An Elusive Viewshed: An Investigation of United States’ Border Patrol Rescue Beacons in Arizona’s Western Desert

Tara Plath

At the end of a 40-minute drive down a rugged, twisting dirt road near the small unincorporated community of Ajo, Arizona, stands a curious piece of technology. Called a rescue beacon, and sometimes referred to as a “Panic Pole,” there are fifty such objects strewn across Arizona’s western desert, installed and maintained by the United States Border Patrol.1 They are intended to be seen by undocumented migrants crossing through these remote areas of Arizona. While seemingly innocuous, these beacons have come under increased scrutiny in recent years as Border Patrol has expanded its surveillance and criminalization of humanitarian workers in the area. Through their monopolization surrounding the rhetoric of aid and rescue, Border Patrol claims the beacons are an adequate response to the deaths and disappearances of thousands of undocumented people crossing the border outside of state-sanctioned channels. In Arizona, beacons are installed primarily on federally-managed land in the arid Sonoran Desert. Much of this area is not the flat, sandy picture of the desert imaginary but rather a craggy, mountainous landscape, coated in loose stones carried by storm waters and abundant thorny flora, such as the jumping cholla and the saguaro cactus, making each step hazardous.

While the beacon’s design varies by Border Patrol Sector and state, this one consists of a slender steel mast standing ten meters tall, secured by a five-foot square cement base. Various devices are secured to the mast. At eye-level rests a large box, laminated with pictographs and instructions in English, Spanish, and Tohono O’odham—the language of the indigenous peoples whose ancestral lands the object stands on—with a weather-worn red button bottom center. Further up, a discreet motion-activated camera is installed just below a solar panel that faces the glaring sun at an angle. Atop the pole, a piece of twisted mirrored metal spins and powerful blue LED lights strobe in 10-second intervals. The written instructions direct those who encounter the beacon and require aid to press the button and wait in place for up to an hour for aid to arrive. (Fig. 1, 2)

Figure 1. A Border Patrol Rescue Beacon installed on the Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument in Arizona, which shares its southern boundary with the US-Mexico border. Tara Plath, Arizona, 2019.

Figure 2. Spinning reflective metal and a strobing blue LED light are design features intended to make the Rescue Beacons visible for up to a ten mile radius. Tara Plath, Arizona, 2019.

A beacon is conventionally understood as “a fire or light set up in a high or prominent position as a warning, signal, or celebration.”2 It is intended to illuminate, communicate, direct, and dictate a course of action. Recognition of a beacon’s signal depends upon a relationship between the object’s design and its intended receiver. A beacon’s foremost goal is to first be detected from a distance, then recognized for its intended message.3 To understand the Border Patrol Rescue Beacon as a form of communication, it is necessary to have a sense of how and what it communicates. Such fundamental questions are not easily answered in the case of the Border Patrol Rescue Beacon and point to the challenges of researching transnational movement outside of state-sanctioned channels and the deportation regime, which are, by design, difficult to penetrate. While the rescue beacons are cited by the Border Patrol’s legal representation as the preferred method of saving lives in the Arizona-Sonora borderlands, data regarding their effectiveness and even their exact locations are withheld or revealed in piecemeal.

The rescue beacons are a distillation, in form and function, of Border Patrol’s response to what humanitarian organization No More Deaths/No Más Muertes describes as a “crisis of death and disappearance” in Arizona’s western desert.4 Though they are often couched in the rhetoric of aid and humanitarianism by Border Patrol and the media, the rescue beacons operate as a supplemental technology of the border regime, within a system of ceaseless “‘crisis’ management” in a scenario characterized by the US government and media as a “border out of control.”5 This human rights catastrophe, which has claimed the lives of untold thousands, is the result of the implementation of 1994’s Southwest Border Strategy, a pivotal shift in border enforcement that expanded personnel and infrastructure in cities along the Southwest border.

