Home to a wealth of records that help to document the history of design, The Anna-Maria and Stephen Kellen Design Archives offer great insight into the lives and works of the famous and the unsung. Insights will regularly cover collections or items from the Archives that relate to research areas, events, or exhibits taking place throughout ADHT.

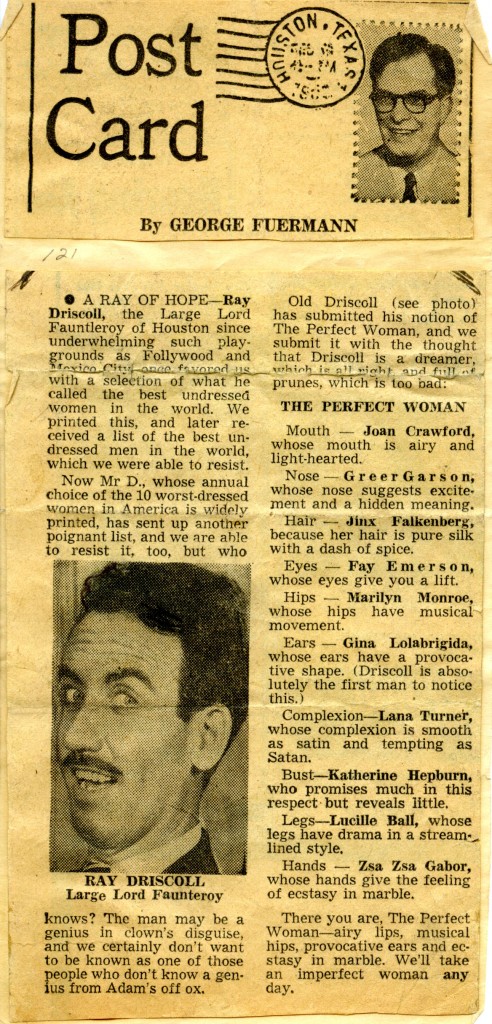

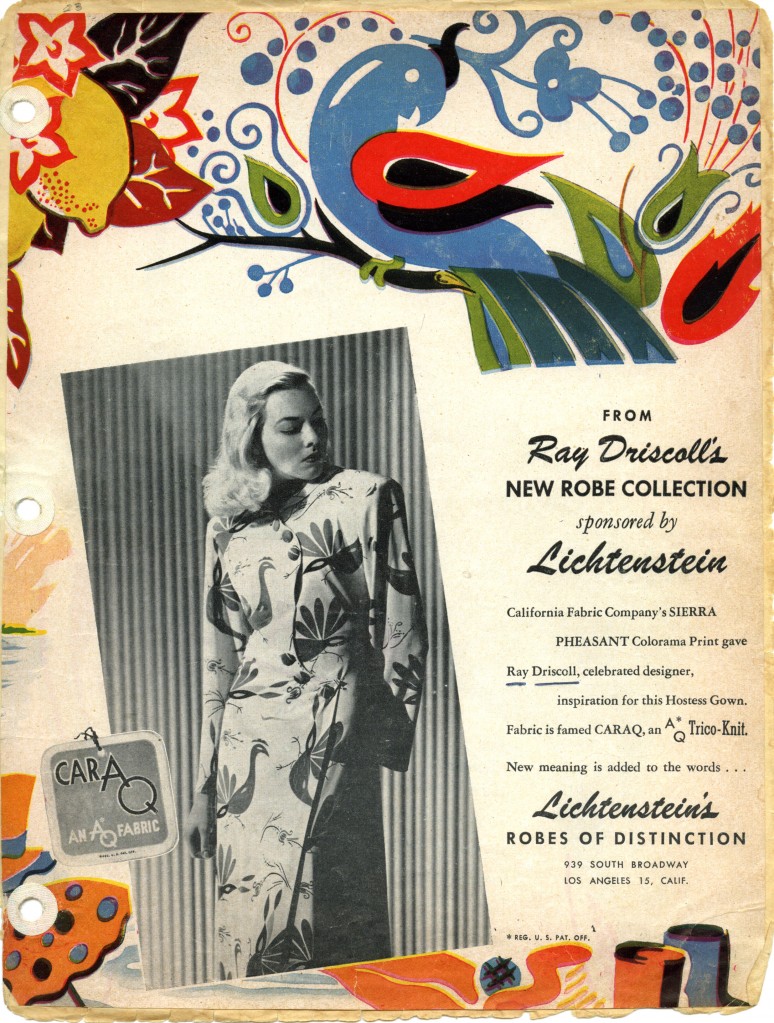

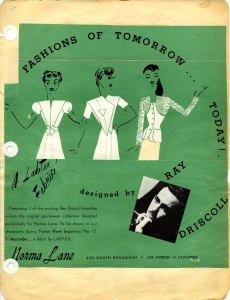

In celebration of this year’s Fashion in Film Series, we will explore the scrapbooks and fashion sketches of Raymond Driscoll. Once known as “Hollywood’s Bad Boy Fashion Designer,” Driscoll worked in the film worlds of Hollywood and Mexico City from the 1930s through the 1960s. He believed that “a gown must be emotionally disturbing to the onlooker,” and claimed to “have dressed and undressed more beautiful women than any other man in the world.”

