Grace: An Inclusive Fashion Collection

The roughly 3.3 million wheelchair users in Europe represent an emerging market 1. In order to help them, designers need to engage the specific needs of these consumers in their design process. New technologies, such as 3D body scanning, have proved to be very useful to understand the specific variations in body size and patterns. The first category of wheelchair users with high paraplegia have no ability to dress themselves; the second category can not use their legs, but feel completely free and mobile with the wheelchair. In both categories, the body dimensions can be very different.

Increasingly, 3D body scanning has been used to map variations in size and body dimensions of wheelchair users 2. First, there are disabled people with a body shape identical to abled-bodied people. For these people the existing clothing size charts can be used – only an adaption of existing pattern systems is needed to make them appropriate and comfortable for the seated person. Secondly, there are disabled wheelchair users with a body shape that has changed due to sitting and dystrophy of the legs. Most wheelchairs users fall into this category where the abdomen is often thicker and legs have become thin due to hypotrophy. The last category contains disabled people with a deviating body shape, for example, asymmetry. For this group, custom-made patterns have to be developed. Specially designed clothing for wheelchair-users can be helpful and beneficial. Wang a.o. showed that good customized clothing could reduce a toilet visit time by 46% and undressing time by 25% 3.

Well-being in clothing is not only defined by the right form and functionality of clothing. In the same way as abled people do, wheelchair users want to express themselves with nice and distinctive clothing 4. However, many wheelchair users have difficulties to find nice and comfortable clothing, not only due to fit and functionality problems, but also to limited access to stores that are wheelchair user-friendly 5. To fully understand clothing behaviour and clothing desires of people in wheelchairs, one needs to discern five important themes: form and function, self-expression, social identity, self-reliance and symbols of victory 6. “Each disabled person must be seen as an individual with a distinct set of physical and psychological limitations and each garment designed and produced for that individual must take all of these limitations into account,” explain Renee Weiss Chase and M. Dolores Quinn, in their early study on disability and design Simplicity’s design without limits. Designing and sewing for special needs 7. In this definition, the view of clothing for the disabled is holistic, physical and psychological, and built at the individual level. They make an explicit reference to the sense of self and identity, proposing that it is based on physical, intellectual and social elements, including a strong sense of how self-perception is defined by how others see us 8. They go on to explore the effect of becoming disabled on self-esteem, stating, “When a person becomes disabled the perception of self is often confused, damaged or even lost… the person goes through grief and mourning. This process hopefully results in … a willingness to rebuild a sense of self and self-esteem,” 9. The inspiration of GRACE is built on this holistic concept whilst using the outcomes of the other work packages.

Research methodology

The design research project is part of a cross-disciplinary research project, where anthropometric science was involved to generate information on the specific needs and body measurements of people in wheelchairs by using 3D body scans. In the second work, package surveys and interviews were set out to gain more insight in the wishes of wheelchair-users 10. For the pilot project GRACE, the results of both research outcomes were used as the start of a design research project, an iterative research project, where the end product, a pilot fashion collection, is an artefact – where the thinking is so to speak, embodied in the artefact, and where the goal is not primarily communicable knowledge in the sense of verbal communication, but in the sense of visual or iconic or imagistic communication 11. We will describe and explain here the iterative design process, and illustrate how the outcomes of the two other work packages are naturally interwoven in the reflection of the design process.

Developing the concept for GRACE

Initial research started by searching for a new pattern-cutting approach. Soon, however, we discovered that this was already covered by other brands, such as A Body Issue, Arnhem, and other earlier approaches of making clothing for disabled people developed throughout history. Previous research submitted by I. Petcu suggested that seated people did not want any more highlights to their difference 12. The interview results along with the existing theoretical literature showed that many seated people did not want clothing to be specially cut for them 13. They had had enough of being ‘different’ and ‘other,’ and wished to dress just like any other person would. They had the same desires as someone who is standing: to look fashionable, attractive, hide flaws, keep warm, look sexy, etc. This led to the starting point for the design research part: fashion do not need to go over to the world of seated people and ‘rescue’ them from bad design. Instead, it could include the specific needs of seated people in its design process. Seated people do not need rescuing, they just need their needs and their world to be included in the broader conversation: inclusion 14. They wanted to be able to join abled bodied people, and dress the same, with the same concerns: attractiveness, fashionable, sexy, comfort, glamour, luxury, etc.

