Designing for Hedonic Shopping Motives: Pinterest as a Model for E-commerce Evolution

Shelby Muter

Even though the ways in which people research, shop, and purchase items have evolved, the reasons people shop have essentially stayed the same. It is widely accepted that consumers are primarily motivated by either utilitarian or hedonic goals. Utilitarian consumers are concerned with purchasing products in an efficient and timely manner; whereas hedonic consumers are focused on the potential entertainment and enjoyment that arises from the shopping experience.1 Recognizing these differences in shopping motives is especially important because of the changes in the retail environment. In 2012, U.S. retail e-commerce sales amounted to 225.5 billion U.S. dollars and are projected to grow to 434.2 billion U.S. dollars in 2017.2 With a significant increase in projected online sales, it is essential for retailers to research, evaluate, differentiate, and adapt current e-commerce design practices to capture the various needs of an expanding market.

A key component of current e-commerce design is the photography used to sell products and services. Viewing the product you would like to purchase, whether it be in-person, in a catalog or on a screen, is important to any shopping experience, but is crucial for online shoppers. For e-commerce consumers, high-quality photos are expected on retail sites, because it is the main way companies present their products and services. A National Retail Federation report shows, 67% of online customers say the quality of a product image is very important when selecting and purchasing the object, even more than the item’s description (54%) and its ratings and reviews (53%). With consumers placing considerable value on product photography, it is vital for retailers to evolve current e-commerce design methods.3

Despite prior research showing that the two primary motives for retail shopping —utilitarian and hedonic—also apply to the online shopping experience, e- commerce design has predominantly focused on fulfilling utilitarian goals.4 Designers have created simple interfaces, quick navigational tools, and easily accessible merchandise to meet these practical, task-orientated needs.5 As a result, it seems as if a standard design has been created within the industry, which treats the online presence of a company as a virtual warehouse of products. Typical e-commerce designs do not take into consideration hedonic shopping motives.

Treatment of Product Images in the E-commerce System

E-commerce design can be described and classified in many ways but the two most dominant and overarching characteristics of the current design practice are exemplified in the treatment and arrangement of product images. A quick browse through current online retail sites yields many of the same design elements and structures. Companies often choose to copy successful sites or construct a design mirroring their offline store, instead of creating virtual spaces that enhance the online shopper’s experience.6 The most popular example of

this phenomenon has been in the replication of the e-commerce giant, Amazon. Professional and amateur designers have continuously replicated elements of the Amazon.com design purely because of the site’s status as the world’s largest retailer.7 The research company, Nielsen Norman Group, warns that Amazon “is simply so different from other e-commerce sites that what’s good for Amazon is not good for normal sites.”8 The blind adoption of the Amazon-like style has resulted in well-indexed products which are extremely utilitarian but lack any sort of hedonic appeal.

Product images make up the majority of e-commerce sites and highlight a single item at multiple angles, typically on a white background. The item is usually centered within the frame of the image and includes minimal or no shadow, as if the product was floating in space. This eliminates any distractions that could result from lighting or cropping and places complete focus on the item. White backgrounds are universally used to create consistency amongst varied products and to isolate the subject. A standard e-commerce product image, intentionally static and objective in its presentation, shall be defined henceforth as a utilitarian image.

Depending on the retailer, the variety and amount of images used to show an item will vary. Some companies will only supply shoppers with a single image, while others present multiple shots of the same product. If additional shots are included, they tend to follow a standard set of angles, depending on the category of product. For instance, product images for apparel will include a model facing forwards, sideways and backwards to show the piece of clothing from different points of view. Additionally, a flat shot of the item, close-up of

“Typical e-commerce designs do not take into consideration hedonic shopping motives.”

the fabric or detail shot is sometimes included (Fig. 1). In comparison, general merchandise, such as towels or plates, tend to have less supplementary shots or are only shown in a single image.

The bulk of product images are traditionally placed on category pages, in a grid based structure and are used to document the inventory, thus allowing customers to quickly research various items. These pages normally have between

Figure 1. Various e-commerce image samples. Courtesy of Nordstrom.com

Figure 2. E-commerce grid structure. Courtesy of Jcrew.com78

three to four columns of products and extend down the length of the webpage or until the available products end. The organization of products into a three to four column structure (Fig. 2) is utilized by almost every e-commerce site, no matter what the retailer sells.