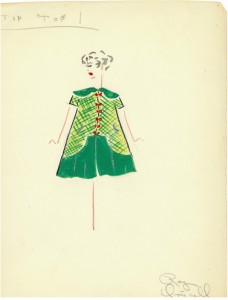

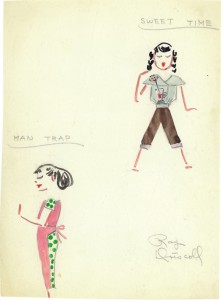

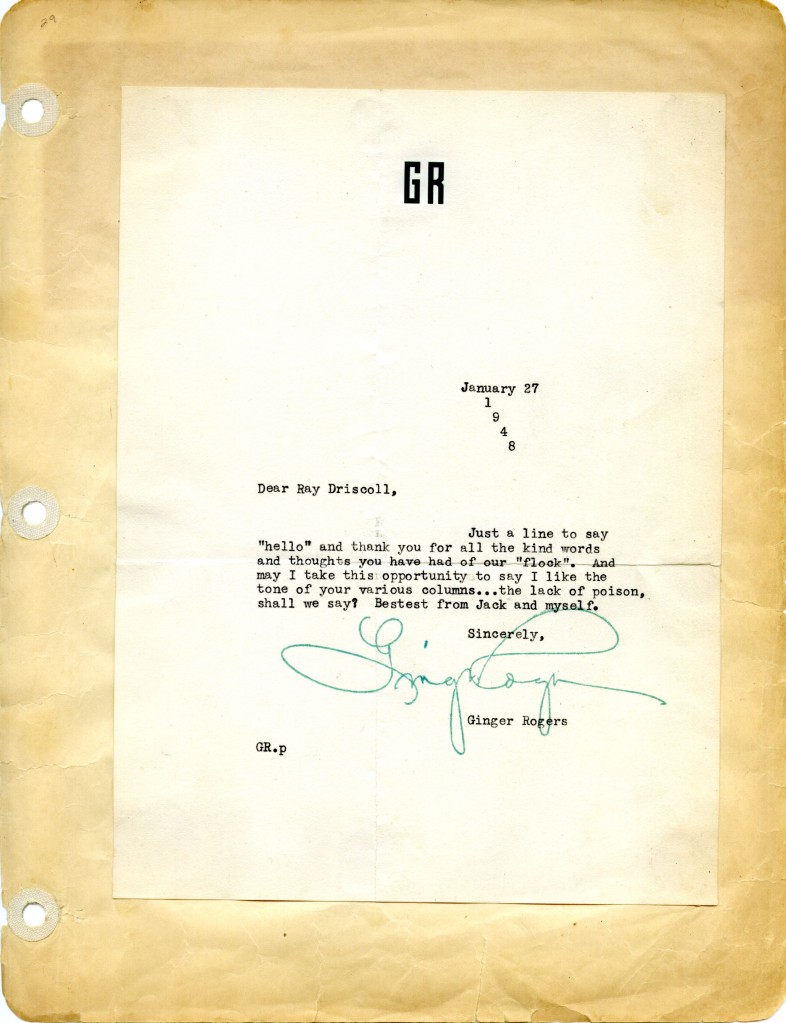

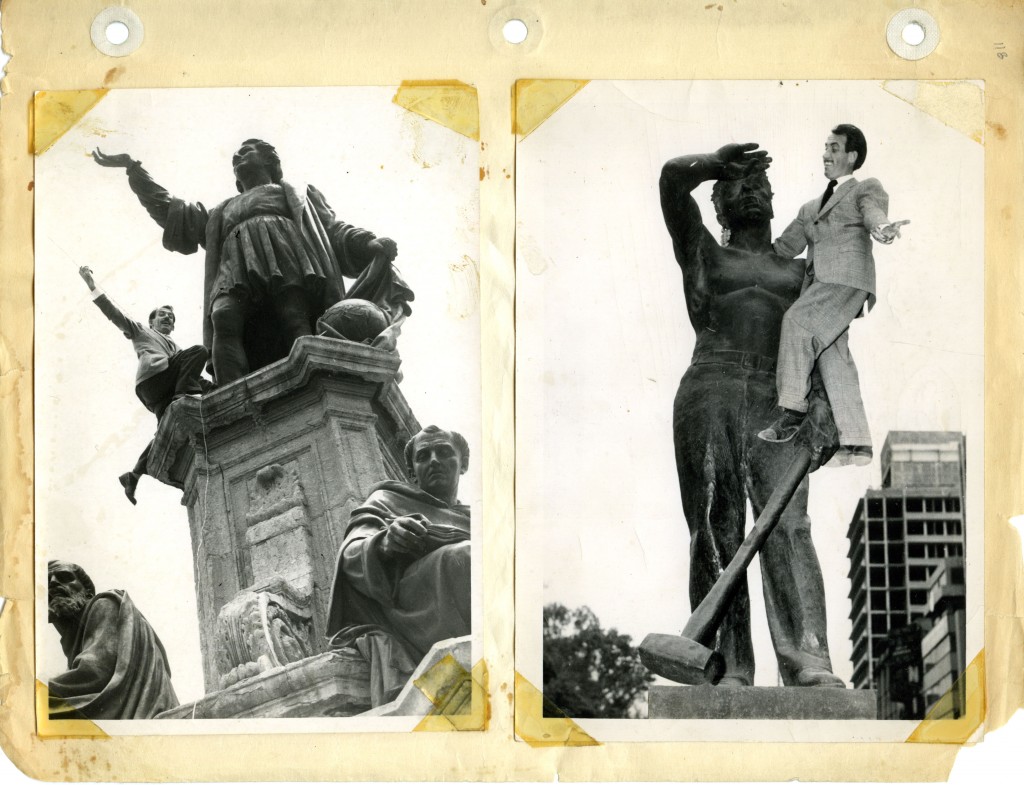

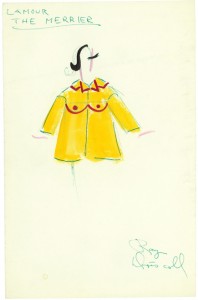

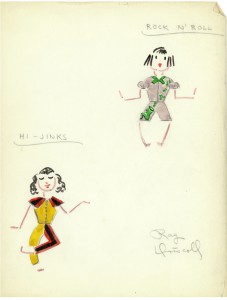

Driscoll reveals through these scrapbooks and sketches a lively, if at times eccentric, character. The scrapbooks contain correspondence with film icons and political figures, autographs from American and Mexican film stars, news and magazine clippings that depict his writings and designs, and endearingly playful photographs of the man himself. His watercolor and ink fashion designs for girls and women claim such whimsical titles as, “Male Bait,” “Frisky Foxy,” and “Tip Top!”

