Susan Yelavich, Associate Professor and Director of the MA Design Studies program, returns this fall after a year-long sabbatical. We catch up with Professor Yelavich as she pauses in writing her new book, Reading Design, and looks toward some exciting developments for the new academic year.

What have you been up to during your leave?

I spent the summer of 2015 laying the groundwork for my book on design and literature, tentatively titled Reading Design. Then put the project on the back burner briefly to honor commitments I’d made to lecture about design and leisure at the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts’ FAIR Design conference in Warsaw and at Centro design school in Mexico City. I also spoke about my new book at Wesleyan University. Each of these talks, as you might expect, was contextualized within the field of design studies, which looks at the consequences and the potential for design.

Design Studies is crucial because it reflects on the impact of design practices that otherwise might forge ahead without much analysis. Many designers are so busy working that they have little time to reflect and consider their work with regard to other modes of thought and action. Which is crazy since design affects so many different aspects of life. Of course there are always exceptions; architects and urbanists can be prolific critics and writers, and I know a number of graphic and product designers who contribute to the literature about design. But in general, there is a dearth of attention to the essential nature of design.

There is an NPR ad I love that goes something like, “It’s easy to find out what’s going on, but we tell you why.” In Design Studies, we try to do the same and look at the conditions and contexts that are engendered by things, places, and systems. For example, right now I am looking at a tour bus outside my window. Considering that tour bus from a design perspective, we could situate it in the systems that support tourism and travel; we could also analyze the bus as a means of marketing and consumption, given that it’s slathered with ads. Equally we could view it in light of traffic issues in the city, or the materials the tour bus is made of, or the fuel it uses and its environmental effects, and so on. The fact that the tour bus is not mono-functional is probably self-evident to many people, however the multi-faceted nature of things is rarely discussed under the rubric of design outside of the academy. We tend to have tunnel vision.

What do you think the benefits are of exploring beyond an object’s mono-functionality?

Let me give you an example: For many years it was tacit knowledge that many cultures tolerated, if not the outright abuse of women, then the treatment of women as indentured servants. Today, by virtue of mass media’s images of women holding jobs, teaching school, and running countries, that knowledge is no longer tacit. There’s no way that one can ignore that there other ideas about the role of women in society. Even those who firmly believe that women are chattel to be used and bartered know this is so. (In fact, this is why we witness so many kidnapping of girls from schools by radical fundamentalists). My example, of course, is about a social framework not an object. But consider an object that represents such repression, or better a missing object, such as a driver’s license in countries that forbid them to women. That license is more than just a piece of paper that legally lets one start a car; it is also a tool of dominance.

The point is that we are exposed to so much now that we have an ethical responsibility to use that knowledge to make more informed decisions. In fact, we have exponentially more information than we had a generation ago. So it takes some time to sort out the variables that could be considered, might not be considered now, and those we must consider when examining an issue involving the material world–and what issue doesn’t? This is why the purview of Design Studies may seem awfully broad. But the reality is that, once you look at an object—like that tour bus I just saw outside my window—and start connecting the dots, there is no escaping the almost limitless impact of design. The challenge is to pick our battles, so to speak, to winnow down the possibilities that can be dealt with intelligently, and to create cogent narratives that draw attention to the causes, effects, and possibilities of our increasingly fabricated existence, the artificial worlds we are designing.

What are some publications and/or scholars worth noting that help highlight the context surrounding design?

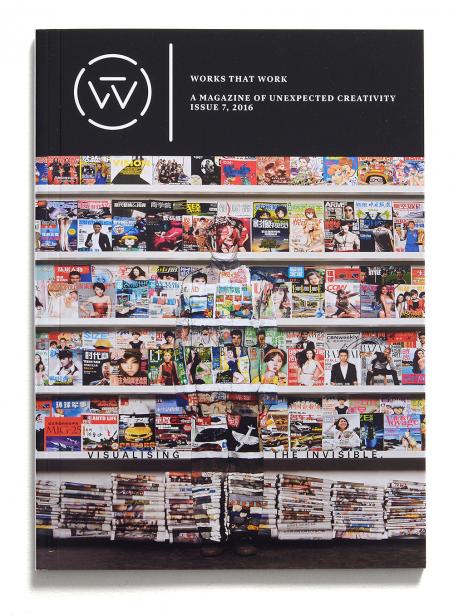

One of my favorites is an article called “Shoe Dreams” that John Seabrook wrote for the New Yorker some years ago on Diego Della Valle, the CEO and founder of Tod’s. In that story you find out that the inspiration for Tod’s moccasins—those aristocratic soft leather shoes–came from Gianni Agnelli (1921-2003). Agnelli, who ran FIAT, wore them to the races, and that several fashions in Italy were inspired by him (like wearing your wristwatch over the cuff of your shirt). So all of a sudden this shoe, which looks very Anglophile—and it happens to be that many Italians really admire English fashion—is not just a shoe anymore, it’s an Italian cultural icon. And not even a simple one because I’ve already just thrown England into the mix. I could cite countless others from canonical works such as Roland Barthes Mythologies, to books by design philosophers like Peter-Paul Verbeek’s What Things Do, to Works that Work produced in The Hague by designer Peter Bil’ak. My point is that design needs more than just reportage, because it shapes our identities, our bodies, our politics, our environment, and our social relations profoundly—and many times silently.