Product images are also found on individual item pages, which is where the additional images, if available, can be viewed. Individual product pages also follow a universal design in which the main image is located in the upper left corner and thumbnails are provided underneath to show any additional photos. Text descriptions are located to the right, along with sizing, color, quantity, and an “add to bag” or “add to cart” button. Customer reviews, which sometimes include user-generated photography, are found below the product images and description.

The standardized treatment and placement of e-commerce images has produced sites that have been purposefully stripped of any overbearing design or styling for the sake of ultimate usability and functionality. Researchers have cited that “organizing product information around aesthetically pleasing consumption settings or complementary product combinations, tends to lack clear organization structure which consumers need to achieve goal-oriented tasks efficiently.”9 This strategy assumes that consumers are only interested in shopping because they are focused on a goal, or in other words, only motivated from a utilitarian perspective.

The Catalog Image: Visceral Imagery, Spontaneous Discovery and Narrative Pacing

Retailers have historically used multiple and varied infrastructures and artifacts to sell products to consumers. Catalogs in particular were an integral part of the retail experience. Unlike many contemporary retail strategies, catalogs allowed for visceral imagery, narrative pacing and serendipitous discovery. There have been countless catalogs, published by varied retailers over the years but all have been primarily focused on presenting products to consumers through the use of an image.

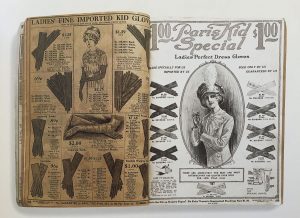

One of the first instances of catalog design was in the 1870’s, with the formation of the Montgomery Ward and Sears catalogs. The arrival of these publications was regarded as a social event, because they provided people in rural America the opportunity to view never before seen items from around the world.10 Thousands of illustrations, over hundreds of pages, were used to depict the wide array of products available to consumers (Fig. 3). Even though the product depictions in these original catalogs were illustrations placed on indexed pages, their impact on American culture was revolutionary.

Created as a natural extension of Martha Stewart Living magazine, Martha by Mail launched in 1996. Martha by Mail was a mailorder catalog (Fig. 4) designed to supply readers with all the tools, materials, and ingredients needed to create the projects found in the popular publication. The catalog originally started as an insert within Martha Stewart Living; but became so popular that by 1998 was a fully functional catalog and consumers could purchase goods online through Marthabymail.com. Readers not only loved the products but the catalog itself was highly regarded and treasured because of its beautiful design. Best described as “soft, approachable minimalism,” the catalog’s look inspired and enabled readers for years.11

Figure 3. Montgomery Ward catalog spread. From: Dianna Edwards and Robert Valentine. Catalog Design: The Art of Creating Desire. Gloucester, MA: Rockport, 2001, 11.80

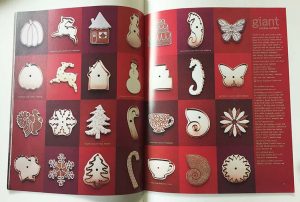

A key element to Martha by Mail’s success was the sensitivity to photography and more specifically, product styling. Each image, whether it was a full scene or individual product, was flawlessly styled. For example, instead of merely presenting an individual metal cookie cutter, full-page spreads (Fig. 5) were created showcasing beautiful decorated cookies in addition to the tool that create them. This simultaneously highlighted the product and inspired readers to decorative ideas that they could also replicate. Additionally, readers saw ideas and products they weren’t familiar with or expecting. This spontaneous discovery and exploration is a staple trait amongst catalog design.

It’s also important to note that the photography in Martha by Mail ran “the gamut, from evocative covers and romantic section openers to produce shots.”12 The different applications of imagery worked as a whole to create

Left: Figure 4. Martha by Mail cover. Courtesy of Marthamoments.blogspot.com. Right:. Figure 5. Martha by Mail spread. From: Diana Edwards and Robert Valentine. Catalog Design: The Art of Creating Desire. Gloucester, MA: Rockport, 2001, 52-53.

a story-like narrative with the context of the catalog. No matter what the conceptual idea or theme of the catalog, products were used as characters to tell the story. The combination of beautiful photographic styling, spontaneous discovery, and narrative pacing were, and continue to be, key principles to successful catalog design and, in turn, retail sales.

