Objects

On Peg Averill’s Stop Militarism in Our Schools!

Chloe Buergenthal

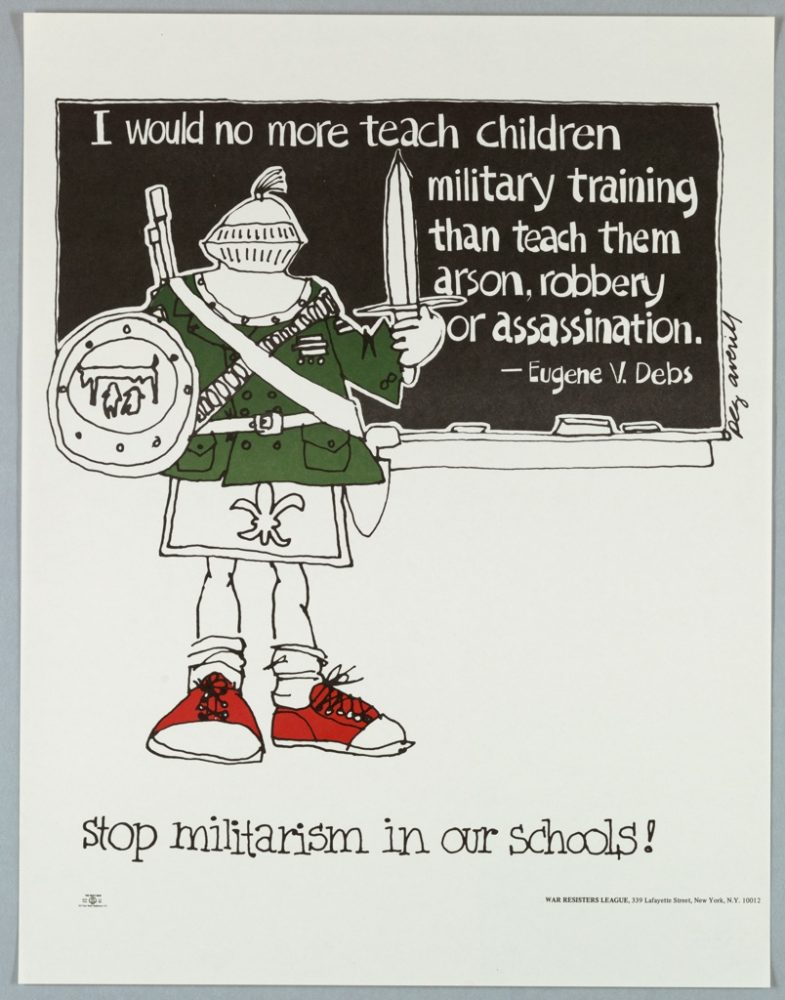

Fig. 1 Poster, Stop Militarism in Our Schools!; Designed by Peg Averill; USA; lithograph on paper; 56 × 43.3 cm (22 1/16 × 17 1/16 in.); Gift of Steven Heller and Karrie Jacobs; 1993-53-70 (Cooper Hewitt)

The simplicity and coyness of Peg Averill’s War Resisters League commissioned poster, Stop Militarism in Our Schools!, is both compelling and easily understandable. Upon first glance, the focal point of the image successfully draws in onlookers through the bold flash of red on a central figure’s Converse-style tennis shoes. Composed of a thin, quick-feeling, and sketchy black outline, the figure sits slightly askew, creating their body’s modest recline onto the chalkboard floating in the background. Wearing sneakers atop a pair of sagging and wrinkled mid-calf socks, they also sport a classical-style kilt or sash around their waist that rests slightly above the knee. An understated fleur-de-lis symbol referencing the French monarchy sits centered atop it, devoid of any details or shadowing.

Across their chest is a modern military jacket in classic army green with two crisscrossed straps extending over their clavicle and behind their back. One holds a long shafted gun against the figure’s backside, while the other is decorated with a round of ammunition. The figure also wears a standard military uniform belt, medals, and ornaments of honor, while also displaying a holstered handgun at the hip. In the figure’s hands sit a shield and a sword, framing the modern military top. A classically derived battle helmet and neck protector rest nonchalantly atop their jacket. The antiquity of the clothing’s design and accessories are clear in the metal studs along the rim, the tuft of fibers emerging from the helmet’s crown, and the closed metal eye/face covering. The shield also features highly simplified Roman imagery of a she-wolf nursing the founders of Rome, Romulus, and Remus. This figure’s gender and race are indiscernible given a limited color palette and their use of a face-covering, which allows onlookers of all socially constructed identities to connect with and to the figure.

