Launched by ADHT’s Insights Magazine, Notices is a multi-part series which features essays, reviews, and commentaries produced by students currently enrolled in one or more of the school’s ongoing semester courses. Migrating images, ideas, and conversations in and out of the Parsons community everyday, students offer a way of seeing and engaging with multiple worlds at the same time. Their education–rather than being limited to the classroom–is diffusive and fluid, their curiosity, roaming and magnetic.

The latest installment features an essay by Rikki Byrd, a first year graduate student in the Fashion Studies Masters of Arts Program.

Black the Color We Wear: The Temporality of Blackness in Fashion

by Rikki Byrd

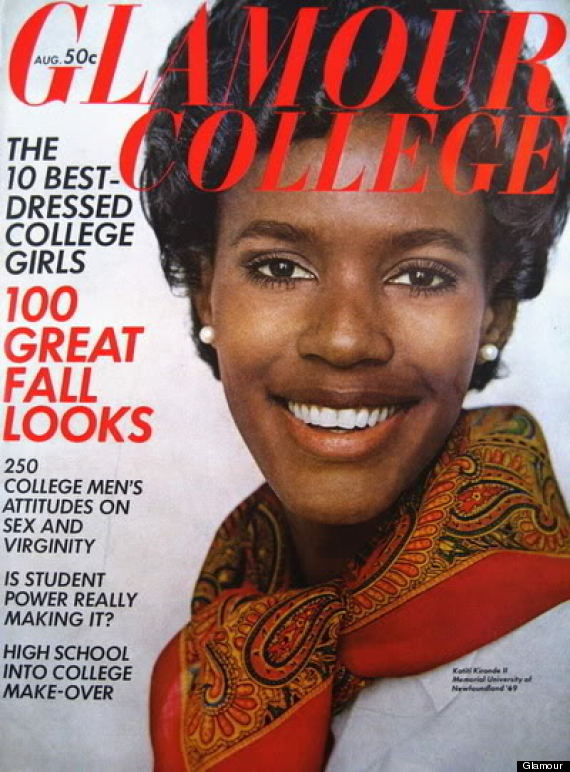

Katiti Kironde, the first black model to appear on Glamour’s cover. 1968. Photo: Glamour

On April 11, 1969 a fashion supplement appeared in TIME Magazine. In it, an article titled “Black Look in Beauty” considered a trend of blackness in the fashion industry. The article reads that the fashion industry “has started thinking black.” It goes on to highlight the most coming-of-age black models during this time, such as Donyale Luna, Naomi Sims, Charlene Dash, Jolie Jones, Anne Fowler and Yahne Sangare, who were appearing in some of fashion’s most elite publications that before this time, were not featuring black models at all. This arrival of black models and the use of their blackness was assigned to what TIME wrote as “the temper of the times.” The article quotes photographer Bert Stern, who said that, “Negroes photograph better against white.” Unmatched fashion publicist Eleanor Lambert told the publication “this is the moment for the Negro girl. She has long legs, apt to be very thin and wiry. This is the look of now” (TIME Magazine 1969).

Lambert’s use of the word “now” holds true the implication that whom she states as the Negro girl is temporal–going in and out of style like many other trends in fashion. Sociologists have written about the short-lived trends in fashion: Werner Sombart writes about the “tempo of changes in fashion,” and if any “fashion” spans several years it brings into question whether or not it has become a national costume (2004, 313); Georg Simmel discusses fashion in terms of the distinction between its “simultaneous beginning and end,” writing that “fashion includes…the charm of novelty coupled to that of transitoriness” (2004, 295); Yuniya Kawamura boldly writes that, “the essence of fashion is change ” (2005). These concepts of temporality specifically focus on modes of dress and style in fashion, as it pertains to consumption and class. However, I wish to elucidate the temporality of blackness in fashion, as it functions as a trend, or in what Lambert states as “the look of now.”

In Skin Deep (Summers 1998, PXIII), former Ford Model and fashion scholar Barbara Summers writes: “It is ridiculous to think that skin color could ever be in or out of style.” Other writers on blackness and fashion have written about how slaves came to fashion themselves (Miller 2009), black women’s fashion and beauty magazines and advertisements (Rooks 2004), and the permanence of African culture through fashion (Griebel 1995). To consider race and fashion is to consider how the former is reconstructed into an aesthetic statement. Much like a resort collection that is temporal in that it is meant for warmer weather and months, or coats and boots from a fall/winter collection, blackness is also used as a means of display and consumption. The evolution of blackness can be studied as fashionable—from slavery to more recent examples such as the lack of diversity at New York Fashion Week.

