Leaning In: The Importance of Sociomaterial Interaction at the Brooklyn Public Library

Zishan Jiwani

A recent ethnographic investigation by Parsons School of Design at the Bedford branch of the Brooklyn Public Library (BPL) drew this bold conclusion: “It’s clearly evident that Bedford branch staff go well beyond their job descriptions to help patrons.”1 The report generated from the research details stories of meaningful relationships and community-focused initiatives observed at the library. Bedford’s approach aligns with BPL’s 2018 Strategic Plan which emphasizes that “everyone is welcome”2 and advocates building “a relationships-based service model.3 Library staff are asked to do more than just stock and checkout materials; they are tasked with prioritizing their engagement with residents to develop trusting relationships that are not merely transactional.4

To deepen my understanding of relationships at Bedford, I observed the patron-staff interactions at the front desk of the library and subsequently at two other branches (Marcy and DeKalb). In my research, I focused on the quality of the “welcome.” In what ways is the “welcome” about providing quick and efficient service while also encapsulating the more complex work of building and maintaining trusting relationships?5 Expecting the research to show a range of relationships, I took note of the time spent by patrons at the front desk, as well as the gestures characterizing the interactions that may be formative in the emergence and maintenance of relational library space. In the observations, the structure and materiality of the front desk itself emerged as a critical player in both facilitating and disrupting conversation, comfort, and connection. An experiment at the Bedford branch indicated how small changes in the presentation of the front desk could radically alter how relationality emerged at the front desk and, potentially, the library at large.

The Evolving Front Desk

The choice of the front desk as the point of observation was intentional, given its centrality in patron-staff interactions. The Brooklyn Public Library Design Guidelines describe the front desk “as the core of the branch library and its most important interior design and program feature.”6 Despite its prominence, or maybe because of it, the role and design of the front desk (also referred to as the service desk, circulation desk, or reference desk) has been hotly debated since the Carnegie era.7 The front desks in many Carnegie-era library branches, including Bedford (Fig. 1) and DeKalb, tend to be large, imposing, and impenetrable, perhaps attempting to physically embody the perceived command and control of librarians vis-a-vis the patrons.8 Yet, as the purpose and value of libraries have radically shifted in the era of techno-capitalism, the role and perception of the front desk has also shifted.

Figure 1. Front desk of Brooklyn Public Library Bedford Branch. John Bruce and Pawel Wojtasik, Brooklyn, New York, 2019.

Conversations with members of the capital management team at the Brooklyn Public Library and a review of the Brooklyn Public Library Design Guidelines reveal a few general principles and priorities in front desk design. First and foremost is visibility—the front desk must be visible as soon as a patron enters the library and there must be maximum visibility from the front desk to the rest of the library. A second important principle is to reduce front desk size to maximize patron floor space. Another reason for the reduction of desk sizes may be to prevent librarians from “cocooning” behind desks while reactively waiting for patrons to take the initiative to approach and ask questions.9 Finally, the ubiquity of technology plays a critical role in modern front desk designs as designers are asked to ensure that monitors facilitate, rather than impede, patron-staff interaction.10

While there is quite a bit of effort and thought being put into front desk designs at libraries across the country,11 a question emerged as to what extent the front desk is understood as an actor in enhancing what BPL calls a “relationships-based service model.”12 While not succumbing to material determinism, are there ways to enable relationality at the front desk while maintaining the priority of a safe space for librarians? How might other models reconfigure affordances for connection? Can a library more closely resemble the model for interaction used at the Apple Store, with roving librarians with headsets serving patrons with a cheery, “Can I help you find something?”13 This essay provides insights from my research to better understand active modes of welcoming at a public library.

Relational Observation: Methodology of Sociomaterial Research

I conducted and framed this research with an emphasis on sociomateriality. The sociomaterial view grounds itself in relationality and attempts to move away from the notion that material or human can be understood separately.14 Human and material interaction is not seen as pre-formed or pre-designed. Sociomaterial research invites an entangled and complex perspective where reality is seen as an ensemble of performative interactions between the social and material.15 As such, even as a researcher, I see myself not as an objective onlooker of the phenomenon but rather deeply entangled in the process and in the lives of those I am attempting to observe. This is especially true at Bedford where the staff knew that I was observing them and even suggested the best vantage point. As such, I also apply an autoethnographic approach in the research where I place myself in the social and aesthetic context of the library.16 I observed my gestures, comfort, and emerging relationality during the informal interviews with staff which happened almost exclusively at the front desk.

