Reviews & Interviews

How the Hewitt Sisters Made a Museum of Design: The Early Collections, 1895–1930

Margery Masinter and Matthew J. Kennedy

Fig 1. Photograph, Sarah Cooper Hewitt reproduction. Collection of Edward Parmee. s-e-3432. Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum.

Growing up in Gilded Age New York, Sarah (1859–1930) and Eleanor (1864–1924) Hewitt were educated, imaginative, social—and enterprising. In 1895, they realized their childhood dream and opened the Cooper Union Museum for the Arts of Decoration (Fig. 1 and 2). Their mission was to educate and inspire American artists and designers at Cooper Union, a free school for men and women founded in 1859 by their grandfather Peter Cooper. Modeling their museum on the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, the first collections consisted of what the French call “documents” of design, and, like the Paris museum, the sisters also established a reference library and a resource collection of design scrapbooks. They viewed the museum as “a practical relation to the artistic trades,” providing access to design objects for American artists and designers.

Indeed, in 1919, Eleanor would deliver a paper entitled “The Making of a Modern Museum” to the Wednesday Afternoon Club, a club of society and literary women established in 1888. With great flair, she recounted the early history of the Cooper Union Museum for the Arts of Decoration and described how and why it was “modern”. The museum’s modernity, as described by Eleanor, was reflected in its use: it was an active laboratory of decorative arts and design where objects were meant to be handled and studied and not simply contemplated.

Fig. 2 Photograph, Eleanor Garnier Hewitt reproduction. Collection of Edward Parmee. s-e-3433

The Hewitt sisters’ first acquisition as collectors, in 1887, consisted of sixteenth and seventeenth-century textile fragments “purchased at auction, purely for their own pleasure” from the James Jackson Jarvis collection. By 1896, however, The Cooper Union Annual Report lists a variety of gifts to the museum: several collections of “old” brocades and lace; seventeenth and eighteenth-century drawings; illustrated books; designs for monograms and coats of arms; eighteenth-century watercolors and paintings of French interiors; and other “documents” of design. Wealthy friends and family contributed to these early collections, including engravings by Albrecht Dürer and Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn from Peter Cooper’s nephew, George Campbell Cooper. Eleanor recollected, “Poor Mrs. Hewitt [her mother] suffered the most, and as she looked about her devastated home, would often say, ‘I wonder where that is?’ or ‘didn’t I have something like that’ thinking she recognized some cherished object in her daughters’ museum.” The hard-working sisters enlisted loyal friends as volunteers to compile material for scrapbooks, to arrange and document objects, and to perform a myriad of other tasks.

Fig. 3 Photograph, Students Studying the Collection, Cooper Union Museum for the Arts of Decoration, reproduction. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. s-e-3455.

“Then came a wonderful series of happenings,” wrote Eleanor. In 1907, the philanthropist and collector George A. Hearn formed the Council for the Museum, composed of philanthropists, industrialists, and artists whose purpose was to finance and advise on collections of textiles, wallcoverings, prints, and drawings, and decorative objects and furniture for the museum. Members gave large sums yearly to the sisters for purchases during their European travels. Eleanor called Hearn “Santa Claus.” The Council functioned generously until 1927 and grew to fifty members, including businessmen and bankers J. P. Morgan and Jacob Schiff and artist and designer Louis C. Tiffany.

Fig. 4 Photograph, Students Studying Textiles, Cooper Union Museum for the Arts of Decoration, reproduction. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. s-e-3456.

Newly acquired collections rapidly established the young museum as a “working laboratory” of arts and design. In keeping with its mission, the museum remained modern in usage; there were few restrictions placed on the use of objects. Collections could be handled, measured, photographed, and sketched. The extensive library was available to broaden the visitor’s education, and the scrapbooks, which in 1919 numbered over one thousand, were full of categorized imagery and known for their “practical instructive value” (Fig. 3-5).

Once the museum was open, Sarah and Eleanor continued to expand the collection by acquiring important European collections. In 1901, they learned that Giovanni Piancastelli, the curator of the Borghese Gallery in Rome, wanted to sell his personal collection of ornament design sketchbooks by Italian artists. The sisters pursued this unique and valuable collection and surmounted all obstacles to obtain the first significant collection of design drawings to enter an American museum collection. The museum acquired 3,620 drawings from Piancastelli in 1901 and an additional 8,226 drawings from his collection in 1931.