On Display

In 1973, four years after the TIME’s article, Eleanor Lambert coordinated one of fashion’s most revolutionizing runway shows. In an effort to raise funds for Louis XIV’s Palace of Versailles in France, a fashion show was organized pitting French designers against American designers. Lambert worked with modeling agencies to hire models for American designers–Anne Klein, Calvin Klein, Oscar de la Renta, Halston, and the only black designer, Stephen Burrows. Out of the thirty-six models that attended, ten of them were black, making this one of the first noted moments of racial diversity on the runway. Although the show was a spectacle within itself, housing countless socialites clad in tiaras, jewels and haute couture clothing into the Palace for the evening, what has been most noted is the spectacle of black models that wore the garments of American designers that night–Jennifer Brice, Ramona Saunders, Pat Cleveland, Alva Chinn, Bethann Hardison, Charlene Dash, Billie Blair, Barbara Jackson, Norma Jean Darden and Amina Warsuma. In the documentary about the runway show, Versailles ’73: American Runway Revolution (Draper 2012), curator-in-charge at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Harold Koda notes that these “African American models animated the stage,” and notes that prior to this time, black models were not present in couture shows. One of the most esteemed models selected to walk for each of the five American designers, Pat Cleveland, notes that although the black models were considered a spectacle and revolution to others, it was “the core of who we were.” She notes that the black models were the American designers’ arsenal; “what no one else had…so the thing that may have been thought a flaw became the pearl (Draper, Ibid).” That very flaw that Cleveland discussed in Versailles ’73 was her blackness. It was a flaw that persistently permeates in and out of style in the fashion industry. A flaw that Barbara Summers elucidates in the documentary, when she states that these black models “who were possibly descendants of slaves to be the stars in this magnificent, shielded chateau” was indeed a major impact and revolution for the fashion industry (Draper, Ibid). Summers’ discussion of slavery is the very place we must start to understand, first, how blackness came to be used as a means of fashionable style, and, second, how temporality, this concept of blackness as a trend, came to be recycled over time.

In her analysis of black dandyism, Monica Miller (Miller 2009, 10) links the construction of black identity to dress. During the Transatlantic Slave Trade, African captives were brought to the colonies unclothed; “their new lives (as slaves) nearly always began with the issuance of new clothes.” Likewise, Noliwe Rooks (Rooks 2004, 11) in her discussion of the way in which black women (as slaves) bodies came to be written about by white male journalists, writes how their dress came to be denoted to their servitude; “enslaved women working in the fields often were given little more than rags with which to cover themselves.” The linkage between slavery and clothing, perhaps lends itself to a wider construction of Stuart Hall’s (Hall 1997) “Other,” in which the black body, and its blackness, is marked as inferior and different to validate the Eurocentric norms of what beauty should and should not look like.

Sara Baartman set the tone for the representation of the black woman. During the 1800s, Baartman was brought to Europe from South Africa and was put on display for more than five years. Her body, rendered a “spectacle (Hall 1997, 264),” was ogled over by watchers, as they came to fetishize her large posterior and breasts. Under the Eurocentric, idealistic, white male gaze, she was summarized into nothing more than a beast, being caged and brought out on a chain, when it was time for her to be shown off to the public. As Hall writes, there was an “obsession” by the public to mark Baartman’s body and blackness as different.

In a more contemporary fashioning of the black body, Patricia Hill Collins (Collins 2000, 69) placed the stereotyping and marking of difference into four oppressive categories–the mammy, the black matriarch, the welfare mother and the Jezebel. In short, the mammy represented the servitude denoted to slavery (black women in head rags or wraps and aprons); the black matriarch represented the overbearing, angry black woman; the welfare mother represented the black woman’s dependence on government assistance, her laziness and lack to pursue a job; the Jezebel represented, perhaps the most proscribed stereotype to black women, as hypersexual and using her feminine ways to woo not just men, but white men. These oppressive images worked to fashion the black body into modes of inferiority and mark them as different in order to stabilize the Eurocentric ideals of beauty into societal acceptance.

