Issue 5 2021 Short Essays

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and the Lace Collar

Laura Erdos Fernandez

Fig. 2 Needle-made lace cravat end (one of two), France or Netherlands, 1695-1699. Linen, 10.5 x 19.25 in. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, Accession number 1962-50-18a.

Fig. 1 Frans Pourbus the Younger, Portrait of Margherita Gonzaga, 1603. Oil on Canvas, 36 ½ x 27 1/4 in. Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

The year 2020 saw the unfortunate passing of Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg (March 15, 1933—September 18, 2020). Justice Ginsburg received her B.A. from Cornell University and attended Harvard Law School before receiving her LL.B. from Columbia in 1959. Across her distinguished career, Justice Ginsburg served as a Professor of Law at Rutgers University School of Law and at Columbia Law School. In 1980, she was appointed to the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, and in 1993 President Clinton nominated her as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court. As a Supreme Court Justice, Ruth Bader Ginsburg incorporated lace collars, or jabots, into her judicial wardrobe, creating a striking juxtaposition of white against the long and flowing black robes traditionally worn by judges in the United States. While the late Justice Ginsburg’s legacy inevitably reflects her tireless work and advocacy for gender equity, her choice of lace jabots and collars was equally memorable and remains an iconic part of that legacy. By choosing to wear lace in what had been a male-dominated space, Justice Ginsburg demonstrated that women could be both feminine and substantive.

Lace was first painted with great fidelity in the sixteenth century when it appeared on clothing as collars, ruffs, and cuffs.1 Popular across Europe, with large lace making centers in France, Italy, and Flanders, it was initially and primarily worn by wealthy men and women as decorative adornment. In the portrait of Princess Margharita Gonzaga of Mantua (1605) (Fig. 1) by Frans Pourbus (the Younger) in the collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the dissonant, oversized, and impressively upright lace collar contributes to the interpretation of the character by suggesting pride, strength of opinion, and strong virtues. In portraits, Shakespeare is often depicted wearing a shirt with a large, elaborate lace collar over a jacket covered by a robe. Bobbin-style lace is mentioned in his sixteenth-century play Twelfth Night—“And the free maids that weave their thread with bones”2—which references the act of weaving threads with bobbins “bones” to form lace patterns.3 The size and embellishment of the lace ruff worn by the sitter in seventeenth-century Dutch portraiture signified social and political status. And in eighteenth-century France one can find an abundance of narrative content in the lace designs. The ends of a cravat could articulate the importance of the king, court etiquette, and sociability, among other cultural meanings. As illustrated here (Fig. 2), a central figure dressed as an emperor-like warrior, holding a Roman baton and wearing a helmet of a double-headed eagle associated with the Roman Empire, pays homage to France’s sixteenth-century conquest over the Kingdom of Naples. Two kneeling warriors in feathered headdresses flanking the central figure also suggest France’s trade with the four continents and reference France’s political connections to West Africa.4 The scene is topped by a French royal crown further legitimizing the power and authority of the king.

The Cravat v. The Jabot Portraiture reinforced the importance of textiles to setting the scene for the political and social extravaganza that was expected at royal court. The cravat, a seventeenth century version of a necktie, was typically worn when in attendance at such events. The arrangement of the cravat required two rectangle ends sewn into the middle section of plain fabric. The fabric was wrapped around the neck and joined in the front, so the lace could be displayed. When joined with another cravat end, the two ends create a shape conducive to the gathering and display of figurative elements. Lace of this caliber was costly and worn by fashionably dressed men of nobility and stature. The prestige of the lace cravat really lies in its intimate iconography and imagery which was intended to gratify the owner by displaying such charming details to one’s social circle. By the end of the seventeenth century, the lace collar was replaced by the jabot, or “laced band,”5 worn by both men and women. A jabot—equivalent to a seventeenth century gentleman’s tie—is a frill of lace, ruffle, tulle, or chiffon, fastened at the neck or hung over the front of a shirt or jacket. It is from the French word for a bird’s “gizzard” and was originally a male clothing item, dating to the middle of the seventeenth century. “Jabot” is now also used to describe a decorative neck frill on women’s dresses or an ascot in men’s formal attire. ♦

By the turn of the nineteenth century, however, machine-made lace made its use as a decorative accent more widely accessible across social classes. While historical research shows that lace was a fashion choice popular among both men and women, the lacemaking tradition itself is more often assigned to female craftspeople. Due to the time-consuming nature of lacemaking initially by hand, women presented an inexpensive labor force, increasing profits for those manufacturing and selling lace on the consumer market. Early artistic references to female lacemakers can be found in paintings such as Johannes Vermeer’s The Lacemaker (1669-1670) in the collection of the Louvre Museum in Paris.

