UPDATE: Click here to read The Atlantic’s piece on Professor Brody’s latest work, Housekeeping by Design.

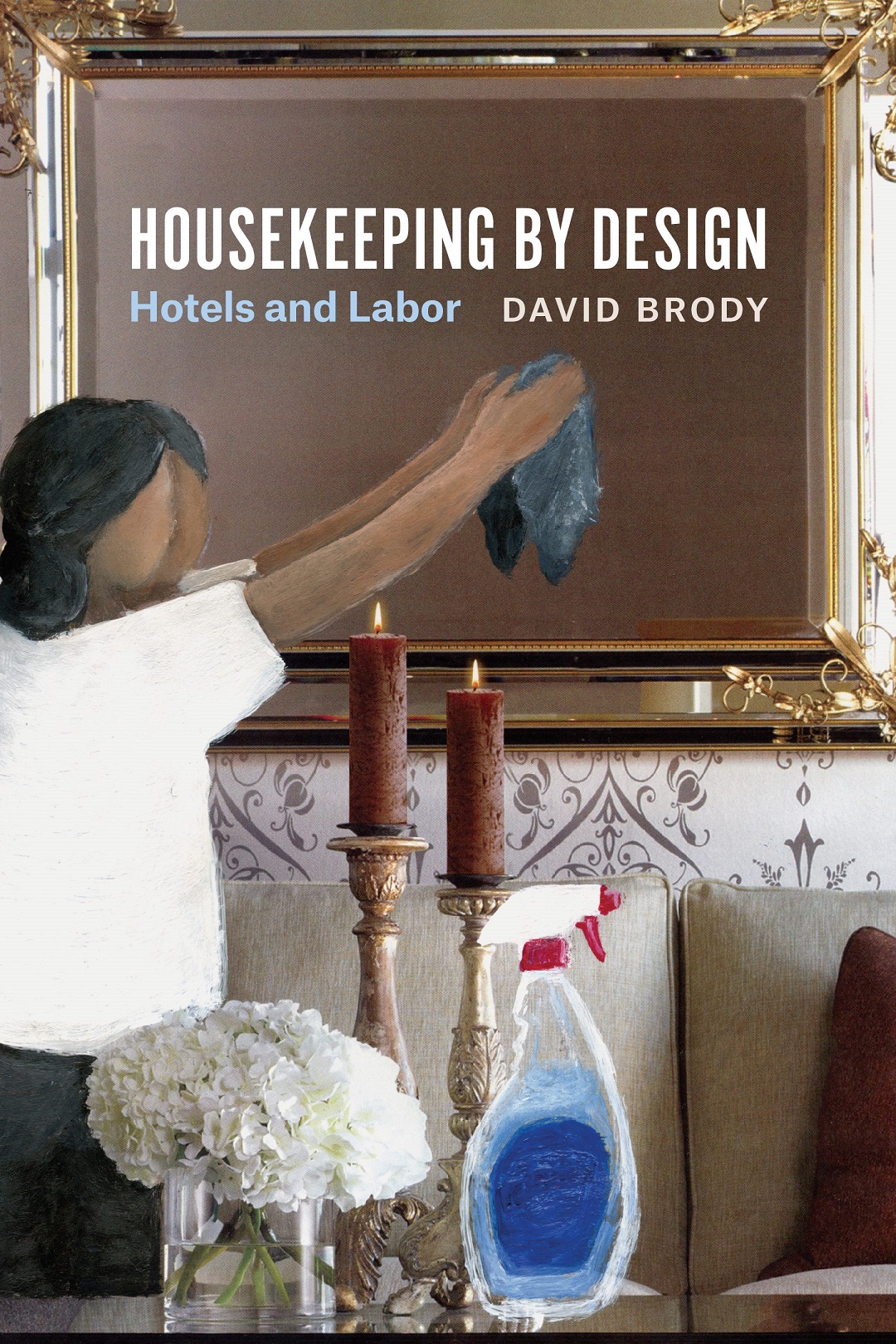

David Brody, ADHT Associate Professor of Design Studies, pulls readers into the unseen world of hospitality labor in his recently published book, Housekeeping by Design (University of Chicago Press, 2016).

