On Love, Affection, and Cities

Paula de Oliveira Camargo

Introduction

This paper is an attempt to address research practices in design in light of personal experiences with the city environment. Understanding that choice in the realm of design, architecture, and urban studies is professionally informed by how people experience their everyday surroundings, these experiences—which can be violent, pleasurable, or even both—can lead to a better understanding of the city environment. In the process, they leave marks, imprints, and evidence of collaboration on the urban ground.

A designer’s experience in the city is deeply linked to places where they develop affection. Nonetheless, many times urbanity throws itself back at researchers and practitioners alike, resisting categorization. This paper is the result of Rio de Janeiro throwing itself back at me, a PhD candidate in design studies and policies interested in exploring relationships between people and the built environment (as well as the ways in which these interactions inscribe and prescribe behavior).

The poetic text composed brings together different aspects of my “being-in-the-world,” through a personal experience of seeing the world through Rio. This gaze is defined by my experience of being an architect, urbanist, design researcher, civil servant, working-woman, runner, mother, and a citizen. It is the gaze of the carioca1 who delves in the districts of Méier, Cachambi, Barra, Leblon, Santa Teresa, Botafogo, and Jardim Botânico (not necessarily in that order).2 Above all, it is the gaze of the human I am in the city.3

The research method I used was developed personally and organically from noticing things on the street, taking photos of these things, and publishing them on my personal Instagram account. After recognizing the curatorial threads present in these images, I began to articulate the value of noticing and wanted to question how important or extended this action goes in studies of the urban environment. Through platforms such as Instagram, the potential for noticing is increased, but it is also a tool for seeing who else in society is noticing similar patterns in the urban fabric in similar ways, based on framing, composition, and subject matter. By posting these images, I wasn’t aiming at any specific academic, artistic, or documental agenda. When I began taking photos of urban details I noticed in Rio, they were just for personal enjoyment and consumption between me and my friends, but as I noticed patterns in the practice of taking these pictures, I tried to dissect the images and their meanings in alternative ways.

Some objects have been intentionally placed on the ground for interaction—becoming images in other people’s frames—very much like a landscape photo site, but on the ground. On the other hand, some other objects could only turn into images if noticed, framed, and even tagged on the platform. It was my understanding that the images I had gathered could be treated not only as individual posts on social media, but as an ensemble that, together, curated meaning. The meaning analyzed was mostly in the collection and the motivation for taking the pictures.

An important part of this process I began experimenting with in a more serious way was comprehending that there is a certain something that brings these images together. This something is, for me, an attentional4 gaze that relates to the city, achieved during the action of walking.

Being an active member at the Laboratory of Design and Anthropology (LaDA)5 research group, I have presented two different versions of this text previously. The first was a piece written as part of a group exercise with the objective of addressing academic writing in diverse, plural ways. The second was presented orally at LaDA’s Entremeios seminar in 2018, in a conversation circle I organized to debate how different dimensions of time, city, and affection can surface through language, writing, research, and design. This is the latest— but never final—version of this text, in which theory, research, and debate on cities mingle with personal reflection and affection.

On Love, Affection, and Cities

Cities are places of affection.

Of affecting and of being affected.6

To be in the city is to be with people. Thousands. Millions. Inhabitants. Visitors. Passersby.

To be in the city is to share territorial knowledge with strangers, as equals and not-always-equals. To be a part of a community can, at times, be gregarious and segregating.

Many versions of cities can coexist in time and place. A city can be a violent place as well as a safe haven—a place of carelessness and care, of getting lost and of finding oneself—of disaffection and affection, of life and death—but perhaps, most importantly, life.

Human life is only viable in coexistence with the vitality of matter beyond the human body, (such as proposed by Bennett, 2010)7—life that circulates “around and within human bodies.”8 As humans (not disregarding the long lists of intersectional differences between us), we intuitively understand that to “be” in the world, we must inhabit it. But can we really? Are we entitled to? Has living in the so-called Anthropocene led to human feelings of superiority over other species and matter? Political, cultural, gendered, racial, and environmental agendas cross and intersect, showing that being human is not a given, but a complex status, full of matter internally and externally. As such, it cannot be regarded as one, but as many lives within the humanity of being on Earth. Yet we dare to build human settlements to address the needs and anxieties of this human species, disregarding the vitality of matter.

To eat, study, work, think, sleep, play, desire, suffer, move around, travel, fuck, live, die.

To love.

Actions of existence that may be bounded and, perhaps, incarcerated in a given city.