Sadly, the reality is that most publications (print and otherwise) are hampered by their economic model, which reduces the possibilities for critical and extended coverage. I know there’s a balance to be had; there are times when the more effective means of communication is one of brevity. However, I worry that this format (be it a tweet or a blog post) is becoming the only way to reach a general readership, even a general design readership. Hence the need for design studies, fashion studies, and the study of the history of design and curation—all encompassed in the MA programs of Parsons School of Art and Design History and Theory.

Excellent, thank you for the recommendations! How does your book use literary works to illuminate questions of design and context?

My current book Reading Design uses literature to learn about the social life (or lives) of design. It reveals what novels and poetry can tell us about places and things once they leave the proverbial studio and enter our daily lives. Of course, it’s important to read philosophy, sociology, anthropology, and psychology for other insights into the workings of design. And it goes without saying that it’s important to read the works of design studies scholars. But I think you can often get a more visceral understanding of design through stories, whether it’s stories that people tell in oral histories or those of writers like Marcel Proust.

I especially like the passage in Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past where he describes making his first phone call to his grandmother (remember, the phone was brand new in the 1920s). When he’s finally connected, he comes to the recognition—actually the shock—that he’s holding her voice and only her voice in his ear. From this we can extrapolate that technology changes not only the way we use our senses (in that case, isolating the sense of hearing), but it also changes our behavior. To wit, he speaks more sweetly to her when he can’t see her face. You know, he can’t see her grimacing. If you’re a cynic you’re going to say, “Well, he’s homesick, of course he talks to her more sweetly.” But it’s more powerful than that because he goes on to describe how he feels when the telephone cuts him off. (This was in the days of phone operators and routinely dropped calls.) The abrupt break in his conversation reminds him that he will eventually be fatally cut off from his grandmother after her death. Technology, which is supposed to transcend time and space, is fallible. It’s as fallible as we are. This is just one of many stories—in fiction, poetry, literary non-fiction—which tacitly make the case that design is far more than just a finite solution for something that needs fixing, that it is far more than a set of extraneous flourishes.

This isn’t to say that design isn’t about style. I think design is always on some level about aesthetics and style, but that begs the question, “what is style?” Orhan Pamuk talks about style in the East and in the West as a visual mode of communication. For instance, the style of Turkish miniature paintings from the 1500s communicates a communal ethos; no one person is thought to be more important than another, except perhaps the Sultan and even his features are rendered generally. Whereas a contemporary Renaissance painting in which the figures are identifiable, reflects a western value system in which individualism is important. So there is meaning in style; in Pamuk’s novel meaning is simultaneously aesthetic, political, and social. Understanding why things look the way they do is truly fascinating, as well as essential in making appropriate design choices.

Are there any pieces of literature that you came across in your research for Reading Design that you’d like to highlight?

Since there are eight chapters in the book (Culture, Politics, Mythology, Technology, Domesticity, the Senses, Consumption, and Mortality) covering approximately fifty works of literature, this is a hard question. But in the interest of brevity, I’ll restrict myself to a few short pieces. The first that comes to mind is “Housekeeping Observation” by Lydia Davis from her book Can’t and Won’t:

Under all this dirt

The floor is really very clean.

Her marvelously succinct observation raises questions such as: what is a floor? what’s dirty, what’s clean? who is responsible? There are a lot of implications to be considered here that beg to be teased out.

I am also especially fond of Wisława Szymborska’s poem “Museum.” This excerpt from it appears in my introduction:

The crown has outlasted the head.

The hand has lost out to the glove.

The right shoe has defeated the foot.

So here we find another dimension of things. Unlike Proust’s telephone which is a mortal instrument, Symborska’s things survive us. Part of the reason why people design is to extend ourselves: to make us more powerful, to shape the future, or in some cases to achieve a kind immortality. I think it’s moving to consider design from this perspective. You know, when you go to a museum you rarely think of the head because you only see the crown. Symborska reminds us that things have a very particular relation to the human body.

What are you looking forward to upon your return?

I’m really looking forward to finding ways in which students can be integrally involved in the annual symposium of the MA Design Studies program. The symposium is a chance for us to introduce Design Studies to the larger academic community of The New School and to the design community at large, particularly because it is less understood in the U.S. than in say places like Britain and Scandinavia where it’s been around for decades now.

I am also really looking forward to teaching the Spring 2017 course The Palace of Culture: An Exploration in Design, Humanities, and Social Sciences, which entails two seminars in New York and an intensive week of classes in Warsaw, Poland. In this course, we will have an opportunity to see first-hand how a single building on a fraught site can be examined as an opportunity to consider how we might deal with painful memories—be they of war, persecution, disaster, or other forms of collective civic loss. The Palace of Culture course will be offered in conjunction with the Parsons exhibition Far Away From Where that opens next February. The course will be open to MA and MFA students as well as seniors by special permission, and will be taught by myself with Malgo Bakalarz (PhD candidate in sociology at the New School) and Mateusz Halawa (also a PhD candidate at NSSR), who is currently teaching at the School of Form Poznan, Poland. And most exciting is the fact that our students will work with their Polish counterparts from the School of Form in both discussing the nature of building and memory and prototyping alternatives.

Last but not least, I’ll be expanding the ways in which our MA Design Studies students can explore their theories in both words and practice. More to come on that!