Issue 5 2021 Long Essays

Selling the South

Erica M. Schaumberg

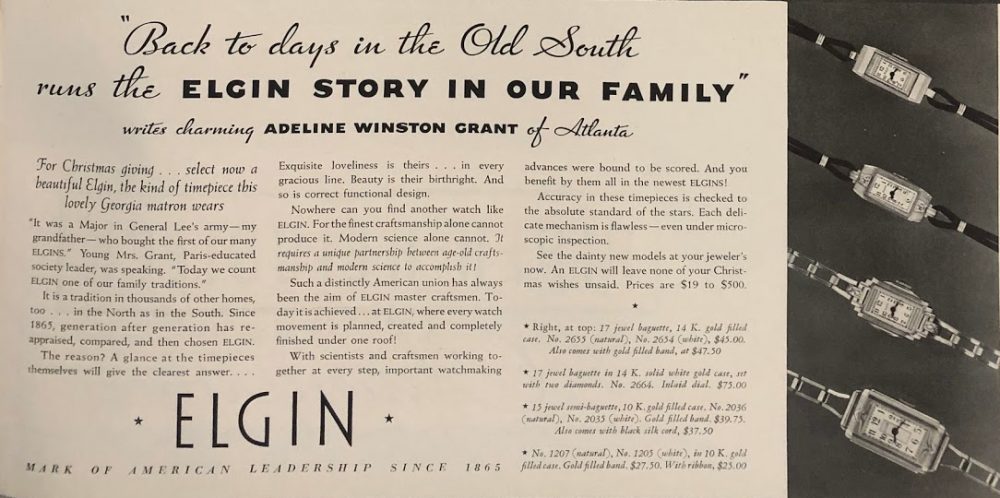

detail of Figure 1 Elgin Watch Company, “Back to Days in the Old South runs the Elgin Story in our Family,” Fortune, December 1934, Cooper Hewitt National Design Library.

The romanticized image of the American South lined with oak trees stretching from one plantation to the next includes an array of figures: heroic Confederate gentlemen, innocent Southern Belles, and enslaved laborers. While statues erected to honor Confederate generals have been criticized and torn down, the perception of the Southern Belle has remained largely untouched. She has appealed to past and contemporary audiences for her purity, sophisticated manners, and innocence. This is evident in popular advertisements for jewelry, silver, and cosmetics, and on social media that promote plantations as a setting for weddings. Popular films, media, and visual culture have fueled this nostalgia for a fictitious telling of history.1

The white Southern Belle, a character loosely based on historical events, has appealed to past and contemporary audiences for her purity, sophisticated manners, and innocence. In reality, White women played an active, even aggressive role in the creation of Southern mythic identity.2 The Lost Cause was a complex, reactionary movement that eased the anxieties of White Southerners after losing the war by making it acceptable to romanticize Southern culture and incorporate it into daily life.3 Groups such as the United Daughters of the Confederacy personified themes of Southern aristocracy and became influential figures who endorsed the spread of Southern idealism through popular culture.4 They financially contributed to and inspired the design of hundreds of monuments across the United States.5 Most significantly, the Southern Belle was cleansed of any notion of violence while she sought to restore an era ingrained with trauma and brutality.6 Recent scholarship has exposed the cruelty inflicted on slaves by their female masters. Slaveholding was taught to girls at a young age as they inherited slaves, bought them as property, witnessed brutal punishments, and were required to be called “mistress,” customs that amplified their racist superiority.7

The twentieth-century epitome of Southern mythology, romanticism and femininity is exemplified by the 1936 publication of Margaret Mitchell’s novel Gone With the Wind. Mitchell attempted to redefine Southern culture to ennoble the future of an American society threatened by the Great Depression and the rise of Nazism and fascism in Europe.8 The book reminded readers of a pastoral ideal rooted in the American experience. The main character, the iconic Scarlett O’Hara, is a flirtatious and manipulative Southern Belle who survives the turbulent politics of the American Civil War and defends her plantation home, Tara.9 Mitchell romanticizes the aristocratic Southern society that venerates Scarlett as a heroine. She articulates America’s trailblazing spirit through Scarlett, who fights back the Union soldiers, re-creates herself after the fall of Atlanta, and marries into aristocratic society to live her American dream. The novel glosses over class, race, and gender issues that have always afflicted American history. African American slaves in the novel remain devoted to Scarlett even after the war. At the time, several critics noted inaccuracies throughout Mitchell’s novel and viewed the publication simply as propaganda for Southern cultural history.10 However, the mixed reviews could not stop the novel, or film made from the book, from becoming a prominent source of American material and visual culture.