However, pivotal movements began to shift the experiences and representations of black American’s lives, such as the abolition of slavery; the Mecca of the New Negro in the 1920s; the push for integration; voting rights; and movements for Civil Rights and Black Power. All of these historical moments allowed for a rewriting of blackness on black people’s terms. By the twentieth century, there was a redefinition of blackness and the fashioning of the black body, as members of black society came to fashion themselves, and white mainstream culture took notice.

Something to Call Our Own

“Black Americans began to define themselves, subversively, by fashioning themselves through both style and thinking, combining their acculturation of Eurocentric oppression and sustaining their stable forms of style and fashion.”

In theorizing why we come to wear clothes, Entwistle (Entwistle 2000, 57) answers the question within the realms of anthropologists. She summarizes four explanations of adornment: protection, modesty, display and communication, which all come with varying contradictions. However, when attempting to answer the questions of why black Americans wear clothes and how that relates to their blackness, anthropological explanations don’t suffice. This is because, historically, their experiences with American adornment depended greatly on their captivity and servitude.

African captives were brought to the colonies unclothed (Miller 2009, 10); “their new lives (as slaves) nearly always began with the issuance of new clothes.” Thus, their identities came to be defined through oppressive dress that marked them as servants and even cattle (i.e. shackles). Furthermore, the first representations of wearing blackness came to be represented in the trading of black bodies. Slaves “were often used and regarded as luxury items and ornaments rather than laborers (Miller 2009, 39)” by their slave masters. Upon manumission, however, black Americans came to mix their oppressive, proscribed identity with the memory of their “Africanisms (Griebel 1995, 210)”— a preserved African identity that resonated among black Americans from slavery until present day.

Black Americans began to define themselves, subversively, by fashioning themselves through both style and thinking, combining their acculturation of Eurocentric oppression and sustaining their stable forms of style and fashion. Helen Bradley Griebel (Griebel 1995) writes extensively about the survival of the West African headwrap through the Middle Passage to the contemporary wearing of the headwrap by African Americans in the United States. During the twentieth century, working-class and middle-class blacks were beginning to pay homage to their African diasporic identity through dress. Griebel’s study of the headwrap works alongside Miller’s (Miller 2009, 4) “gestures of memory, individuality, and subversion” held on to by African slaves: “The accumulation of objects of personal adornment and the nature of their display mattered to materially deprived African captives. This is as true for those who never deliberately dressed in silks and turbans, whose challenge was to inhabit the clothing in their own way, as for those who were more humbly attired, who used clothing as a process of remembrance and mode of distinction (and symbolic and sometimes actual escape from bondage) in their own environment.”

Situating Griebel’s analysis of the preservation of the headwrap in the twentieth century leads to further unpacking of the TIME’s statement concerning the “temper of the times.” The publication is specifically alluding to the 1960s, carried well into the mid-1970s, in which black women transgressed from Patricia Hill Collins’ oppressive categories to beautiful during a reclaiming of black identity in the black community, and an acknowledgment of that reclamation, by the white mainstream media.

In 1965 Donyale Luna became the first black woman to appear on the cover of a major women’s magazine when a sketch of her appeared on the cover of Harper’s Bazaar (Harper’s Bazaar 1965); the following year she would become the first black model to appear on the cover of British VOGUE (British Vogue 1966). In 1968 Naomi Sims became the first black model to appear on the cover of Ladies’ Home Journal (Ladies’ Home Journal 1968); the following year she became the first black model to be featured on the cover of LIFE (Life Magazine 1969). And, Katiti Kironde became the first black model to appear on the cover of Glamour (Glamour Magazine 1968) in the same year. In 1973 ten black models from the Versailles show in France revolutionized the way black women were seen on the runway. In 1974, Beverly Johnson became the first black woman to appear on the cover of VOGUE (Vogue Magazine 1974). The arrival of black models on the covers and inside the pages of mainstream fashion publications was not by chance, but rather due to a cultural shift in the twentieth century (Johnson and Prijatel 2007, 117), which transformed the world of publishing, redefining both womanhood and black beauty as a mode of consumption.

Prior to Luna, Sims, Johnson and additional black models whom started to become firsts in fashion, “mainstream magazines did not speak to African American women at all (Rooks 2004, 21).” The cultural changes in the twentieth century referenced gender and class dynamics for both white and black women, as they were beginning to be considered active consumers. However, mainstream fashion publications were still negligent in covering concerns of African American women, such as societal issues on race and injustice, as well as black beauty concerning hair and cosmetics; thus causing many black women to turn to publications written and owned by the black community (M. L. Craig, Ibid).

