Interviews & Reviews Issue 5 2021

But is it Theater?

Matthew Kennedy

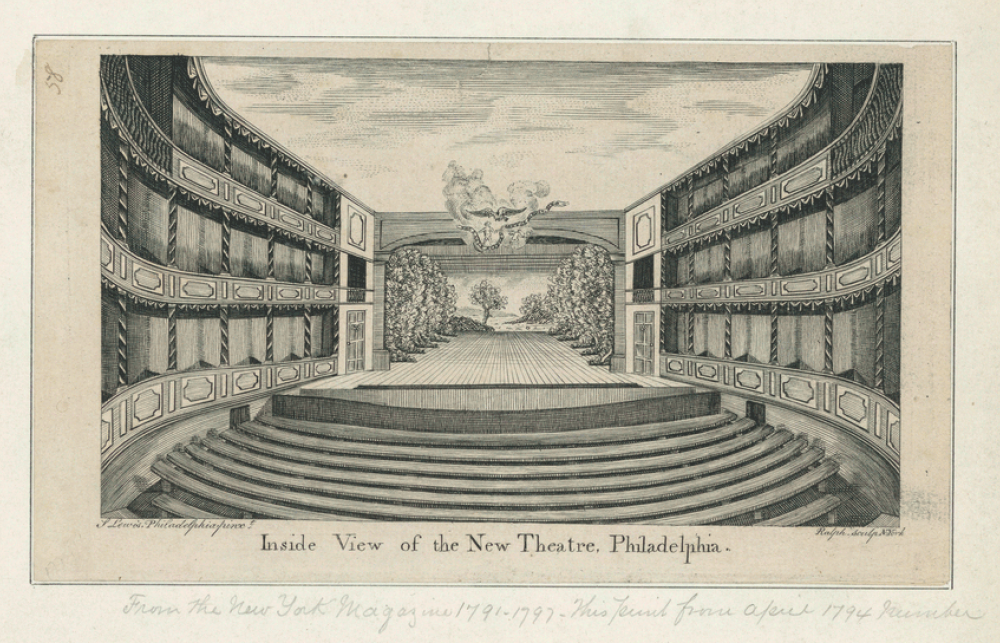

Print, Interior View, New Theater, Philadelphia, 1794; Designed by W. Ralph (active 1794–1808); engraving on paper; H x W: 11.4 × 19.4 cm (4 1/2 × 7 5/8 in.) Mat: 35.6 × 45.7 cm (14 × 18 in.); 1948-89-1. Courtesy of Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum.

But is it theater? This question bobbed around the internet in 2020 as live performances around the world were suspended due to COVID-19 and all forms of media quickly coalesced to be “streamed” online. Readings of plays and musical concerts from performers’ apartments filled the void of in-person performance, while also raising existential questions of what constitutes live performance.

What makes a streamed play “theater” when one is not in a theater? The performance history of the text? The résumés of the actors? The intention of the author? How the production is marketed? Neither theater nor television nor film, perhaps internet-based experiences lack a nuanced vocabulary beyond being labeled “stream”? Mainstream theater in general has a conflicted relationship with the internet, as any act of recording, particularly to convey online, infringes on the arguably sacred quality of the in-person performance. But agility and innovations in the past year demand broader thinking about the traditional artform of theater—even if the question is largely academic with a (hopefully) fast-approaching expiration date as we start to eye a post-pandemic world.

Streaming, conferencing, and social media platforms are designed interfaces and experiences often meant to be relatively unobtrusive, with slim, slick interfaces. Some honor the power of their brand, overlaying content with graphics and filters. Whatever the approach, there are limitations to the medium. There is the inescapable flatness and a near-complete inability to create any sense of scale. There’s also the revelation that good lighting and a sturdy internet connection are commodities that even the biggest names in the business cannot buy. Designers severely lack control of how the performance will be seen. Many productions modestly attempted some form of visual cohesion, such as actors dressing uniformly or sitting against a white wall. But in the midst of this muted/unmuted, having-trouble-connecting world of technologically arbitrated live interaction, two streamed plays—Heroes of the Fourth Turning and Circle Jerk—embraced or defied the stream-constraints placed by 2020. Both shows used the medium of streaming to intensify the drama, or even to create it.

