Reviews & Interviews

Can’t Live With It, Can’t Live Without It: The Museum of Broken Relationships

Erik Livingston

FIG. 1 Interior of the Museum of Broken Relationships, Zagreb, Croatia.

While perusing the arts section of the New York Times, I stumbled on a piece which made me do a double take. Entitled “When Relationships Fail, This Museum Keeps the Stuff Left Behind,” this article looks into the Museum of Broken Relationships, based in Zagreb, Croatia.1 The institution defines itself as “a global crowd-sourced project” whose purpose is “treasuring and sharing your heartbreak stories and symbolic possessions.”2 Portions of the collection are available online, where they are displayed along with an image and a description from the donor regarding the object’s former significance.

Identification and, consequently, disidentification with objects is at the heart of this museum. Think of your relationships: not only romantic but platonic, professional, and familial. We attach meaning to seemingly random things because they communicate memories and sensations to us. Here is an example from my life: I had a friendship that ended in flames when I was in high school. The friend had given me a pin of Van Gogh’s Skull of a Skeleton with Burning Cigarette (1885-86) before we parted ways. I used to put it on my jacket every day, wearing it for about three years. I truly loved that pin because it had become a totem of a relationship I treasured, not to mention I just enjoyed it aesthetically. But, when that chapter of my life ended, I slowly stopped wearing the pin, quietly putting it in a drawer and trying never to think about it. It no longer carried its former weight and became like a stranger to me, or a phantom limb whose lingering mental cicatrices no longer hurt, yet the memory of its ability to do so and its nostalgia-inducing qualities persisted. The pin stayed far from sight until I found it when preparing for a garage sale. Objects like this represent a nostalgic “sentiment of loss and displacement…but…also a romance with one’s own fantasy.”3 The pin was always just a pin. The only meaning it carried was what I superimposed onto it. The pin itself did not make me sad for a lost friendship: it was the persisting memories of a romanticized past, which I enabled the pin to represent.

These types of objects populate the museum-things we cannot bear to have in our lives but whose power remains in a liminal state, vacillating between potencies. Yet, despite this, we cannot take the final step to throw them out or destroy them. Such objects become ruins, within which the “past is both present in its residues and yet no longer accessible.”4 Nostalgia is triggered by these cherished and despised mementos, where all our memories and experiences, lived and imagined, converge to form personal ghost towns. We see the traces of life, hints, and glimmers of past enjoyment and scorn, fusing into melancholic specters. In trying to combat nostalgic ghosts personified by our things, we give them away for free, perhaps as the ultimate fulfillment of a silent hope that a once treasured object will take on another meaning, this time only far away from us.

Many of the donated items within the Museum of Broken Relationships speak to these complex emotions. An espresso machine donated from Paris, France lists the relationship duration as “too long, last 20 years of the past century.” The donor recounts how they would make their partner coffee every day, but,

then, one day, he no longer loved the coffee I made for him using the espresso machine he gave me. And then, one day, he no longer loved me and left. And so I took the espresso machine he gave me that made the coffee he loved and I put it in the basement so I don’t have to look at it anymore…But every time I come down to the basement, there it is.5

The donor of another item, a sign made of license plates that spells “Wubbs” (the pet name for a couple’s cat), laments,

I can’t bear to look at it anymore. I can’t donate it because it’s so personal to our story. I also…can’t seem to throw it away. It evokes feelings of happiness…on the other hand, it makes me sad and angry…I’d be happy to donate the sign to the museum. This way the special memory won’t die the way our marriage did.6

Even in our pain, we cannot bear to part with the objects we have inscribed our lives and personal histories onto. This is where the Museum of Broken Relationships comes in.

Looking at the digitized collection, most of the objects would not surprise us. There are Claddagh rings, drawings, watches, and tchotchkes. Some artifacts make us raise our eyebrows, like an ax, fluffy pink handcuffs, and a dildo. Others, however, inspire an emotion that sits at the intersection of disgust, bewilderment, and amazement. These include a gingerbread cookie, belly button lint, dreadlocks, and a “Twenty-seven-year Old Crust from a Wound of my First Love.”7 In many critical ways, this museum expands definitions of material culture. When someone preciously saves their partner’s belly button lint, or a scab, or hair, that piece of biological waste becomes objectified. We, ourselves, are objects. In the memory of those we love and hate, in the things we leave behind. This museum objectifies the human body, but honestly, I am not against it.

