by Jilly Traganou

Drone flying in “Research and Methods” class presentation by Mehdi Salehi. Photograph by Mathew Mathews.

“Of course, all the students want to see the big drone flying. A loud, unpleasant noise fills the room immediately. The black and white aircraft floats stably in the air and creates a strong draft in the room, which is apt to produce goosebumps. I am impressed by how insecure I felt. Of course, this drone was not equipped with weapons or other harmful objects. However, the propeller and its speed give me a queasy feeling. No one in the room wants to get too close to it or even feel the propeller near his or her skin. The drone moves around the room like a foreign body, almost like a dangerous animal whose intentions are uncertain and difficult to read, but always ready to attack.” (Lisa Merk, MA Design Studies student )

Reflecting on an experience shared by first-year MA Design Studies students in the “Research and Methods” class I taught this past semester, Lisa Merk notes that drones are “always ready to attack.” Is attack written in the DNA of drones, not unlike that of a gun, despite their disguise as cameras or dancers? Or can drones contribute to precisely the opposite—humanitarian goals—making aid more effective? These are merely different ways to ask the long-standing question: Do artifacts have politics?

Drone flying in “Research and Methods” class presentation by Mehdi Salehi. Photograph by Mathew Mathews.

I asked my students to consider these questions and others involving how we, as design thinkers and practitioners, feel about the prospect of a society living with drones during two months of research on the subject. As a class, it was not possible to arrive at a common conclusion, however, our multifarious engagements with drones derived various ways of thinking about the design, consumption, and afterlife of drones beyond their fad-like appearances.

Drones originally came into the public eye as combat equipment with high degrees of precision and access, “humanitarian weapons” that were meant to attack selective targets and avoid mass killings (Sandvik and Lohne 2014). Not a day passes without recognizing this fallacy, as combat drones mistakenly strike hospitals, civilians, and children. Both activists and scholars challenge the spread of drones as well as condemn their patriarchal militarism, their totalitarian disposition, and their method of “bureaucratized killing” (Asaro 2013). Following this mode of thought, if drones are born to kill, we are faced with a phenomenon analogous to that of the acceptance of nuclear energy in the 1970s and a “nascent drone feminism” is increasingly seen in contemporary activist practice (Feigenbaum 2015).

Not unlike other military technologies that were brought back home such as the Internet or GPS, the drone has also assumed unplanned functions much beyond its military upbringing. Drones are used today in aerial photography and there is serious investment in exploring their potential to act as couriers. And at the same time, designers are exploring the use of drones in a myriad of other directions, as art tools and humanitarian aid. Trying to avoid preconceived ideas of drones, we decided to look of the drone as socio-technical phenomenon that poses both a designerly and political challenge. The drone is an assemblage of thingy and humanly attributes: sensors, batteries, interface, will for control, curiosity, speculation, ingenuity. How are humans becoming different with drones under their control? What is in the mind of the designer who is grappling with them?

Group of students experimenting with drone photography in Medhi Salehi and Kristen Kersh’s class. Photograph by Leticia Cartier Oxley.

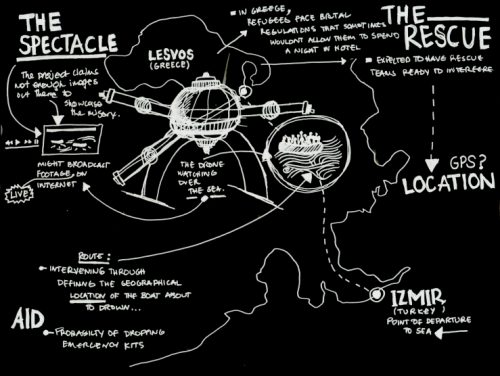

Our study began with ethnographic research of drones by looking at the design of drones at work and how their designers act with (or through) them. Studying drones in a setting like Parsons allowed us to dive directly into the work of the designer who is tinkering with them. Parsons labs never shy away from engaging directly with new technologies, taking a stance to devise ethical ways of engaging with the artificial, rather than opting for unengaged moralizing. Students became acquainted with the work of Parsons part-time faculty Mehdi Salehi and Kristen Kersh, early adopters of drones and founders of the startup Good Drones, whose studios explore possible drone applications. Mehdi and Kristen encouraged us to engage with their individual and pedagogical work by opening the doors to observation, feedback, and critique. One of their projects titled “Drones for Refugees” aims to help refugees who cross the Aegean Sea from Turkey to Greece. Students looked at the various technical problems that needed to be overcome for the project to take off, from limited battery life that allows for no more than 30 minutes of flying or dealing with the strong winds of the Aegean that threaten to detour the drone.