These images, photographed with design intent or depicted in a designed environment, can be considered hedonic images. Whereas a utilitarian image is deliberately presented to evoke no visceral response whatsoever, a hedonic image is created with the intention of evoking a visceral connection with viewers. Today, catalogs are less critical to the overall shopping experience, but the images they contain continue to provoke entertainment, desire, surprise, and wonder amongst viewers. Even though these hedonic factors remain influential in the buying behaviors of contemporary consumers, there is a void of catalog- like images within e-commerce design.

Photocentric Pinterest Model

Images, like the ones found in traditional catalogs, are scarce on online retail sites but another digital platform stepped in and has been filling the gap. The social media site, Pinterest, allows users to “pin photos into collections called boards, which serves as a big catalogs of objects.”13 Their army of 70 million users loyally pin items to more than one billion boards on the platform every month.14 These pins consist of images collected from across the Internet which means there are endless sources of image generation and consequently, varied types of photos. User-generated photos and retail produced imagery are commonly seen side by side, most of which do not fit the standard, sterile model.

In comparison to e-commerce sites, Pinterest’s design puts complete emphasis on the photography and as a result encourages serendipitous discovery. These characteristics are cornerstones of Pinterest’s success but also have historical connections and roots in the traditional catalog designs that were previously mentioned. Users’ extensive and unwavering participation in the platform implies a strong desire for an online shopping experience that is centered around imagery and serendipitous discovery.

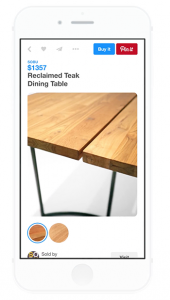

Pinterest is the top traffic source to retailer’s websites, which suggests that consumers are consistently utilizing the image centric platform during their online shopping process.15 Instead of visiting retail sites for item discovery or inspiration, contemporary shoppers are using Pinterest as their initial research tool. Once consumers find the product they want, they visit the retail site or another distributor to purchase the item. This process could drastically change because Pinterest has taken notice of its users’ behavior and has recently launched buyable pins. Currently only available on iPads and iPhones, this feature allows consumers to directly purchase items from Pinterest (Fig 6.). This makes it extremely easy for consumers “to realize their digitally expressed aspirations in the physical world with no more than a few taps on a smartphone.”16

Pinterest’s main appeal is the vast array of interesting imagery available for users to view, organize, or even purchase. Although there are some traditional product images on Pinterest, the majority are drastically different than the photos seen

Left: Figure 6. Pinterest iPhone application. Courtesy of Pinterest.

Right: Figure 7. Example of Pinterest board. Courtesy of Pinterest.

on typical retail sites since they are user-generated. For instance, a search for leather jackets yields seemingly endless images, most of which show realwomen, not models or manikins, in a designed environment (Fig. 7). In comparison to typical e-commerce photos, these images are visually interesting and impactful because they contain personality, style, and emotion.

Another important characteristic of the photos on Pinterest is that most have an authenticity which is lacking from the majority of retail imagery. Many images on Pinterest are not overly edited, photoshopped, or even manipulated at all. This is important because unlike brand-perfect retail images, consumers are able to see the products as they actually are. Displaying user-generated imagery has even been utilized by many travel websites. Tripadvisor.com allows users the option to view management photos seperately to travelers’ photos. This is especially helpful because users can see how the establishment looks from a previous traveler who has no ulterior motive. User-generated photos offer an honest portrayal of the product or service the consumer is interested in purchasing. Many retail sites also allow customers to post their own images in the user reviews section of an individual product page. In this case the images are used as additional information and are not displayed or presented alongside the brand-generated photography.