When I was an undergraduate, I worked in my college’s archives. Our main purpose was to preserve the history of the school, its students, staff, and faculty. We frequently received donations of ephemera that did not fit the purpose of our collection, thus requiring us to decline them. Many times, the donors would not want the materials back, viewing the archive as a more socially ethical alternative to a paper shredder. My supervisor and I had many conversations about the unique weight we felt when we had to discard materials and the powerful position an archivist, or any collection steward, is placed into. She shared with me an old photograph of an unidentified woman that, for some unknown reason, she felt compelled to save from the trash. While there, I had many experiences like this myself. Once, I found an old to-do list sandwiched between donated magazines. It was destined for the garbage, but, for whatever reason, seeing this handwritten list on faded paper that only said “1. get wine. 2. do homework. 3. get dinner. 4. see David,” filled me with such a sense of affinity and attachment that I pocketed it, unable to throw it out. When I returned to my dorm, I found it had fallen out of my jacket when I grabbed my keys. I felt a nauseating sense of nostalgia which did not belong to me but the list’s former owner. I quietly mourned the piece of paper, then got in my car and pretended I was not affected by the loss of this stranger’s trash treasure.

Scraps and ephemera haunt me. Things that do not have any social or monetary significance, such as small pieces of paper, photographs, or knick-knacks, but still consume a portion of our minds. When I glance around my room, half of what I have plastered on my walls is trash I recontextualized. Movie ticket stubs that do not belong to me, photographs of people I do not know, magazine clippings, postcards, and my undergrad’s 1976 Commencement program. The discarded objects of our affection, no matter how much we try to disassociate from them, maintain an aura which perpetually recalls its “presence in time and space, its unique existence at the place where it happens to be,” carrying the ability to induce nostalgia that does not belong to us.8 Even those things we do not have an immediate connection to, like the litter I have collected, still inspire within us a range of feelings, as if we are witnessing the purest, microcosmic view of a life we will never know. I am horrified by the idea that one day, when I am dust, the objects I have transformed into quasi-holy personal relics, even the ones I will grow to disavow, will be so dissociated from the memories I attached to them that whoever stumbles upon them next will only think of them as junk.

FIG. 2 Objects on display at the Museum of Broken Relationships, Zagreb, Croatia.

Now. Returning to the Museum of Broken Relationships. My existential musings have most likely imparted why I feel this collection is so significant. But, if not, I will elaborate further. We all recognize the importance, both positive and negative, of museums. They, in theory, act as repositories of global human experience and have the potential to function as sites for community, education, and research. But at what point is this not enough? How in the world can we preserve the ugly human side of humanity? What do we do with the non-artistic, non-archival trash that means nothing to others but everything to us? Truly, I think I have gleaned more about modern European society from an ax a man used to destroy the furniture his ex-girlfriend left behind than I have from Le Corbusier.

At the end of the day, the Museum of Broken Relationships is an institution dedicated to emotion. It strongly forgoes the typical stoic impartiality of contemporary museums in favor of the unfiltered and raw display of the human experience. The museum provides a unique opportunity to challenge the very idea of what a collection should be and how curators should approach it. Here, everything is crowd-sourced. An object’s catalog description contains the location where the relationship occurred and its duration. Accompanying this is a paragraph or two from the donor. Often these tell us how the object mattered to them, sometimes not. Without these stories, most of us would see these things as garbage. But with them, they are energized, becoming objects of admiration, hatred, derision, and nostalgia. The Museum of Broken Relationships repositions un-glamourous scraps as historical evidence of human emotion. The weight of memory makes them invaluable.

I keep returning to this one artifact in the collection, a postcard donated by a 70-year-old woman from Yerevan, Armenia. The postcard is a photograph of a man and a woman sitting in the grass, looking at each other and smiling. The blue sky behind them and the woman’s red dress are the only things in color, appearing to have been added by hand with a marker. At the bottom, handwritten in Russian, reads “pomni tot dyen’ nashyey progoolki i nye zabivai (sic),” “remember the day of our walk and don’t forget.”9 The donor explains that a long time ago, this postcard was slipped under her family’s apartment door by the son of their neighbor, who had fallen in love with her. She goes on, recounting that “following the old Armenian tradition, his parents came to our home to ask for my hand. My parents refused saying that their son did not deserve me. They left angry and very disappointed. The same evening their son drove his car off a cliff…”10

To think this might have been thrown out after she died by an unknowing family, to think we might have lost a hyper-localized history that speaks to far-reaching geo-cultural issues. To think we could not immortalize humanity is beyond me. While attaching oral histories to all museum artifacts may seem impossible, I believe this approach can be adopted by smaller institutions and archives with strong community ties. We are still grappling with colonial notions about museums, delusions of them being hallowed buildings akin to places of worship. I believe it is time to forgo the sanctity of the museum and embrace the humanity of objects and people. Approaching such institutions with a more anarchist, community-driven perspective enables us to radically transform the position of the museum in contemporary society. The lives of objects, and the memory and nostalgia they induce, are what makes them matter, and this is precisely what the Museum of Broken Relationships has figured out.

