Issue 5 2021 Short Essays

Diaspora and Tatreez: Reflections in Stitch

Chelsie Y. Güner

Tatreez, or al-tatreez, is an intricate form of Palestinian cross-stitch embroidery. It is distinguished by rich colors and textures and the technique is typically passed down from mother to daughter, who would begin learning it as early as age six.1 The inherited patterns and colors are often used to identify where either or both the wearer and maker are from.2 Integral to this unique and delicate craft is the understanding that tatreez represents the identity of Palestine and its people. Here, Levantine motifs are understood as functions of matrilineal Palestinian cultural heritage, while also reflecting trade routes and textile and dye developments.3 Tatreez, therefore, functions as a tactile legacy, a folk artistry attributed to women that perpetuates the customs of a region in which political uncertainty, geographic shift, diaspora, emigration, and religious implications are interwoven.4 Tatreez is the materialization of the search for and actualization of collective survival: narrative and intergenerational connection through tatreez becomes a bridge to nationhood and cultural purpose.

The traditional patterns used in tatreez—which are decidedly geometric in shape—also include impressions of daily surroundings indicative of a maker’s geographic location.5 While only one kind of stitch is used, the varied color combinations and motifs come from the natural world. Regional varieties of tatreez can include representations of trees and flowers (the cypress tree, tall palms, apple tree), fruits and vegetables, or animals (mostly birds).6 Varietal iterations of moons and eyes are some of the most immediately recognizable, with most patterns symbolizing prosperity, health, wealth, and protection.7

Groups of geometric designs were given monikers, some quite humorous: “old man’s teeth,” “four soaps in a dish,” and “the baker’s wife,” to name a few.8 Important to note is that Palestinian embroidery does not include patterning or representations of religious affiliation; at least, there are no evident symbols of Islamic representation. Aniconism prevents idolatry in keeping with Islamic cultural conventions and permeates artistic traditions across media by favoring abstract design. Instead, consistent across examples of Palestinian tatreez is a willingness to express some semblance of an individual’s identity within a community, the relaying of one’s connection to homeland and ancestors. Integral here are the stories that accompany each design, communicating personhood as related to community membership, significantly, through the lens of female connection.9 This community-building specifically relates to nationhood; it acts as an extension of personal identity embodied in a shared communal practice.

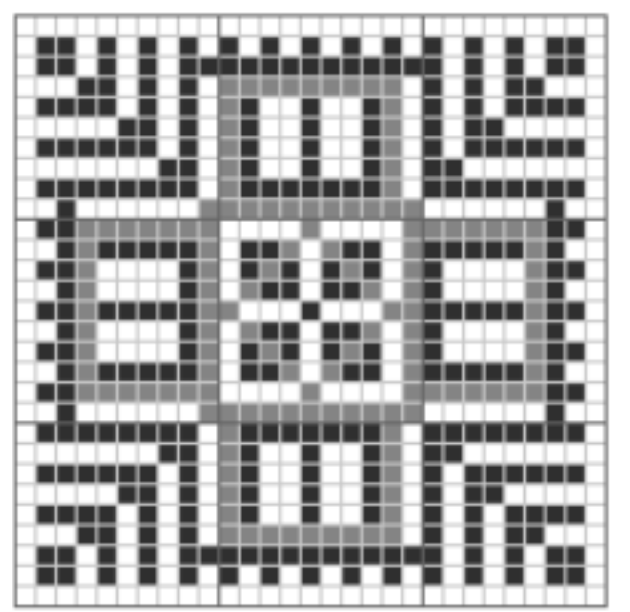

Fig. 1 Front, Dress, 19th century; cotton and silk; Gift of John C. Monks; 1966-93-3. Collection of the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum.

Fig. 2 Back, Dress, 19th century; cotton and silk; Gift of John C. Monks; 1966-93-3. Collection of the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum.

For example, in a modest, full-length, and long-sleeved dress in Cooper Hewitt’s collection (Figs. 1 and 2), dated to the nineteenth century, we likely would find a bride, expectant mother, or elderly married woman.10 Decoding the symbols on the dress begins with identifying two of the most notable and repeated markings across the garment, which are the cross-like symbols on the chest, also strewn down the front, back, and sleeves, as well as the heavily embroidered chest plate, littered with interlinked diamond shapes fitted together to form a large multicolored panel. The cross-like symbol appears to be a variation of a standard moon-with-feathers motif (Fig. 3), though decidedly less intricate than other examples.11 The sleeves are heavily embroidered with alternations of that motif with additional small, decorative leaf-like stitches distributed throughout. It is noteworthy how the patterning moves across the black cotton, with the shoulder decoration leading seamlessly into the ornamentation running down the arms. Here, the simple patterning is made intricate by the alternating colors and geometric motifs that make up most of the stitching. This moon-with-feathers ornament continues down the front of the dress, linked by a colorful line of carnation symbols and is repeated on the back in varying sizes and colors.12

