Interviews & Reviews Issue 5 2021

Designing Gettysburg for the Twenty-First Century: An Imaginative Process

Erica M. Schaumberg

Gettysburg, Pennsylvania is ingrained in American culture for being a turning point during the American Civil War and the site of Abraham Lincoln’s renowned Gettysburg Address. However, many families and college students call this town home and continue to investigate events that shaped the beloved landscape over the last one hundred and fifty years. The significance of Gettysburg outweighs the number of tourists who visit every year; Gettysburg’s romanticized and somewhat mythic identity at times infringes on the gruesome reality that left an everlasting wound on American culture. I had the opportunity to interview Dr. Shannon Egan and Dr. Peter Carmichael on the topic of Gettysburg and how the idealized narrative of the battle is understood within the current debate on Confederate monuments, and how their programming has responded to recent political tensions around the Black Lives Matter Movement.

Erica Schaumberg: Gettysburg exists on many levels. You can experience Gettysburg through historic buildings, kitschy souvenirs, and re-enactors all within the same block. How does design and material culture interact with Gettysburg as a historic landmark and tourist attraction?

Dr. Peter Carmichael: As soon as the battle ended this place became a site of commercialism. From all across the area people descended to acquire and sell relics. Artists were trying to make money from lithographs, drawings, and photographs right after the battle ended. But the best way to understand the very long history of how Americans have interacted with Gettysburg is to think of it as an imaginative process. The imaginative process is very place and time specific. Shortly after the war the imaginative process had as much to do with the beauty of the landscape of Gettysburg as it had to do with the battle itself. People came to reconnect with the ground well into the late 1800s.

Today, Gettysburg speaks directly to how commercialism always romanticizes or glorifies war. We see that in the process of the reenactment and in all of the things sold in the tourist shops on Steinwehr Avenue. We find things that capture people’s imagination of the past; how they want to see this place in heroic and dramatic terms. We have to recognize especially that for young people it is an opportunity to make an historical connection that often leads to a lifetime of learning. However, there is a dark side to the kitsch that is deeply political and advances the cause of right-wing ideology. One of the T-shirts in the shops I saw for years read, “If I knew all this I would have picked my own damn cotton.” It is disturbing. I think in the last few years, that type of commercial product is not as prevalent as it once was, but there are still other T-shirts and bumper stickers that make it very clear that the Civil War can be used as a way to justify a far-right perspective.

In the town of Gettysburg, like in any historical landscape, most people do not understand that it has changed over time. People do not see the layers of the past. There is nothing in the town that would remind them of these changes. People come to Gettysburg and want to imagine it is a static place frozen in time. As historians we want to be able to guide our visitors when they think they are making that journey into the past, to make them realize that they cannot recover the past as it was. I do not want to ruin the fun of people studying the past. I do not want a historian whispering in their ear…well, it wasn’t like this in 1863 or don’t forget about this story in 1863. People like myself and Shannon want to elevate the thinking of people who come to Gettysburg. We want them to see the landscape more critically.

Practically speaking, most visitors might have one day to spend at Gettysburg at most. It’s blazing hot and the kids are indifferent. You have a limited amount of time as a public historian to make a meaningful connection to Gettysburg for these visitors. That connection depends on the spark of imagination that this place inherently has. Gettysburg is as dangerous as it is evocative and seductive. It is so beautiful. You put the monuments there and it is not surprising that a young mind comes here and sees this as a vast playground where you can imagine going back into time. We have to find ways to change the conversation and be strategic about it, to have people contextualize the war realistically.

ES: How has programming in Schmucker Art Gallery responded to the imaginative process tourists seek?