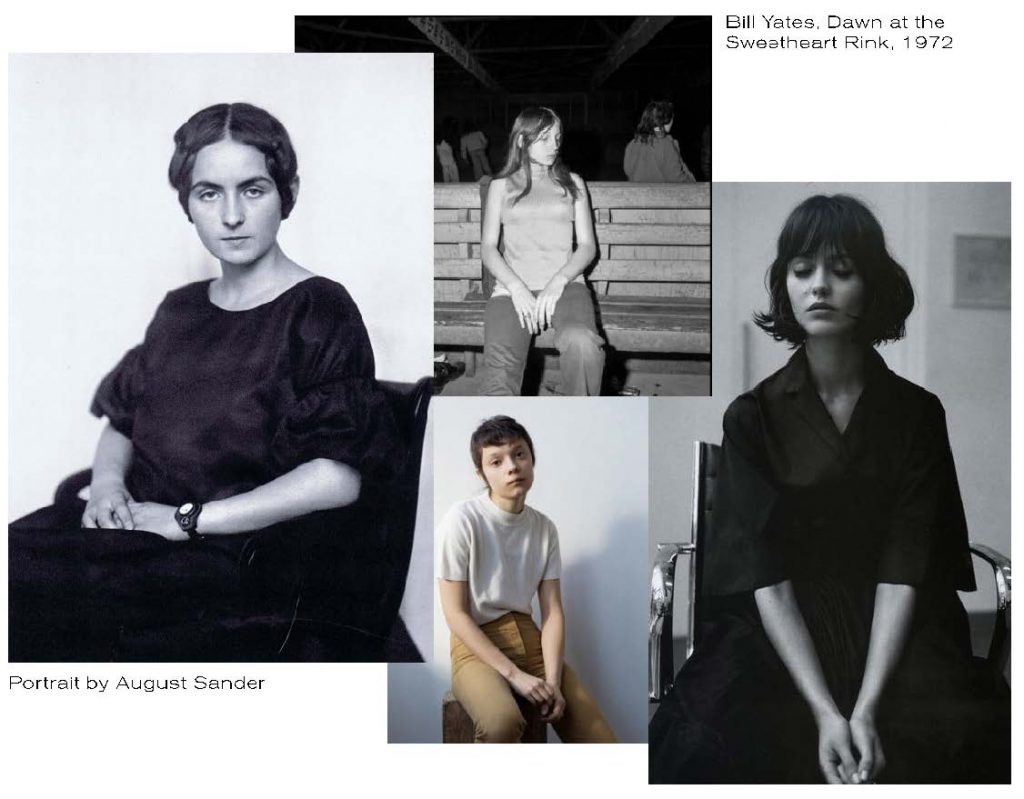

This result made us decide to treat the design project like any other fashion design process, but starting with being seated as the initial focus (rather than being disabled). So, we looked at the proportion of the body in this position, and issues of comfort, but we did not dwell on them. We looked at the atmosphere of being seated: in repose, gracefulness, stillness, contemplation, peace, rest, etc.

Primarily, GRACE is about an aesthetic viewpoint – it started with the simplest actions while being seated, and developed from there a subtle exploration of what that means and how this might impact the design of clothing. The title comes from my personal interest in gracefulness, as a state of being, that is utterly distinct from the more oft cited and fashionable term, ‘Elegance’. In our current visual culture, aesthetic elegance objectifies and prepares a woman to be acceptable for the male gaze 15. Gracefulness, on the other hand, is something else entirely. It is a state of being, a feeling of solidity and calmness borne of a strong sense of self. Grace is founded on strength and balance. To be seated, to be in repose, is to be grounded, settled, and with strong roots. So, our collection GRACE, is primarily a high end fashion collection, taking inspiration from this seated position, and aiming to be comfortable, functional, and making use of an imagery that is calmer, and more, still than the usual, energetic and objectifying position of traditional fashion collections and photo shoots.