At some point in history, (some) humans understood that they were entitled to consciously alter the world in time. They adapted the existing world to their needs, real or imagined, driven by a will to believe that a certain type of spatial configuration and geographical location would suit these needs. These humans, who we identify with, designated specific sites for specific purposes. We have visible and invisible borders of entry that designate who can be where and for how much—especially for how much.

Existence in the city is monetized. Connections present barriers that we use to create spaces of inclusion and exclusion in cities at all times, based on how much money or resources can be spent to perform any given action.

Living in cities has become so commonplace that questioning its oddities is a rare occurrence.9 More often than not the thought about the existence of cities per se is taken for granted. A world without cities does not seem likely at all.

We have created the system and adapted to the system. We manage the system. We live in the system.

Do we question the system?

The city may be a space barren of meanings. The city may be a hard, challenging, harsh environment.

Who is allowed a right to the city?

Are we a numb society?

***

Cities seem to be environments where excess flourishes as human experience. Not surprisingly, diagnoses of mental illnesses escalate, making cities places of medicated people. Harsh, dour environments where the excess of information seems, also, unavoidable.

Traces of this excess are, thus, all over in urban agglomerations. It reaches the inside of the inhabitants of cities. Stimuli. Too much content. Too many impulses.

Be. Buy. Have. Come.

To be in a place, but never really experience it—unless through mediation. To exist, but never in person in physical spaces. Screens and social media take over the embodiment of life. Structural rupture, fragmentation, the disruption of attention.10 Constant, consistent bombing of information. Propaganda. We walk, faces fixed on screens. We bump into each other. Headphones. We stumble, erratically walking.

What are we looking for? Is being outside not enough? Is there an outside?

Looking up is—almost always—promising. Soothing. Emptying from the excesses. The sky. Blue, gray, leaden, pink. Treetops. Green, yellow, red, brown. The moon. Crescent, full, waning, new. The sun that blinds the eye.

Looking up promises the emptiness for the soul to escape the nauseous positivity.

However, it is so often the ground that catches the eye…

The ground.

The pavement.

The hole.

Not to stumble.

Not to get our feet wet.

Not to see the others.

Not to look in their eyes.

Not to fall.

To hide.

For no one to see.

To be safe.

Not to suffer.

Not to stop.

Stop.

Just stop.

***

Walking in disattention,11 eyes on the ground, I find messages of love. Of delicacy. Of affection. Messages that affect. Messages by which one can be affected, and through which one can affect and create other affections. Active affections.

Messages for being with, together, in between.

Invitations.

To be attentive. To appreciate. To respond.12 To live.

The bodies we inhabit are in presumptuous dependencies of structures we have co-created.