The black chalkboard the figure attracts attention towards is the largest section of solid ink in the entire design. It sits slightly below the top edge of the print and covers about a third of its surface. At the same height as the soldier’s waist is a ledge with two pieces of chalk and an eraser. Alluding to the figure’s equal convenience and ease in their ability to reach for either, the butt of the figure’s handgun is the same height as the chalk they stand next to. The chalkboard reads: “I would no more teach children military training than teach them arson, robbery, or assassination -Eugene V. Debs.” Debs was a notable socialist, anti-war activist, and trade unionist, as well as a five-time U.S. presidential candidate nominated by the Socialist Party of America.1 The thickness of each sans-serif letter varies slightly from those it sits between, evoking a child-like feeling. To the board’s right is a cursive signature that reads “peg averill.” Unlike the blackboard’s text, the signature feels authentic, as if written by a real hand. In all lowercase and cursive letters, it is the most casual aspect of the entire piece.

Towards the bottom of the poster is the emblem for “THE PRINT SHOP,” the text “WAR RESISTERS LEAGUE,” and each of their respective addresses. The Print Shop’s emblem also includes its union identification number, “I.U. 450,” and the words “Union Shop.” WRL is also no longer located at 339 Lafayette, and the space is instead occupied by streetwear brand Kith, just in case readers are curious about capitalism’s effects on social change and collective action.

While a visual analysis of the image and its narrative hold substantial values of their own, the object’s medium and physicality are also significant. The object itself is about an arm’s length, 22 1/16 × 17 1/16 inches or 56 × 43.3 cm, and is printed on semi-thick paper. Its size makes it effective in terms of the convenience of its circulation. As evident by its unfaded white color and the lack of any apparent blemishes or creases from past handling, its condition is pristine.

As one work from a series of around seven graphics that artist and activist Peg Averill created for the War Resisters League, or WRL, this and Averill’s other designs functioned as both a fundraising tool and a way to signal the issues that the movement/organization believed to be of importance.2 WRL was founded in 1923, and, at the time of Averill’s poster design, described themselves as “advocates [for] Gandhian nonviolence as the method for creating a democratic society free of war, racism, and human exploitation” who “[saw] war to be a crime against humanity.”3

Originally from Akron, Ohio, Averill lived in Washington, D.C., and Baltimore, Maryland before moving to New York.4 While in D.C., she helped found a typesetting and graphic design collective called ‘Art for the People’ followed by her membership at Jonah House Collective in Baltimore, a faith-based organization that engages in nonviolent resistance against war and supports the banning of weapons of mass destruction.5 Like WRL, the Jonah House Collective is still an active organization. Alongside her work in the peace and anti-war movement, Averill worked professionally as an Art Director at Rolling Stone while residing in New York before moving back to Ohio to raise her daughter.6 Alongside WRL, Averill was also an active member of the nonviolent affinity group “NYC 339” and was even arrested during the Seabrook Occupation of 1977.7 Although her dedication to the anti-war and peace movements can be seen most prominently by way of posters and graphics when surveying her life, which was cut short by a sudden heart attack in 1993 at only 44, Averill was also an intelligent and poignant writer.8 Alongside her contributions to the War Resisters League’s protest art and nonviolent actions, she also served as a WIN Magazine staffer and contributed to a variety of other movement publications, including The Nonviolent Activist and The Liberation News Service.9

No formal agreement regarding the series of works Averill created for WRL was made according to League staffers who were present at the time of their composition.10 Longtime WRL member Ed Hedemann has also proposed the publication date of this poster to have been in 1978 instead of c.1970, as it has been labeled in Cooper Hewitt’s collection.11 While the exact price this object sold for is undetermined, the majority of WRL publications and materials were sold for under three dollars.12 Given its presumably low price point and the ease of its physical mobility, the object is an ample example of how WRL and the anti-war/peace movements used protest art to communicate their ideologies.13 Its temporal closeness to the end of the Vietnam War also makes it an extremely relevant document, as it acts as evidence of the counter-hegemonic ideals that protest art was often responsible for promoting during the period.

Although clearly propelling WRL-sanctioned ideals, I believe that Averill has made explicit choices in the poster’s design to push forward other counter-cultural beliefs that were growing in momentum at the time of its production. These existed beyond WRL, and most notably included the promotion of gender equality and socialism. The design choices Peg made to promote these beliefs include her selective mention of Eugene V. Debs, the androgyny of the figure, and the poster’s iconography.