Unlike a subculture, in which members of the group fluidly deviate from dominant culture (Hebdige 2007, 257), black people, both the middle and working class, were subverting inward, returning to their roots in order to define themselves against the racial group that they had been constructed to be. This redefinition was realized specifically in the late 1960s, in which black women began to wear their hair in its “natural”state, mostly styled into an Afro. Although met with contempt among predecessors within the black community, young black women, many of them participants in the Civil Rights and Black Power movement, experienced a sense of transgression, in which their identity was finally being defined on their terms: “It [the Afro] was proof that the Eurocentric beauty standard had been overturned, and as a result, the brown skin and tightly curled hair that had been black women’s ‘problems’ were suddenly their joys (M. L. Craig 2002).”

That black women’s natural hair was once their “problem” gives way to a wider context of embodied oppression. Before being considered beautiful, the black woman and her blackness was ugly, defined by both white superiority and internalized self-hatred within the black community. Moreover, this idea of blackness as a “problem” aligns with Pat Cleveland’s statement on the 1973 Versailles show, in which she would have normally been considered a “flaw;” however, due to twentieth century societal shifts, she had indeed become a pearl.

The Civil Rights and Black Power movements set the tone for racial pride and the reclaiming of black identity. The Civil Rights Act passed in 1964, followed by the Voting Rights Act in 1965. Pivotal Civil Rights leader Malcolm X was assassinated the same year; and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination followed in 1968. In the same year, singer James Brown released his single Soul Brother No. 1, which stamped the mantra “Say it loud / I’m black and I’m proud” into the minds of black people worldwide, as the “temper of the times” became a mode of resistance against oppression, while also working itself into the images of white mainstream consumption.

Despite the mainstream fashion industry’s acknowledgement of the “black is beautiful” movement, their use of the model’s blackness came to be reified and codified. While the black community came to redefine their identity, mainstream white publications toned down their racial pride and instead began to reify black models alongside Eurocentric ideals. Although Donyale Luna was of a lighter complexion, the sketch of her on the cover of Harper’s Bazaar could have easily lent itself to the assumption that she was a white woman; neither Naomi Sims, Katiti Karonde nor Beverly Johnson donned Afros; and it appeared that publications were primarily focusing on “large-boned, dark-skinned women,” which “would be represented as the primary purveyors of fashion’s message (Rooks 2004).” Their beauty, although reclaimed and redefined, was represented in dominant cultures within the realms and negotiations of white, patriarchal standards (Hall 1997, 253). Albeit the fashion industry was finally inclusive of black models in fashion, their blackness was still constructed into merely a moment; their identity as marketable would soon become packaged into trends that lent themselves to appropriation and lack of representation.

Now You See Me, Now You Don’t

“The fashion industry seems to have returned to marking the difference of blackness and codifying its representation.”

Despite the arrival of black models in the mainstream fashion industry in the late 60s and early 70s, there has been an evident lack in progress concerning a balance of diversity, which calls for equal representation based on women of color. In 2013, retired supermodel Bethann Hardison (The Diversity Coalition 2013) —a black model from the 1973 Versailles fashion show—sent letters to the Council of Fashion Designers of America, The British Fashion Council, Camera Nazionale della Moda Italiana and Fédération francaise de la Couture, writing that fashion design houses fall short in its use of models of color in their Fashion Week lineups. She and her organization, The Diversity Coalition, wrote, “no matter the intention, the result is racism.” They state that the designers’ actions, “reveals a trait that is unbecoming to modern society.” The letter concluded with 25 design houses that had performed “this racist act.” In 2014, she and the Coalition sent follow-up letters listing the designers that had improved from the season before, but writing that there are “still design houses serviced by casting directors and stylists who are latent, as they seem comfortable with stereotypical images (The Diversity Coalition 2014).”

If the Versailles fashion show in 1973 was one of the most noted moments of diversity on fashion runways, then why in 2013 are designers being accused of the opposite? There must have been a time when blackness went out of style, according to the dominant culture, which is most representative of the mainstream fashion industry. Thus, my argument concerning the trending of blackness persists, due to present evidence that displays how the inclusion of blackness in fashion has certainly been modified but stereotyping is ever-present (Hall 1997, 250).