The 1939 film Gone With the Wind produced by MGM and starring Vivian Leigh and Clark Gable, like the novel, disseminated propagandistic sentiments about the antebellum South to the world.11 It glorified the antebellum period through its historically inaccurate sets and costumes that enthralled twentieth-century viewers.12 Leigh’s identity, appearance, and style became synonymous with Scarlett’s character and was marketed nationally to middle-class women.13

Scarlett O’Hara represented an ideal of American beauty that was used to market products to female consumers ranging from cosmetics to cocktails. She not only became a symbol of the romanticized South but was also emblematic of feminine behavior that all American women might want to achieve.14 Gone With the Wind and its version of White femininity proved useful to companies that capitalized on the film’s success by releasing a spate of products inspired by the movie. In 1939, Macy’s flagship New York City store turned several floors into recreated scenes from the movie, including Rhett Butler’s Dressing Room and Scarlett’s Bedroom. The theme of Macy’s exhibition, “The Old South Comes North,” successfully promoted the romanticized South through fashion, interiors, and other products of American design.15 While Gone With the Wind should not be regarded as the sole reason for the establishment of Southern idealism in the twentieth century, it did normalize the theme in American culture.16

Other companies marketed products and disseminated cultural values simultaneously. Objects branded with “Dixie” or “Old South” associated themselves with the antebellum era and boosted national consumption of Southern culture along with company profits. Depictions of elite Southern women illustrated appropriate social behavior that sold a standard of leisure and sophistication branded as purely American when in fact they were rooted in an idealized world of Southern aristocracy drained of reality.17

Fig. 1 Elgin Watch Company, “Back to Days in the Old South runs the Elgin Story in our Family,” Fortune, December 1934, Cooper Hewitt National Design Library.

The advertisement for Elgin Watches published in the December 1934 Fortune magazine is a case in point. It focuses on a White woman wearing an Elgin watch (Fig. 1). Outfitted in a tulle and satin gown with exaggerated sleeves, she sits on a tufted ottoman holding a white flower. Her pulled-back hair is ornamented with a brooch while she wears a single string of pearls around her neck. A series of bracelets on her right wrist and wedding band complete her attire. Below the photograph is a story entitled “Back to days in the Old South runs the Elgin Story in our Family.” The copy by Adeline Winston Grant describes her connection to the Elgin National Watch Company as going back to her grandfather’s purchase of a watch when he was a major in General Lee’s military. Grant describes the triumph of the company as a great union between modern technology and American craftsmanship. The creation of a narrative using General Robert E. Lee, the Confederate Army, and antebellum Atlanta is meant to attach the product to Southern American history and uses the Southern Belle intentionally as an extension of the Old South familiar to consumers through popular culture.18 The product is more prestigious for its links to historical names and events. However, the advertisement should be examined for its inauthenticity, as Grant is only loosely connected to Southern identity and the Elgin National Watch Company was based in Illinois between 1865 and the 1960s.19

Fig. 2 Old South Perfumers, “The Romance that Lives Forever,” Woman’s Home Companion, 1946, Duke University.

Old South Perfumers capitalized on Southern heritage in combination with American glamour by creating a line of perfumes referencing its regional culture (Fig. 2). Using names such as Cotton Blossom, Virginia Reel, Plantation Garden, and Natchez Rose, the fragrances were featured in Woman’s Home Companion in 1946 and personified by a Southern lady being embraced by her Confederate officer lover. The woman leans against a fluted column while the man lovingly holds her hand. The officer’s horse is tied to a post in a landscape ornamented with blossoming flowers and trees leading to the edge of the water where a river boat cruises along. The text reads: “Only once in the world has there been the loveliness, the easy grandeur of the Old South, whose romance lives again in these exquisite toilet luxuries.” Old South Perfumers exaggerated romance by setting it against the charm of the Southern plantation.

Elgin National Watch Company and Old South Perfumes both manufactured a mythical heritage for their product. Lest one think this consumerist strategy has disappeared, one need only look to the contemporary era and those dreaming of getting married on historic plantations. When examined on Instagram, the phrase “Southern Bride” is tagged in over 500,000 posts. The phenomenon of the plantation wedding is common to social media and to celebrities featured in wedding magazines. A plantation wedding combines the modern connotations of American weddings as new beginnings while also personifying a historical legacy by means of location.