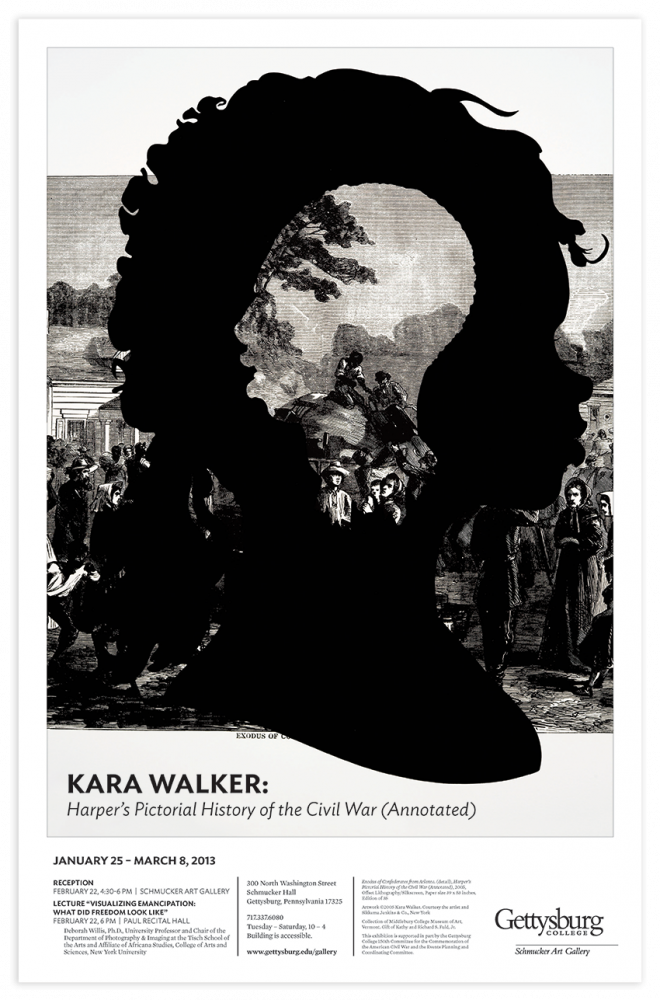

Dr. Shannon Egan: Around the time of the Sesquicentennial of the Civil War, the Gallery responded with programming that would challenge conventional narratives and approaches to the War. We were particularly thrilled to have the opportunity to show Kara Walker’s series Harper’s Pictorial History of the Civil War (Annotated) in 2013. Walker’s prints directly allude to the kitsch and the romance of Gettysburg that Pete describes and invites the viewer to be more critical of how the Civil War has been marketed to tourists. We also had on display the volumes of the original Harper’s Pictorial History of the Civil War, on loan from Musselman Library’s Special Collections. Visitors could see the juxtaposition of the real historical artifact with the artist’s appropriation of this source. As a Black woman artist, Kara Walker offers a voice that is markedly different from many of the tourists who visit the Battlefield. I think Kara Walker has opened the door for other artists to be critical of this American landscape.

Fig. 1 The exhibition poster from Kara Walker: Harper’s Pictorial History of the Civil War (Annotated) in 2013 marked a pivotal change in the way Schmucker Art Gallery curated works by African American artists while responding to Gettysburg’s history. Walker’s appropriation of prints published in Harper’s Pictorial History of the Civil War disrupted Gettysburg’s idealized narrative.

PC: The challenge that faces Kara Walker’s work is a similar problem to what academic historians face. Sometimes our content is not easily accessible to people. For ordinary folks it just doesn’t connect. But there are possible lines of communication that can be built. I think Walker’s work treats themes that matter to public history sites such as Gettysburg. It is a mistake for anyone to say that the experience for the Gettysburg visitor today should be one that is exclusively about the battlefield, tactics, generals, and nothing else. Public historians are not frozen in an antiquated version of history or visual culture theory. Academics need to find a way to make work like Walker’s more accessible; Walker’s work is extremely relevant to the events that happened at Gettysburg. I don’t think visitors are remotely close to recognizing that point yet.

SE: It is important to note that the original lithographs Walker is appropriating were quite popular in their time and that these motifs and subjects are repeated in various ways in pictures and décor found in restaurants and shops around town. Harper’s Pictorial History of the Civil War (Fig. 1) was intended to be accessible. And Walker’s own success as an artist might in fact make her more accessible and familiar to some viewers. For instance, her more recent monumental sculptures in Brooklyn and London have been well-received, but you’re right that her work requires more critical thinking and understanding.

ES: There has been a growing concern over Confederate monuments across the American landscape. Gettysburg’s monuments are part of the National Park and are viewed by thousands of tourists and students every year. Where does Gettysburg exist within the Confederate monument debate?