As has been analyzed extensively by scholarship on the subject, this policy shift fell under the rubric of a strategy coined “prevention through deterrence,” which sought to create an environment of elevated risks and additional obstacles to crossing the border using traditional routes through border cities.6 Such deterrents include an increased threat of apprehension by Border Patrol agents, a projected rise in smuggling fees, and the forceful re-routing of traditional migration routes out of urban environments such as El Paso and San Diego and across “more hostile terrain, less suited for crossing and more suited for enforcement.”7 It was believed these factors together would, in turn, deter any clandestine attempt to cross the border, resulting in an overall decrease in attempts.8 The shift into hostile terrain did occur as predicted but was promptly followed by a severe increase in the documentation of border-crossing fatalities,9 which shifted dramatically from vehicle-related accidents in the ’90s to exposure and dehydration in the mountainous terrain of the Arizona-Sonora Desert since the early 2000s. Much of this land, where the beacons are now located, is managed by the federal government.10

Rescue beacons were first implemented in the early aughts as part of the Border Safety Initiative (BSI) program, a communications strategy launched by Customs and Border Protection in 1998 in response to the growing number of border crossing-related fatalities. BSI was developed “to educate and inform potential migrants of the dangers and hazards of crossing the border illegally,” as a sort of communications strategy that employed

warning signs in high-risk areas; border safety awareness campaigns; public service announcements on television and radio; emergency medical technician training for agents; and rescue beacons […]11

As one aspect of the BSI campaign, the rescue beacon can be understood as a technology of communication in its literal and figurative functions alike, which demands that we interrogate both what they reveal and obscure. The beacons are suffused with contradiction. While they operate as part of the “border spectacle,” a process that “renders a racialized migrant ‘illegality’ visible,” they also function as a tool of obfuscation, by selectively reframing the figure of the undocumented migrant from “criminal” to “hapless victim” to divert criticism aimed at Border Patrol’s enforcement tactics, using the beacon as evidence of the agency’s invested interest in saving lives.12 While the beacons seek to draw attention to those in need of medical attention, they simultaneously perform the work of detecting and deporting those moving outside of state channels. All the while, the beacons illuminate the contours of the “discursive limits of intelligibility”13 of violence against undocumented migrants crossing the harsh desert borderlands, which has not gone entirely unseen or unnoticed but remains perpetually under-articulated within the hegemonic public discourse of citizenship and deservedness.14

The following analysis is the result of a year-long investigation, conducted in coordination with local humanitarian aid workers and activists, to better understand how these objects function across rhetorical, humanitarian, and securitization registers. An analysis of various reports, data sets, court documents, Congressional records, and related media is complemented by interviews with medical professionals, humanitarian aid workers, and Border Patrol agents. Freedom of Information Act requests and remote sensing techniques were employed using open source satellite services to geolocate more than forty beacons in the state of Arizona.15 Additional fieldwork in southern Arizona further informed the research, providing a first-hand view of the environmental conditions, the politics of land access, and the efforts of humanitarian volunteers.

Mobile Technologies: Rescue Beacons and Humanitarian Border

There has been much scholarship regarding the concept of a humanitarian government, which Didier Fassin describes as “the administration of human collectivities in the name of a higher moral principle which sees the preservation of life and the alleviation of suffering as the highest value of action.”15 This concept is not contained within the actions and intentions of the binary figures of state and nonstate entities. Rather, “it creates competition between them as governmental policymakers more and more frequently contest non-governmental organizations’ claim to a monopoly on the concept.”16 By adopting the rhetoric and appropriating the practices of non-governmental humanitarian organizations, state powers aim to maintain a firm grip on the established sovereign order that these other entities might seek to challenge in the name of universal human rights.

In line with Fassin’s framework of the pervasive logic of humanitarian reason,17 the rescue beacon can be interpreted as representing a collapse of humanitarian and securitization practices within the US border regime. This collapse is the material manifestation of what feminist geographer Jill Williams calls the “safety/security nexus,” through which “migrant safety and border security are seemingly reconciled in both official state discourse and policy.”18 Through the rescue beacon, Border Patrol mobilizes humanitarian reason to advance its goals of apprehension and deportation, as well as to further establish its predominant presence on federal conservation lands as a challenge to intervention by non-governmental actors.19