Fig. 5 Photograph, Scrapbooks in Cases, Cooper Union Museum for the Arts of Decoration, reproduction from cellulose nitrate negative. Collection of the Museum of the City of New York, X2010.7.5793. s-e-3451.

In 1902, more than one thousand rare textiles from the thirteenth to eighteenth centuries were given to the museum by industrialist and philanthropist J. P. Morgan. The gift was prompted by an inquiry from Morgan to Abram Hewitt about what his daughters were interested in. Weeks later, Morgan cabled, “Have purchased the Badía Collection of Barcelona, also the Vivès collection of Madrid, and the Stanislas Baron Collection of Paris. I do this to give your daughters pleasure.” With this gift, the young Cooper Union Museum possessed one of the top collections of textiles in the world.

Fig. 6 Drawing, Candelabra, ca. 1755 graphite on paper. Museum purchase through gift of various donors. 1901-39-725

When retired architect and decorator Leon Décloux met the Hewitt sisters shortly before 1908, he was not only charmed by them but captivated by the museum’s practical plan of making models and objects accessible. He invited them to his villa for a lunch which led to the museum’s acquisition of a superb collection of rare seventeenth and eighteenth-century French ornamental drawings, decorative objects, and books on ornament and decorative architecture (Fig. 6-9).

Fig. 7 Fragment (Egypt), 4th–5th century warp; s-spun linen. wefts; s-spun linen. s-spun wools. Gift of John Pierpont Morgan. 1902-1-34

In 1913, Sarah and Eleanor were thrilled to be able to purchase ninety ornamental birdcages from the collection of Alexander Wilson Drake. The original architecture of birdcages continues to enchant and inspire students and visitors to the collection.

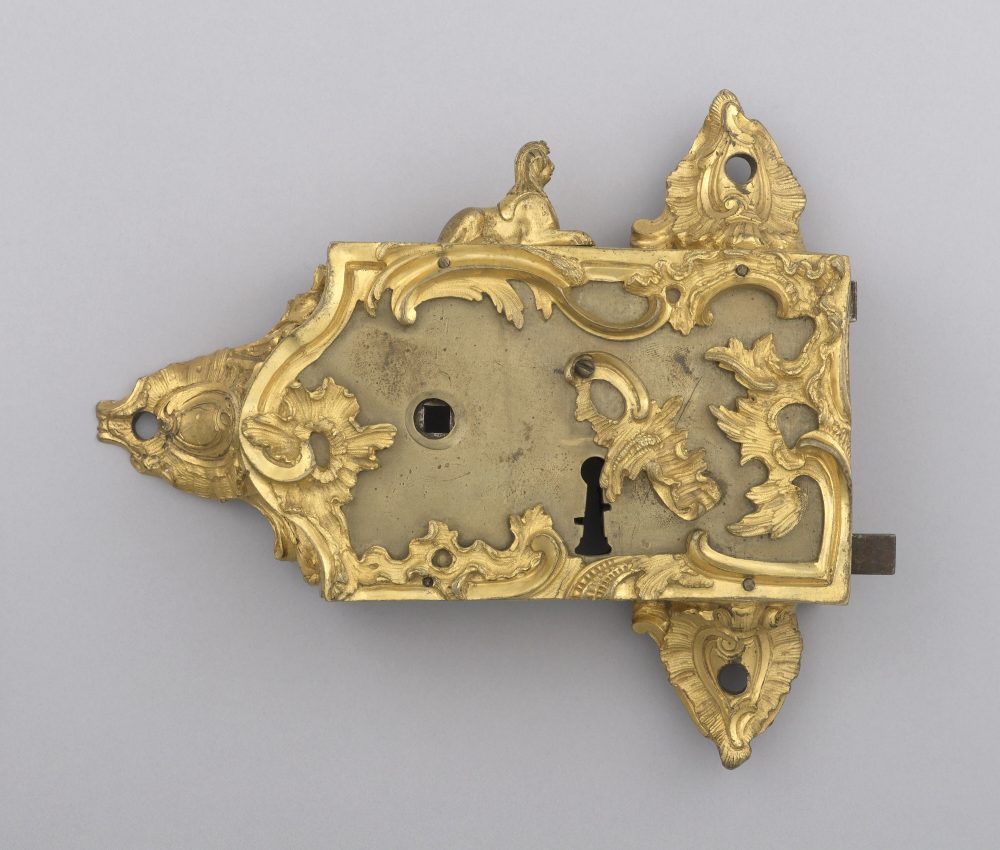

Fig. 8 Box Lock (France), ca. 1745; Bronze, gold; Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum; Purchased for the Museum by the Advisory Council, 1909-25-13-a; Photo by Matt Flynn © Smithsonian Institution