A key feature of the Pinterest site is the ability to create collections of images through the use of boards. Boards allow users and brands to easily organize the images they have generated or found in one place. When designing a board, creators are asked to provide a title and select an organizational category. Boards

“User-generated photos offer an honest portrayal of the product or service the consumer is interested in purchasing.” tend to have themes, topics, or an overarching focus under which all the images fall. This process of collecting, organizing, and curating images is reminiscent of catalog design because the content is related. Both historical and contemporary catalogs have traditionally provided viewers with monthly, seasonal, or thematic collections of images, which have been carefully organized depending on the chosen topic. Many retailers are recreating the catalog experience through the creation of Pinterest boards. For example, the women’s clothing company, Madewell, has a Pinterest account which currently includes ninety-five different boards. Some of these boards are seasonal such as the “Rome / Fall 2015 Catalog” while other are specific to a particular fabric or garment. Additionally, Madewell has created boards that do not show their products but instead highlight images depicting topics such as travel, art, and typography. The use of boards by retail companies on Pinterest is recognition that the hedonic image helps to not only sell products but adds brand value.

For hedonic shoppers, having fun is most important and one of the ways to achieve the enjoyable moments of shopping is through serendipity. This means that consumers find an item or product that they did not originally know they wanted, but upon discovery, are interested or intrigued by the item. The experience of serendipitous or spontaneous discovery is widely associated with window-browsing or catalog shopping because consumers are usually unaware of the available products until they participate in the experience. Similarly, Pinterest’s goal is to become the “number one destination for discovering things, an alternative to search.”17 Instead of helping users find specific information, like Google does, Pinterest wants to help users find things they did not know they wanted or needed. Replicating serendipitous discovery within the context of e-commerce has generally not occurred or been discussed because the images that are typically associated with this experience are absent from the digital environment.

Retail Images in Consumer Society

Images play many and varied roles depending upon the society, industry, and context in which they are used; but, for “consumer societies dependent upon the constant production and consumption of goods in order to function,” images are a central component.18 Cultural ideas regarding beauty, self-image, and lifestyle are constructed through images, most notably those found in advertisements. A key strategy of both historical and contemporary retail images is to encourage the consumer to envision his or herself within the photo. Sturken and Cartwright describe this process as abstraction, in which the consumers imagine themselves in the situation portrayed, as well as in the future with the products or goods they could have. Meredith Davis in Graphic Design Theory points to the cultural theory of Jean Baudrillard when discussing codes in design and photography.19 According to Baudrillard, furniture catalogs and other advertisements with similar imagery encourage us to consume by presenting scenes that are complete only when we purchase all the matching components of the system. The value of an Figure 8. Spread from IKEA’s Spring 2016 catalog, Courtesy of IKEA.

86

PLOTS | VOLUME 3 | 2016

individual object is found within the larger system. For instance, the global furniture retailer, IKEA (Fig. 8), is one of the few contemporary companies still creating and publishing catalogs. The images in these catalogs portray various kitchen, dinning room, living room and bedroom scenes that are all perfectly arranged with furniture, lights, and other products from IKEA. Each item is strategically placed within the image frame, creating a complete system of products. The “system” images such as the ones used by IKEA have been historically and repeatedly shown in catalogs; but, are almost entirely absent from the online shopping environment. This absence reinforces the homogenous website designs and imagery which seem to be based on the Amazon model. This is particularly interesting given the success of “system” images in influencing consumer behavior and constructing cultural ideals.

The evolution of technology and as a result, e- commerce, has left consumers with sterile images. These photos are nearly the exact opposite of the “system” images predominantly discussed and analyzed by theorists. Since current e-commerce product images are designed for utilitarian, goal-oriented tasks, they purposefully lack scenes and environments. As a result, this challenges consumers to envision themselves in the product or item portrayed. It also makes it difficult for shoppers to love and connect to the image. Roland Barthes explains his theory of photography in the short book Camera Lucida, describing the studium of a photograph as culturally determined and “ultimately always coded.”20 The studium can be summarized as a vague interest in the image and one that is simply “all right.”21 Barthes also proposes the punctum to describe a much more “intense and personal reaction” to an image inspired by a certain detail.22 This detail which evokes the excitement or interest is missing from modern e-commerce imagery. Previous research has isolated both hedonic and utilitarian indicators of consumer satisfaction within e-commerce websites.23 However, this research has not truly allowed for an exploration of hedonic factors because they are very difficult to test and are extremely subjective. Historically, basic utilitarian features such as usability, functionality and reliability have not always been elemental to e-commerce design, therefore testing usability has been given primary importance. With the evolution of technology and the expansion of online shopping, this mentality should be reconsidered. Usability and functionality are now expected features of any successful e- commerce experience and the value added by contemporary imagery must not be discounted or disregarded. The growth and success of the photocentric Pinterest model is reflective of this change.