Through the BSI campaign’s unilateral communicative strategy, Border Patrol reduces the narrative of border crossing to be understood as solely the criminal actions of individuals unaware of the dangers that await them, along with the actions of “unscrupulous smugglers.”20 This narrow interpretation of the complex conditions that produced thousands of deaths in southern Arizona allows Border Patrol to portray itself as an altruistic operation that seeks to end fatalities by first ending illicit crossings, an endeavor that has long been accepted as impossible by immigration experts and Border Patrol itself.21 This formulation not only glosses over the fact that the observable trend of increased border-crossing deaths can be directly attributed to policy decisions intentionally designed to shift cross-border routes into the desert, but it also reorganizes the state’s relationship to its obligation to the health and well-being of the undocumented on US territory. As Marina Kaneti and Mariana Assis have articulated, campaigns under BSI do not

invoke either the state deterrence strategies and enforcement capabilities or the tremendous mobility and technological capacity of the sovereign state. To the contrary, by minimizing the presence of the state, the campaigns shift attention away from the (failed) politics of border control onto a spatial framing that is seemingly beyond or outside the parameters of sovereign state territories.22

These parameters encompass Border Patrol’s insistence on its limited capacity to adequately respond to the proliferation of deaths and disappearances within its jurisdiction, but also the agency’s refusal to acknowledge any obligation to do so. As Williams surmises, humanitarian aspects of border enforcement are not the product of an obligation to upholding human rights, but rather are recast by the government as a benevolent gesture above state responsibility.23 The beacon’s position in this space of excess relies on an assumption of the undocumented as undeserving of a set of internationally-recognized human rights reserved for citizens within the “territorialized framework of sovereignty.”24 Relegated to the realm of morals, the beacons are guarded against scrutiny and appropriated into the project of securitization. This formulation explains why the rescue beacons have never been subjected to thorough quantitative analysis nor rigorously examined for evidence of efficacy.

One can better understand how these objects, emblematic of William Walters’ concept of the “humanitarian border,” function as a tool of territorialization.25 This is shown in their ability to move according to the shifting patterns of transnational routes and through the expansive nature of their estimated viewshed. Additionally, they work by displacing the presence of humanitarian aid workers and activists who, in addition to their medical interventions and supply drops in the desert, bear witness and draw attention to the realities of border enforcement in Arizona’s most remote areas. (Fig. 3)

Figure 3. Volunteers with humanitarian organizations No More Deaths and Los Armadillos record the location of human remains in the Growler Valley, Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge, found while conducting a coordinated Search and Rescue mission. Tara Plath, Arizona, 2019.

This is perhaps seen most clearly in the legal actions taken by Border Patrol against local humanitarian aid organizations, primarily No More Deaths. Over two days in May 2019, the organization discovered four sets of human remains in the Growler Valley, an expanse of rugged desert between mountain ranges on the Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge, west of Ajo. The search and rescue mission had been precipitated by a call to No More Deaths’ Missing Migrant Hotline from a family member of someone believed to have disappeared in this area. According to a press release issued by No More Deaths, the family had turned to the organization’s hotline after Border Patrol had refused to deploy a coordinated rescue effort.26