As an observer, my perspective was always limited. I occupied a different vantage point at each of the libraries. At Bedford, I sat on a higher floor with a full view of the front desk from the rear. At the Marcy and DeKalb branches, I was located to the side of the front desk and my view was a bit obscured. While I could see much of the interactions between patrons and staff, I was not in clear hearing range at any of the libraries. Following in the footsteps of the ethnographer Christena Nippert-Eng, I committed myself to a systematic observation rather than an open-ended one.17 For each patron-staff interaction, I noted the time the interaction began and ended, along with a description of the patron and the gestures that occurred during the interaction. When I could hear parts of the conversation, I also noted the greetings and other shared dialogue. Initially, I employed a notebook, but I switched to Google Sheets, as it was much easier to record the data. I also used my field notes to record my own reflections that emerged throughout the process and have used those notes as additional data when analyzing my findings.

When I began my observations, I did not intend to focus on the materiality of the front desk. However, throughout my observations, the desk revealed itself as a critical player in patron-staff interaction. In this section, I present the observational data and some reflections for each of the libraries and encourage readers to make their own interpretations before presenting my analysis. The data shared here is a result of front desk observations lasting from one to three hours at three branch libraries. One limitation of the study is that I only conducted observations on one occasion at each of the three libraries thus limiting the generalizability of the findings from the research.

Bedford

An old Carnegie-era desk, Bedford’s desk is an ostentatious high table with a large flat surface area. The staff typically sit on a tall chair or stool. I observed forty patron-staff interactions from 1:00 p.m. to 4:00 p.m. on a cold Wednesday afternoon. These interactions lasted anywhere from two seconds to nearly a half hour with the median time spent around two minutes. Thirty percent of the interactions lasted more than two minutes.

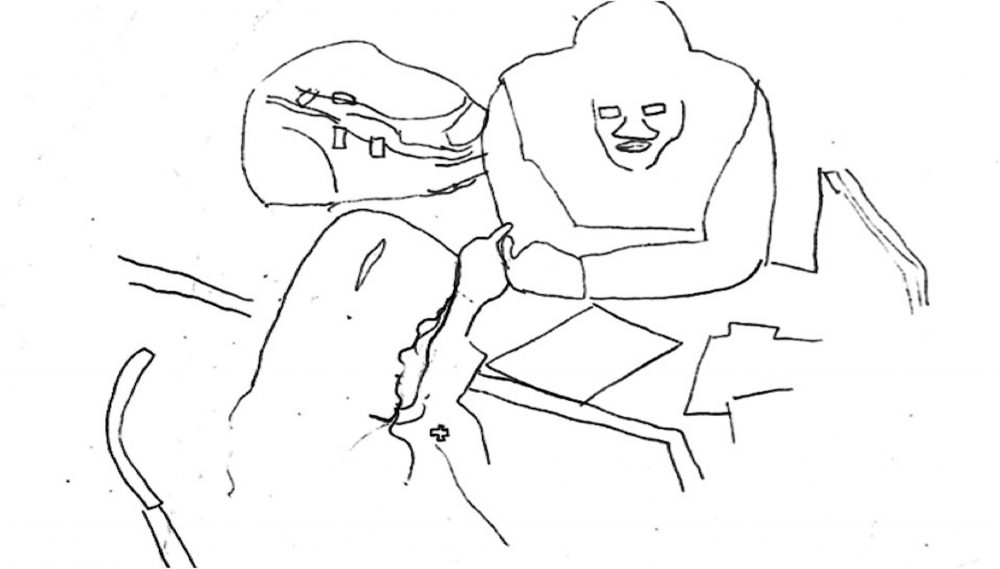

The broad surface area of the desk allowed patrons to put down their large backpacks or handbags and use the desk to lean in. Of the 40 interactions I observed over a three-hour period, half of them involved some sort of leaning gestures, especially if they stayed at the desk for more than two minutes. Some patrons had a slight lean where their lower body hugged the desk, their upper bodies upright with their hands lightly placed on top of the desk as a momentary place for rest. Others embodied more defined leaning over whereby their upper body hovered on the desk as their forearms provided support (Fig. 2). In most cases, those leaning tended to stay longer and have collaborative interaction. These collaborative interactions included simple gestures like working together on a laptop or phone. Other gestures I noticed at the desk included laughter and firm handshakes along with statements of greetings and appreciation, such as “What’s going on, man?” and “I appreciate you, man.”

