Caroline is Assistant Professor in the History & Theory of Design practice and Curatorial Studies at Parsons ADHT. She was most recently a Research and Teaching Associate (Scientist) and Research Coordinator at ALICE laboratory, Institute of Architecture, at the Swiss federal institute of technology in Lausanne (EPFL), Switzerland, where she taught in the master’s and doctoral programs. She holds a PhD in the History & Theory of Architecture from McGill University, Montreal. In 2014 she was a Visiting Scholar at the Canadian Centre for Architecture in Montreal. Her publications tend to cross disciplinary limits, moving from architectural theory and criticism to language theories, from questions of urban social space to contemporary arts and design practices.

Caroline is Assistant Professor in the History & Theory of Design practice and Curatorial Studies at Parsons ADHT. She was most recently a Research and Teaching Associate (Scientist) and Research Coordinator at ALICE laboratory, Institute of Architecture, at the Swiss federal institute of technology in Lausanne (EPFL), Switzerland, where she taught in the master’s and doctoral programs. She holds a PhD in the History & Theory of Architecture from McGill University, Montreal. In 2014 she was a Visiting Scholar at the Canadian Centre for Architecture in Montreal. Her publications tend to cross disciplinary limits, moving from architectural theory and criticism to language theories, from questions of urban social space to contemporary arts and design practices.

Has it ever happened: being the only student to show up for a class? Imagine the benefit. It might feel like the following conversation Parsons ADHT’s Casey Haymes had while sitting with Parsons ADHT faculty Caroline Dionne.

Casey: Did you choose The New School because of New York or choose New York because of The New School?

Caroline: I have always said that if I could choose a place to live it would be New York. So, after completing my post-doctoral contract at the École polytechnique fédérale Lausanne (Switzerland), I applied to a variety of positions in larger cities. New York and The New School were my first choices. I arrived in August, 2016 and started teaching a few weeks later.

Do you think in French? Dream in English? If you were planning to write an essay, which language would you choose?

I am bilingual in my thinking and dreams, but French is my first language. I always write in the language of the final product. In my masters and PhD studies, I wrote in English directly. When I completed my PhD, I moved to Switzerland and worked for a few years in a francophone architectural, engineering, and new technologies journal. It was published biweekly, so not only did I go back to writing in my native tongue, I had to learn to write very fast. I might write better in French but English is more playful for me. Sometimes, in English, I come up with weird formulations that are possibly unorthodox but they access my subterranean thoughts, how I see things in my head. The freedom I take in using English yields something productive.

I am intrigued by your research on Lewis Carroll and the connections you make between spatial perception and language. [How] did your author choice affect the language, the choice of spaces and the perception of them?

For my PhD I focused on Lewis Carroll’s fiction, his books for children, and his scientific writing; he was a mathematician, geometrician, and logician, so he wrote books defending Euclidean geometry. And he also wrote books, articles, and essays on symbolic logic. I investigated his specific way of playing with language. His work is often referred to as a literature of nonsense. I’m not using nonsense in the sense of an absence of meaning but more as a surplus of meaning, of bringing together different, or opposite, significations. Like how a paradox sometimes works: this is this but it is also that. Nonsense is this rich proliferation of coexisting antagonistic meanings that provoke laughter and make your mind spin. I was interested in finding an analogy between–or encounter with–architecture, the way we experience spaces and this sort of movement of the mind that is induced by reading Carroll’s work. This was my first intuition about his work. After a while, I discovered his interest in scientific–one could say philosophical–questions of logic, questions of working on an elevated level of linguistics, trying to understand his own practice as a writer in relation to science through language. There’s a series of pamphlets he wrote–and two of those were directly concerned with architecture–for a project being constructed at Oxford, where he was teaching. This provided an opportunity to look at ways of understanding how architecture might become meaningful in relation to a literary practice.

Now, in my research, I’m very interested in how designers can involve in the process those who will be directly concerned with the design production. So I’m looking at what I call “collective design practices” and looking in the context of what is usually referred to as the participatory design movement, which is a tendency worldwide to account for the ways in which our everyday interactions with objects, things, and spaces are actually contributing to the production of these objects.

Does this function as a response to capitalism?

Designers often study use–or usage–to adapt their production to the market. You can use a bird’s eye view to understand the modern city. The way it is seen from above has a certain order, or structure, but you can also understand the city through the everyday interactions of its inhabitants–the citizens–and reach a completely different understanding of the space of a given place through the very ordinary daily activities it fosters.

My primary field is architecture, so that’s the lens I use. But the ways of doing and interacting for citizens produce spaces that are qualitatively different from the sort of geometric, mathematical understanding of spaces and objects. As designers we’ve inherited this very linear mode of production where you meet a client, have a briefing, you design, you make a proposal, and you get the project built. Then it’s out there, and users function as the very end of the process. I’m interested in looking at how this can be challenged and if, as designers, we relinquish a little bit of our authorship and acknowledge that we’re also citizens and we’re also parts of groups that can claim and transform space from within and can intervene in the design process, then this sort of authoritarian attitude that we’ve inherited from 20th century modernism might be challenged. I find it’s very important to design ways around the investment in a certain end or outcome that dictates the means. What I’m interested in looking at are processes of design that are more inclusive, that will involve different types of actors, not just end users for statistics of inhabitants but different types of people involved in a design process.