Averill was not alone in these decisions, as protest art was a prominent fixture within WRL and other social justice movements/publications.14 As a result of and in response to the United States’ participation in the Vietnam War (1955-1975), a large variety of artist-activist groups formed parallel to social justice organizations to collectively stand against the government, engage in societal issues, and protest their treatment/role within the fine art world. The formulation of such groups, most famously the AWC (Artist Workers Coalition) and those like the Artist and Writers Protest against the War in Vietnam and Guerilla Art Action Group, contributed greatly to the shift in the role that artists and (protest) art played in social change and activism.15 Partially due to the growing art world, the newfound understanding of the power of pictorial narratives, and the importance of purposeful art, protest art became increasingly prevalent and significant.16

In addition to posters like Stop Militarism in Our Schools!, WRL themselves also created, sold, and circulated a variety of other materials. These included annual Peace Calendars (beginning in 1955), newsletters, flyers, leaflets, and other small items like pins and paper ornaments.17 Peace Calendars, alongside WRL’s poster production, used art particularly voraciously to engage organization members/movement supporters and to promote anti-war ideals. Each page included an artwork, a quote or writing from an activist or scholarly text, and a calendar page.18 Sadly, WRL stopped producing annual calendars in 2012.19

Even still, despite what may appear as impressive liberalism concerning the movement’s publications and promoted artworks, and how presumably forward-thinking groups like WRL may have labeled themselves, the period should not be forgotten as having held white cis men in the utmost esteem. The term intersectionality, originated only in 1989 by Kimberly Crenshaw, refers to the sociological lens through which class, race, gender, and other forms of social or societal stratification intersect and overlap with each other.20 At these intersections and overlaps, unrest, discrimination, and power imbalances emerge. WRL and other organizations were no exception to the vices of white straight cis manhood and their impacts on those with less social capital and control. The effects of intersectionality, and the broader cultural attitudes towards women within the 60s and 70s, must be understood as having impacted Averill’s lived experience, her role as a protestor and artist, and the analysis of her work as an agent of intersectional social justice and anti-war ideals.

Wendy Schwartz, who was heavily involved in WRL and the peace movement as a whole, and knew Averill personally/professionally, claims intense factionalism within the peace and anti-war movements. She asserted the existence of significant divides between different sects or beliefs among protestors and organizers despite their overlapping goals.21 According to Ed Hedemann, there was also considerable hesitation regarding WRL officially participating in actions or supporting other social issues, as many often feared that they would distract, or even weaken, their anti-war message. For instance, there was a disagreement concerning whether or not the official adoption of an anti-nuclear weapon stance was too far outside the scope of the War Resisters League’s core tenet.22

Edited by Wendy Schwartz, WRL’s 1972 calendar, “In Woman’s Soul,” is “A selection of statements and artwork by women on peace and social justice,” as stated by its cover page, and was named for a quote by feminist and leftist Emma Goldman. The original quote claims equal rights and suffrage to begin in/from “woman’s soul.” Selling for only $2.25, “In Woman’s Soul” took on a variety of topics alongside its promotional and fundraising purposes. In this edition, artwork and quotes were selected by and from only women concerning the topics of peace and social justice.

In its dedication, Schwartz discusses the contemporary realities facing women in the 1970s. She writes, “[women] can offer ideas as well as we can take notes- our Pavlovian conditioning to answer ringing phones shouldn’t prevent us from making [policy] too… in the past, many of our contributions to the movement have been minimized or ignored, consciously or unconsciously, by the men who assumed leadership roles.”23 In the calendars forward, writer and peace advocate Ann Morressett Davidon even thanked the “skeptical male staff of WRL” in her closing statement. Given Schwartz’s dedication and Davidon’s comments, as well as the plethora of quotes and issues touched upon within each spread, the awareness of women within the peace and antiwar movements as being undervalued/sold short, and women’s larger status as that of secondary to men, was (and is) plainly explicit.

The keen awareness of inequality is (literally) illustrated again in Averill’s cover for WIN on September 23, 1976, and her 1975 Art for the People poster, where she depicts Susan Saxe, a top 10 fugitive on the FBI’s Most Wanted. Saxe participated in a 1970 bank robbery in Massachusetts to “fund revolutionary activities,” and was arrested in 1975. A member of the so-called ‘radical student movement’ at Brandeis University, her open identification as a lesbian, made her evasion authorities and the news of her arrest well-known and hotly contested. Averill additionally used Saxe’s name as part of the text forming the female gender pictograph on a Women’s Day poster she designed in 1976. This promotion of Saxe’s case and the support Averill believed her to be entitled to from the anti-war/women’s movements are further proof of the ability of protest art and org publications to participate meaningfully in the circulation of leftist ideas. It also further clarifies such works’ ability to act as vessels for artists’ personal beliefs.