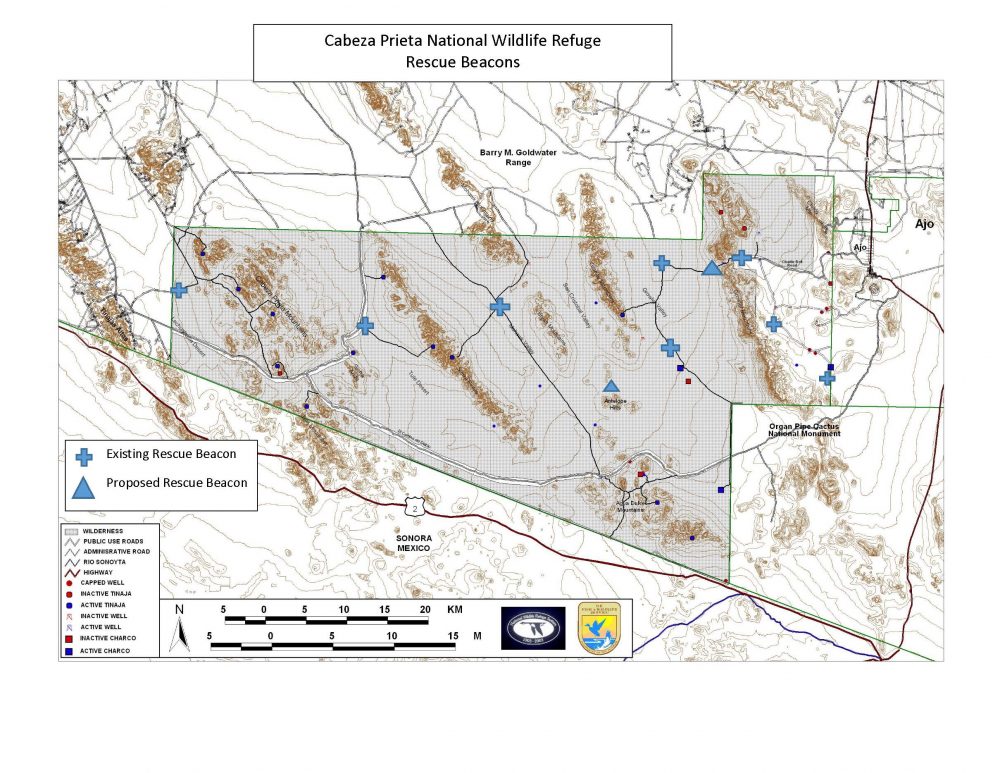

These grim discoveries coincided with the first day of legal proceedings of charges brought by the US government against No More Deaths’ long-standing volunteer Scott Warren. During the trial against Warren, federal prosecutor Anna Wright argued that “humanitarian aid should be left to the Border Patrol,” in reference to the rescue beacons on the Cabeza Prieta.27 The thirteen beacons that stand on or directly adjacent to the refuge play an active part in the territorialization of conservation land, as they become the locus of negotiation between Cabeza Prieta’s manager Sid Slone, Border Patrol, and humanitarian groups.28 The beacons are mobilized concurrent to permitting processes that allow the refuge to keep track of who is on refuge lands and for what purpose, selective enforcement of refuge protocols, and increased surveillance. As No More Deaths actively criticizes Border Patrol tactics by publishing detailed reports of various abuses, these restrictions serve to limit exposure, access, and the potential for intervention within the perpetual state of disappearance on Cabeza Prieta and the surrounding areas.

A US Fish and Wildlife Service Environmental Action Statement For Categorical Exclusion published on the homepage of Cabeza Prieta’s website in May of 2018 describes the impetus and protocol for relocating some beacons as well as deploying additional beacons within the refuge that would

cover areas that receive significant CBV [Cross Border Violator] traffic and have received mortalities in the recent past. Under the proposed action, rescue beacons could be re-deployed from areas where they receive little to no activity to higher need locations as mutually determined by the Refuge and CBP [Customs and Border Protection] in response to CBV activity and deaths. This will allow the Refuge and CBP flexibility to move and temporary [sic] place rescue beacons where they will be the most effective in saving lives.29

Lisa Meierotto describes in detail how this same federally designated wilderness area has been perpetually entangled with the militarization of the border. Recounting the concurrent histories of the Cabeza Prieta alongside increased militarization in Arizona, Meierotto points to friction between the missions of both conservation groups and the Department of Homeland Security. One example includes public opposition and tentative objections on the part of the refuge’s management in response to a 2008 proposal to install permanent surveillance towers on the Cabeza Prieta. A 2010 statement from the refuge manager at the time cited Section 4(c) of the Wilderness Act of 1964, detailing the prohibition of “the placement of any type of permanent infrastructure in wilderness, except as necessary to meet minimum requirements for the administration of the area for the purpose of the Wilderness,” deeming the towers incompatible with the refuge’s mandate.30

No such objection is found with the rescue beacon, which qualified for an indefinite categorical exclusion in 2006 following an environmental assessment that claimed the installation and maintenance of the beacons caused “no significant impact” to the ecologically sensitive area.31 The rescue beacon’s small footprint and mobile design, as well as its stated humanitarian purpose, allows for Border Patrol to extend its surveillance and apprehension apparatus further onto conservation lands in the form of a humanitarian border, whose “geography is determined in part by the shifting routes of migrants themselves.”32 (Fig. 4)

Figure 4. Undated map produced by the Fish and Wildlife Service identifying existing Rescue Beacons and proposed locations for new beacons. Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge Rescue Beacons, Fish and Wildlife Service, date unknown. (Obtained by the author under the Freedom of Information Act from US Department of the Interior; requested March 6th, 2019; received October 24th, 2019).

