Issue 5 2021 Short Essays

When the West Was Last: Chinese Imari Porcelain for the Mexican Market

Abby Sumner

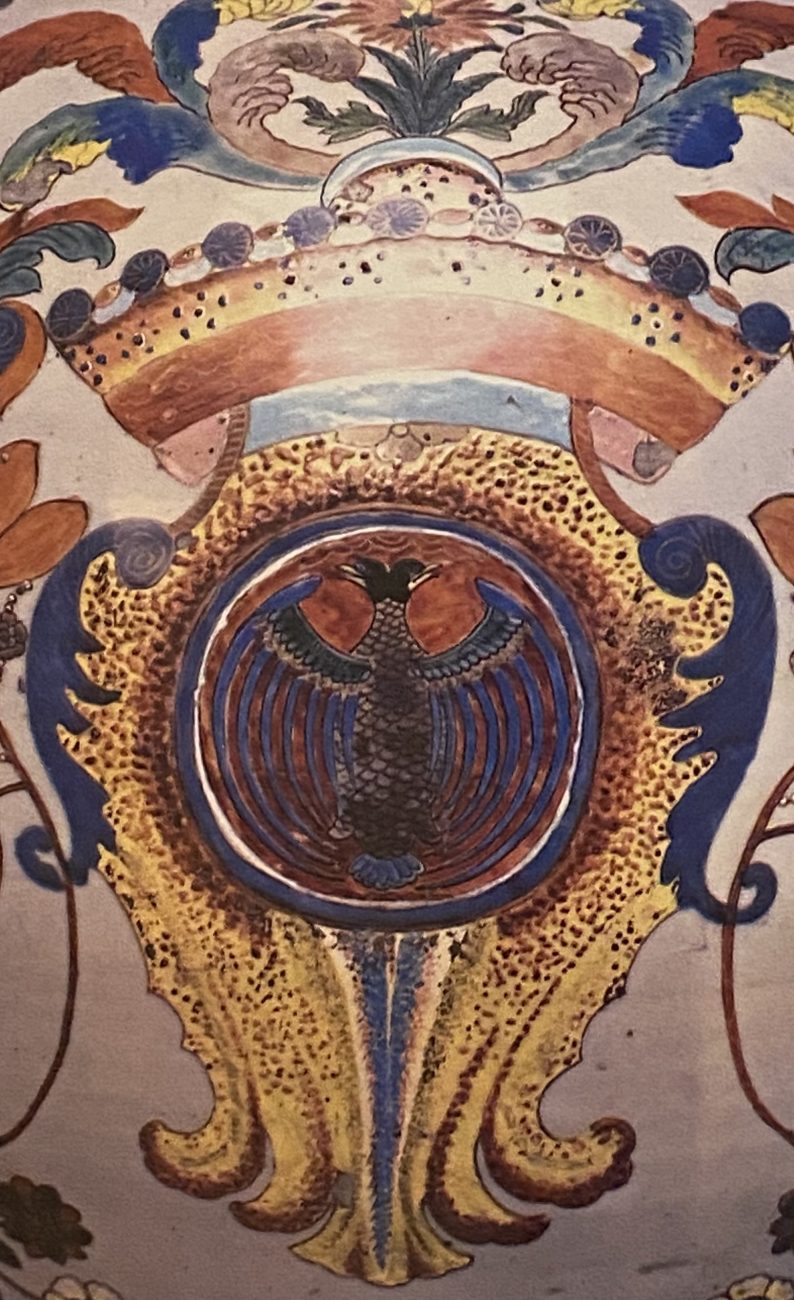

Fig. 1 Front view of the Chinese Imari shaving basin produced 1690–1700. Double-headed eagle motif represented in the center and at the top inverse. Chinese Imari Shaving Basin (for the Mexican Market). Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum, New York, 2020.