Photo credit: Casey Haymes

Let’s imagine a design group that includes a designer, politician, client, cleaning and maintenance employees. The idea with this approach to design is that it’s not enough to just simply say, let’s bring all these people around the table in the room and do the project together; if you don’t break up this hierarchy of who’s in charge, who is the specialist and who is just invited as a participant to be fed information–if you don’t challenge this dynamic, you’re not really talking about participation or a collaborative design process. To do that you have to recognize that the people who have been living in a given neighborhood or on a street or in a building, or the people who are in charge of the maintenance, or the people who will actually be sitting at their desk in a space that you design, actually come in with years of architectural and spatial experience, years of an embedded, latent knowledge of a given place, and that this knowledge of a place and a time can be shared. This requires processes of narration. You have to create a context in which all of the citizens can tell the stories that have marked their lives in different parts of New York.

(As if I’m suddenly an expert, I’ll say) it’s also important to create a context in which attention is paid to who’s hearing the citizens included in this process, rather than just who’s speaking or making claims. To explore the distribution of agency.

Not only should the designer step down a little and account for this knowledge that comes from potential end users, citizens, and inhabitants, but designers can become learners and not just authoritative specialists. They have to learn to listen, learn to frame their intentions for a given project into a compelling narrative where everyone will feel concerned, implicated, and involved. Design is something that proposes a different future. So there’s a lot of storytelling going on: what happened in the past, what people know about the given place, or their day-to-day activity. This design process is not just about bringing people together to express their needs, and then you as a specialist catering to those needs; it’s really seeing the other, this person that you bring into a process, as someone who possesses valid knowledge, and that this knowledge–bringing together these different levels of skills, knowledge, and understanding of a project–will make it better.

I imagine that the people who are receiving and processing this information should be diversified, to prevent biases from obscuring perception.

Let’s say you’re trying to rethink design processes as grounded and language based (e.g., speeches) then you have to account for the inherent ways in which language works.The premise at the heart of the way we communicate is misunderstanding. So between what I think and what I’m trying to say there’s always a gap, and you’re asking me to clarify. In this exchange my thoughts get clarified. My own understanding of where I stand is forged through misunderstanding.

If we think of design processes in that way we have to make a little bit more time to account for this very vivid, very problematic aspect of communication, and not really be in a problem solving mindset looking for potential solutions, choosing A, B or C, and then proceeding. It has to be much more fluid, more open-end, where you make mistakes. You account for them, you come back, assess, share an understanding, and then you move on. This may sound simplistic, but biases are part of what makes us human. They do condition a lot of our interactions. Acknowledging our biases, not just as designers but as members of a group, a society, is key if we want to engage in any kind of dialogue.

Is this approach to a design practice common?

It’s been growing since the late ’60s, both in Europe and in North America. This is the focus of my research right now. By examining different case studies, I’m trying to pin down what makes some of these endeavors successful and to propose concepts and theories that might allow other designers, teachers, or students to understand these questions of a more language-driven design process that is more collective and collaborative.

This doesn’t sound very amenable to our current market liberal economy. How does neoliberal capitalism absorb this?

This iterative and more experimental approach to design can actually save money. Or at the very least it can lead to the development of a more responsive proposal. In the case of architectural or urban projects for instance, in the long run you end up involving a community into caring about a given space or place. You end up fostering a sense of ownership, which can have very direct repercussions on the quality and sustainability of a physical environment. A lot of the outcome depends on how you conduct the process of making this designed thing, this building, this product. There’s a strong tradition of user experience development in systems design and web design that we can find inspiration from.

Any theorists you have read and reread? Whose books you have given signature by marking up? Any quotes you’d like to share from your fridge?

I don’t like name dropping but these days I’ve been working on a series of articles or essays where I’m attempting to synthesize the work of the French philosopher Paul Ricœur. Because he was associated with tradition and the establishment, he was disregarded in France during and after the student movements of 1968. In recent years there’s a renewed interest in his work. I find his book The Course of Recognition to be particularly spectacular. In it, he carefully analyzes semantic twists of the term recognition, investigating several levels, or voices, to the word. Take the notion of its active voice: I recognize someone. I recognize you because I saw you on the internet. This is seeing how one thing corresponds to an image of itself. And consider the passive voice: to be recognized by your peers for what you’re capable of. Recognition also means to re-cognate, to know anew, so in our interactions with others we can find something about ourselves that we already know. I find that concept vital to the design processes I’m interested in. Ricœur really highlights in this book that there are several levels of recognition that govern our interactions with people and things in the production of knowledge and how language participates in that process. And it’s fascinating to see. He’s also very interested in the political and ethical dimensions of these questions. For instance, we often put a lot of energy into doing something for the very simple, yet crucial, possibility of being recognized by others as having capabilities, that is, for what we’re able to do.