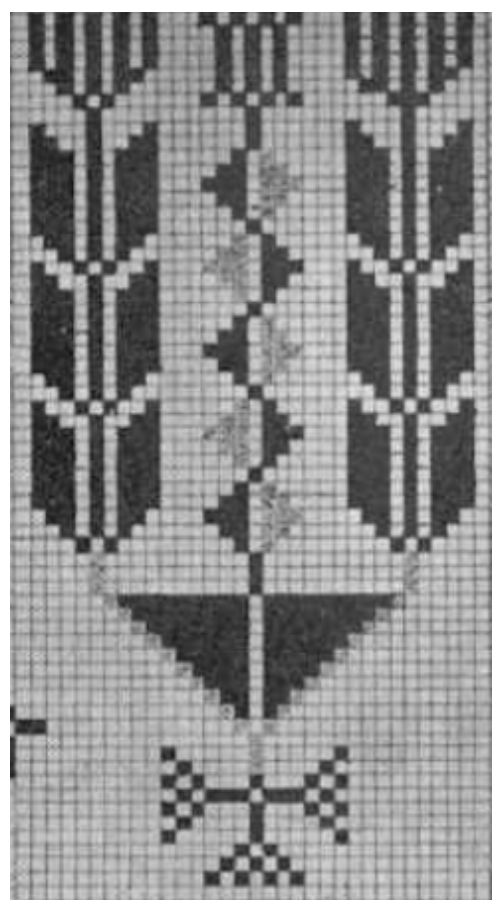

Fig. 3“Moon with Feathers” Margaret Anne Deppe, “An Exploration of Mameluk Close Worked Herringbone Embroidery as the Historical Foundation of Early Twentieth Century Fellahi Cross Stitch Embroidery” (MS diss., The University of Minnesota, 2005), 51.

Moving to the chest panel on the front of the garment, there are heavily embroidered diamond shapes of alternating colors, all with red stitching around them. A key element of the geometric design, the stitching creates an external boundary around the diamonds that echo the larger collection of like shapes on the chest panel. These diamonds appear to refer to a pattern of repeated shapes called “Eastern One,” perhaps indicative of this garment’s origins, its maker and/or wearer’s village, town, or city.13 Notable in this area are variations on the saw and zigzag patterns as well as ears of corn in varying sizes and trails of wheat that adorn the basket-like motifs on the torso of the dress.14

Fig. 4 “Kohl Bottle” Christina H. Jones, The Ramallah Handicraft Co-Operative. (Ramallah: The Ramallah Handicraft Co-Operative, 1962).

These basket-like motifs prove more difficult to decode. They are either a conglomeration of various shapes and forms each with their own distinct set of meanings, or a composite of them, perhaps a variation on the known “Kohl Bottle” form (Fig. 4). This collection of stitches is highly detailed. Important to mention are the notes of magic and superstition that are sometimes represented in tatreez; perhaps what is depicted here is, in fact, an amulet or bejab, which notably takes many varied shapes and sizes.15 There can be varieties of the same symbol. “Saw,” for example, is articulated either in simple, plain repeated triangles—large or small—or embellished by additional stitched dots and markings.

What is clear in this portion of the dress, besides the inclination toward repeated patterns, is a liberal use of red silk in the embroidery process. While distinctly split into two sides by the closure at the front, the shape of the embroidered diamond forms on the bodice are relatively consistent on either side even if the color of the decorative silk is not. For example, the small diamonds at bust-level are geometrically the same shape, but where one diamond is purple and white on the left, its corresponding diamond on the right may be green and yellow, or some other variant color combination. Despite this, all diamonds have ample red stitching around and inside them. Red is certainly the dominant color across the dress. Despite this unifying element, however, significant variations between the left and right side of the dress’s decoration abound—in some moments the stitching is precise and tight while in others it appears hurried or inexperienced. In this, the handmade quality of the garment is evident and revelatory of tatreez as a practice taught to young girls. The notion that some element of learning and artistic growth exists within the dress is made clear in these inconsistencies. These evident moments of teaching and instruction reveal the humanity of the practice of tatreez as parallel to the inclination of the makers to identify themselves, their community, and the natural world around them.