In his analysis of Robert Mapplethrope’s “Big Black Book,” Kobena Mercer writes (Mercer 1994, 194): “It is the problematic enunciation that circumscribes the marginalized positions of subjects historically misrepresented or underrepresented in the dominant culture, for to be marginalized is to have no place from which to speak.”

Bethann Hardison and the Diversity Coalition did not necessarily resurface the conversation of racial diversity in the fashion industry. Black designers, models, etc. have to navigate through their careers based on their race quite frequently. Even though Chanel Iman was the youngest Black model to appear on the cover of Vogue, designers have told her “they already have a black girl” (Wilson, Chanel Iman Talks Racism In The Fashion Industry: ‘We Already Found One Black Girl. We Don’t Need You’ 2013). Long-time editor at Vogue, André Leon Talley, waited until he left his post of managing editor at the highly esteemed publication to publicly voice his opinions on race in the fashion industry (Persad 2014). He lives “in a world of whiteness and success,” and notes that there are few or no black executives or designers who hold credibility or recognition within the realms of the mainstream fashion industry. Furthering his reflection, he considers racial tensions in not only the fashion industry, but also America, discussing how it greatly relates to the civil rights era and the discomfort the mainstream feels in discussing issues of race.

Numéro Magazine painted a white model in blackface for its 2013 “African Queen” editorial. Photo: Numéro

Racial progress seems to be a figment of imagination. The cyclical nature of racial oppression is more evident now than ever. Recent marches and protests in support of Ferguson and against police brutality greatly resemble marches from the Civil Rights and Black Power movement. Even the fashion industry seems to have returned to marking the difference of blackness and codifying its representation. Vogue’s (Garcia 2014) October 2014 online article on the big booty declares the way in which the mainstream has claimed the booty for themselves, deactivating the historical subordination that has allowed for oppressive, racial semiotics of the big booty, which has often been associated with the subordination of black women. Elle (Prescod 2014) published an article on Timberland boots, claiming the shoes’ acceptance by the dominant culture while greatly ignoring the association of the boot with black hip-hop culture. Fashion designers have perpetuated stereotypes on the runways, choosing to mostly use models of color when showing spring or summer collections, representing the exotic, tropical and mystic nature of blackness. Dolce & Gabbana (Phelps 2012) integrated caricatures reminiscent of Patricia Hill Collins’ aforementioned mammy into its spring 2013 collection. Numéro Magazine (Wilson 2013) painted a white model in blackface for its 2013 “African Queen” editorial. Interview (Refinery 29 2010) placed a white model amid a group of black men and women in its “Let’s Get Lost” editorial. Lebron James—the first black man to appear on the cover of Vogue—greatly resembled a poster that was used to promote the film King Kong (USA Today 2008). As the democratic atmosphere of the Internet permits, many continue to spread the word of the negligence in diversity and the misuse of blackness, which continues to situate the constructed race of being black into a position of silence and powerlessness.

In interviewing an emerging black fashion designer, Charles Harbison, who has presented at New York Fashion Week and has been featured in Vogue and InStyle, he remembers a specific anecdote about experiencing his blackness (Harbison 2014): “I was working at a particular house and we were doing castings and the creative director was putting this woman model–black model–into a bunch of different looks, and I thought she looked amazing in everything. And he didn’t know what to do with her and the look. And I had another designer look at me and say, ‘You know, Charles, it’s just so hard to make the black girls look expensive.’”

This is a huge shift from black bodies being worn as luxury items during the Transatlantic Slave Trade to now their bodies being considered inexpensive. The temporality of their blackness concerning fashion has shifted from luxury item to celebrated beauty, the codification of that beauty and the selling of that beauty. So often, blackness—and its gruesome history—can be rendered a garment that can easily be shed when a season no longer begs for its use. Regardless of its trendiness, its historical oppression and misrepresentation continues to be worn and experienced by those that it most truly represents–black Americans.

Bibliography

British Vogue. March 1966.

Collins, Patricia Hill. Black Feminist Thought. Psychology Press, 2000.

Craig, Maxine Leed. Ain’t I A Beauty Queen. Oxford University Press, 2002.

Versailles ’73: American Runway Revolution. DVD. Directed by Deborah Riley Draper. 2012.

