Reviews & Interviews

The Living End by Gregg Araki

Dawson Cole

Still, The Living End. Directed by Gregg Araki. First Run Features, 1992. DVD, 92 minutes.

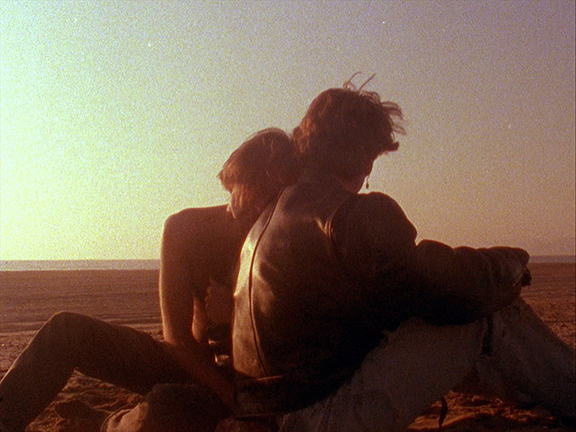

Gregg Araki’s subversive cinematic debut The Living End (1992)1 is often referred to as “gay Thelma and Louise,” but it is much more complex. Residing at the genre intersection of dark comedy, political activism, and star-crossed romance, The Living End follows the story of two destitute gay men in the early 1990s who cross paths after their respective HIV diagnoses. After one of them kills a homophobic police officer, they must go on the run. Filled with gore, passion, and anger, Araki uses this film to express the depression and rage felt within the gay community surrounding the AIDS epidemic. With major themes of hedonism and death, he captures the collective thought of the era and creates a truly harrowing and macabre story of HIV-positive lovers trying to maximize the life and experiences of their numbered days in a nation that has turned its back on them. Araki uses angry, hyper-sexual stereotypes to his advantage, effectively saying, “Look at what you’ve created, America. Look at what you’ve turned us into.” With carefully curated costumes and set design, the director communicates subliminal themes of nihilism, hedonism, and homosexual rage underneath the visage of a 20th-century gay Romeo and Juliet. He achieves this by using symbolic material culture such as frequent skull imagery to represent impending death, costumes that evolve from conservative to provocative as the disease progresses, and blasphemous appropriation of Christian iconography aimed at religious conservatives deserving of blame.

Aside from both being named after the Bible’s gospels, leading characters Jon and Luke are complete opposites. They are two men who would never be together if they were not making reckless, manic-depressive choices in response to their terminal diagnoses, and Araki creates this stark contrast with the design and object choices in the opening shots of each man. Luke is introduced to the viewer while spray-painting “FUCK THE WORLD” in a Southern Californian desert scape, wearing raggedy cut-off clothing and a crucifix on a gold chain around his neck, cigarette hanging from his lips. Jon is seen in an office with slicked-back hair and stylish, if not boring, clothing, making voice memo notes for his steady writing job. Costumes and settings solidify their personalities throughout the film, with Luke consistently embodying the role of a rage-filled, anarchist prostitute who lives by the sword and tries to convert Jon from his existence as a clean-cut member of society. These introductory shots set the tone for Araki’s visual style and make it abundantly clear to the viewer that each character’s clothing represents their world perspectives.

Still, The Living End. Directed by Gregg Araki. First Run Features, 1992. DVD, 92 minutes.

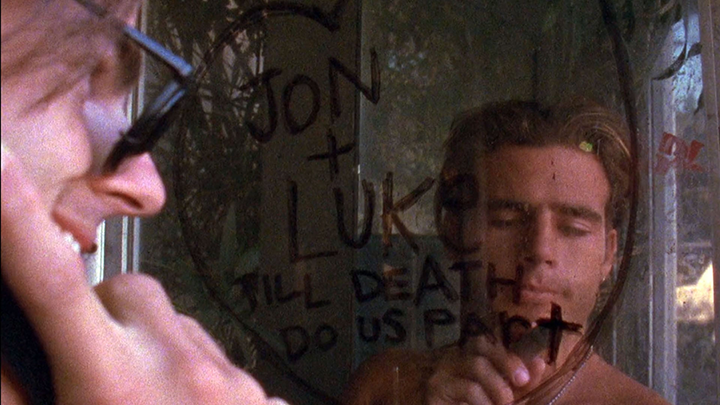

The differences between the two men are underscored dozens of times. Araki pervades the film with examples from Jon preferring romantic sex while Luke prefers BDSM to Jon liking indie music and Luke liking screamo. One stark contrast is when Jon reverts to using his dictation recorder halfway through their road trip, and Luke snaps at him, viciously telling Jon that his job and his hobbies are stupid and that he must let everything go and give into the darkness. By this scene, a breaking point for the two men, they are at the Paradise Motel, an architectural oasis with a serene pool and palm trees. The motel provides a respite from the sad buildings they inhabited in Los Angeles, and it is where Araki illustrates Jon finally giving himself over to the rage and pleasure Luke lives by. It is clear that Jon remains conflicted about whether he is ready to abandon the people from his former life, so Luke adds, “Don’t you get it? We’re not like them – we don’t have as much time. So, we gotta grab life by the balls and go for it.” Here the transformation is complete; Luke’s reckless hedonism is contagious, just like his disease. In the following scene, while making a call to his friend Darcy, Jon is depicted wearing one of Luke’s leather vests with no undershirt, a major shift from his usual cardigan and oversized tee shirts. Darcy is frantic, sensing that something is different about Jon, and pleads for him to return. As indicated by his clothing, however, Jon is too far gone to listen to reason and laughs to reassure her that everything will be okay. While this is happening, he lovingly watches Luke scrawl “JON + LUKE. TIL DEATH DO US PART” on the side of the phone booth. This poignant scene reveals the deadly way the plot will progress, and Araki intentionally saturates the set with design choices that illustrate both past and present. He uses comfort objects from a former life, such as favorite tee shirts and cassettes, to symbolize old hopes and beachy architecture and landscaping to represent safety and solace, while the provocative shift in clothing represents new philosophical and deadly perspectives. The graffiti is the literal “writing on the wall”–a self-fulfilling prophecy to foreshadow what is to come as a consequence of Jon completely giving himself over to Luke.