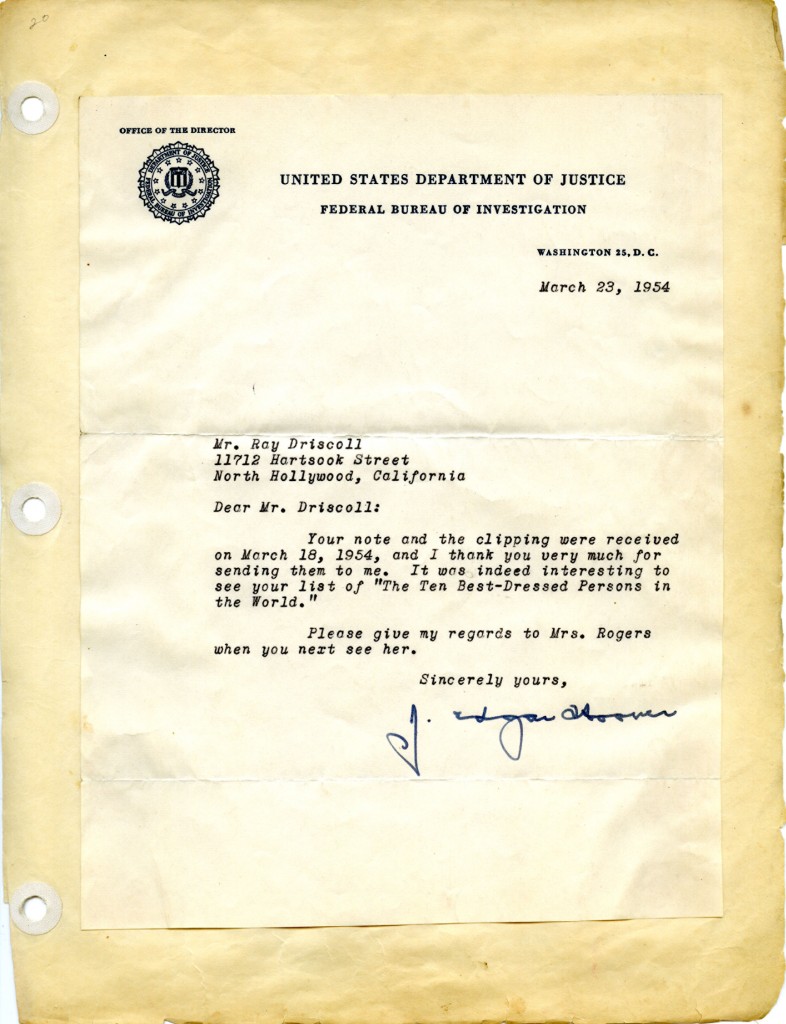

Famous in his day for penning biting celebrity “best-dressed” and “worst-dressed” lists, he was sued by Judy Garland for defamation of character when he marked her among the “worst-dressed” for “[dressing] like a tired clubwoman.” On the other hand, his scrapbooks are well populated with letters of thanks from those he praised in his “best-dressed” lists – the Duchess of Kent, J. Edgar Hoover, and Ginger Rogers, among others.

Wendy Scheir, Director of the Kellen Design Archives, and Jenny Swadosh, Associate Archivist, discussed how they acquired the Driscoll collection, what we know about him as a designer, and some of the challenges involved in conserving this type of material while providing access to it for researchers. Jenny Swadosh provides detailed responses to my questions below.

Q: How did the Kellen Design Archives acquire this collection?

A: Raymond Driscoll died in 2004 while residing at the Gershwin Hotel, where he had lived the last 40 years of his 90-year life. The hotel’s manager called the Kellen Design Archives, told the archivist about the presence of the scrapbook and sketches among Driscoll’s belongings, and asked if Parsons would like to have them. Driscoll’s estate was being handled by the Public Administrator’s office in the absence of any known family or heirs. There was no Parsons connection other than the fact that the manager associated Parsons with fashion design. We’re obviously very grateful she did because it has been a valuable collection for the Kellen Design Archives and we use it in archival instruction classes.

Q: What are some pieces you find especially striking or telling from the collection?

A: I continue to be awed by the thank you letter from J. Edgar Hoover. Of course, I am approaching it from the vantage point of someone living in the 21st century who knows about Hoover’s personal life and we now have access to records that Driscoll as Hoover’s contemporary would not have been aware of. However, the most telling part of the collection is the scrapbook in its entirety as a document of Driscoll’s activities across a twenty year span.

Q: Can you tell me a bit about who Raymond Driscoll designed for, who comprised his clientele, and which films he made costumes for?

A: What we know of Raymond Driscoll’s design career comes from the scrapbook he created, so we have to keep that subjectivity in mind. We only know what Driscoll wanted to remember. He has essentially edited his own history. I have not been able to confirm his association with the House of Worth, but the hang tags and the tear sheets in the scrapbook seems to indicate he was selling his designs to George Kateb, Norma Lane, and other sportswear and loungewear firms. The sketches in the collection are for women’s and girl’s apparel. He designed pantsuits, swimwear, and gowns. According to the clippings in the scrapbook, he also designed some fairly outlandish couture pieces for wealthy Hollywood clients, like apparel adorned with diet pills for a woman who owned a weight reduction spa. As far as film costumes, we haven’t been able to compose a list of his credits. He’s not in IMDB, but many costume designers are not. It would probably take some dedicated research in California and in Mexico City to establish a filmography for him. We invite intrepid scholars to take on this assignment.