Having tried this lean myself, I found it comfortable enough to contentedly stand in place for some time. I also noticed and appreciated the ability to hold direct eye contact with the staff member, allowing us to speak directly to each other. I noticed the intimacy of the space but also the distance and separation.

Figure 2. Sketch of a patron leaning in on the Brooklyn Public Library Bedford Branch front desk. Ayushi Jain and Zishan Jiwani, Brooklyn, New York, 2019.

Marcy

In contrast to the front desks at the Bedford and DeKalb branches, the front desk at the Marcy branch (Fig. 3) faces a side wall rather than the front entrance. The desk resembles a style more typical of the service industry where the staff sits at a lower level in normal office chairs. A part of the table was a bit higher than the rest, but much of it was covered with event and policy notices on tabletop flyer-holders. In a two-hour period on a late Saturday morning, I observed 19 interactions lasting between 11 seconds and 47 minutes. The median time was about 40 seconds. Ten percent of the interactions lasted more than five minutes.

The interactions were generally straightforward and polite. When a patron needed assistance, they were generally served promptly. Many patrons offered a “hi” when they approached, proceeded to ask for what they needed, and then went about their day. The one anomaly was the 47-minute interaction that happened largely behind the desk where the patron was invited to sit with the librarian so that she could offer assistance. In my follow-up conversation with the librarian, she mentioned that she is very careful in determining who she invites behind the desk. This particular patron was a regular, and they had built a trusting relationship before she felt comfortable extending this invitation. Since the invitation had not been extended to me, I kept changing my posture to try to hold an eye-level interaction with the librarian as the structure of the desk did not allow for it very easily. I initially bent my knees into a near squatting position so I could engage in an eye-level conversation which was not very comfortable, and so eventually, I found a place to lean against the side of the desk where we continued to speak for a few minutes. In this posture, I was looking down at the librarian and found the leaning less comfortable in part because I worried about imposing (physically and metaphorically).

Figure 3. Sketch of the front desk at the Brooklyn Public Library Marcy Branch. Ayushi Jain and Zishan Jiwani, Brooklyn, New York, 2019.

DeKalb

DeKalb’s front desk (Fig. 4) is closer to the front door and occupies a much larger space than those at Marcy or Bedford. The ornate desk features lower seating for staff, but the desk design does offer a small space for patrons to put down their belongings and potentially lean in. Much of the desk space was covered in plastic sign holders containing a variety of notices. In my hour of observation on a Wednesday evening, I observed 18 interactions lasting between 12 seconds and nearly five minutes. No interactions exceeded five minutes, which may be because the library was busier than usual. In four instances, I observed some leaning. Three patrons clearly leaned over the desk, and the fourth in a slighter lean. Similar to Bedford, these interactions lasted longer than the median interactions.

My interaction at the DeKalb library was brief, as the librarian was unsure about whether she could speak with me without explicit permission. While speaking with her, I found one palm cupping my face, being supported by my elbow, which was leaning on the desk beside my other forearm.

Figure 4. Figure 4.Sketch of the front desk at the Brooklyn Public Library DeKalb Branch. Ayushi Jain and Zishan Jiwani, Brooklyn, New York, 2019.

An Experiment

According to the data, the patrons who leaned on the front desk were more likely to spend time engaged in convivial conversation. For example, one of the patrons who needed a library card ended up leaning in on the desk, engaged in simple banter resulted in shared laughter between her and the assisting staff member. Even in my own experience, leaning in created a sense of pause, in a way that standing straight in front of a desk did not. When I asked the Bedford

Library staff about this observation, they said that they had never thought about the role of the desk in shaping interactions but agreed that it likely plays a role. One staff member stated that he would bring up the role of the desk in the next library staff meeting. However, the front desk staff and I were curious to check our hypothesis, so we conducted a simple experiment. For a little over an hour on a Wednesday afternoon, we covered the Bedford desk with sign holders. The median time in the 18 observed interactions was 26 seconds, as compared to the two minutes without the sign holders. Many patrons seemed to want to lean but could not fully manage because the blocked access (Fig. 5). As such, I noticed several partial leans where patrons leaned with just one arm. One particular patron, desperate to find a comfortable position, began leaning in with one arm and then switched to the other after a few moments before switching again.