Ricœur traces it all back to the Greek myths and this notion of fame and recognition of the deeds of great men. In the modern context, he argues, this completely changes. But the fact that something persists of that value of recognition, Ricœur ties it to the pure generosity of a gift, to being able to give something without expecting anything in return.

Does he believe pure gifts actually exist?

According to him they’re extremely rare, and they define who we are as people.

Regarding who we are as New Yorkers, I was riding the G train yesterday and a woman warned passengers against valuing things over love. She then sang “Lean on Me” and, without asking for anything, exited at the next stop.

New York is hectic and overwhelming, but it’s also a place where there’s less judgment. And there’s the possibility for anonymity. I really enjoy how if you act wild people won’t judge, but if you’re in distress people are extremely kind. There’s a lot help waiting around you.

Do you have a favorite architectural space at The New School (or in New York) yet? A space that unites language and design?

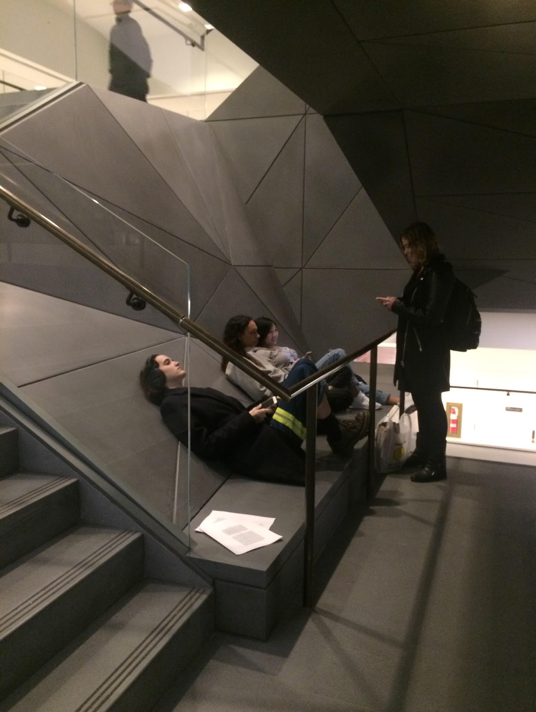

What I really care about is what spaces allow us to do. The basic physical presence of architecture and the way it might look for me has to be combined with a set of spatial conditions that make it possible for things that are socially positive to happen. The New School’s University Center building is interesting because it reveals gaps between the intention of a designer and the day-to-day use. This notion that the staircase becomes this live-work-talk space throughout the building is great but ultimately it’s not meeting its full potential. A lot of great little corners are rendered inaccessible for security reasons, or dictated by a rather strict building code. So it’s didactic in the way that it shows the problems but also with how students will sneak into spaces and appropriate them. I see a lot of students entering the folds of the staircase, and that’s when it becomes interesting.

Photo credit: Caroline Dionne

There’s also something happening in the verticality of The New School campus, and the way that–although we might hate those elevators because they slow us down–we end up meeting people in those contexts we would not be talking to otherwise. So I see the benefit of the constraints.

Photo credit: Casey Haymes

Also, the University Center’s spiraling staircase and residence hall bring a centrality that was perhaps missing for The New School.

Photo credit: Casey Haymes

I think Manhattan as a piece of architecture is one of the most amazing spaces in the world. It’s not just one building; it’s also what goes on in between those buildings and what you can discover sometimes when you’re granted access to spaces like the inner courtyards.

Photo credit: Casey Haymes

Like the Vera List Courtyard between the 11th and 12th Street buildings.

I really enjoy the commute on the Q train, seeing the island as I enter and exit Manhattan from Brooklyn. I can’t get enough of that view. But that’s the postcard, the distant view. What I find fascinating about places like New York is, even though you can have an understanding of the limits of the island, it escapes your understanding when you’re in it. This chaotic meandering causes a feeling of infinite possibilities.

Any advice for students entering or leaving the ADHT MA programs?

Sometimes students ask me, How do I go about thinking of academia as a career or a field in which I can survive? What I usually tell them is that they’re in an amazing school, pursuing specific and rigorous and rich MA programs. They’re going to acquire skills, open-mindedness and knowledge throughout the learning process. In addition to the knowledge acquisition, skill development, and learning to speak up and voice ideas, what is crucial is for students to realize what they don’t know. And to continue to investigate the scope of knowledge out there that remains possible. That’s the beauty of higher education, realizing what you don’t know. And you’ll never be bored because there are always new questions to formulate and new ideas to try to express.

It’s not only about what you know when you graduate, but realizing what’s out there and how your relationships with others change throughout the learning process. And seeing human beings through all wakes of life and from such different backgrounds as having something to contribute.

How can you understand what you do know without understanding what you don’t know?

Exactly. Knowledge is unstable and always in the making. A practice. For me the process is more important and interesting than the final product.

Photo credit: Casey Haymes