Q: When I seek information about Raymond Driscoll online, little shows up. It seems, based on the collection’s pieces, that he was well-known in his time. Fashion advertisements noted his name. Stars and political figures thanked him personally for “best-dressed” reviews. Why do you think his name has evaporated — at least from the internet’s radar — with time?

A: For one thing, publicity is hard work. It’s an occupation in and of itself, and the labor involved is not always noticeable. Driscoll probably didn’t have a publicist aside from himself, although we don’t know that for certain. In the archival world, we talk about archival records being the by-product of an activity. The advertisements and the gossip column clippings and letters from celebrities are by-products of Driscoll’s seemingly relentless self-marketing activities. Names like Cardin and Dior live on long after the individual dies because various entities are engaged in activities to keep those names viable; the same cannot be said for Raymond Driscoll. There are many fashion designers who were household names not too long ago and nobody references them now, and this absence is not entirely dependent upon the actual enduring value of one’s work.

Also, most of the world’s collective information is not available online and, for a myriad of reasons, it never will be. This is the part of the interview where I plug archival research!

Q: There’s a great sense of whimsy and play here – in the zany photographs of Raymond Driscoll and in the spirited titles he gave his designs – Hoopla, Beau Catcher, Finders Keepers. Can you talk a bit about how important persona was for fashion designers at the time, and what role you think he filled?

A: I am not an expert on fashion history — that’s the job for ADHT students and faculty! — but I think there is a belief that our contemporary obsession with celebrity is somehow a new development. Clearly, it’s not, and other collections in the Kellen Design Archives corroborate this. In some ways, Driscoll reminds me of the character Paul Reubens created in Pee-Wee Herman, and it’s not just the physical resemblance. Driscoll acted as a court jester for Hollywood.

The other fascinating aspect of Driscoll’s career was his extolling of Mexican women as the 1950s feminine ideal. I highly recommend the book The Invention of Dolores Del Rio by film scholar Joanne Hershfield for insights into American culture of that era and what Driscoll may have had to gain from being associated in the press with Mexican and Mexican American actresses.

Q: If you’d like to talk about the process and adventures of archiving, particularly in relation to this collection, feel free to give me any information you’d like.

A: We gave the preservation and conservation of this collection a great deal of thought. The scrapbook was not in good condition when it arrived here. It has a lot of newspaper clippings in it, and, as anyone who has ever tried to keep a newspaper clipping knows, newsprint is highly acidic, which means it yellows and becomes brittle quite rapidly. The acid can also migrate, leaving discolorations on surrounding materials. Additionally, the adhesives from the Scotch tape Driscoll used had completely dried up, so items formerly taped to the pages were falling off every time the page was turned.

What we didn’t want to do was completely dismantle the scrapbook pages. Driscoll clearly put a lot of thought and labor into creating and composing them, and we wanted to keep it as close as possible to the form in which he made it. Archivists believe that the very order in which someone chooses to put things can offer valuable information about the person–in Driscoll’s case, the care he took with each page shows how much the scrapbook meant to him, and also tells us something about how he wanted to present himself.

So, we decided to use archival three-ring binders to house the scrapbook. Each page was inserted into a special, chemically stable plastic sleeve and snapped into the album in the same order in which Driscoll had originally arranged the pages. Now, researchers can handle the scrapbook without damaging it, we have slowed the deterioration of the clippings, and we do not have to worry about acid migration.

Eventually, when we have more time and money, we plan to digitize the collection and make it available to researchers online–creating a virtual version of the scrapbook. This will work as a preservation measure, as well, by reducing unnecessary handling of the original. And, importantly, it will provide an opportunity for a wider audience to discover Raymond Driscoll, and to deliver his unique world from undeserved obscurity.

For additional information on The Raymond Driscoll Collection housed in the Anna Maria and Stephen Kellen Design Archives, contact Wendy Scheir or Jenny Swadosh for an appointment by emailing kac@newschool.edu.

-Rebecca Nison