The other unexpected finding from this experiment was that the paper signs seemed to create a wall separating staff from the patrons and the rest of the library. The staff members later confirmed that the sign holders made them feel more immersed in their tasks behind the desk. I noticed one librarian deeply engrossed in reading the newspaper, not looking up when patrons entered or exited the library, which was unusual based on previous observations.

Figure 5. Sketch of the Brooklyn Public Library Bedford Branch front desk during the provocation. Ayushi Jain and Zishan Jiwani, Brooklyn, New York, 2019.

Balancing Relationality and Safety

As the place of the library in contemporary society shifts, the role of the librarian is similarly evolving. In The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, Erving Goffman says, “When an individual plays a part, he implicitly requests his observers to take seriously the impression that is fostered before them.”18 Sitting behind the front desk, the librarian performs the role of the expert able to guide patrons in locating and checking out books, obtaining library cards, using computers, writing resumes, providing legal advice, and fixing technical problems on laptops. Simultaneously, there are other parts that librarians are playing (and being asked to play) that are critical in meeting or surpassing the needs of the communities they serve. Denise, a library staff member at Bedford, shared that she feels her role at the front desk is sometimes one of a neighborhood therapist. On the day that I was observing interactions at the desk, Denise had a nearly 30-minute conversation with a patron. According to Denise, they spoke about anything and everything. Elaine, also at Bedford, refers to herself as the “library mother.”19 She shared that people come to the library because they just need to have a conversation—something that easily and normally takes place at the front desk.

As the design, placement, and arrangement of the front desk mediates the relationship between the library staff and visitors, it influences the ease at which librarians can perform their duties. In an earlier era, the front desk design served as a physical marker for control and embodied the oppositional nature of the relationship between the patrons and librarians.20 Even as the Brooklyn Public Library moves toward a relationship-based service model, the desk is still seen as a primarily functional rather than social object. Consideration of how the design of the desk facilitates or stifles relationships cannot be ignored. I observed this fact at the Marcy branch, where the low desk only allowed one patron to engage in an extended conversation with the librarian. Librarians instead had to invite the patron behind the desk thus circumventing the structure entirely. Conversely, at Bedford, I observed multiple patrons engaged in long conversations while leaning on the desk. However, as observed during the experiment above, design alone is not sufficient. The set-up of the desk is also crucial, as it is very easy to prevent relationship-building conversations when the desk is filled with paper sign holders that hide librarians behind the desk to avoid engaging in the kind of relationship-building conversations necessary to fulfill the library’s objectives.

There is something very different about a relationship-building conversation relative to one that is purely transactional. A transactional conversation focuses on completing a task or meeting a need (e.g. a broken printer, needing a new library card, etc.) Witnessing these conversations, I noticed a tightening in the shoulders and a need for urgency to move on. There is a different air about a relationship-building conversation. At DeKalb Library (when my observation sense got a bit keener), it was very easy to tell the difference between these types of conversations from simply observing bodies. In a relationship-building conversation, I noticed an evident drop in the tension. This was observed by the librarian leaning back in her chair, hands resting lightly on her lap. There were more smiles, no sense of hurry, and no move to a quick and “efficient” resolution or provision of service. An important commitment of the Brooklyn Public Library is expressed in their maxim: “Everyone is welcome here.”21 Yet, there is a question as to what “welcome” feels like. Is it a feeling of tolerance or one of hospitality? The act of leaning, signifying a moment of rest, comfort, and safety for those who enter the library, points to the spectrum of interactions that occur in the library and the quality of the relationships between those who work there and for the patrons.

