It is only fitting that Gordon Parks’ famous photographic essay documenting the dire living conditions of the Fontenelles, an impoverished African-American family in late-1960s Harlem, is housed in a 7-month exhibition at The Studio Museum in Harlem, “the nexus for artists of African descent…and for work that has been inspired and influenced by black culture.”[1] The centennial of the iconic artist/activist’s birth offers an apt opportunity to highlight one of his most famous works, A Harlem Family, which was published in a March 1968 issue of LIFE magazine, for whom Parks was the first African-American staff photographer. Commissioned to capture “the source of America’s urban violence,”[2] Parks used his assignment as a means for alerting “thousands of readers across the country to the realities of poverty, racial discrimination, and economic marginalization.”[3] Rather than perpetuate the pathologies that plagued urban communities of color at the time, Parks embarked upon an ethno-photographic journey to portray a microcosm of American injustices that defined the late sixties and seventies. The photographic essay, alongside Parks’ written account, “The Cycle of Despair: The Negro and the City,” was well received by LIFE readers across the country, who, for the first time, bore witness to a reality they had never before related to or understood.

What Parks put forth was a seemingly simple narrative riddled with nuances. Aside from his liminal positioning as artist/photographer/photojournalist (a member of a relative elite) and activist/friend/advocate (of the Fontenelles and larger civil rights movements), Parks always acknowledged his work would never resolve America’s greatest social injustices. It was instead intended to illuminate, to a mass, unknowing American readership, issues like racism and poverty as they are manifested in the daily lives of individuals who are deeply entrenched within these systems of oppression. The aim was to encourage individuals to no longer isolate themselves from these issues but to instead feel a greater sense of connectedness, accountability, and humanity. This was certainly achieved—Parks’ essay immediately and unintentionally garnered an incredible amount of financial support for the Fontenelles, enough to buy them a new home in Queens and free them from their tenement in Harlem. However, in 1969, a few months later, the home was accidentally set ablaze, killing the father, Norman Fontenelle Sr., and one of his middle sons, nine-year-old Kenneth. Norman Sr. had been drinking that night to celebrate his newfound employment. He returned home, sat on the couch, lit a cigarette, and fell asleep.

This is only one of the many tragedies that followed—several members of the Fontenelle family died relatively premature deaths. However, none of these stories were included in the exhibition. In fact, it wasn’t until after I had finished viewing the exhibition that an engaging museum security guard informed me the supplementary books[4] just outside of the exhibition space contained essays that would completely transform my perspective—and, indeed, they did. I left the museum that evening deeply saddened by the story of the Fontenelles, more from the text I had read than the images I had seen. Not having known about Gordon Parks or A Harlem Family prior to viewing the exhibition, I was upset about and cognizant of the dangers of de-contextualization. However, what I had not realized at the time was that the absence of in-depth context within the physical exhibition space was perhaps deliberate and, in retrospect, incredibly powerful.

The delicate balance between content and context in museum exhibitions is one of the many intricacies of curatorial work that are not always initially apparent. A second viewing of the exhibition opened my eyes to the power of materiality and spatial design. Materiality, as co-creation between subjects and objects,[5] is constantly negotiated in museum settings, always relative to, but not completely dependent upon, the curator’s intention. Our ability to establish and reestablish relationships with objects and spaces is subject to the agency of material and immaterial things beyond us—something that can be exemplified through my change in perspective upon first viewing the exhibition and then reading the supplementary text shortly after. There was, again, a shift in perspective when I visited the exhibition several weeks later and was more sensitive to aspects beyond the photographs and written historical context. I had realized, this time around, that The Studio Museum, too, had engaged in this act of co-creation, carefully configuring Parks’ 47 photographs—many of which were not included in the original essay and were released for the first time—not necessarily to retell the Fontenelles’ story exactly as it had appeared in LIFE 45 years ago, but to explore within a contemporary social justice framework what truly made Parks a cultural icon: his artistry.

The exhibition is incredibly moving. Upon entering the gallery space, one takes note of the harmonious balance between the brown walls and framed black and white photographs. The overall dim lighting and mild spotlights on the images adds to the somber atmospheric quality of the exhibition space, a mood that is also reflected in most of Parks’ photographs. Perhaps the silence also justifies why such a prominent exhibition is situated in the basement of The Studio Museum. If you are lucky enough to view the exhibition when there is little traffic, you will notice the silence adds to the sensory effect. The absence of auditory distractions allows you to completely immerse yourself within the exhibition’s visual elements.

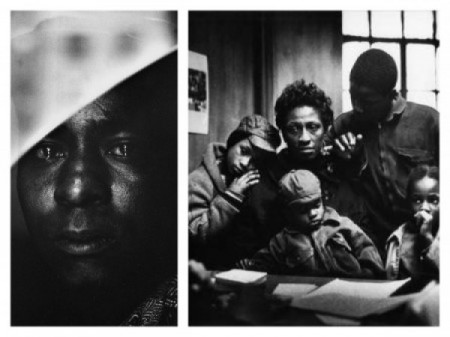

There is a natural inclination to begin towards the right, where the exhibition title and introduction stand out in white text. To the left of the text is the sole image The Fontenelles at the Poverty Board, which depicts a fatigued Bessie Fontenelle with her four youngest children closely surrounding her. It is both a strong image to isolate for its own merits and a perfect accompaniment to the adjacent introductory text. Following a counterclockwise movement, the next set of deliberately scattered images depict various spaces within the Fontenelle home, such as a window clouded by residue, a sink filled with rags and clothing to be laundered, a little girl’s clean dress hanging from a shelf amidst a mass of clutter, and the hands of a Fontenelle using masking tape to cover holes in a tattered wall. An adjacent wall also serves as a partition; it holds, on one side, an image of Norman Jr. reading in bed. Your eyes immediately fixate on the background, where there are large holes that have penetrated layers of dry wall, exposing the plaster and wooden slats of the home’s infrastructure. On the opposite side of the partition is a profile of Norman Fontenelle, Sr. The darkened exposure of the image highlights Norman Sr.’s watery eyes, looking directly into Parks’ camera. The image is absolutely stunning. I wondered why one of the most captivating photographs of the collection happened to be placed on the partition, rather than in a more prominent position on one of the central walls. My answer came a few images over.