Mixed Signals: Detection, Recognition, Apprehension

The Environmental Action Statement for Categorical Exclusion specifies the need to intermittently relocate beacons, as needed:

As [Cross-Border Violators] activity decreases in some areas and the rescue beacon becomes less used, or even unused, it is logical to move the rescue beacon to a location where they will provide the most benefit of saving lives.33

What is not accounted for in such a formulation is the possibility that the beacons might actively push these routes through more dangerous terrain if they are perceived not as a point of aid but rather as a threat of deportation.

Rescue beacons are built in-house by Border Patrol agents in the design and manufacturing department. They are constructed with various parts according to their design specifications, which can vary across Border Patrol sectors and states. For daytime visibility, mirrored metal is secured to the top of the beacon’s pole, in the hopes that it will reflect light from the sun in such a fashion that will catch the eye of someone on the ground. For evening visibility, blue LED lights are arranged with an omnidirectional projection of roughly 130 degrees and strobe in ten-second intervals. Border Patrol publicly states that the LED lights allow for optimal visibility for up to ten miles. This is corroborated by the testimony of those who live and drive in the surrounding area.34 However, this number does not give Border Patrol’s Tucson Sector “340 miles of visibility” as described by reporting on the beacons.35 That number hardly appropriately relates to the challenges of crossing the desert on foot.36

The following 911 call from someone in distress was forwarded directly to Border Patrol. This excerpt reveals that if the blue light of a beacon is identified, it may not signal any significance until Border Patrol operators encourage the caller to walk to the beacon to verify the caller’s exact location:

Caller: Now I see a blue light.

Border Patrol: You see a blue light?

Caller: Yes, that keeps going out.

Border Patrol: Look . . . go to it and press the button.

Caller: No, the light is too far from where I am.37

There are also numerous examples of human remains attributed to migrants discovered in relatively close distance (within a mile) of the beacons.38 There are innumerable reasons for why this might be, but it can be assumed that while a beacon can be first detected and recognized, the challenges of reaching a beacon even one mile away can be insurmountable to someone malnourished, dehydrated, and suffering of exposure to the harsh elements of the Sonoran Desert, as the caller in this example makes clear.

A study conducted by Samuel Norton Chambers, Geoffrey Alan Boyce, and Sarah Launius describes the tertiary funnel effect of surveillance towers in the Arizona-Sonora borderlands, which further amplifies the already-violent consequences of shifting routes into remote terrain between urban centers by pushing migrants even further into “hostile terrain” between visible surveillance towers that the undocumented seek to avoid. Through a spatial analysis that compared the coordinates of recovered human remains before and after the installation of integrated fixed towers in Arizona’s Altar Valley, the study affirmed that visible surveillance infrastructure forces migrants to shift their routes into more dangerous and remote areas, increasing the risk of harm or death. It is not unfounded that extending this logic to the rescue beacons would yield similar results.39

While blue lights are often used to signal emergency or alarm within an American context, there is no clear evidence that the choice of blue light was made with any sensitivity toward designing a visual indicator of aid. Rather, Border Patrol’s choice of the color blue was to avoid disrupting the endangered Sonoran pronghorn antelope who live on the Refuge, at the behest of conservation groups.40 While the beacons are intended to communicate a point of rescue, it is just as likely they signal the presence of Border Patrol and an increased chance of apprehension and deportation. (Fig. 5)

The blue lights of Rescue Beacons can be seen on the horizon from the Alamo Canyon Campground on the Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, Arizona. Bill Hatcher, Arizona, 2014. Courtesy of Bill Hatcher.

Conclusion

In this paper, I have put forward the interpretation of US Border Patrol rescue beacons as a tool of disappearance and obfuscation, despite their seemingly humanitarian design. I have elaborated on how the beacon’s effectiveness is not held to critical standards because of its position within the discourse of citizenship and as a tool for spatializing sovereignty. Freed from the burden of scrutiny, the beacons are active in Border Patrol’s effort to displace humanitarian intervention as the preferred method of aid. Existing outside of scrutiny, I have proposed the possibility that the beacons place undocumented migrants at a higher risk of further harm or death, either by deportation or by pushing migrants’ paths into even more remote and rugged terrain.