*

On a brisk weekend in October 2020, a chilling drama set in rural Wyoming took place in five performances over Zoom. This play, Heroes of the Fourth Turning by Will Arbery, performed seven months into theatrical isolation, is a rumination on fear of the future, that unexpectedly echoed the lonely, divided connotations of the Zoom medium. The play ran at Playwright’s Horizons in New York City in fall 2019, after which it was a finalist for the 2020 Pulitzer Prize for Drama. In Heroes, four alumni of a conservative Christian college reconvene near the school after a party honoring the appointment of a new college president. Teresa is argumentative and a firebrand of conservative talking points. Kevin is drunk and laments not having a girlfriend. Justin is quiet and closing himself off from the rest of the world in this rural town. Emily, who has recently returned from some time in Chicago working at a women’s health clinic, is recovering from an unidentified illness that has left movement difficult and she is largely confined to her chair. Throughout their discussion—each in their own Zoom frame—they circle one central question: what can conservatives do in a world they perceive to be increasingly conquered by liberals? Focusing on these politics, their discussion reveals a multi-perspectival ideology and a possible way forward for them, forming an uneasy matrix of empathy, coexistence, monastic avoidance, and violence, if necessary. (Taking place deliberately in 2017, the characters are certainly aware of the forty-fifth Presidential administration, but they cannot address its full dramatic arc.) As the performance bears on, each character settles into their Zoom cell, seemingly becoming an archetype within the conservative fold. While such a circumstantial drama is far from an innovative structure, the discourse presented—the hopes and fears of young Christian conservatives—is one rarely examined in contemporary American theater.

Heroes is fiercely intellectual, projecting stirring words, ideas, and passions that go beyond the need for any heavy-handed design interventions. And in this streamed production, the design interventions were minimal: each performer’s backdrop was stark and black, and, perhaps most impactfully, they were lit with overhead, confrontational lighting. This simple approach unified each performer’s isolated space, but through a coordinated, consistent aesthetic that echoed the mood of the play itself. While the design was minimal and uncomplicated, it was undeniably thoughtful to profound visual and psychological effect. The dark background additionally mimicked the original scenic design of the stage production, by Laura Jellinek, which featured a modest rural residence with an ample lawn set before a stark black background. While the events of the play take place at night, the black background surrealistically infuses and divorces the space from any realistic sense of place. As staged in such a vacuum, the darkness emphasized the characters’ isolation, abstracting their detachment.

Ultimately, the production transcended the mundane quality of video conferencing by exploiting its inherent flatness and separation to reinforce isolation, claustrophobia, and uncertainty. This uncertainty radiates throughout this elusive play, the characters and their politics, echoing a tenuous moment in American politics at large.

*

In Circle Jerk, it is winter on the fictitious locale of Gayman Island, and there is a crisis on the internet. Two right-wing gay men, Jurgen and Lord Baby Bussy, rich from success in tech, have been cancelled online for their white gay supremacist sentiments and decide to create a BIPOC female deepfake (a digitally manipulated image in which an individual’s likeness is imposed on the existing image of another person) in order to reclaim control of the internet. Circle Jerk is a calamitous, sometimes convoluted comedy that is an indelible child of the internet and challenges the question “Is it theater?”

Developed by Fake Friends, a Brooklyn-based theater and media company composed of writers, actors, and dramaturgs, the play embraces the theatrical invasion of the internet, employing theatrical expertise for structure while pillaging cyber space for content and satire. According to Fake Friends, “Circle Jerk is a queer comedy about white gay supremacy, a homopessimist hybrid of yesterday’s live theater and today’s livestream (set in tomorrow’s news cycle). . . . In an era when truth is dead and fact is fiction, Circle Jerk is a realistic comedy about a bleakly farcical reality.”1 The show reportedly was developed originally to be performed on stage in 2019 at Ars Nova in New York City with a summer run planned for 2020; after viewing the streamed production, with its persistent integration of internet culture and digital-born media, it’s hard to imagine this as anything other than an internet production.