Charleston, South Carolina, is a popular Southern wedding destination as it offers a surplus of popular plantation homes and historic sites. Runnymede Plantation is one example. The property, nestled between magnolia trees and the Ashley River, was founded in 1705. In 1865, however, the mansion was destroyed and set on fire by Union troops. Later rebuilt, it suffered another fire in 2002, leaving only the property’s recognizable two-story brick chimney, brick steps, and original bell from 1704.20 Runnymede Plantation has earned 4.9 stars out of 5 on both The Knot and WeddingWire, two wedding websites. Reviews note the beautiful views as offering an unforgettable experience amongst the plantation’s ruins. The property is undeniably striking for its landscape with twisting trees, but the site is gnarled with its historical past.

Southern plantations like Gone With the Wind’s beloved Tara are linked to the purity of Southern femininity; their lush landscapes with large oak trees framing and enclosing the home and property are reminiscent of the hoop skirts encasing the female figure of the nineteenth century.21 However aesthetically beautiful plantations may be, they are inherently and historically traumatic and violent. African Americans were bought, sold, inherited, and enslaved on such plantations. Regarded as property, they were never themselves allowed to legally marry. White femininity in particular accounts for the lynching of Black men well into the mid-twentieth century.22 Applying this history to a contemporary context, it is alarming that people would choose such a highly charged location for weddings. These locations freeze the meaning of Southern aristocracy within fraught Southern traditions.23 Brides and grooms signify new beginnings and union; the role of plantations in American culture is complicated and should be re-examined as locations for such beginnings.

On December 5, 2019, Pinterest and Knot Worldwide released statements acknowledging the troublesome imagery of plantation weddings featured on their websites. Their responses were the result of efforts by the civil rights advocacy group Color of Change. Pinterest has taken action to limit the distribution of plantation wedding content on their platform and Knot Worldwide has stated its intention to educate vendors by accurately describing the historical significance of plantations.24 These steps by Pinterest and the Knot Worldwide illustrate a desire for accountability, to contextualize the complex history of plantations. Reflecting on the ideas of the Lost Cause and Southern romanticism, it is crucial to evaluate the contemporary use of plantations—given their historical role in promoting an idealized vision of Southern history that excludes people of color and the violence wreaked on them within American society.

As for the movie Gone With the Wind, following the George Floyd protests in the summer of 2020, media streaming services including Disney+ and HBO Max have supplemented such films with disclaimers acknowledging its stereotypical depictions.25 The Southern Belle may always be intertwined with the idealized South as a consumable product, but such disclaimers can alert Americans to her flawed history. American material and visual culture need to be continually examined for how they articulate the torturous history of freedom and inequality through design.

received her MA from Parsons School of Design in 2020 and her BA from Gettysburg College in 2018. Throughout her education at Gettysburg she worked extensively at the Schmucker Art Gallery. Currently, Erica and fellow alum Virginia Pollock are collaborating on an Instagram account and podcast dedicated to making the study of art and design easily accessible, relatable, inclusive, and approachable.

Notes

- David Lowenthal, The Past is a Foreign Country—Revisited (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015), 33–2.

- Tara McPherson, Reconstructing Dixie: Race, Gender, and Nostalgia in the Imagined South (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003), 49.

- Jane Turner Censer, The Reconstruction of White Southern Womanhood 1865–1895 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2003), 763.

- W. Fitzhugh Brundage, “Contentious and Collected: Memory’s Future in Southern History,” The Journal of Southern History 75, no. 3 (2009): 762.

- The Confederate statues financed by organizations like the United Daughters of the Confederacy fill a void crafted by the Lost Cause. Women are often the subjects of such monuments, portrayed as the allegorical figures Liberty, Victory, or Glory who were more associated with depictions of goddesses from classical antiquity than their nineteenth-century conservative counterparts. The influence of classical antiquity on such statues personified the canonized White body. The statues minimized the Confederacy’s defeat and utilized the female body to depict Southern strength and heroism through traditional classicism. Rebecca Senior, “The Confederate statues that have been overlooked: Anonymous women,” The Washington Post, July 10, 2020.

- Tara McPherson, Reconstructing Dixie, 3.

- Stephanie E. Jones-Rogers, They Were Her Property: White Women as Slave Owners in the American South (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2020), xii, xv.