A specialist in material culture, visual culture, and design studies, David teaches the undergraduate course ‘Topics in American Design,’ as well as the graduate level course ‘Theorizing Luxury’ at Parsons School of Design. His previous works include Visualizing American Empire: Orientalism and Imperialism in the Philippines (University of Chicago Press, 2010) and Design Studies: A Reader (Berg, 2009), which he co-edited with Hazel Clark. Other publications include articles and reviews in Prospects: An Annual of American Cultural Studies, Journal of Asian American Studies, American Quarterly, Journal of Design History, American Periodicals, and Design and Culture.

Through Housekeeping by Design, we witness the incredible amount of hard physical work that is involved in cleaning and preparing a room, how spaces, furniture, and other objects are designed to facilitate a smooth flow of hidden labor, and, crucially, how that design could be improved for workers and management alike if front-line staff were involved in the design process.

What drove you to study design and its implications in the hospitality industry?

I have been interested in the connections between design and culture for some time, but the relationship between design and labor is one area that has not been studied enough. The hotel industry is the perfect example that encapsulates so many of the complicated ways in which design can make our lives difficult or easier, especially if we can consider the difficult, physical labor that attends the work of housekeeping. I also have been more interested in questions about service design and hotels are venues where interior design and service design function in tandem in complicated ways that were fascinating to explore.

What surprised you in your research on this topic?

My biggest surprise was the research I did in Hawaii on Starwood Hotels and Resorts’ Make a Green Choice program. The program allows guests to opt out of housekeeping for up to 3 days in exchange for either rewards points or vouchers that can be used for food. Starwood, like other hotel management companies, celebrates the program as a progressive model of sustainable thinking that saves on chemicals, water, and electricity. What shocked me was the ways in which the program negatively affected housekeepers. It made their work more difficult, since they now had to clean rooms that had not been maintained for up to 3 days. It also created service design challenges, as the scheduling of work became more complicated in these hotels where so many guests were making a green choice. And finally, I was very surprised that housekeepers were losing money, since there were fewer rooms to clean. What on the surface appeared to be a progressive choice was actually very bad for these workers’ lives.

What was the scope of the research that is covered in Housekeeping? Do you have any particular stories or experiences from the research phase worth sharing?

I like working with unorthodox archives. While interviewing housekeepers changed the nature of this project in all kinds of important ways, I also investigated examples from popular culture, like the television show Hotel Impossible and the film Maid in Manhattan, which helped me explore how we perceive and represent hotel work. The research projects I worked on earlier in my career always involved historical figures, people who could not speak to me beyond the written word or object I was analyzing, so I loved getting insight from hotel workers who I could have actual conversations with.

A salient aspect of the information presented in your book seems to be the fact that the hard work that goes into hotel upkeep is deliberately kept hidden. What do you think this signifies?

The invisible nature of this work is what makes the guest experience at hotels, especially luxury hotels. It’s interesting, but guests do not mind watching a front desk clerk work to find them a better room. They don’t mind witnessing a concierge finding them the perfect dinner reservation. However, guests do not want to see housekeepers clean their rooms. The idea that this work has to get done, but is conducted in a way that hides labor, is one of the key issues that I focus on in my book. And, of course, design is what facilitates the concealment of this labor.

What are some problematic characteristics of design and its relation to hospitality, and can you share your thoughts on any alternatives? Are there any characteristics that find to be positive/valuable?

The biggest concern that I have is that hotels are designed without the insight of the hotel worker. If housekeepers had more of a say in the design process there would be less labor conflict and suffering, which is far too prevalent in the industry. I argue that a form of co-design, where workers could participate in design decisions, would change the industry for the better. For instance, far too many hotels now bring burdensome, heavy mattresses into their rooms. These mattresses lead to physical injuries, as housekeepers have difficulty working with this cumbersome bedding. If housekeepers could have conversations with management and designers about these heavy mattresses, my sense is that alternatives could be found that would drastically improve work conditions.

What do you hope readers will take away from Housekeeping?

I hope that readers start to think more about the relationship between design choices and workers. The way that spaces are constructed and the manner in which we design workflow systems and experiences have a tremendous impact on those who are tasked with maintaining our designed world. I want readers to come away from my book with more empathy towards the worker who must contend with a world of design that she may not have had any agency in creating.