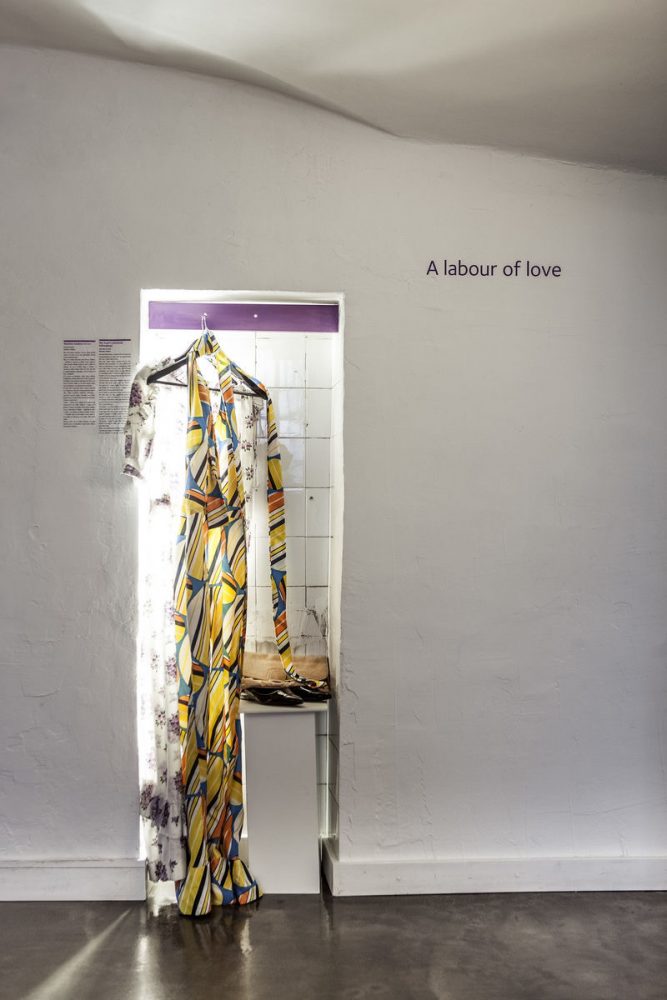

FIG. 3 A donated piece of clothing on display at the museum, Zagreb, Croatia. Courtesy of the Museum of Broken Relationships.

Erik Livingston (he/him) is an MA student in the History of Design and Curatorial Studies program offered jointly by Parsons School of Design and Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. He joined the program after graduating with a BA in Art History from the College of Wooster, where his undergraduate thesis interrogated the intersection of postcolonialism, memory, and nostalgia in Russia following the collapse of the Soviet Union. His academic interests include the international avant-garde of the 1910s-1920s; the history of the book; print culture; book bindings; the history of photography; 19th and 20th century American art, design, and material culture; colonial and postcolonial studies; memory; and nostalgia.

NOTES

- Alex Marshall, “When Relationships Fail, This Museum Keeps the Stuff Left Behind,” The New York Times, February 14, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/02/14/arts/design/museum-of-broken-relationships.html.

- “Explore the Museum,” Museum of Broken Relationships, accessed February 15, 2023, https://brokenships.com/explore.

- Svetlana Boym, The Future of Nostalgia (New York: Basic Books, 2001): xiii.

- Andreas Huyssen, “Nostalgia for Ruins,” Grey Room, no. 23 (2006): 7.

- “Espresso machine,” Collection, Museum of Broken Relationships, accessed March 1, 2023, https://brokenships.com/explore/espresso-machine.

- “Sign made of license plates,” Collection, Museum of Broken Relationships, accessed February 28, 2023, https://brokenships.com/explore/sign-made-of-license-plates.

- “Twenty-seven-year Old Crust from a Wound of My First Love,” Collection, Museum of Broken Relationships, March 1, 2023, https://brokenships.com/explore/twenty-seven-year-old-crust-from-a-wound-of-my-first-love.

- Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” in Illuminations: Essays and Reflections, ed. Hannah Arendt, trans. Harry Zohn (New York: Schocken Books, 1969): 168.

- “A postcard,” Collection, Museum of Broken Relationships, accessed March 1, 2023, https://brokenships.com/explore/a-postcard.

- Museum of Broken Relationships, “A postcard.”