Chinese porcelain is one of the world’s most precious materials. It is well known for its utility and its delicate aesthetic but perhaps less known for its significance in trade and design on a global scale. Porcelain’s transcontinental reach demonstrates the continuity of material culture and its coexisting histories over several centuries. This is evident in the motifs used across various styles of Chinese porcelain design. A Chinese Imari shaving basin in the collection of Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum from the turn of the eighteenth century provides an excellent example of transcontinental exchange among Asia, the colonized Americas, and Europe. This object also suggests a local relationship between the potters of Jingdezhen, China and Puebla, Mexico through their shared knowledge and use of motifs in porcelain design.

For a seemingly utilitarian object, the shaving basin has a striking appearance. It was acquired by the museum from a Christie’s auction sale on January 23, 2020. The selection of colors found in the basin follows the classic Imari color pattern of cobalt blue underglaze with iron-red overglaze on a bright white porcelain. It underwent a third firing to include the abundance of semi-translucent gilding found along the rim and throughout the floral motifs spilling into the well of the basin. Figure 1 displays the front view of the object.1 Large flower blooms frame the scrolling floral pattern, both of which are popular motifs in the Imari style. Birds are another traditional Imari motif, but the double-headed bird that appears at the center and top of this basin is distinct. There is a clear difference between the design of the traditional scrolling flowers and the bird, which appears to be a Habsburg eagle, a motif which demonstrates the Chinese potter’s evident understanding of colonial Mexican iconography and taste in ceramic design.2

Fig. 2 Bottom view of the Chinese Imari shaving basin revealing delicate florals, gilding around the rim, and two small holes used for display and other functions. Chinese Imari Shaving Basin (for the Mexican Market). Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum, New York, 2020.

Figure 2 shows the bottom of the basin’s cavetto.3 The shaving basin’s well is filled with a continuation of the scrolling red and blue florals coming out of blue rockwork at the base. The rockwork is another common Chinese porcelain motif that often changes forms, and here it bends to the shape of the well. This design draws focus to the lunular cut out of the bottom lip of the basin. Four large florals are painted there in a more airy fashion. The deep red overglaze of the flowers are bare without traces of the light gilding.

Barber’s basins were relatively unknown objects in China during the late-seventeenth century. They are primarily associated with Europe, and it is possible that Chinese potters created them for display in Mexican homes. It is also significant to note that eagles are an uncommon motif in Asian ceramics, and closer inspection of the bird motif reveals each head to have a resemblance more akin to a duck than an eagle. It was sometimes necessary for the craftsperson to use their own local knowledge when creating imagery on export wares.4 This shaving basin is unique in that the Chinese potters that produced it likely did not understand much about the function of the object or the design of the main motif, yet they still executed it with incredible skill. This was perhaps due partly to the communication exchange along transcontinental trade routes.

The Manila Galleon trade route made it possible for Chinese exports to travel across two oceans to Europe, specifically to Spain, by way of the colonized Americas. This route was one of the first to span three continents, and it allowed for a direct exchange of ideas and designs from Asia to the Americas. The trade route was paramount in the exchange of ceramic and porcelain design, and it helped to solidify Chinese porcelain’s status as a global brand.5 The Habsburg eagle emblem as the shaving basin’s central motif exemplifies this exchange of design influence. We know that a piece with the Habsburg eagle would have likely been made for the Mexican market.

Much of the Chinese porcelain from the Kangxi period was produced in the city of Jingdezhen. From there, the cargoes of porcelain would travel to two major port cities, both colonized by Spain: Manila, Philippines and Acapulco, Mexico. Export wares would travel the arduous journey across the Pacific ocean from Manila and into the Americas by way of Acapulco. Many of the luxury objects traveling from China were intended to continue onward across the Atlantic Ocean and into Spain. However, it is known that many of the coveted porcelain objects stayed behind in colonized Mexico.6 The call for Chinese porcelain in Latin America prompted Chinese potters to design specifically for these markets. The Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494 made this possible by putting Spain at a geographical disadvantage. The treaty favored rival Portugal in granting them access to trade routes along the Indian Ocean. This was a much faster route to receive high-demand Asian goods. Spain was also able to receive Asian exports, but the Manila Galleon trade route required the delicate objects to travel a long distance across both the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans. The exports also had to withstand land travel into the markets of the Philippines and the Americas. The shaving basin’s survival is a testament to porcelain’s simultaneous lightness and durability.