The role of pattern-cutting

As a part of the design process we naturally applied pattern-cutting processes and fitting approaches based on research by A Body Issue, conducted with the use of 3D body scanning and others 16. We were aware that able-bodied people, also, have issues with ready to wear clothing: plus size, long arms, no waist, large feet, etc. The ready-to-wear fashion industry often avoids catering to these people and has focused on an ideal, average figure (often focussing on young white women to the exclusion of others). This seems to be an issue of marketing: is it feasible to offer more specialised clothing to a smaller market? Options for people who don’t fit standard sizes are outsize clothing, baggy sportswear, like t-shirts and tracksuit bottoms, or made-to-measure clothing which is expensive.

This insight led to the decision to pull back from cutting the clothes too closely to the seated figure, to allow standing people to also wear them. There is a slight idiosyncrasy to the clothes when worn by people standing up, which has a fashionable feel – slightly ill-fitting yet in a cool way. Based on that information, we altered the cut of garments to help them sit better on the body whilst seated, but also keeping in mind that people who stood could also wear them – just as seated people wear clothing cut for those who stand, why not the reverse?

At the same time, we did not want to focus primarily on pattern-cutting approaches, to avoid sending the garments off on a tangent into ‘weird’ clothing territory. If we had focussed entirely on cutting clothing to follow the exact shape of the seated figure, then the garment shapes would have become quite extreme and far removed from what we normally recognise as contemporary clothing. To my mind, it is neither necessary, nor, in fact, desirable to go that far. Clothing cut for the standing figure is made to be wearable in different situations – the ability to raise one’s arm about the head is considered and is more easily achieved in certain garments, a T-shirt for example. However, it is not necessary to cut such movement into every garment. Likewise, clothing cut for the standing figure functions pretty well whilst a person is seated. It works because this person can stand and adjust themselves if necessary. Of course, a disabled person does not have that luxury, so their needs must be included in the garment, but not at the expense of its attractiveness. That is the whole objective of designing this collection – to be both functional and attractive. To that end, my pattern cutting approach utilised some of the techniques developed by A Body Issue, but then pulled back from them, to keep the garments in the realms of standard clothing, which also allows the garments to be worn by someone who is not confined to a wheelchair.

To make a more luxurious collection, we avoided stretchy jerseys and used more traditional textiles: cotton drill, wool suiting, denim, cotton poplin, etc. In cases we did use jersey; a luxury textile from Paris without Elastane. To optimize the conformability of the collection, the following specific pattern cutting and design consideration were used:

- Trousers and skirts are cut with a long back rise (crotch) and short front is raised.

- Tops, blouses, T-shirts and jackets, all are cut on a seated figure with a slouch (we do not sit bolt upright.) Armholes are moved around more to the front, and back is increased in length.

- Back armhole is lengthened and neck is moved forward slightly.

- Gussets are added into side seams that allow front of garment to rest better on legs. Gussets can be closed for someone standing.

- Gusset is inserted in armhole of traditional blazer to allow for wheeling movement in wheelchair.

- Knitwear is developed with reinforced sections at armhole and elbow to avoid wear 17.

- Trousers and skirts are narrow to avoid fabric getting caught in wheels. No fabric bunching around waist.

- Hems on some short pieces are cut at an angle to give a more attractive look.

- Proportions are considered from seated perspective: shorted tops, and ¾ length trousers and skirts to break up body proportions.

- Natural textiles are used where possible; some polyester is used for crease resistance.

The result is primarily a high-end fashion collection. Of course, price is an issue for disabled people who often do not have disposable income, but the pilot collection was mainly designed as a proposal on how a collection designed with wheelchair users in mind could be, from a fashionable and aesthetic point of view.