PC: The Confederate monuments at the National Park cannot be removed until there is congressional legislation. Which of course is a possibility, but right now they are there, and, as an institution, we have an obligation to work with the National Park. We are all committed to contextualizing those monuments as part of a commemorative landscape. Recently at the Civil War Institute we have led public tours at the Virginia Monument. It is an equestrian monument that has Robert E. Lee. It dominates the field. It is a monument that embodies all of the themes of the Lost Cause. We have talked about the installation, the commemorative events surrounding the monument, and more importantly how that monument speaks to visitors today. The intent of these programs is to get people to think historically about these monuments, understand the political debates today surrounding the Confederate flag and these monuments, and ask why these monuments were installed. I think many folks who want to see all Confederate monuments ripped out of their foundation and discarded have come to appreciate the historical meaning they have on a national battlefield site such as Gettysburg. The monuments are central to Gettysburg as an outdoor classroom, and as a public historian I need them to talk about the controversial tensions we are engaged in today.

ES: Can you speak to the relationship among Gettysburg monuments, the organizations that funded them, and the monuments’ designers? How can they be used to discuss the Civil War and race in the United States?

SE: Well, the North Carolina Monument was designed by Gutzon Borglum who is best known for his work on Mount Rushmore and Stone Mountain in Georgia. Borglum was deeply involved in the Ku Klux Klan, attending rallies, joining committees, and dedicating himself to glorifying the Confederacy. He was a white supremacist, yet his work stands triumphantly on Seminary Ridge. In order to provide a different perspective on how war is commemorated and remembered, we’ve had speakers and artists in the gallery discuss other artistic responses to the aftermath of the war, including other conflicts from Hiroshima to wars in the Middle East. I’m proud to have had the opportunity to hear scholars Kirk Savage, Megan Kate Nelson, Deborah Willis, and artists Wafaa Bilal, Susanne Slavick, and elin o’Hara slavick share their work with us over the years. To me, it is so interesting to use Gettysburg as a springboard to thinking about war more broadly and to make interdisciplinary connections among conflicts.

PC: The United Daughters of the Confederacy today has about zero presence on the battlefield, but the forerunner of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, the Ladies Memorial Association, was critical in leading a campaign in the 1870s to disinter the Confederate dead here at Gettysburg and have them reburied in cemeteries across the South. That movement is a reminder of how Gettysburg as a commemorative landscape has been shaped in decisive ways by these women. Their message and agenda has evolved and changed overtime, but the one consistent thread is their message of honoring and remembering the Confederate dead. Every time they make that claim they are insisting that they are never being political, but every time these women commemorated or remembered a piece of Confederate history it was certainly for a political cause.

ES: How has your programming changed due to the Black Lives Matter Movement existing within the Trump era and rise of right-wing extremists?

SE: Providing a platform to examine issues of race and installing the work of Black artists is central to our collections policy and the mission of the gallery. In addition to exhibitions of work by Glenn Ligon in 2014 and Kara Walker in 2013, we installed Art, Artifact, Archive: African-American Experiences in the 19th Century and Identities: African-American Art from the Petrucci Family Foundation Collection in 2015. Students enrolled in my Art and Public Policy course wrote essays for both exhibition catalogs concurrently, and I think they did a fantastic job with challenging material. More recently, we have acquired works by Black artists Carrie Mae Weems, Zoë Charlton, James VanDerZee, John Biggers, James Lesesne Wells, and Martin Puryear, among others. Their works offer opportunities to tell more stories about African-American culture and history, and many offer new ways to understand the significance of these experiences in relation to the battlefield.