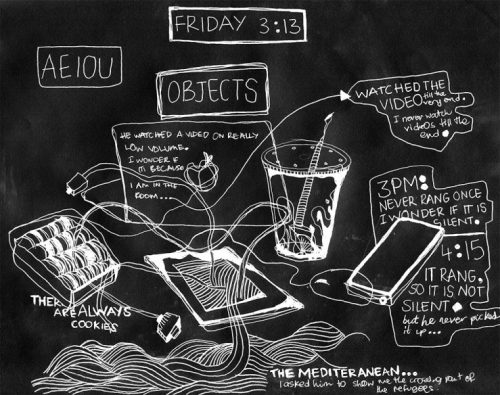

Participant observation of Mehdi Salehi’s work on the “Drones for Refugees” project and “Mapping the Humanitarian Drone Project” by MA Design Studies student Salma Shamel

“Mapping the Humanitarian Drone Project” by MA Design Studies student Salma Shamel

In Mehdi and Kristen’s drawing table, the drone is a combination of high technology equipment attached with super glue and duct tape—trial and error mixed with techno-determinism but also with skepticism. Besides observing, the students’ role became that of a skeptic that increased the designer’s self-doubt: Would the unmanned intervention in the sea allow for the saving of lives in a way that is not currently possible? Or would it be a dangerous tool if it finds its way in the hands of xenophobic individuals or law enforcement authorities?

MA Design Studies student Leticia Cartier Oxley learning to fly a drone. Photograph by drone.

Some Design Studies students chose to perform self-ethnographies of their new experimentations, others decided to observe different drone communities at work. Their studies took them in unexpected directions, exploring the labor of extreme drone photography in Australia, drone enthusiast summits (International Drone Day at the Vaughn College of Aeronautics and Technology in Queens, New York), the use of drones as dancing partners (for example, the work of Japanese dance company Elevenplay) or as painting devices (as in the work of Addie Wagenknecht). Students contemplated on a new field of aerial visuality opened by drones, pondering whether there is more potential in it than simply the “masculinist drive to see from on top.” (Feigenbaum 2015) They observed how urban explorers were using drones and the challenge faced by startups to change consumers’ mental image of drones. Throughout our research, our understanding of the drone has fluctuated from that of a threatening creature to a domesticated companion with a full range of DNA potentiality; some students saw a persona of intimacy in the drone, while for others cynicism and malicious instincts loomed dangerously over the belief in drones acting as humanitarian aid.

“Dressing Your Drone.” An exploration in technotherapy for reluctant drone users in anticipation of a future where drones will be more prevalent in everyday life. Handmade miniature drone outfits, meant to be fastened on with Velcro much like dressing a Barbie Doll, develop an intimate relationship between user and technology and a certain degree of absurdity bringing humor into the equation in hopes of assuaging technophobic feelings. Project by MA Design Studies student Claudia Marina. Photograph by Claudia Marina.

Between technophobia and technophilia, embodiment and disembodiment, belief in their humanitarian potential and skepticism due to inescapable geopolitical asymmetries, drones demand from us to reposition ourselves in the world from ethical, political, and physical perspectives. Societies always co-evolve around emerging technologies, and individuals and groups are required to constantly reflect on their position about drones, their manufacturing, their purpose, and their alliances.

Whether we embrace them, fear them, or fight with or for them is our choice. But as design thinkers and citizens, we should reflect on what we sacrifice with every step toward new technology that substitutes or expands our possibilities. We should become aware that what seems like a humane or collective goal does not always unite us, and that there are always multiple publics that are being generated every time a new system or artifact comes into the world. Agency, constitutional rights, and ethical principles are not just granted or afforded, but gained.

References

Feigenbaum, Anna. “From Cyborg Feminism to Drone Feminism: Remembering Women’s Anti-Nuclear Activisms.” Feminist Theory 16/3 (2015): 265-288.

Asaro, Peter. “The Labor of Surveillance and Bureaucratized Killing: New Subjectivities of Military Drone Operators.” Social Semiotics 23/2 (2013): 196–224.

Sandvik, Kristin Bergtora and Kjersti Lohne. “The Rise of the Humanitarian Drone: Giving Content to an Emerging Concept,” Millennium – Journal of International Studies 43 (2014): 145-164.