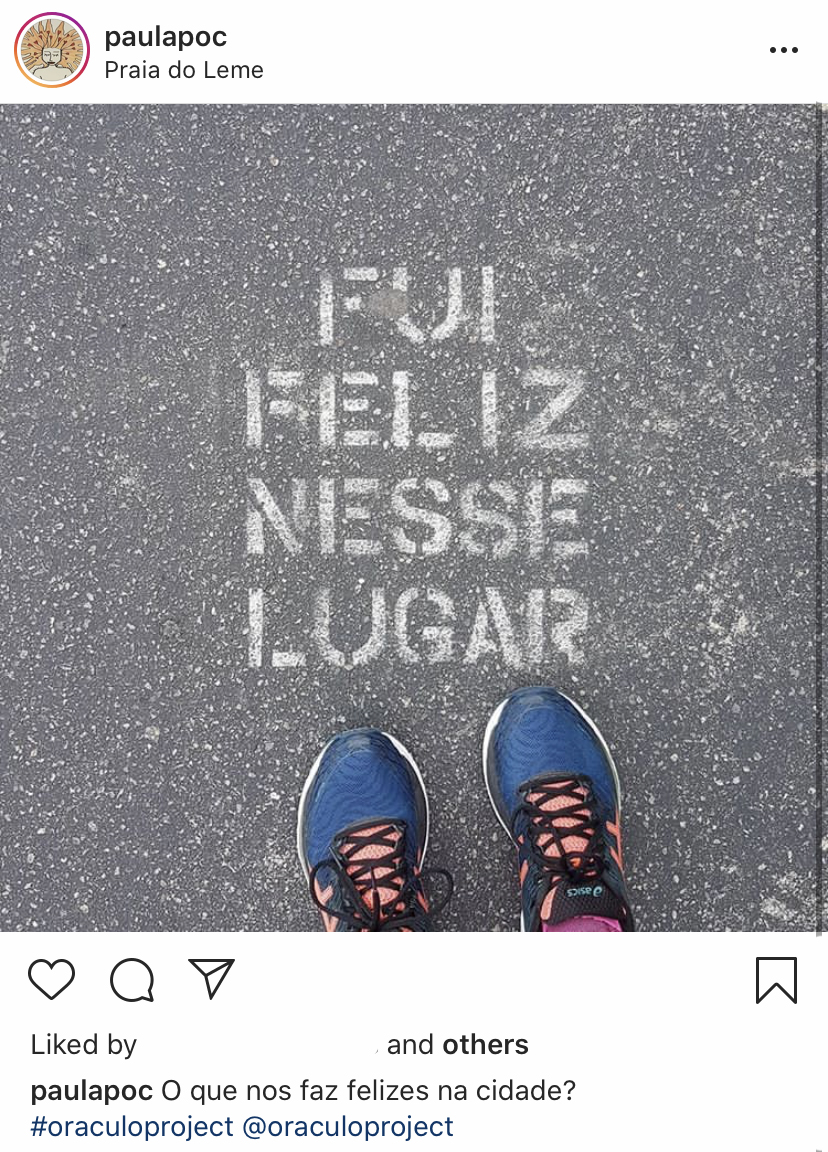

Happy Here

Figure 1. “Fui Feliz Nesse Lugar (I Was Happy in This Site).” Artistic intervention by @oraculoproject in Leme Beach. Paula de Oliveira Camargo, Rio de Janeiro, 2018. Courtesy of Instagram.

We are not alone in the territory. (Fig. 1) We have webs of relationships, agencies, and potencies that surround all things with which we co-exist. We don’t need to “choose between the Apocalypse and the radiant future.”13 We co-live within the city. This active, agentic and inclusive co-living of all beings turns common existence into a defining experience that shapes our understanding of how to perceive the world, how to be in the world, and how to find a place in it.

We exist. Together.

We live. Together.

We are. Together.

What brings us together?

Territory? Geographical limits? Lines on a map?

***

There is something that gives us a sense of belonging, identification with a place, a neighborhood, a district, a city. Perhaps it’s a certain strangeness and affective sense of comfort that coexist in the dense time of a life.

I have grown up knowing those streets. Those houses. Those trees. That neighbor’s dog. That other neighbor who spends every single afternoon fixing his motorbike. That lady who sings while watering plants before work. The car with the metallic speakers announcing, ever at the same hour, that you can sell them your junk. That (a bit scary) route where there is always some kind of Candomblé or Umbanda offering on the crossroads.14 That other route that is a bit longer, but it leads to the best bakery with the best cheese-bread. That movie theater turned into a church. The house that belonged to Grandma’s old friend still stands strong and is now the only original house left among the identical houses built over the site, including where Grandma and Grandpa used to live. The confectionery where I would have mango ice cream turned into a bank. The haberdashery persists on site. The movie theater is still a movie theater but now shows internationally acclaimed indie movies instead of the porn titles that made no sense for me as a kid.

This is evidence of the co-existence of human and urban things together—ever-changing in time and space, transforming and (re)surfacing affections.

Drops of happiness associated with territories of affection.

One may move. One may change.

New, overlapping references and memories from these little private inventories of historical and cultural heritage of human lives on Earth. It’s no small feat.

But we walk, in the “now,” eyes on the ground.

We travel looking at screens.

Submerged, drowned, in the excruciating positiveness.15

But lo, eyes still on the ground, I see the message of love.

Amor (Love)

Figure 2. “Amor (Love).” Sidewalk at Voluntários da Pátria Street, Botafogo. Paula de Oliveira Camargo, Rio de Janeiro, 2018. Courtesy of Instagram.

I posted this image (Fig. 2) on Instagram with the caption “Urban delicacies: what really matters.”

A sidewalk. A rainy day in Botafogo, the district where I live in Rio de Janeiro. In Botafogo, sidewalks widen and narrow irregularly, giving pedestrians a hard time to move around (especially during rush hour). The flowing of buses and vehicles is what really matters, right?

A patch, made in cement over the sidewalk’s pattern, bears the inscription “AMOR” (LOVE). The sidewalk, which is rough and bumpy in so many places, has been re-leveled in that specific spot. The gesture is, itself, an act of love. Toward the city, toward people, toward sidewalks, toward an existence in the micro, in everyday life.