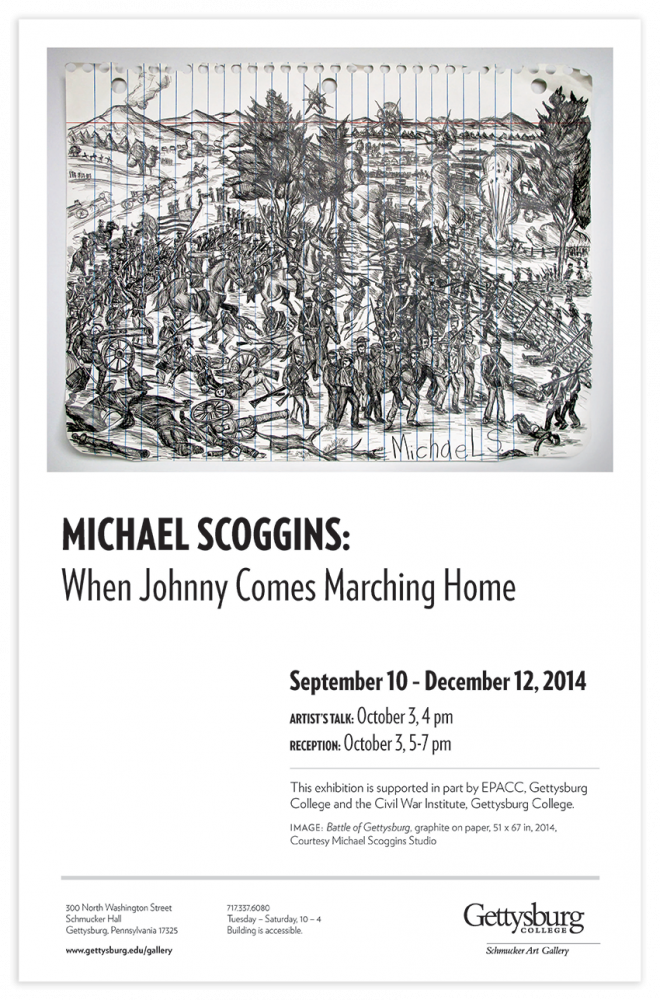

Fig. 2 The exhibition Michael Scoggins: When Johnny Comes Marching Home exhibited large scale works by the New York based artist in 2014. This poster features “Battle of Gettysburg” which juxtaposes Gettysburg’s historical legacy with Scoggins’ childhood references. The exhibition confronted popular culture’s influence on historic locations such as Gettysburg.

Prompted by the 2014 exhibition, Michael Scoggins: When Johnny Comes Marching Home (Fig. 2), students discussed the artist’s critical use of the symbolism of Confederate flags and made connections between contemporary politics and nineteenth century white supremacism. It was the first time students told me that some students hung Confederate flags in their dorm rooms. It would be even more disturbing to hear if this was happening in 2021. It would be someone’s overt declaration of racism. In conjunction with The Plains of Mars: European War Prints, a gallery exhibition in 2018, Pete put the European war prints in context with Civil War battle images. He brought in those paintings from the shops with those very white men fighting for their country. Now you’d look at them and think it is a white supremacist’s fantasy. They are totally sanitized and kitschy.

PC: The value of visual culture and importance of art history is starting to become integrated into what historians do; it is certainly what I do on the battlefield. The work Shannon has done in the gallery through speakers and events are attended by students across all departments. I know history students go to the gallery as part of their class. I know the speakers we work with have opportunities to go onto the battlefield and have the chance to think about themes differently. To have Schmucker Art Gallery right here on the battlefield allows us to make the most of Gettysburg. The collaboration with the art gallery has really given us a platform we did not have before. We can have programs that focus on the experiences of African Americans whether during enslavement, reconstruction, or later. The scholarship on the African American experience is rich. The work that has been done and is being done is crucial. In the last six months we have become more attentive to creating battlefield experiences that focus on issues relating to African Americans and the Civil Rights Movement. I am pleased to see how the field has changed. In 1985 I was working at Appomattox. When I was there the historian instructed us to stress the story of reunion of north and south. The current Gettysburg students we place at Appomattox National Park through our Pohanka Internship Program give talks about the war continuing after the war, how the struggles of emancipation continued. I had one student give a tour specifically at the cemetery of enslaved people. I feel a sense of pride that my students are on the front lines of history, that they are telling these stories. The story of the cemetery of enslaved people is a story I knew of as a kid, but I was unable to talk about it at Appomattox in 1985 because it clashed with the official narrative of the national park. Things have changed dramatically since then, and it’s a good thing.

ES: Gettysburg as a town, historical battlefield, and college continues to evolve in response to changes in American society and politics. The people of Gettysburg will keep telling the location’s stories and Gettysburg will continue to impact our understanding of history and the twenty-first century.

received her MA from Parsons School of Design in 2020 and her BA from Gettysburg College in 2018. Throughout her education at Gettysburg she worked extensively at the Schmucker Art Gallery. Currently, Erica and fellow alum Virginia Pollock are collaborating on an Instagram account and podcast dedicated to making the study of art and design easily accessible, relatable, inclusive, and approachable.