Filmed live in October 2020 (after a cast-and-crew quarantine) for each stream in Theater Mitu’s MITU580 Space in Brooklyn, the set featured approximately three distinct spaces: a living room dressed in a silver and purple palette to convey a cool, gaudy opulence; a tech lair, featuring a desk with a computer monitor surrounded by scaffolding, chains, and equipment; and, appearing in Act III, a space, purely technical, for cameras and ring lights for when the performance devolves into selfies, memes, and social media interventions. The identifiable spaces serve as signifiers of physical place as the action of the play moves, ultimately, to the limitless expanse of cyberspace.

While the main characters deal with their internet crisis, a series of characters are introduced in the living room as if in a sitcom. Act I ends with the generation of the deepfake bot. The character’s computer screen on which the figure is revealed—a hot pink background with a woman in a white wig and exaggerated white eyelashes—fills the viewer’s screen, beginning the merger of the virtual world with the theatrical space. The plot takes a loop in Act II when the woman whose image was manipulated and deployed as the deep fake mysteriously arrives on the island, proclaiming herself a voice for colonized peoples, jeopardizing the cyber plot and the relationships of the friends. By the play’s third act, the plot fractures with an intentional invasion of artifacts of the internet—YouTube clips, memes, GIFs, TikTok videos—making it feel like a fast scroll of a social media timeline rather than a static Zoom call. This bombarding of interfaces and familiar memetic imagery was likely unremarkable to the regular internet user, but the recognition of it was integral to its comic effect. Some referred to it as a “digital theater show”2 for an audience mediated by technology; the third act became so chaotic with shifting video and imagery that it would likely have stumbled and lost momentum if it had to hold for laughs from an in-person audience.

In the words of critic Helen Shaw: “You know how it feels when you lose all your open web tabs and suddenly can’t remember a single article you were reading? It’s a bit like that: too much attention, and too little.”3 This is perhaps the conclusion of Circle Jerk: cleverly theatrical, densely witty, and immensely intriguing while knowingly succumbing to the narrative chaos of the internet. And quickly exited by closing your browser window.

*

These two productions have a common thread in that they are both produced by Jeremy O. Harris. After making a bold Broadway debut writing Slave Play in 2019, Harris has emerged as a provocative voice in American theater. He possesses a cleverness and affability that almost might be annoying if it wasn’t so well executed and his pursuits not so altruistic. Harris produced both of these streamed productions with discretionary funds he received from HBO as well as royalties from his own produced plays. On the decision to produce digital theater during the pandemic, Harris commented, “This is actually a great opportunity for drastic shifts in what we think theater is and how we can make it accessible. People think about accessibility, and they think I’m only talking about Black people or young people, but no, there are literally people who physically can’t be in a theater . . . How do we make it possible for them to see theater all the time?”4 And through his patronage and vision, Harris might be forging—however experimentally—a viable digital theater of the future. But is it theater? Does it really matter? As Harris says, “Obviously, theater is not on its last legs. Theater is this amazing mutating beast that doesn’t hide when things get tough. It can roll with the punches.”5

received his MA from the History of Decorative Arts & Design program offered jointly by Parsons School of Design and Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum in 2013. He is currently Cross-Platform Publishing Associate at Cooper Hewitt. A writer, historian, and designer, he also publishes frequently on theatrical design and history.

Notes

- “About,” Circle Jerk. In June of 2021, Circle Jerk was named a Finalist for the Pulitzer Prize for Drama, likely making it the first digital production to receive this distinction.

- Helen Shaw, “Circle Jerk’s Theatrical Erudition Includes a Dose of The O.C.,” Vulture, October 21, 2020.

- Ibid. Circle Jerk co-creator Michael Breslin further tweeted that he often finds himself writing “theater show” rather than “play” to describe the group’s work.

- Helen Shaw, “Jeremy O. Harris Is Spending HBO’s Money on Producing Plays and May Be Funding the Revolution,” Vulture, November 2, 2020.

- Michael Paulson, “‘It’s More Money Than I Imagined.’ So He’s Giving Some of It Away,” New York Times, December 23, 2020.

Theater Credits

Heroes of the Fourth Turning

By Will Arbery

Directed by Danya Taymor

Lighting design by Isabella Byrd

Sound design by Justin Ellington

Costume design by Sarafina Bush

Original scenic design by Laura Jellinek

Circle Jerk

By Michael Breslin and Patrick Foley

with collaborators Catherine María Rodríguez and Ariel Sibert

Directed by Rory Pelsue