Yet there is still more love in this message.

This small, simple, and unique intervention can have so many diverse meanings. Superimpositions of urban layers over which someone has decided to intervene while the cement was still fresh in order to leave a message for the down lookers.

Here was an opportunity to express LOVE. For a person. For a street. For a community. For a city.

LOVE is there.

Upon seeing LOVE spelled on the patched ground, passersby are given an opportunity to act—to register, reverberate, spread that love. To emanate love for the city, for life in the city, through the registering of a gesture not intended to be ephemeral. Using this sickening excess of information, we now notice positivity, technology, information, image, and even over communication coalesce. By creating another image, I magnify the message of LOVE. Yes, LOVE is there. The screen pictures the image on the sidewalk.

Heart

Figure 3. “Coração (Heart).” Sidewalk at Gago Coutinho Street, Laranjeiras. Paula de Oliveira Camargo, Rio de Janeiro, 2016. Courtesy of Instagram.

This picture (Fig. 3) brings another image of love, but different from the previous one (Fig. 2). This image shows a hole in the ground—a gap on the pavement of Portuguese mosaic stones, which is so typical of the streets of Rio, including those in the Laranjeiras district, where I work.

Gap. Flaw. Defect. Imperfection. Form arises from imperfection. The heart—a symbol of love, but also the organ that allows us life through its constant beats. Expansion and retraction.

Portuguese paving stones (also an iconic symbol of Rio) come off easily and frequently. When they get loose, new patterns and shapes arise of their own accord, despite everything else.

In this specific case, a heart emerged for the viewer.

Three stones. Lacking. The image is only possible as a register, for the sidewalk has already been restored. Since the stones are all of the white kind, repairing them leaves no trace. It is an unexpected kindness, and to see this delicate accident as beauty and urban poetry demands awareness—attentionality. Availability for affection.

Once again, the screen depicts the image on the ground. An image of love. An intentional register of a probable non-intentionality.

City, pavement, path.

Stone and love.

***

We are united and unique in our differences and similarities. We constitute ourselves as groups in urban and cultural settlements. A culture of leaving nomadism to establish ourselves in places to which we cling to. We create self-imposed bonds, with so many conflicting feelings.

The city may be inhospitable and dirty. It may be a place of violence and exclusion, but it is also a place of affection, love, resistance, and existence in the complex and multiple humanities that seeks the detail, the delicacy, the caring—even in the imperfection.

I keep on trying to find the beauty—to affect and to let myself be affected by all the love I can find, especially on the ground.

For cities, for Rio, with love,

Paula

Epilogue

I have presented some images in order to illustrate the waves of love that may be interpreted in cities, through personal research with my own city as a means of showing how I affect and let myself be affected by it.

Over the years I have dealt with the city environment in many different aspects and scales. Being in Rio de Janeiro—in districts that varied widely in their culture, typology, safety, transportation systems, and so many other aspects of city life, that at times I am very aware of as a user of space —made me develop a curiosity about the design systems that conform to the city. The lack of a previously planned design system in many places and aspects of this city should also be considered. Here, it is possible to find the most “designed” urban solutions coexisting with the most tactical, quick, and often long-lasting, fixes from informal design sources. These instances often emerge in relation to the huge socioeconomic inequalities urban dwellers face.

My career both as an architect/urbanist and a researcher has led me to examine various approaches to the city. As a set designer for TV, one of my main responsibilities was to go outside, look attentively at the city and return to the studio grounds where I would design and build artificial scenic cities. After becoming a civil servant, I had to deal with the city under a more realistic and civic day-to-day approach.

Many times, in academic writing, researchers are asked to erase themselves from the picture, as if writing would develop exempt from personal approaches and views. On the other hand, it seems crucial to understand that one cannot detach themselves completely from their subjects, and that every text, however academic, is never liberated of the writer. Writing is an action performed by active players, and the outcome of any research can only come out through their writers.

In design research, this becomes crucial, for it is essential that researchers understand where they come from, how they relate and compare to other researchers in different fields of study, and how their research is a product that can only exist through them and their backgrounds.

So, the type of writing I have presented in this paper, however difficult to accomplish, seemed essential for me to understand better how to put myself in research, how to show myself and, at the same time, to present the results of research on design, politics, cities, policies, and city-making. It is a text that evokes the importance of everyday life, serendipity, attention, and disattention to our surroundings in the context of design research.

