As the title indicates, the exhibition at Rooster Gallery exonerates the artistic process from its confines of being a precursor to, but not a necessary part of, finished create works. The carefully curated show is more about the prolific artist’s process than it is about a glamorous display of an overarching oeuvre. As curator Kara Rooney notes in her catalogue essay, what makes this fourteen year span preceding Beuys’ death so significant is that his thoughts became his works. The time period marked a turn toward social sculpture theory and a simultaneous turning away from a theory of art as the output of standalone aesthetic products. Beuys says that “how we mold and shape the world in which we live results in the idea of sculpture as an evolutionary process.”[1] In other words, Beuys saw his work not as an afterthought or as the material conclusion of his thoughts, but inextricably bound up in the process and flux of life and social structures themselves.

Our worlds are molded and shaped not unlike the ways our lives, the decisions we make, the people we surround ourselves with, are molded and shaped to create a system, however harmonious or inharmonious our systems end up being. It’s in this literal shaping of life that Beuys saw the ramifications of this new sculpture theory on political and social ideology. Heavily influenced by Rudolf Steiner’s idea of the Threefold Commonwealth, Beuys too saw artistic action as inextricably linked to the political. The Threefold Commonwealth was Steiner’s solution to Germany’s flimsy political structure of the post-war mid-20th century, postulating a stark separation between the cultural, the political, and the economic.[2] As far as Beuys is concerned, his artwork from this moment on was developed from the ideologies of both Steiner and Marx. He sought to supersede or overcome aesthetic structure in the same way Marxism calls for an overthrow in the social-political.

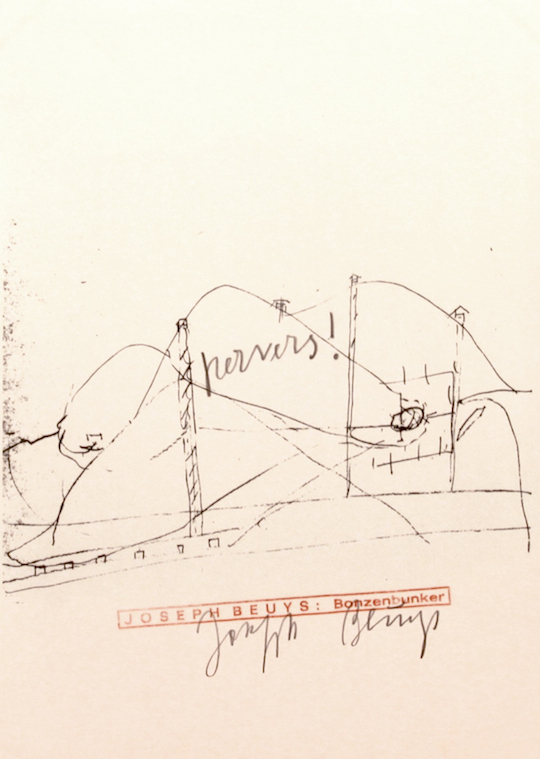

If we take Beuys’ theory seriously and believe that life and artistic processes alike function on a homogeneous plane, then (as Beuys both recognizes and encourages) everyone is an artist. But if everyone is an artist, is anyone an artist? If the whole world is blue, do we lose our ability to understand what it means for there to exist other colors? In other words, an entire world composed of artists renders the term ‘artist’ obsolete, since in order to be recognized as an artist, one must be recognized as not being a number of other things, (a doctor, lawyer, teacher, etc). Beuys’ ideology is problematic when trying to assess his ‘art’ in contemporary terms. If we buy into his theory, then his work is art simply by virtue of its being material processes which were formed from chaotic substances, regardless of what we think about the finished products on an aesthetic level. The theory pushes for a destabilizing of the working definition of aesthetics by widening it to include the things that we wouldn’t normally consider to be art. Like Kara Rooney aptly says: “By the mid-1970’s, art, for Beuys, was no longer a matter of creating objects; rather, it was to act as the vehicle through which change might be facilitated.”[3] But what kind of change is Beuys calling for? Bonzenbunker is a series of drawings overlaid with text more vibrantly rich than the sketches they cover up. With inscriptions translating to “Enemy of the people,” “Disgusting!” etc., Beuys doesn’t try to hide his political outrage. The question still remains: what kind of change is Beuys calling for which would appease or improve the German state, and how does his theory of social sculpture catalyze positive movements? The viewer is left wondering whether it’s politics that should be aestheticized, or aesthetics that should be politicized. “Consequently,” Beuys says, “everything that concerns creativity is invisible, is a purely spiritual substance. And this work, with this invisible substance, is what I call ‘social sculpture.’”[4]

What Beuys is advocating is a system in which each person recognizes their creative potential and acts upon on it in some way. This is really what he means when he claims that everyone is an artist, not necessarily that everyone is Picasso. What his ‘art’ pushes us to do is to stop seeing art as something separate, but as that which is indistinguishable from life processes and forces. When the two become one, Beuys’ theory of ‘social sculpture’ emerges, not as a theory of art but as a call for art to move beyond itself. Beuys recognized certain forces at play which propelled his anti-capitalist intuitions until his manifested in physical objects. The show at Rooster Gallery is truly one for its audience: it’s up to the viewer to decide whether they buy into the show as a show of art.

Joseph Beuys: Process 1971-1985 is on view at Rooster Gallery at 190 Orchard Street through February 9th.

[1] Kuoni, Carin, ed., Energy Plan for the Western Man: Joseph Beuys in America, New York: Four Walls Eight Windows, 1990 p. 19 in catalogue essay “Joseph Beuys: Process 1971-1985,” by Kara Rooney. http://roostergallery.com/JBeuys_Essay.pdf

[2] Stachelhaus, Heiner. ed., Joseph Beuys, New York: Abbeville Press, 1991. p. 37.

[3] Catalogue essay, Kara Rooney

[4] Catalogue essay