The following photographs, arranged in a linear fashion, depict various members of the Fontenelle family, including the oldest Fontenelle son, Harry, whom the family had been visiting at a hospital (where Harry was recovering from a drug addiction). In one image, Bessie kisses Harry as he happily embraces her in his arms, whereas in the image directly before, Harry holds his head in his hand as if he were crying.[6] Similarly, in another image, Norman Sr. holds his youngest son, Little Richard, in his arms and between his legs as he laughs heartily. However, in the image that follows, he sits upright on a hospital bed with a scalded face that exuded pain, injured from the night his wife burned him with a pot of boiling liquid in retaliation for his incessant physical abuse. The strong juxtaposition of each pair of images signifies the Fontenelles’ fluctuating emotional states and the fragility of their family dynamics. Indeed, Parks’ photographs collectively capture a cycle of despair, one that is reinforced by the photographs’ spatial configuration—a feature attributed to exhibition design.

Standing directly in front of these photographs, I turned to the right and unexpectedly experienced the most heart-wrenching moment of my viewing experience. The first image of the exhibition, depicting Bessie and her youngest children at the Poverty Board, is foregrounded by the profile of a teary-eyed Norman Sr. (the photograph that is fixed onto the partition). The distant pairing of these two images is absolutely chilling—the angling at which the two photographs speak to each other, where Norman Sr.’s gaze meets that of his family’s, communicates (through both visual and spatial representation) a deeply shared and distancing sadness. It was as if Gordon Parks had foreshadowed the family’s fate. Norman Sr.’s profile is not misplaced at all. In fact, it is perfectly situated within the exhibition, allowing you to glance back, from almost any photograph beyond the partition, to find his direct gaze. This image served as a constant reminder that Parks’ photographs were not merely intended to relay messages of social injustice. More importantly, they served as a powerful family narrative. By exposing the humanity of his subjects, Parks demonstrated that an impoverished family in Harlem was still, at its very core, a family like any other. His technique is a means to social justice.

Reaching the end of the gallery space, one notices the famous image of the youngest Fontenelle daughter crying, the very same image that made the cover of LIFE magazine in March 1968. The very fact that this is exhibited last, prior to reaching the exit, reminds me this exhibition is not only about the Fontenelles—it is about the Fontenelles, as depicted through Gordon Parks’ artistic talent and creative genius. Close to the introductory text, positioned less prominently on a separate wall to the right, is an image of Gordon Parks surrounded by the Fontenelle children. From the very beginning of the exhibition, The Studio Museum subtly communicates that the feelings and experiences we have through this powerful collection of images can be attributed to the man behind the camera. This reminds us that photographs are never objective, but instead the time-bound products of subjective experiences. How we see the Fontenelles is how Parks saw the Fontenelles, and although we will never feel exactly what Parks felt, these images bring us closer to his immersive experience in the Fontenelle home.

What The Studio Museum in Harlem has achieved through this exhibition is exactly what it delineates in its mission. In the exhibition’s introductory text, Director and Chief Curator Thelma Golden writes:

“In 1968, the same year Parks’ photo essay was published in [LIFE] magazine, The Studio Museum was founded a few blocks from where the Fontenelles lived. This was no coincidence: the Museum came to Harlem under the premise that, as the founding documents state, “the arts can help restore our cities and the people who live in them to a sense of dignity and to a wider comprehension of human needs.”

Forty-five years later, The Studio Museum continues its tradition of opening up space to not only relay the otherwise untold stories of communities of African descent, but to also celebrate the works, lives, and legacies of artists like Gordon Parks. As a venue reserved for arts within and about black culture, The Studio Museum maintains Parks’ pursuit of social justice, only now within a contemporary arts-oriented framework. In many ways, Parks’ dreams of social justice have been realized through the museum’s strong presence in the Harlem community and beyond. What we witness through Gordon Parks: A Harlem Family 1967 is the poetic intertwining of social and spatial justice.

[1] “About,” The Studio Museum in Harlem, http://www.studiomuseum.org/about/about (accessed February 24, 2013).

[2] Thelma Golden, Elizabeth Gwinn, and Lauren Haynes, eds., Gordon Parks: A Harlem Family 1967 (New York: Steidl/The Gordon Parks Foundation/The Studio Museum in Harlem, 2013), 11.

[3] Wall text, Gordon Parks: A Harlem Family 1967, The Studio Museum in Harlem, New York, NY.

[4] Gordon Parks: A Harlem Family 1967 (2013), the official exhibition book with the full LIFE essay included, and Gordon Parks’ Half Past Autumn: A Retrospective (1998).

[5] Janet Borgerson and Jonathan Schroeder, “Materiality and Identity” (presented at Aftertaste 2013: The Atmosphere of Objects, the biennial symposium of Parsons The New School for Design, MFA Interior Design, School of Constructed Environments, New York, NY, February 22-23, 2013).

[6] In his written essay, “The Cycle of Despair: The Negro and the City,” Parks describes this difficult moment when Harry confessed to his mother his uncertainty around being able to stay away from drugs. Seeing how much his confession had hurt his mother had, indeed, brought Harry to tears.