Thus, this is an essay on love and affection for and in cities. The theme crosses and complements another one over which I have been delving: the urban temporality of historical and cultural heritage, and the debate about the choices of pasts chosen to have a future, along with the subject of the density, sphericity, and tentacularity16 of time where ephemerality, complexity, and the small scale can have huge impacts on people’s lives.

I consider this paper a writing experiment.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Professor Zoy Anastassakis, my tutor in the doctoral research process, whose guidance I have written this text. Thanks to Professors Raquel Noronha, Barbara Szaniecki, Otavio Leonidio and my fellow colleagues and friends at the Design and Anthropology Laboratory (LaDA/ESDI) for their attentive reading and comments. I also thank Professor Frederico Coelho, PhD Raïssa de Góes and everyone who participated in the conversation circle “Tempo e Produção de Mundo” during the fifth edition of the Entremeios Seminar 2018 for the attentive listening, precise comments and incentive for publishing this article.

Endnotes

1. A person born in the city of Rio de Janeiro.↵

2. Names of districts in Rio, spread over the city.↵

3. Human is a category I will problematize throughout this essay.↵

4. Tim Ingold presents the concept of attentionality, which he opposes to intentionality. Attentionality meshes the words attention and intention as a ‘resonant coupling of concurrent movements.’ Tim Ingold, “On human correspondence,” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 23 (2016): 9.↵

5. For more information on LaDA (Laboratory of Design and Anthropology at ESDI/UERJ), please see http://ladaesdi.com.br/.↵

6. Jeanne Favret-Saada, “Ser Afetado,” Cadernos de Campo 13 (2005): 155–161.↵

7. Jane Bennett advocates for the vitality of matter, highlighting “the material agency or effectivity of nonhuman or not-quite human things,” questioning the “political theory done in the anthropocentric style.” She proposes, then, “revisions in operative notions of matter, life, self, self-interest, will, and agency.”↵

8. Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things, (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2010), viii-x.↵

9. I don’t mean to say that certain people don’t question whether they should remain in the cities or not. As a matter of fact, personal yearnings may lead individuals to desire a suburban or even rural condition.↵

10. Byung-Chul Han, Sociedade do Cansaço (The Burnout Society) (Petrópolis, RJ: Vozes, 2017), 31. (Translated from Portuguese)↵

11. I propose a working definition of the noun “disattention,” as the ability to see with the mind’s eyes, finding serendipitous messages on the ground when familiarity is established between the inhabitant and their city.↵

12. Donna Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016). Haraway presents the expression response-ability in this book, and by splitting responsibility into response-ability, I understand that Haraway brings new possibilities and implications for the being, which is moved from a place of superiority (the place where one has a presumed responsibility for his/her actions) to a more horizontal position where actions demand responses and collaboration. Turning responsibility into response-ability presumes, thus, an ability to respond.↵

13. Bruno Latour, Cogitamus: Seis Cartas sobre as Humanidades Científicas (São Paulo: Editora 34, 2016), 9. (Translated from Portuguese)↵

14. Umbanda and Candomblé are religions of African origin widely followed in Brazil. Rio de Janeiro, one of the most intense slave trading sites in the world until the 19th century, has many adaptations of these religions, which often mingle with other religions’ rites. Offerings to entities related to Umbanda and Candomblé may consist of clay dishes with various kinds of food, cigars, beverage and other items. The use of dead animals such as chickens and goats are related to Candomblé, while in Umbanda there is no animal sacrifice.↵

15. Han, Sociedade do Cansaço, 15.↵

16. Tentacular time as a time that retracts and expands, much like an octopus, being dense and, at the same time, overlapping itself. See Paula Camargo and Zoy Anastassakis, “Linear and Spheric Time: Past, Present and Future at Centro Carioca de Design, Rio de Janeiro,” International Committee of Design History and Design Studies Conference, 2018, Barcelona, Catalunya (Barcelona: Singularitats Collection, 2018), 747–751.↵

Author Affiliations

Paula de Oliveira Camargo is a PhD candidate in Design at PPDESDI-ESDI/UERJ, the Post-Graduation Program in Design at the Superior School of Industrial Design of the University of the State of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Camargo is also a fellow researcher at LaDA – Laboratory of Design and Anthropology in the same institution since 2017. She has been the director of the CCD – Centro Carioca de Design (Carioca Center for Design) in Rio de Janeiro’s Municipality since 2009.

DESIGN STUDIES BLOG

DESIGN STUDIES BLOG