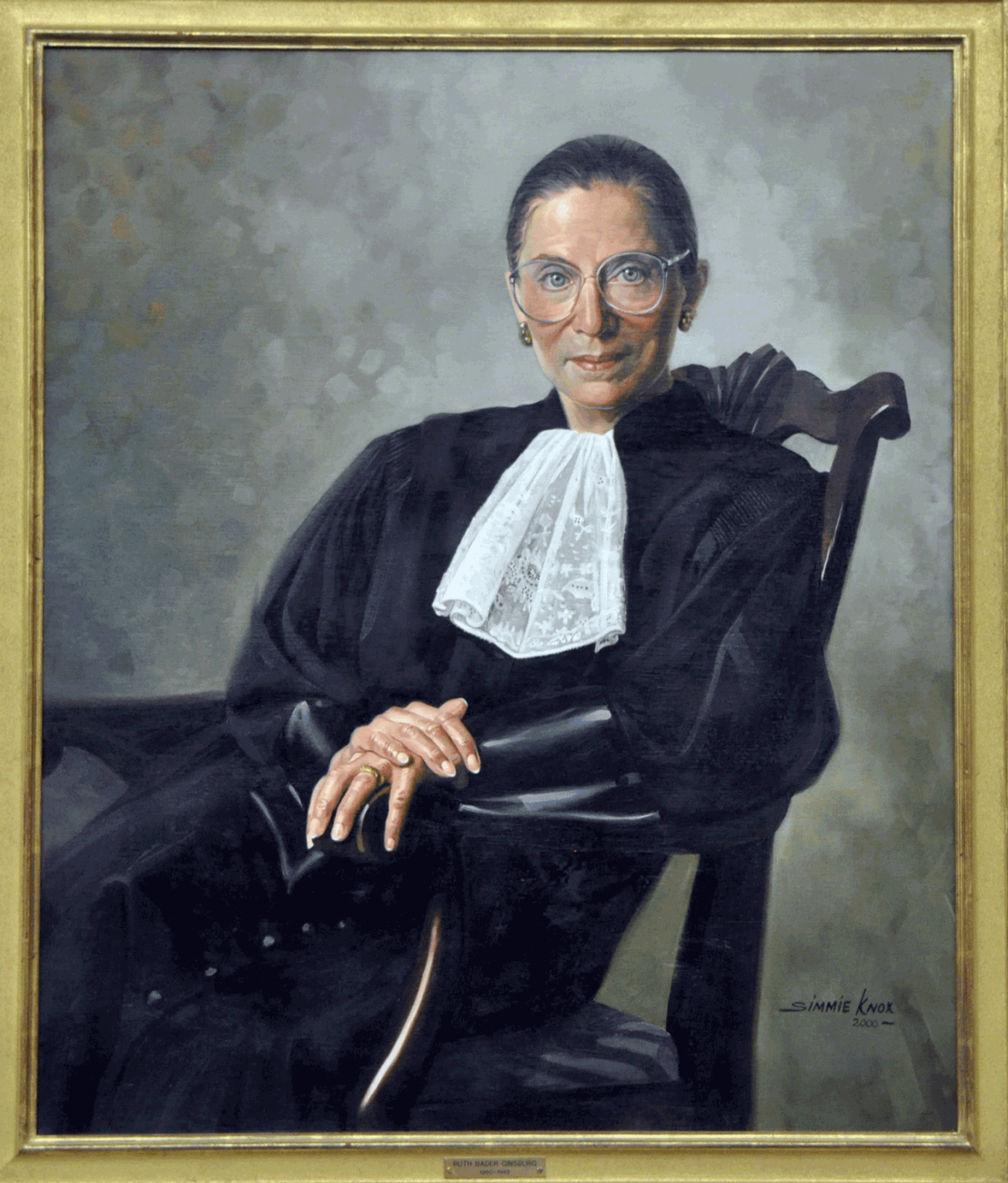

Fig. 3 Simmie Knox, Portrait of Ruth Bader Ginsburg, 2000. Oil on Canvas, 38.5 x 32 in. Courtesy of Historical Society of Washington DC, Carnegie Library.