By situating the beacons as a product of a humanitarian border, they can be understood as playing an active role in “border-making” through their ability to be mobilized for securitizing and territorializing Arizona’s borderlands. They elastically demarcate space: they reach beyond the delineation of cartographic boundaries and federal land designations by the nature of their luminosity and ability to be easily relocated, creating a fluid border that adapts to changes in migrant routes and responds to the presence of nonstate actors. The beacons also bolster Border Patrol’s fabricated image as an altruistic agency while actively functioning to apprehend undocumented migrants who might otherwise be able to avoid detection.

The beacon is just one piece of Border Patrol’s ongoing process to rebrand itself as a humanitarian entity.41 In this reorganization of rights and responsibilities, Border Patrol is actively taking steps to portray humanitarian volunteers as smugglers, as evidenced in the 2019 criminal proceedings against No More Deaths volunteer Scott Warren. Such a move limits the capacity of humanitarian workers to operate in the borderlands while reorienting prevailing conceptions of immigration dynamics. The label of “security threat” that Border Patrol applies blindly to the undocumented is temporarily lifted, and these individuals are recast as vulnerable victims in need of rescue. Humanitarian workers are charged as deviant criminals, with acts such as providing life-saving water declared as federal offenses from aiding and abetting. Here, Border Patrol emerges as a humanitarian operation that equates its interests in border security as perfectly aligned with its newfound mission to preserve human life.42

Endnotes

1. Brittany Polliard and Ryan Ruegg, “Rescue Beacons (‘Panic Poles’),” National Border, National Park: A History of Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, https://organpipehistory.com/orpi-a-z/rescue-beacons-panic-poles/.↵

2. Lexico powered by Oxford, s.v. “beacon,” https://www.lexico.com/en/definition/beacon. ↵

3. John D Bullough, “Factors Influencing the Performance of Visual Distress Signals,” Journal of Search & Rescue 2, no. 1, (December 2017): 11. ↵

4. “#WaterNotWalls,” No More Deaths, http://forms.nomoredeaths.org/legal-defense-campaign/waternotwalls/.↵

5. Nicholas De Genova, “Spectacles of Migrant ‘Illegality’: The Scene of Exclusion, the Obscene of Inclusion,” Ethnic and Racial Studies 36, no. 7 (May 2013): 1190. ↵

6. For more on the consequences of Prevention Through Deterrence, see: Andreas, P. (1998), Cornelius, W.A. (2005), De León, J. (2015), Doty, R.L.(2011), Nevins, J. (2001), Rubio-Goldsmith et. al. (2006).

7. United States Border Patrol, “Border Patrol Strategic Plan: 1994 and Beyond” (July 1994), 12. ↵

8. Ibid. ↵

9. United States Government Accountability Office, “INS’ Southwest Border Strategy: Resource and Impact Issues Remain after Seven Years,” GAO-01-842, Washington DC, 2006.↵

10. Raquel Rubio-Goldsmith, Melissa McCormick, Daniel Martinez, and Inez Duarte, “The ‘Funnel Effect’ & Recovered Bodies of Unauthorized Migrants Processed by the Pima County Office of the Medical Examiner, 1990-2005,” Report, Binational Migration Institute, October 1, 2006.↵

11. “Desert Beacons Lead to Illegals,” Washington Times, March 14, 2007, https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2007/mar/14/20070314-110449-1170r/.↵

12. Nicholas De Genova, “Migrant ‘Illegality’ and Deportability in Everyday Life,” Annual Review of Anthropology 31, no. 1 (2002): 419-47. ↵

13. Yves Winter, “Violence and Visibility,” New Political Science 34, no. 2 (2012), 198. ↵

14. Jill M. Williams, “The Safety/Security Nexus and the Humanitarianisation of Border 354 Enforcement,” The Geographical Journal 182, no. 1 (March 2016): 34.↵