In Stop Militarism in Our Schools! Averill’s choice to highlight notable socialist Eugene V. Debs promoted socialist beliefs that would’ve been non-hegemonic to 1970s culture and different from sanctioned WRL ideals. Her use of such a character was notable given Debs’ understanding of societal problems as being caused by economic ones, and thus his promotion of the condemnation of capitalism.24 Averill’s explicit design choices appear to emphasize this and other often-forgotten intersectional WRL issues. While her mention of Eugene V. Debs is easily discernible as a way to promote socialist ideals and support union organizing, the inclusion of Romulus and Remus and the fleur de lys would have been less known to the layperson or org member.

The origin story of Rome rests on its ancient claim that the raising of its two founders, Romulus and Remus, was carried out by a she-wolf who took them in and nursed them as if they were cubs. In its original Latin, the word she-wolf, lupa/lupae, also means prostitute and is gendered female. The other symbol, a fleur de lys, denotes the French monarchy, by which the birth of a male heir was necessary for families to maintain their power and right to rule. Not only were both of these powerful cultures reliant on women for their underlying success, but they also consisted of extreme gender inequality and brutal violence. Therefore, we can suspect Averill chose this iconography specifically for their historical connotations.

Although likely that the figure’s lack of skin tone was to maintain low print costs, given the amount of ink it would have required, their gender ambiguity may have been intentional. The suggestion of the purposefulness of Averill’s choices could be supported by her active role in the women’s liberation movement and self-identification as a feminist, which points to her desire to see and promote women as capable and equivalent to men in all representations and situations. Based on these reputed symbols referencing gender equality/women’s rights and the promotion of socialism, Averill’s poster indicates how art objects can spread counter-cultural ideals while also promoting their acceptance and adoption. Its function as a poster also allows for its easy dissemination and mobility.

In all, Stop Militarism in Our Schools! is an example of the physical and figurative circulation of WRL/anti-war and peace movement beliefs and the ways in which protest art has historically acted as an agent of counter-cultural/non-hegemonic idea exchange.25 As noted by Julia Bryan-Wilson, the “artistic and political ruptures” of the 1960s led to a time of “political turmoil [in which] … art… [was] ruthlessly redefined and reorganized.”26 Art has also been theorized to function as a reflection of class interests and relationships.27 Therefore, Averill’s design, and the anti-war and anti-violence sentiments discernable from it, are reflections of the counter-cultural ideas that gained prevalence within the contemporary socio-political landscape of the 1970s. The understanding of protest art that emerges through the contemplation of Stop Militarism in Our Schools! provides great insight into both its contemporary culture and the historical relevance of protest art.

Originally from Baltimore, Maryland, Chloe Buergenthal has been fascinated by the visual arts and the stories behind their makers since an early age. As a current MA candidate at the MA program offered jointly by Parsons School of Design and Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, their most recent research surrounds non-heteronormativity and ‘intimate friendships’ between nineteenth-century women and Robert Arneson’s Funk Ceramics and TB9. A graduate of Muhlenberg College, Chloe double majored in Sociology and Studio Art (sculpture concentration). They are most interested in the American craft movement, the interwar period, and investigating the missteps of canonical, white, heterotypical scholarship and institutions.

- “Eugene V. Debs: American Social and Labour Leader,” Britannica, last modified November 1, 2022, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Eugene-V-Debs.

- Ed Hedemann, Interview by Chloe Buergenthal. October 31, 2022.

- War Resisters League Calendar Collective, In Woman’s Soul: 1972 Peace Calendar (War Resisters League, 1972), 1.

- Ed Hedemann, email to author, October 28, 2022.

- Ed Hedemann, email to author, October 28, 2022.

- Wendy Schwartz, Interview with Chloe Buergenthal. October 28, 2022.

- Ed Hedemann, email to author, October 28, 2022.

- Murray Rosenblith, “Peg Averill 1949-1993” in The Nonviolent Activist, November-December 1993, 22; Peg Averill, “Thoughts on Nevelson,” Great Speckled Bird 7, no. 31 (July 31, 1974): 1-3.

