rubbing over it with a pencil.7

Frottage starts with an object (Fig. 3). By transferring the object’s textures to a canvas or a piece of paper, the artist creates a two-dimensional abstraction of the object. Often, multiple frottages are combined on a single sheet. The textures form evocative images. They prompt connections to other, often unrelated objects, places, or creatures that the artists responds to by refining the image in an effort to bring out more of the desired subjects.

Figure 3. The Frottage process. Image courtesy of the author.

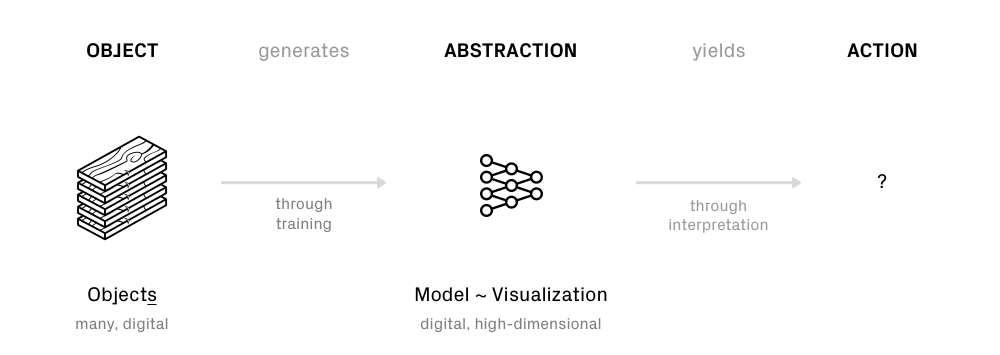

MLA often follows a similar process (Fig. 4). Leaving aside technical details, this process can be generalized as follows: It starts with a dataset of thousands or tens of thousands of objects (or digital representations thereof). Through training, the artificial neural network creates a high-dimensional abstraction of the object’s features: the model. A model can be made to visualize what it “sees.” It reveals textures and shapes somewhat characteristic to the object in ways that often look similar to frottage.

Figure 4. Simplified machine learning art process. Image courtesy of the author.

I would argue that both processes create images with similar evocative qualities. But there are also, of course, differences between the two. One is that neural networks inherently strive for representation whereas frottage and Surrealism in general seek to dissolve it: Although MLA generally avoids going there, neural networks are capable of learning to generate realistic-looking images from noise, ones and zeros, artifice. A lot of research in generative ML systems works towards this goal of realism. Surrealist automatism, on the other hand, suggests that things are never only one thing; that any surface bears fantastic creatures and other worlds, you only need to make them visible.

Machine Learning as a Tool for Imaginaries

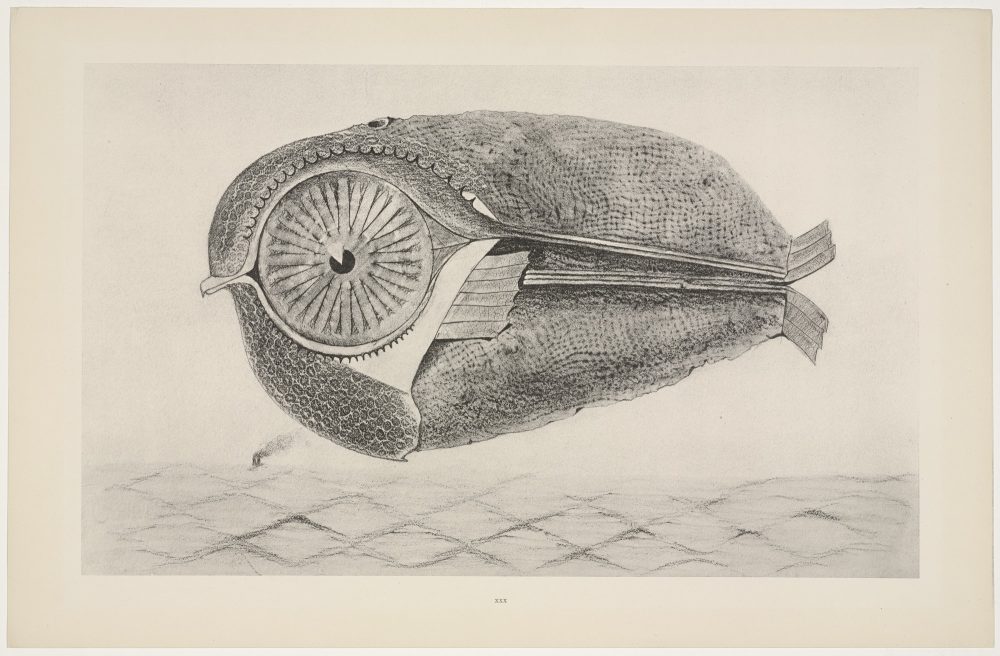

Frottage is generally used to launch an artistic process whereas MLA does not. Max Ernst published his experiments with frottage in a 1926 publication titled Histoire Naturelle (Fig. 5). The drawings in the series aren’t just rubbings that leave the interpretation to the viewer. We see fantastic landscapes and creatures, rendered with the precision of scientific illustration and inspired by what Ernst saw in a piece of wood.8 The frottage was the start of a process rather than the end of one.

Fig. 5: Max Ernst, The Fugitive (L’Évadé) from Natural History (Histoire Naturelle), c. 1925, published 1926 © 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris.

In current, early MLA the images mostly stand for themselves as artworks. The tool itself is the center of attention.9 In a way, the artists stop at the point where things get interesting.

What if we employed this means of making images neither as practical debugging nor as art in itself but rather as an art and design tool for mind bending—like Surrealist frottage; one that caters to the subconscious, the associative, the imaginary rather than the rational?

1 Patrick Hebron, “Rethinking Design Tools in the Age of Machine Learning,” Medium.com, April 26, 2017, https://medium.com/artists-and-machine-intelligence/rethinking-design-tools-in-the-age-of-machine-learning-369f3f07ab6c.↵

2 Trevor Paglen, “A Study of Invisible Images,” Metro Pictures, September 8, 2017, http://www.metropictures.com/exhibitions/trevor-paglen4/press-release.↵

3 Trevor Paglen, “Invisible Images (Your Pictures Are Looking at You),” The New Inquiry, October 02, 2017, https://thenewinquiry.com/invisible-images-your-pictures-are-looking-at-you/.↵

4 MoMA, “MoMA | Surrealism,” Museum of Modern Art, https://www.moma.org/learn/moma_learning/themes/surrealism.↵

5 Tate, “Automatism – Art Term,” Tate, http://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/a/automatism.↵

6 André Breton, “Manifesto of Surrealism,” Manifestoes of Surrealism, https://www.tcf.ua.edu/Classes/Jbutler/T340/SurManifesto/ManifestoOfSurrealism.htm ↵

7 Tate, “Frottage – Art Term,” Tate, http://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/f/frottage.↵

8 MoMA, “Natural History (Histoire naturelle) | MoMA,” The Museum of Modern Art, https://www.moma.org/collection/works/portfolios/10056?locale=en.↵

9 EyeEm, “Photography through the Eyes of a Machine,” EyeEm, September 08, 2017, https://www.eyeem.com/blog/mario-klingemann-ai-art/.↵

Author Affiliations

Philipp Schmitt

MFA Design and Technology, Parsons School of Design

DESIGN STUDIES BLOG

DESIGN STUDIES BLOG