Yet when library staff expose themselves through unconditional welcoming, questions around safety are made evident. “Everyone” is not easy to welcome. Two librarians brought up the fear of physical safety. One female librarian at Bedford spoke about sometimes wanting a glass partition at the desk as patrons occasionally get very close, creating feelings of discomfort and risk. A librarian at the Marcy branch shared that there have been instances where she has feared for her physical safety. The desk provides some distance and separation between patrons and staff which may facilitate a sense of safety. The desk may also provide a sense of safety from the eroding professional identity of the librarian. The desk is the space where a librarian enacts or performs her professional identity, providing a sense of control.22 Moving toward a smaller desk or no desk at all might compromise the sense of safety and control that emerges from being behind a desk.

Conclusion

In seeking to understand how relationships are built at public libraries, this research attempts to make visible the role of the design of the front desk in enabling longer and more convivial social interactions. Through observations at three branch libraries and the experiment at Bedford, it was clear how the ability to lean on the desk played a critical role in determining the amount of time patrons spend at the desk and the quality of their interactions with staff. The role of the desk in creating a sense of safety for the library staff also emerged as an important consideration in front desk design moving forward. Although the findings here are limited, they provide insights that further research could elaborate on developing a deeper understanding of how the design of the front desk matters in welcoming the public and establishing conviviality central to a rich and diverse social infrastructure.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my deep gratitude to Barbara Adams, Shannon Mattern, John Bruce, and John Hanson for their comments and support provided throughout this project. I also immensely appreciate the assistance and tutorials from Ayushi Jain on the sketches. I also want to thank Hannah Rose Fox for her support and partnership during the observations. Finally, I am most grateful for the staff at Bedford, DeKalb, and Marcy branches as well as the Capital Management team at the Brooklyn Public Library for the conversations and the incredible work they do every day.

Endnotes

1. Brooklyn Public Library and Parsons DESIS Lab, Libraries as Sites for Transformative Justice, New York: The New School, 2019.↵

2. Leigh Hurwitz and Kat Savage, “Profoundly Out,” interview by David Giles, Brooklyn Public Library, October 2018, https://www.bklynlibrary.org/strategicplan/spotlights?spot=spot-profoundly-out.↵

3. “Strategic Plan 2018,” Brooklyn Public Library, https://www.bklynlibrary.org/strategicplan/report.↵

4. Ibid.↵

5. Laura Penin, Eduardo Staszowski, John Bruce, Barbara Adams, and Mariana Amatullo, “Public Libraries as Engines of Democracy: A Research and 282 Pedagogical Case Study on Designing for Re-Entry,” paper presented at the Nordes Conference: Who Cares?, Espoo, Finland, June 2019.↵

6. Louise Harpman, Brooklyn Public Library Design Guidelines, City of New York Department of Design and Construction with The Brooklyn Public Library (July 1996), http://designtrust.org/projects/BPL-design-guidelines/.↵

7. Shannon Mattern, The New Downtown Library: Designing with Communities (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007), 130.↵

8. Ibid, 134.↵

9. Ibid, 133.↵

10. Harpman, Brooklyn Public Library Design Guidelines.↵

11. Raymond M. Holt, “Trends in Public Library Buildings,” Library Trends (Fall 1987): 267–85.↵

12. “Strategic Plan 2018.”↵

13. Mattern, The New Downtown Library, 125.↵

14. Lotta Hultin, “On Becoming a Sociomaterial Researcher: Exploring Epistemological Practices Grounded in a Relational, Performative Ontology,” Information and Organization 29, no. 2 (June 2019): 91.↵

15. See Hulin and Karen Barad, Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning (Duke University Press, 2007).↵

16. Shahram Khosravi, ‘Illegal’ Traveller: An Auto-Ethnography of Borders (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010).↵

17. Christena Nippert-Eng, Watching Closely: A Guide to Ethnographic Observation (Oxford University Press, 2015).↵

18. Erving Goffman, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life (Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company, 1959),10.↵

19. John Bruce and Pawel Wojtasik, Elaine, Parsons DESIS Lab, 2018, https://vimeo.com/314357232.↵

20. Mattern, The New Downtown Library, 130.↵

21. Hurwitz and Savage, “Profoundly Out.”↵

22. Mattern, The New Downtown Library, 134.↵

Author Affiliations

Zishan Jiwani is a graduate student in the Transdisciplinary Design program at Parsons School of Design and the Psychology program at the New School for Social Research.

DESIGN STUDIES BLOG

DESIGN STUDIES BLOG