In addition to his transgressive subject matter, Gregg Araki is cult-famous for his highly stylized and easily recognizable design choices, almost all of which are heavy with symbolism and reflect what he calls his “Teen Apocalypse” style. In The Living End, skull imagery is the most recurring symbol of this technique. In virtually every scene, a skull is present: Luke’s skull earring is visible in the film’s opening shot, a skull sits on the doctor’s desk while he tells Jon he is HIV positive, a woman who attempts to mug Luke wears a skull-patterned scarf, and so forth, finally ending with another shot of Luke’s skull earring. In these instances, the skull insinuates that death is nearby and acts as a memento mori. Every time a skull is visible, Araki is also invoking religious principles. Rather than serving as a reminder that life is short and, therefore, one should live mindfully in light of God’s blessing, Araki uses the skulls to say that life is short because the world has turned its back on the LGBTQ+ community, so everyone should do whatever they want and live as foully as possible until time is gone.

Still, The Living End. Directed by Gregg Araki. First Run Features, 1992. DVD, 92 minutes.

This is only one facet of the greater theme of religious blasphemy that Araki diffuses imagistically throughout the film. Ironically, both men are constantly seen with some form of Christian iconography, either as part of their costume or as a decoration in the mise-en-scene. Jon is often depicted wearing a tee shirt with an image of Jesus, and Bible verses appear throughout the film on billboards, bumper stickers, signage, and even tattoos. However, the clearest example of Araki’s blasphemy is that Luke is always wearing the gold chain with the crucifix, an adornment that appears expensive and conjures images of what his life must have looked like before HIV and prostitution. Towards the end of the film, Luke sheds some light on how difficult his upbringing was and insinuates that he was cut off or abandoned by his family and religion from a young age. Additionally, Jon has a bumper sticker on his car that says, “Choose Death,” while the women who attempt to rob Luke have a bumper sticker that says, “I Love Jesus.” By giving the protagonists nihilistic and inherently anti-religious sentiment but at the same time attaching these antagonists to Christian culture through their garments and accessories, Araki makes clear early in the film that God is dead. The two diseased men are testimony to that. If God was real, his followers would not treat their neighbors with the malice that Christians express toward queer people in the film. Accessories and costumes assert a surreal view of what Christianity amounts to during the Aids epidemic.

Still, The Living End. Directed by Gregg Araki. First Run Features, 1992. DVD, 92 minutes.

There are other fascinating aspects to this film. It is unique, for example, that Araki, a Japanese American man, primarily worked with white actors. As this was his first film to be released to a wider audience than usual, perhaps it made sense to ease the public into a harsh, political critique using the same principles James Baldwin employed when writing Giovanni’s Room.2 Baldwin famously chose to write about white men falling in love because he recognized that to be gay is political and to be black is political; he needed to focus on one of these marginalized groups or no one, he felt, would have ever published or read the novel at all.3 Araki deliberately chose to step outside his own ethnic group by selecting two white, attractive American men as the center of his story about gay men suffering through the AIDS crisis. Perhaps, he felt that by focusing on two white gay men, the movie would be more likely to engage people’s sympathies with the tragedy of AIDS.

In the final scene of the movie, everything shifts. The setting goes from bleak architecture and broken-down cars to a pristine, empty beach. Jon wakes up to find Luke leaning over him, Luke’s crucifix hanging over Jon’s face; With a gun in his mouth, Luke is preparing to end his life while having sex with Jon. Luke says, “Don’t you get it? I love you more than life.” But this is not love – it is a story of parasitic codependency as an extreme reaction to fear. Luke and Jon care about and need each other, but they do not love each other; they use each other as a destructive coping mechanism for grappling with the terrifying eventuality of youthful death. The Living End is a political story of how HIV-positive men were left to handle the weight of their sentences alone while America, charged by conservative religion and bigoted politicians, looked the other way. Gregg Araki uses material culture symbolically to emphasize this harsh truth and bring attention to the psychological and existential effects of society’s ostracization of gay men. The movie is a powerful display of AIDS-era rage delivered by one of the 1990s few openly gay directors who crucially depends on material culture to direct this anger toward evangelical conservatives devoid of true Christian values.

Dawson Cole is a Brooklyn-based student in the MA program in the History of Design and Curatorial Studies jointly offered by Parsons School of Design and Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. His academic interests primarily lie in European design from the 1880s to 1920s, with special attention to the decorative arts and architecture of the French Art Nouveau and to the fine arts of the Vienna Secession. Dawson is also passionate about twentieth-century film, particularly those pertaining to the New Queer Cinema movement like The Living End. Upon graduation, he intends to stay in New York and pursue a career in the gallery sphere.

NOTES

- The Living End, directed by Gregg Araki (First Run Features, 1992), DVD, 92 minutes.

- James Baldwin, Giovanni’s Room (New York: Vintage International, 1956).

- Josep M. Armengol, “In the Dark Room: Homosexuality and/as Blackness in James Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room,” Signs 37, no. 3 (2012): 672.