- Amanda Adams, “‘Painfully Southern’: Gone with the Wind, the Agrarians, and the Battle for the New South,” The Southern Literary Journal 40, no. 1 (2007): 58.

- Inspired by the Georgia mansion, The Twelve Oaks, Gone With the Wind’s Tara was built on a soundstage. The Twelve Oaks, originally built in 1836 and renovated in 2012, currently functions as a bed and breakfast. It has been used as the location for ten movies and television series. Guests are welcomed to stay in suites called Cannonball Run, In the Heat of the Night, and The Frankly Scarlett. The mansion offers wedding and private event opportunities. It has been featured in publications and media outlets including The Knot, WeddingWire, and Southern Living. “The Twelve Oaks,” The Twelve Oaks, accessed January 14, 2021.

- Amanda Adams, “‘Painfully Southern,’” 60.

- Helen Taylor, Scarlett’s Women: “Gone With the Wind” and its Female Fans (London: Virago Press Ltd, 2014), n.p.

- Lou Taylor, The Study of Dress History (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2002), 180, 185.

- Biographers parallel Scarlett’s flirtatious and manipulative personality to Vivian Leigh’s often chaotic and unstable lifestyle. Leigh experienced manic-depressive behavior, tuberculosis, insomnia, and alcoholism throughout her career. Her beauty and femininity would become fashionable attributes for female consumers. Taylor, Scarlett’s Women, n.p.

- Karen L. Cox, Dreaming of Dixie: How the South was Created in American Pop Culture (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011), 53.

- Ibid., 51–2.

- Gone With the Wind and Southern romanticism influenced American consumerism, fashion, and design. Between the 1930s and1960s Vogue and Women’s Wear Daily published many articles and advertisements referencing Southern idealism. In the article “Chic After Dixie,” published 1932, Vogue showcases cotton bags with silver metal trimming from Bergdorf Goodman and golf dresses from Saks-Fifth Avenue to add “A Little of the glamour of old Dixie plantation life” to the modern woman. Macy’s advertised the success of their “Old South Comes North” exhibition in Women’s Wear Daily by reporting that 1,400 “Gone With the Wind” uniforms were sold in two days. The uniforms retailed for $1.83 and came in Melanie white, O’Hara green, Bonnie blue, and Tara wine. Olympic Knitwear Inc. designed the Scarlett O’Hara Sweater, asserting it was “The most sensational sweater ‘scoop’ for 1940.” It was sold in a variety of colors including Scarlett Red, Colonial White, and Mammy Black. Products advertised and sold through American retailers amplified the influence of Southern romanticism rooted in racism. “Chic After Dixie,” Vogue, June 1, 1932, 46; “Washable Dresses: Macy’s Hails Success Of ‘Gone With the Wind’ Uniforms At $1.83,” Women’s Wear Daily, March 14, 1940, 17; “Gone With the Wind (Olympic Knitwear, Inc.),” Women’s Wear Daily, December 27, 1939, 11.

- Cox, Dreaming of Dixie, 34, 36, 39.

- Ibid., 36–7.

- The New York Times reported in September 1934 that Grant’s family lived at 67 Park Avenue in Manhattan. Grant was a graduate of the Washington Seminary in Atlanta, attended the Finch School in New York City, was presented at the Court of St. James in 1929, and made her debut in Atlanta in 1930. By the time the advertisement was published in December of 1934, Grant married, Berry Grant, a member of the Harvard Club of New York, alumni of Phillips Andover, Georgia School of Technology, and Harvard Business School. He was connected with the brokerage firm, Hornblower & Weeks in New York City. They married on Governors Island in 1934 and resided at 30 Park Avenue in Manhattan following their wedding.

- “History,” Runnymede Events, accessed December 1, 2019.

- McPherson, Reconstructing Dixie, 42.

- Emma Coleman Jordan, “Crossing the River of Blood Between Us: Lynching, Violence, Beauty, and the Paradox of Feminist History,” The Journal of Gender, Race & Justice 3, no. 2 (Spring 2000): 568, 571.

- McPherson, Reconstructing Dixie, 44.

- Michael Brice-Saddler, “Wedding vendors romanticize slave plantations. The Knot and Pinterest will no longer promote them,” The Washington Post, December 5, 2019.

- Kirsten Acuna, “‘Gone With the Wind’ is back on HBO Max with a video disclaimer warning the film ‘denies the horrors of slavery,’” Insider, June 24, 2020.