15. Didier Fassin, “Humanitarianism: A Nongovernmental Government” in Nongovernmental Politics, ed. Michel Feher with Gaëlle Krikorian and Yates McKee. (New York: Zone Books, 2007): 151.↵

16. Ibid.↵

17. Didier Fassin, Humanitarian Reason: A Moral History of the Present (Berkeley, California; London: University of California Press, 2012).↵

18. Williams, “The Safety/Security Nexus,” 27.↵

19. Fassin, Humanitarian Reason, 2012.↵

20. “Desert Beacons Lead to Illegals.”↵

21. United States Border Patrol, “Border Patrol Strategic Plan,” 6.↵

22. Marina Kaneti and Mariana Assis. “(Re)Branding the State: Humanitarian Border Control and the Moral Imperative of State Sovereignty,” Social Research 83, no. 2 (2016): 305.↵

23. Williams, “The Safety/Security Nexus,” 34.↵

24. Williams, “The Safety/Security Nexus,” 28.↵

25. William Walters, “Foucault and Frontiers: Notes on the Birth of the Humanitarian Border,” in Governmentality: Current Issues and Future Challenges, eds. Ulrich Bröckling, Susanne Krasmann, and Thomas Lemke (New York: Routledge, 2011), 138–164.↵

26. “Multiple Remains Recovered This Week,” No More Deaths/No Más Muertes, Press Release, May 8, 2019. http://forms.nomoredeaths.org/multiple-remains-recovered-this-week/.↵

27. Molly Hennessy-Fiske, “Should Activists Aid Migrants in the Desert, or Leave Their Fate to the Border Patrol?” Los Angeles Times, March 8, 2019, https://www.latimes.com/nation/la-na-arizona-migrant-rescue-trial-20190308-story.html.↵

28. Ibid.↵

29. US Fish and Wildlife Service, Environmental Action Statement for Categorical Exclusion, May 2018. https://www.fws.gov/uploadedFiles/EAS-CatEx_emergencyrescuebeacons.pdf.↵

30. Lisa Meierotto, “A Disciplined Space: The Co-evolution of Conservation and Militarization on the US-Mexico Border,” Anthropological Quarterly 87, no. 3 (2014): 652.↵

31. US Fish and Wildlife Service, Environmental Action Statement.↵

32. Walters, “Foucault And Frontiers,” 148.↵

33. US Fish and Wildlife Service, Environmental Action Statement.↵

34. No More Deaths Abuse Documentation Team, in conversation with the author, March 11, 2019.↵

35. Nicole Ludden, “Border Patrol, Aid Groups Differ over Desert Rescue Beacons,” Tucson Sentinel, May 20, 2019, http://www.tucsonsentinel.com/local/report/052019_rescue_beacons/border-patrol-aid-groups-differ-over-desert-rescue-beacons/.↵

36. Ibid.↵

37. From the forthcoming No More Deaths/No Más Muertes Disappeared Report. Translated from Spanish by No More Deaths/ No Más Muertes.↵

38. Author’s comparison of Recovered Human Remains data to geolocated beacons, as well as first-hand experiences of finding human remains while accompanying Los Armadillos on a search and rescue in proximity to two beacons, July 2019.↵

39. Samuel Norton Chambers, Geoffrey Alan Boyce, Sarah Launius & Alicia Dinsmore, “Mortality, Surveillance and the Tertiary ‘Funnel Effect’ on the U.S.-Mexico Border: A Geospatial Modeling of the Geography of Deterrence,” Journal of Borderlands Studies (2019), DOI: 10.1080/08865655.2019.1570861.↵

40. US Fish and Wildlife Service, Environmental Action Statement.↵

41. Kaneti and Assis, “(Re)Branding the State,” 318.↵

42. Curt Prendergast, “Prosecutor calls medical care ‘cover story’ for smuggling ring as Scott Warren trial wraps up,” Tucson.com, June 7, 2019, https://tucson.com/news/local/prosecutor-calls-medical-care-cover-story-for-smuggling-ring-as/article_5b5ef459-81a3-56fa-a6ed-4f7e1c908f6f.html.↵

Author Affiliations

Tara Plath is an independent researcher and recent graduate of Goldsmiths, University of London’s MA Research Architecture program.

DESIGN STUDIES BLOG

DESIGN STUDIES BLOG