Porcelain’s materiality, in fact, served far better than the textiles that often accompanied them in trade. Several notable shipwrecks document cargos of porcelain traveling the Manila Galleon Trade route. The route’s length caused a lower frequency in cargo shipments; therefore, ships were designed to be as large as possible in order to carry sizeable quantities of textiles and porcelains.7 The volume of objects found on these massive ships serve as important records in understanding international trade. The findings from these wrecks also offer ample evidence and examples of porcelain styles and design. Where other objects, such as textiles, could not withstand the damage from the sea, porcelain’s materiality helps to capture history.

Fig. 3 Detail of double-headed eagle motif on Mexican jar, 1760-80. Jar. Private collection, 1986.

Surviving pieces of porcelain tell many stories. For example, the emphasis on the Imari shaving basin’s Habsburg eagle motif exemplifies cultural exchange impacting design. This is further illustrated by the potters in Puebla, Mexico who were then inspired by the imported Chinese ceramics and would replicate their designs for local use. (See Figure 3 for a Mexican example of the Habsburg eagle motif, a detail of a vase likely produced in Puebla around 1760–1780.8) The scales located on the breast of the bird, the similar form of the wings, and the roundness of the bird’s two heads are highly comparable to the motif in the Imari shaving basin. We can speculate that the Puebloan potters were influenced by Chinese designs based on the timeline of production. However, it is important to remember that Chinese potters were simultaneously producing designs for the Mexican market as well. The effect of these motifs is not one-sided, but rather shared, exchanged, and reproduced in a variety of precious objects representing multiple cultures over several centuries.

The shaving basin, therefore, is more than a utilitarian object or mere display piece. Its iconography underscores the significant role of transcontinental trade in the exchange of ideas and design inspiration. Europe played a major role in the expansion of merchant and market culture that contributed to the rise of globalization, but the shaving basin proves that not all markets centered around Europe. Understanding the relationship between the potters of Jingdezhen and the merchants in Manila and Mexico, and the cultural tastes forming in colonial Latin America, establishes a more polycentric view of history and material culture.

is a writer and researcher of contemporary material culture. She matriculated in the History of Design and Curatorial Studies graduate program at Parsons School of Design with Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum. She is currently an M.A. candidate at the CUNY Graduate Center in Biography and Memoir and works in Access & User Services for The New School Libraries & Archives.

Notes

- Chinese Imari shaving basin (for the Mexican market), front view, 1690-1700, ceramics, porcelain, Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum, New York.

- Jean McClure Mudge, “Manila Galleons to Mexico” in Chinese Export Porcelain in North America. 1st ed. (New York: C. N. Potter, 1986), 49.

- Chinese Imari shaving basin (for the Mexican market), bottom view, 1690-1700, ceramics, porcelain, Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum, New York.

- Meha Priyadarshini, “Introduction: A Global Commodity in the Transpacific Trade” in Chinese Porcelain in Colonial Mexico (Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave MacMillan, 2018), 5.

- Robert Finlay, “Introduction” in The Pilgrim Art: Cultures of Porcelain in World History (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010), 13.

- George Kuwayama, “China in Mexico’s Cultural Heritage” in Chinese Ceramics in Colonial Mexico (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County

Museum of Art, 1997), 13. - Andrew D. Madsen and Carolyn L. White, “Background and Overview” in Chinese Export Porcelain (Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press, 2011), 12.

- Jean McClure Mudge, “Manila Galleons to Mexico” in Chinese Export Porcelain in North America. 1st ed. (New York: C. N. Potter,

1986), 50.