Conclusion

From the pilot collection GRACE, created as a part of this cross-disciplinary research project on people in wheelchairs, we could derive the following conclusions. People seated in wheelchairs do not want their disability to be the focus of how they dress themselves. It does not define them, and they would often prefer it to be hidden, or to be of no issue. They do not want clothes that draw attention to their disabilities, or remind them or others, of being different or not ‘normal.’ The problems they face in dressing themselves are much the same as those experienced by other types of people – those who are very tall, or large, with long arms, or a stoop, or with outsized feet. Thus, the five important values that Hodges and Yurchisin discerned for people in wheelchairs – form and function, self-expression, social identity, self-reliance and symbols of victory – are also relevant for able-bodied people 18. It is clear that, clothing design and the world of fashion can take steps towards producing garments, and desirable brand identities that appeal to a larger and more inclusive group of people. And beyond, this helps us to escape conventional fashion discourse and aesthetic; using a new and fresh starting point the pilot GRACE helps us to define new imagery and aesthetics that escape the classical and narrow visual representations of the fashionable woman and man in general.

REFERENCES

1 L. H. V. van der Woude, S. de Groot, & T. W. J. Janssen, (2006). Manual wheelchairs: Research and innovation in rehabilitation, sports, daily life and health. Medical Engineering and Physics, 28(9), 905-915. doi:10.1016/j.medengphy.2005.12.001.

2 V. Paquet, & D. Feathers, (2004). “An anthropometric study of manual and powered wheelchair users.” In International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics, 33(3), 191-204. doi:10.1016/j.ergon.2003.10.003; A. McCormick, M. Brien, J. Plourde, E. Wood, P. Rosenbaum, & J. McLean, (2007). Stability of the gross motor function classification system in adults with cerebral palsy. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 49(4), 265-269. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2007.00265.x; S. M. Tweedy, & Y. C. Vanlandewijck, (2011). International paralympic committee position stand-background and scientific principles of classification in paralympic sport. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 45(4), 259-269. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2009.065060.

3 Y. Wang, D. Wu, M. Zhao, & J. Li, (2014). Evaluation on an ergonomic design of functional clothing for wheelchair users. Applied Ergonomics, 45(3), 550-555. doi:10.1016/j.apergo.2013.07.010.

4 J. M. Lamb, (2001). “Disability and the social importance of appearance.” Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, 19(3), 134-143.

5 M. Thorén, (1996). “Systems approach to clothing for disabled users. why is it difficult for disabled users to find suitable clothing.” Applied Ergonomics, 27(6), 389-396. doi:10.1016/S0003-6870(96)00029-4.

6 H. J. Chang, N. Hodges, & J. Yurchisin, (2014). “Consumers with disabilities: A qualitative exploration of clothing selection and use among female college students.” Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, 32(1), 34-48. doi:10.1177/0887302X13513325.

7 R. Weiss Chase and M. Dolores Quinn, (1990) Simplicity’s design without limits. Designing and sewing for special needs,Simplicity Patterns Co.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

10 L. Vonk, Virtual Sizing. (2017) forthcoming.

11 Christopher Frayling, (1993). “Research in Art and Design.” Royal College of Art Research papers, vol 1 nr 1.

12 PhD, Saxion University of Applied Sciences

13 Vonk a.o., Virtual Sizing; Chase and Quinn, Simplicity’s design without limits, 3.

14 Chase and Quinn, Simplicity’s design without limits, 3.

15 L. Mulvey, (1975). Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema. Screen. Oxford Journals, 16.

16 A. Rudolf, A. Cupar, T. Kozar, & Z. Stjepanovic, (2015). Study regarding the virtual prototyping of garments for paraplegics. Fibers and Polymers, 16(5), 1177-1192. doi:10.1007/s12221-015-1177-4.

17 Developed by I. Petcu PhD, Saxion University of Applied Sciences.

18 Chang, Hodges, & Yurchisin, “Consumers with disabilities.”

PULL QUOTE

“People seated in wheelchairs do not want their disability to be the focus of how they dress themselves. It does not define them.”