It’s not everyday that a Parsons Senior Seminar prompts a television producer to pick up the phone. But that’s just what happened last November, when ADHT’s Assistant Professor Susan Yelavich got a call asking her to talk about how she interprets Orhan Pamuk’s novel My Name is Red (1998) in her Design Fictions class. Producer Ross Tuttle—a New York-based journalist and documentary filmmaker—explained that he was working on a series for WGBH called Invitation to World Literature that would feature Pamuk’s Nobel Prize winning novel, along with classics ranging from Homer’s The Odyssey to Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things. In the process of looking for new perspectives on Pamuk’s tale of 16th-century Istanbul, Tuttle’s assistant Maggie Anderson had come across Yelavich’s syllabus online and noted that the chapter “I am a Tree” was among her readings.

It’s not everyday that a Parsons Senior Seminar prompts a television producer to pick up the phone. But that’s just what happened last November, when ADHT’s Assistant Professor Susan Yelavich got a call asking her to talk about how she interprets Orhan Pamuk’s novel My Name is Red (1998) in her Design Fictions class. Producer Ross Tuttle—a New York-based journalist and documentary filmmaker—explained that he was working on a series for WGBH called Invitation to World Literature that would feature Pamuk’s Nobel Prize winning novel, along with classics ranging from Homer’s The Odyssey to Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things. In the process of looking for new perspectives on Pamuk’s tale of 16th-century Istanbul, Tuttle’s assistant Maggie Anderson had come across Yelavich’s syllabus online and noted that the chapter “I am a Tree” was among her readings.

What’s the relevance of My Name is Red for designers? And why are they reading fiction in the first place? Yelavich responds that designers need to think about how their work lives in the world, and how it changes the world outside the studio. She says Pamuk’s fable is ideal for that purpose because, first and foremost, My Name is Red makes a compelling case for ‘style’ as a vehicle for cultural values.

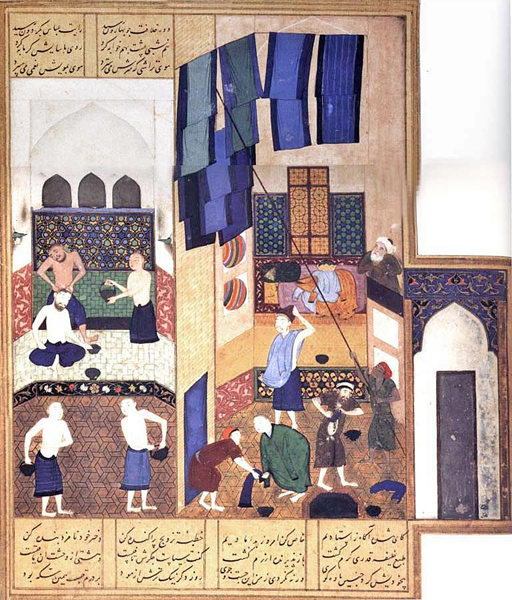

On the surface, My Name is Red is a mystery that centers on a miniaturist who’s been murdered by a fellow painter, upset by the Sultan’s secret commission of a book illustrated in the Venetian mode, with blasphemously realistic portraits. The Ottoman Empire is at its peak; yet, in this particular moment of globalization, Western influence is beginning to stir up tensions. Turkish miniaturists value the copy; Frankish painters, the original. In the Islamic tradition, realistic portrayals of the world are viewed as competing with Allah, the ultimate creator. In Renaissance Europe, the artist is taking center stage and signature styles are celebrated. A debate disguised as a novel, My Name is Red is really a portrait of values: Eastern communality and Western individualism.

Yelavich especially likes teaching the chapter that is narrated by a tree. In fact, the ‘tree’ is an unfinished drawing of a tree, alone on the page. He’s ambivalent about his state and confesses to enjoying being the sole object of attention. It appeals to his vanity, however sinful that may be. But by the conclusion of the chapter, the reader finds the tree thanking Allah that he’s not been drawn in the Western fashion. He says, “And not because I fear that if I’d been thus depicted all dogs in Istanbul would assume I was a real tree and piss on me: I don’t want to be a tree, I want to be its meaning.”

Despite the tree’s declaration fealty to aesthetics and ethics of Islam, the novel doesn’t campaign for (or necessarily against) the righteousness of a singular world view. Instead, Pamuk is more interested in the possibility of choice, especially the difficult kinds of choices that arise when we meet strangers, who have other ways of doing things. Yelavich wants students to be similarly sensitive to the cultural implications of their choices, particularly in view of current political debates about Islamic values and customs, both in Turkey and the world at large. And as an aside, she recommends Pamuk’s novel Snow (2004), which carries those debates in into the present, with equal measures of comedy and tragedy.

The segment of Invitation to World Literature devoted to My Name is Red can be viewed online at http://learner.org/vod/vod_window.html?pid=2332. Cast members include the book’s Nobel-prize winning author, Orhan Pamuk, and its English translator, Erdağ Göknar. The entire series (with teaching resources) can be accessed at http://www.learner.org/courses/worldlit, funded and distributed by Annenberg Media. Television broadcasts times will be announced at a future date.