Tatreez as a practice is a form of collective memory, bound in minute stitching and distinct symbolism. This dress sits within a larger narrative space, reflecting cultural heritage through matrilineal folk-art practice, where tactile skill becomes both a safeguard of memory and a collective experience. Here, iconography, female communal practice, and the preservation of cultural and geographic identity meet, testifying to the splendor of the handcrafted. Embroidery becomes an allegorical language of symbols indicative of the power of material culture. As expressions of one’s personal, familial, and communal identity traditionally foreign to the Western world, tatreez invites new scholarship on embroidered textiles as design praxis.

is a student in the History of Design and Curatorial Studies MA program offered jointly by Parsons School of Design and Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. She is a full-time staff member working in International Admissions at Parsons.

Notes

- Shelagh Weir and Serene Shahid, Palestinian Embroidery. London: British Museum Press, 1988 is a strong starting point for a basic understanding of tatreez, as well as full-color pattern charts and photographs. See too Lannom, Gloria W. “Messages in Thread: Palestinian Embroidery.” Faces: People, Places, and Cultures 19, no. 9 (May 2003): 1 as a further simplified starting point for a basic understanding of tatreez. Note that while instruction in this tradition is most often begun at the age of six, it is a practice to be inherited across a Palestinian woman’s lifetime.

- Weir and Shahid, Palestinian Embroidery, 8.

- For details on fibers and dyes, including narrative glimpses of textile trade and development in the region, see Weir, Shelagh. Palestinian Costume. Northampton, Massachusetts: Interlink Books, 2009.

- Though not within the specific scope of this catalog entry, see Tessler, Mark. A History of the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 2009 for further reading on the politics of this regional conflict. For a perspective more closely linked to the contents of this catalog entry, Sharoni, Simona. Gender and the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict: The Politics of Women’s Resistance. Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press, 1995.

- Jones, Christina H. The Ramallah Handicraft Co-Operative. Ramallah, Jordan: The Ramallah Handicraft Co-Operative, 1962 is an exciting report in booklet from the Ramallah Handicraft Co-Operative, an organization that once employed Palestinian refugees to produce embroidery. Here, reproductions from Hood Crowfoot, Grace Mary, and Phyllis M. Sutton. Ramallah Embroidery. London: Embroiderers’ Guild, 1935 (a copy of which is difficult to find), can be seen. See too Deppe, Margaret Anne. “An Exploration of Mameluk Close Worked Herringbone Embroidery as the Historical Foundation of Early Twentieth Century Fellahi Cross Stitch Embroidery.” MS diss., The University of Minnesota, 2005, specifically the reproductions of Crowfoot and Sutton’s charts, re-rendered in black and white for clarity.

- No discourse on Palestinian tatreez would be complete without making mention of Widad Kawar’s impact on the medium as it exists in its modern form within the practice of both hobbyist and researcher. Kawar, Widad. Threads of Identity: Preserving Palestinian Costume and Heritage. Nicosia, Cyprus: Rimal Publications, 2011 is a key text in the deciphering of tatreez symbols. Kawar opens the book by stating “This book is a record of the 50 years that I have spent researching, collecting and a preserving part of the heritage of Palestine,” marking her as an expert and pioneer widely known for her contributions to traditional Palestinian textile scholarship. Also pivotal in understanding tatreez symbols is Tania Nasir’s interview of Kawar in Kawar, Widad, and Tania Nasir. “The Traditional Palestinian Costume.” Journal of Palestine Studies 10, no. 1 (Autumn 1980): 118-129. Notable too is Kawar’s impact on Shelagh Weir’s research in this field.

- Kawar and Nasir, “The Traditional Palestinian Costume,” 125.

- Skinner, Margarita, and Widad Kawar. Palestinian Embroidery Motifs: A Treasury of Stitches. Nicosia, Cyprus: Rimal Publications and Bishop’s Stratford, United Kingdom: Melisende Publishing, 2010.

- For the most contemporary personal reflections on tatreez as it relates to family and community, see Ghnaim, Wafa. Tatreez & Tea: Embroidery and Storytelling in the Palestinian Diaspora. Washington, D.C.: Wafa Ghnaim, 2018. While more narrative in tone, this text espouses generational tatreez practices through the lens of the author’s family, making it a unique look into one home’s relationship with ancestry and craft. Scholars researching Palestinian embroidery would be remiss to neglect anecdotal narrative as it pertains to the tatreez making process.

- Weir and Shahid, Palestinian Embroidery, 8.

- Skinner and Kawar, Palestinian Embroidery Motifs, 54.

- Crowfoot and Sutton’s charts as interpreted by Deppe. Note here that these helpful charts indicate that the bejab comes in a variety of shapes and sizes.

- Jones, The Ramallah Handicraft Co-Operative 5.

- Kawar and Nasir, “The Traditional Palestinian Costume,” 126.

- Ibid, 128.