Endnotes

- Terry L. Childers et al., “Hedonic and Utilitarian Motivations for Online Retail Shopping Behavior,”

Journal of Retailing 77:4 (2001): 51135.

- Statista, “U.S. Retail E-

commerce Sales 2010-2018,”

http://www.statista.com/statistics/272391/

usretailecommercesalesforecast.

- Jeff Bullas, “6 Powerful Reasons Why You Should include Images in Your Marketing,” http://

www.jeffbullas.com/2012/05/28/6-powerful-reasons-why-you-should-include-images-in-your-marketing-

infographic/.

- M. Wolfinbarger and M.C. Gilly, “Shopping Online for Freedom, Control, and Fun,” California

Management Review (2001): 3455.

- Jakob Nielsen, “LowEnd

Media for User Empowerment,” Nielsen Norman Group, https://www.

nngroup.com/articles/low-end-media-for-user-empowerment/.

- Angela V. Hausman and Jeffrey Sam Siekpe, “The Effect of Web Interface Features on Consumer

Online Purchase Intentions,” Journal of Business Research 62:1 (2009): 513.

- Shannon Pettypiece, “Amazon Passes WalMart

as Biggest Retailer by Market Value,” Bloomberg

Business, http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-07-23/amazon-surpasses-wal-mart-as-biggest-

retailer-by-market-value.

- Jakob Nielsen, “Amazon: No Longer the Role Model for ECommerce

Design,” Nielsen Norman

Group, July 25, 2005, https://www.nngroup.com/articles/amazon-no-e-commerce-role-model/.

- C. Mathwick, N. Malhotrab and E. Rigdon, “The Effect of Dynamic Retail Experiences on Experiential

Perceptions of Value: An Internet and Catalog Comparison,” Journal of Retailing (2002): 51–60.

- Dianna Edwards and Robert Valentine, Catalog Design: The Art of Creating Desire (Gloucester, MA:

Rockport, 2001), 10.

- Edwards and Valentine, “Catalog Design,” 54.

88

PLOTS | VOLUME 3 | 2016

- Ibid., 58.

- Alexis C Madrigal, “What Is Pinterest? A Database of Intentions,” The Atlantic, July 31, 2014,

http://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2014/07/what-is-pinterest-a-database-of-intentions/

375365/.

- Davey Alba, “Pinterest’s Quest to Make a Buy Button You’d Actually Click,” Wired, June 24, 2015,

http://www.wired.com/2015/06/pinterests-quest-make-buy-button-youd-actually-click/.

- Evigo, “Experian: Pinterest is the Top Social Media Traffic Driver for Retailer Websites,” January 4,

2014, https://evigo.com/12804-experian-pinterest-top-social-media-traffic-driver-retailer-websites/.

- Davey, “Pinterest’s Quest to Make a Buy Button You’d Actually Click.”

- Ibid.

- Marita Sturken and Lisa Cartwright, Practices of Looking: An Introduction to Visual Culture (Oxford:

Oxford University Press, 2001), 189.

- Meredith Davis, Graphic Design Theory (London: Thames & Hudson, 2012), 23-25.

- Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography (New York: Hill and Wang, 1981), 51.

- Barthes, Camera Lucida.

- Andy Grundberg, “Death in the Photography,” The New York Times, August 23, 1981, http://www.

nytimes.com/1981/08/23/books/death-in-the-photograph.html?pagewanted=all.

- M. Wolfinbarger and M.C. Gilly, “Shopping Online for Freedom, Control, and Fun,” California

Management Review (2001): 3455.

Author Affiliations

Shelby Muter

MFA School of Visual Communication Design, Kent State University.

DESIGN STUDIES BLOG

DESIGN STUDIES BLOG