Considering the history of lace—particularly as it is intertwined with female laborers or multitudes of under-recognized women working in silence over centuries—Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s preference for the decorative accessory becomes more fascinating. In the United States Supreme Court, traditional black judicial robes are, surprisingly, not a required uniform. In a 2013 Smithsonian Magazine article, Sandra Day O’Connor, the first female justice to serve on the United States Supreme Court, discussed the origin of judicial robes dating back to colonial England where the tradition of wearing both robes and wig headpieces remains today. Contemporary American judges have retained the use of robes as courtroom attire but have abandoned the wigs. However, female justices pronounce their identity within the robes—often by wearing lace.6

Upon her ascension to the bench, Justice Ginsburg, together with Justice O’Connor, began wearing jabots and decorative collars as a strong accent to their black judicial robes that would stand out in portraiture. In both her first official court portrait of 1993 (Fig. 3), and in a group portrait alongside Sandra O’Connor, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan (Fig. 4), various iterations of lace collars and jabots can be seen. As Justice Ginsburg discussed in a 2009 Washington Post article, “‘You know, the standard robe is made for a man because it has a place for the shirt to show, and the tie,’ she said. ‘So Sandra Day O’Connor and I thought it would be appropriate if we included as part of our robe something typical of a woman. So I have many, many collars.’”7 Much the same as a male justice’s choice of tie and dress shirt peeking through black judicial robes, the jabots and collars presented the female justices the opportunity for creative and personal expression within the confines of traditional male judicial attire.

Fig. 4 Justices from top to left: Sonia Sotomayor, Elena Kagan, Sandra O’Connor, and Ruth Bader Ginsburg. All wear different neckpieces that reflect their preferences. Nelson Shanks, The Four Justices, 2012. Oil on canvas, 9 ft. 6 in. x 7 ft. 9 in. The National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. Gift of Ian M. and Annette P. Cummings. © Estate of Nelson Shanks.

Justice Ginsburg’s jabots were carefully chosen and known to represent her stance on the opinions rendered by the court and her unique role in their evolution. Certain jabots, for example, were selected when she issued majority opinions; her softer crochet collars with yellow and cream threads and crystals channeled her approval. Contrastingly, when she dissented she wore “dissenting collars,”8 ones of metal, much like gauntlets used as armor similar to those worn by Joan of Arc; they symbolized struggle or the desire to challenge or to confront. She periodically wore a simpler white jabot of softer weaving with beads acquired in her travels to Cape Town, South Africa or a Belgian-lace collar with Ethiopian drop opals and geometric beading, signifying civil rights and working-class cultures. Indeed, when Justice Ginsburg celebrated twenty-five years on the Supreme Court in 2018, Columbia University Law School presented her with a lace collar commissioned from Elena Kanagy-Loux, a founder in 2016 of the Brooklyn Lace Guild. The design incorporates the number “25” circling the collar.

In earlier centuries, sumptuary laws related to ‘finery’ were enforced by noblemen that made it illegal for European peasants to wear lace. Leadership qualities, however, are not passed through bloodline nor are they delimited to any gender, race, or ethnicity. Justice Ginsburg wore lace, and its intricacy and history as a craft communicated the complexities of adjudicating in a democracy. As Thomas Wright wrote in 1601, “Extraordinary apparel of the bodie declareth well the apparel of the mind.”9

is a student in the History of Design and Curatorial Studies MA program offered jointly by Parsons School of Design and Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. She also holds an MA in Visual Arts Administration and Museum Studies from New York University. She is currently researching her MA thesis on the uses of French and Flemish large-scale lace in European domestic and ecclesiastical interiors of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Notes

- “Lace: A Sumptuous History.” SFO Museum, 2014.

- William Shakespeare, Roger Warren, and Stanley Wells, Twelfth Night, Or, What You Will. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998) Act 2, Scene 4.

- N. Hudson Moore, The Lace Book (New York: Frederick A. Stokes Company, ed. 2019) 174.

- Guy Walton, Louis XIV’s Versailles (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986), 114.

- Hudson, The Lace Book, 175.

- Sandra Day O’Connor, “Justice Sandra Day O’Connor on Why Judges Wear Black Robes,” Smithsonian Magazine, 2013.

- Robert Barnes, “Justices Have Differing Views of Order in the Court,” Washington Post, September 4, 2009.

- Chloe Foussianes, “Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s Collars Decoded: What Each Neckpiece Means,” Town and Country Magazine, September 19, 2020.

- Thomas Wright, The Passions of the Mind (London: Valentine Simmes, 1624), 37.