Entwistle, Joanne. “Theorizing Fashion and Dress.” In The Fashioned Body: Fashion, Dress and Modern Social Theory, by Joanne Entwistle, 57. Polity Press, 2000.

Garcia, Patricia. “We’re Officially in the Era of the Big Booty”. September 9, 2014. http://www.vogue.com/1342927/booty-in-pop-culture-jennifer-lopez-iggy-azalea/ (accessed September 28, 2014).

Glamour Magazine. August 1968.

Griebel, Helen Bradley. “The West African Origin of the African American Headwrap.” In Dress and Ethnicity: Change Across Space and Time, by Joanne B. Eicher, 207-226. Herndon, Virginia: Berg Publishers Limited, 1995.

Hall, Stuart. “The Spectacle of the Other.” In Representation: Cultural Representation and Signifying Practices, by Stuart Hall, 225-285. Sage Publications and Open University, 1997.

Harbison, Charles, interview by Rikki Byrd. N/A (October 10, 2014).

Harper’s Bazaar. November 1965.

Hebdige, Dick. “Style.” In Fashion Theory, by Malcolm Barnard, 257. New York City, New York: Routledge, 2007.

Johnson, Sammye, and Patricia Prijatel. The Magazine from Cover to Cover. 2nd. New York, New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Kawamura, Yuniya. “Fashion-ology.” In Dress, Body, Culture. New York: Oxford, 2005.

Ladies’ Home Journal. November 1968.

Life Magazine. October 17, 1969.

Mercer, Kobena. “Reading Racial Fetishism: The Photographs of Robert Mapplethrope.” In Welcome to the Jungle, by Kobena Mercer, 171-218. New York: Routledge, 1994.

Miller, Monica L. Slaves to Fashion: Black Dandyism and the Styling of Black Diasporic Identity. Duke University Press, 2009.

Persad, Michelle. Andre Leon Talley: ‘There Are Ceilings That I Have Not Broken That I Should Have Broken’. September 18, 2014. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/09/18/andre-leon-talley-ceilings-broken_n_5836866.html (accessed December 5, 2014).

Phelps, Nicole. Dolce & Gabbana Spring 2013 Ready-to-Wear. September 23, 2012. http://www.style.com/fashion-shows/spring-2013-ready-to-wear/dolce-gabbana (accessed December 5, 2014).

Prescod, Danielle. Timberland Boots Are the New Birkenstocks. October 7, 2014. http://www.elle.com/fashion/trend-reports/timberlands-fashion-birkenstock#slide-1 (accessed December 5, 2014).

Refinery 29. This Daria Werbowy Editorial For Interview Feels Rather Racist. May 12, 2010. http://www.refinery29.com/this-daria-werbowy-editorial-for-interview-feels-rather-racist (accessed December 5, 2014).

Rooks, Noliwe. Ladies’ Pages. New Jersey: Rutgers University Center, 2004.

Simmel, Georg. “Fashion.” Edited by Daniel Leonhard Purdy. The Rise of Fashion (University of Minnesota Press), 2004: 289-309.

Sombart, Werner. “Economy and Fashion: A Theoretical Contribution on the Formation of Modern Consumer Demand.” Edited by Daniel Leonhard Purdy. The Rise of Fashion (University of Minnesota), 2004: 310-316.

Summers, Barbara. Skin Deep: Inside the World of Black Fashion Models. Amistad Press, 1998.

The Diversity Coalition. “http://balancediversity.files.wordpress.com/2013/09/balance-diversity-new-york.jpeg.” Balance Diversity. September 5, 2013. www.balancediversity.com (accessed September 10, 2014).

TIME Magazine. “Black Look in Beauty.” TIME, April 11, 1969: 90.

USA Today. LeBron James’ ‘Vogue’ cover called racially insensitive. March 28, 2008. http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/life/people/2008-03-24-vogue-controversy_N.htm (accessed December 5, 2014).

Vogue Magazine. August 1974.

Wilson, Julee. Chanel Iman Talks Racism In The Fashion Industry: ‘We Already Found One Black Girl. We Don’t Need You’. March 18, 2013. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/03/18/chanel-iman-talks-racism-in-fashion-indsutry-_n_2900038.html (accessed December 5, 2014).

—. Numéro Magazine ‘African Queen’ Editorial Uses White Model Ondria Hardin [UPDATE]. February 25, 2013. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/02/25/numero-magazine-african-queen_n_2761374.html (accessed December 5, 2014