Design & Activism Issue 5 2021

Sara Little Turnbull, Graduate of the Parsons School of Design, Inspired the N95 Mask

Amanda Forment

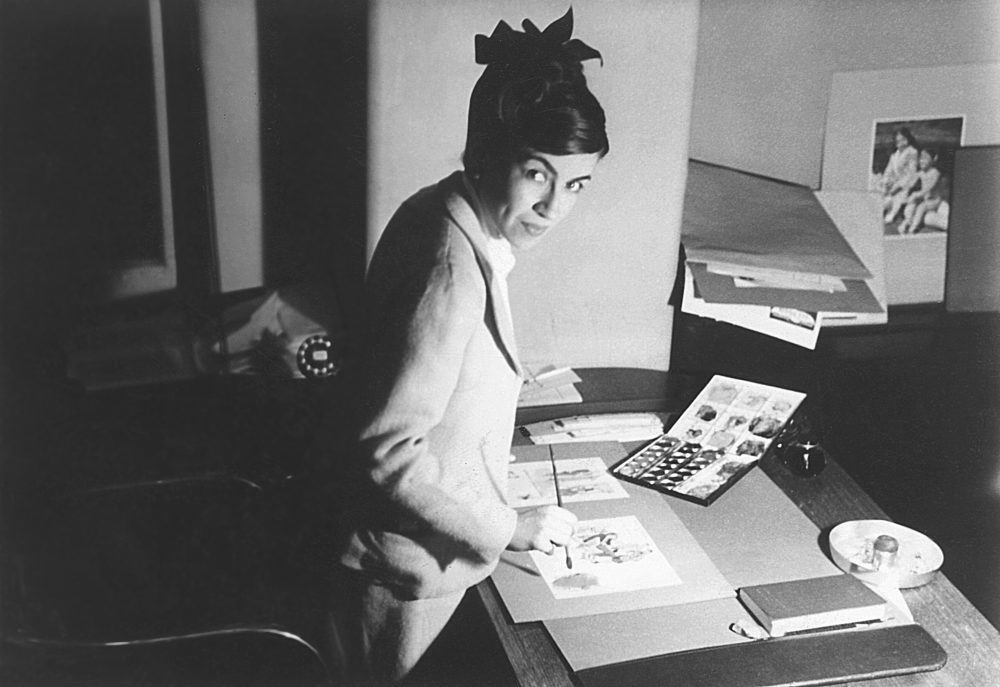

Sara Little Turnbull in her design studio, circa 1940. Photo © Center for Design Institute.

COVID-19 has been a swift-moving catastrophe. Suddenly, people across the globe have been confronted with harrowing death tolls, contagion rates, and a number of previously unfamiliar terms and objects that have come to define daily life during the pandemic. The most pervasive and simultaneously fraught of these is the face mask, with the N95 being the most infamous and acclaimed. The demand for N95 masks jumped from 500 to 1000 percent higher than it was before the pandemic, with massive mask shortages amongst health-care workers consistently dominating the news. Why this sudden rush for N95 masks? This disposable filtering mask is considered one of the world’s most reliable protective tools against viruses. According to the CDC, if an N95 mask is worn properly it is able to “remove at least 95% of airborne particles during ‘worst case’ testing using a ‘most-penetrating’ sized particle.”1 The “95” in the name of the mask refers to this 95 percent particle blocking ability.

Sara Little Turnbull2 (September 21, 1917 – September 3, 2015), one of America’s first female industrial designers, played a key role in developing ideas and details of the N95 masks as we know them today. Raised in Brooklyn in an impoverished immigrant family from Russia, Sara obtained a scholarship from the School Art League of New York City and the National Council of Jewish Women, which allowed her to study advertising design at Parsons School of Design.3 After graduating, she became the décor editor of House Beautiful, a popular interior decorating magazine. Her position at the magazine gave her the power to propose and develop new ideas regarding the American lifestyle and the quotidian objects which constitute it. After almost two decades at the magazine, she went on to establish her own design consultancy firm, Sara Little Design.

Sara Little Turnbull also referred to herself as a cultural anthropologist which informed her user-focused approach to design. One of Sara’s first projects was as a product research consultant for the manufacturing firm 3M. She started in the Gift Wrap & Fabric Division, an area of the company often relegated to women for their ‘feminine’ touch. There she learned about the nonwoven technology that was being used for stiff decorative ribbons. She saw immeasurable potential in this material. This led her to test and experiment, creating products such as the molded bra cup. She found that this nonwoven fabric, given its highly porous and breathable qualities, was ideal for a bra cup that made the overall experience of wearing a bra much more comfortable.

During this time, Sara was looking after three sick family members; her mother, father, and sister were all hospitalized. The extensive amount of time she spent in hospitals helped her notice the impractical flat, tie-on masks doctors and nurses wore in the 1950s. The combination of her design background and personal grief over losing her family inspired her to create a new, improved, and superior medical mask. The molded bra cup she had been contracted to design became one of the driving forces of inspiration behind her medical mask. By 1961, 3M patented a mask based on Sara’s design. The mask had the same bubble shape as the molded bra cup, but it included additional features such as a bendable nose clip and an elastic tie to fit it into place. It was also disposable. The first iterations of the mask, however, had several problems. It was discovered that pathogens were getting past the nonwoven material. This prompted the company to rebrand it as a dust mask. In the 1970s, the Bureau of Mines and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health created the first criteria for what is known as ‘single-use respirators.’ Under these new guidelines, 3M produced the first single-use N95 dust respirator in 1972. This improved mask is remarkably similar to the one we still use today—almost five decades later. Yet, few know about its designer Sara Little Turnbull.

The pandemic has presented new design challenges as we strive to protect ourselves, our loved ones, and some sense of normalcy in our daily lives. Sara Little Turnbull’s holistic and creative designs, as well as her emphasis on user experience of the object, can serve as inspiration for how designers can meet the demands of these current times.

is a student in the History of Design and Curatorial Studies MA program at Parsons School of Design and is a curatorial fellow in the Contemporary Design Department at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. She is particularly interested in the material culture of Latin America.

Notes

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Approved Respirators, What Are They?” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, January 29, 2018.

- Center for Design Institute, “About Sara Little Turnbull,” accessed April 26, 2021.

- Paula Rees, “Sara Little Turnbull,” National Women’s History Museum, accessed April 26, 2021.