From 1912-1917, personal connections and family generosity led to donations of American works of art to the Museum by Winslow Homer, Frederick Church, and Thomas Moran for the benefit of Cooper Union’s Women’s Art School. Homer’s work was donated by his brother, Charles Savage Homer; Church’s by his son, Louis Church; and Moran’s by the artist himself. Thus, a major collection of watercolors, drawings, and sketches at the museum was established by these noted artists (Fig. 10).

Yearly gifts from the sisters’ wealthy philanthropist friends, including Susan Dwight Bliss, Edith Malvina Wetmore, Elizabeth d’Hauteville Kean, Elsie de Wolfe, and others, added to the museum collections. In addition, Sarah and Eleanor’s many purchases abroad of Spanish tiles, exquisite buttons, illustrated volumes, and embroidered waistcoats—all “documents” of design—further enriched The Cooper Union Museum for the Arts of Decoration.

Fig. 9 Birdcage in the Form of the Rialto Bridge, late 19th–early 20th Century, painted wood, bent metal wire, metal. Gift of Eleanor and Sarah Hewitt. 1916-19-14.

When Sarah died in 1930, The Cooper Union Museum collection numbered 50,444 objects comprised of textiles, wallcoverings, drawings, prints, and decorative objects and furniture. In 1967, with a collection of over 131,000 objects, the Cooper Union Museum for the Arts of Decoration ceased operation for financial reasons. Fortunately, the Smithsonian Institution acquired the collection and established the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Museum of Design in the Carnegie Mansion in New York City, opening its doors to the public in 1976. “Wonders produce wonders,” wrote Eleanor in 1919, “when everything is a miracle, no one step appears unusual.” The enterprising vision of Sarah and Eleanor Hewitt lives on. Today, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum’s collection numbers over 215,000, building on the sisters’ work while embracing ever more diverse examples of contemporary design and the digital world of the twenty-first century.

Fig. 10 Painting, The Yellow Jacket; Winslow Homer (American, 1836–1910); USA; brush and oil paint on canvas ; 57.9 × 39.7 cm (22 13/16 × 15 5/8 in.); Gift of Charles Savage Homer, Jr.; 1917-14-4.

Twelve years ago, Margery Masinter began researching the fascinating history of Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. She was soon joined by Sue Shutte, Director of Ringwood Manor, and Matthew Kennedy. They created the blog series, Meet the Hewitts, which was later joined by the series Short Stories, written by Cooper Hewitt curators and researchers about the collections. In 2022, Cooper Hewitt presented the exhibition Sarah & Eleanor Hewitt: Designing a Modern Museum with project coordination by Matthew Kennedy and concept and research contributions by Margery Masinter. The exhibition was honored by the Victorian Society of New York as the best exhibition of 2022.

A version of this essay was originally written for Cooper Hewitt Membership.

Margery F. Masinter graduated from the Cooper Hewitt/Parsons School of Design MA program in 1993. After graduation she was a special projects volunteer for both the Cooper Hewitt Design Library and the Museum. She has also been a charter Trustee of the Smithsonian Libraries Board and a Trustee of the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum from 2014 to 2022.

Matthew J. Kennedy is the Publications Associate at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, supporting the museum’s publications, exhibitions, and digital content. He received an MA in decorative arts and design history in 2013 from Parsons School of Design and Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. A writer and historian, he specializes in design and theater history.

NOTES

- Cooper Hewitt Short Stories (blog). Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. https://www.cooperhewitt.org/category/short-stories/.

- The Collection. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. https://collection.cooperhewitt.org.

- Eleanor G. Hewitt, The Making of a Modern Museum. New York: Wednesday Afternoon Club, 1919.

- Meet the Hewitts (blog). Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. https://www.cooperhewitt.org/category/meet-the-hewitts/.