- Murray Rosenblith, “Peg Averill 1949-1993” in The Nonviolent Activist, November-Decemeber 1993, 22; Peg Averill, “Thoughts on Nevelson,” Great Speckled Bird 7, no. 31 (July 31, 1974): 1-3.

- Ed Hedemann, Interview by Chloe Buergenthal. October 31, 2022.

- Ed Hedemann, email to author, October 28, 2022.

- War Resisters League, Handbook for Nonviolent Action (New York and Connecticut: War Resisters League and Donnelly/Colt Graphix, 1989); “Lessons of the Coal Strike: The Coal Strike Ends: the Struggle Continues: Generating Power for the People, Israel Notebook,” WIN: Peace & Freedom Thru Nonviolent Action, April 27, 1978, https://digitalcollections.tricolib.brynmawr.edu/object/sc266978; War Resisters League 1972 Calendar Collective, In Woman’s Soul: 1972 Peace Calendar (War Resisters League, 1972), 1.

- Jen Hoyer and Nora Almeida, The Social Movement Archive (California: Litwin Books, 2021), 134-145.

- Wendy Schwartz, Interview by Chloe Buergenthal. October 28, 2022; Ed Hedemann, Interview by Chloe Buergenthal. October 31, 2022.

- Scott H. Bennett, “Present at the Creation: The WRL, Direct Action, Civil Disobedience, and the Rebirth of Peace and Justice Movements, 1955-1963,” in Radical Pacifism: The War Resisters League and Gandhian Nonviolence in America, 1915-1963 (New York: Syracuse University Press, 2003), 204-238.

- Alain Beiber, Robert Klanton, Alonzo Pedro, and Krohn Sike, Art and Agenda: Political Art and Activism (Berlin: Gestalten, 2011); Jen Hoyer and Nora Almeida, The Social Movement Archive (California: Litwin Books, 2021), 134-145.

- Jen Hoyer and Nora Almeida, The Social Movement Archive (California: Litwin Books, 2021), 134-145.

- Wendy Schwartz, Interview by Chloe Buergenthal. October 28, 2022; Ed Hedemann, Interview by Chloe Buergenthal. October 31, 2022; War Resisters League Calendar Collective, In Woman’s Soul: 1972 Peace Calendar (War Resisters League, 1972).

- “Vintage WRL Peace Calendar,” War Resisters League, https://www.warresisters.org/catalog/vintage-wrl-peace-calendar.

- Kimberle Crenshaw, “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color,” 1296.

- Wendy Schwartz, Interview by Chloe Buergenthal. October 28, 2022.

- Ed Hedemann, Interview by Chloe Buergenthal. October 31, 2022.

- Calendar/Appointment Book, In Woman’s Soul: 1972 Peace Calendar; War Resisters League; USA; 22 x 5 ⅜ cm. Collection of Chloe Buergenthal.

- Morgan H. Wayne, “The Utopia of Eugene V. Debs,” American Quarterly 11, no. 2 (1959): 120–35, https://doi.org/10.2307/2710669.

- Scott H. Bennett, “Present at the Creation: The WRL, Direct Action, Civil Disobedience, and the Rebirth of Peace and Justice Movements, 1955-1963,” in Radical Pacifism: The War Resisters League and Gandhian Nonviolence in America, 1915-1963 (New York: Syracuse University Press, 2003), 204-238; Matthew Israel, “Kill for Peace: American Artists Against the Vietnam War,” Erenow, accessed November 2, 2022, https://erenow.net/ww/kill-for-peace-american-artists-against-the-vietnam-war/4.php; Julia Bryan-Wilson, “The Vietnam War Era,” in Art Workers: Radical Practice in the Vietnam War Era, (California: University of California Press, 2009), 9-39; “A Brief History of Protest Art From the 1940’s until now- in Pictures,” The Guardian, September 6, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/gallery/2017/sep/06/a-brief-history-of-protest-art-from-the-1940s-until-now-whitney-new-york; Karrie Jacobs and Steven Heller, Angry Graphics: Protest Posters of the Reagan/Bush Era” (Utah: Peregrine Smith Books), 1-12.

- Julia Bryan-Wilson, “The Vietnam War Era,” in Art Workers: Radical Practice in the Vietnam War Era, (California: University of California Press, 2009), 36.

- Cesar Grana, “On the Contradictions of Ideas in Marxian Philosophy of History,” in Meaning an Authenticity: Further Essays on the Sociology of Art (New Jersey and Oxford: Rutgers- The State University and Transaction Publishers, 1989), 98-99.