Walking into Amy Hill’s “Age of Delightenment” is like setting foot in a place both familiar and strange; it’s stepping into a favorite coffee shop only to step out in a different country, or sitting on a couch with good friends and settling into the evening’s conversations only to witness everyone speaking a different language. Hill’s paintings confront their audience with both a haunting familiarity and anachronistically foreign stare in such a way that you can’t help but look back into the eyes of one of Hill’s perfectly rendered 15th century portraiture models and say, “Who, me?” You look around in the off chance that the glance was intended for another and find everyone else asking themselves the same question and looking around for clarification. It’s not easy to be confronted by a painting and it’s easy to skirt the gaze and let the person behind you assume the responsibilities instead.

Hill reappropriates classic 15th century style Flemish portraiture by pairing the signature stoicism of subjects of Early Netherlandish altarpieces and portraits with contemporary backdrops exploding with ripe controversy and questions. Part of what’s so significant about Hill’s work is that rather than serving as pure tension, the juxtaposition of a 15th century face with a contemporary world surrounding her actually brings new context to the historical ‘foreground.’ History is on our side with Hill, and rather than creating a dichotomy or tug-of-war just for art’s sake, the tension culminates in a palpable reveal of contemporary attitudes made possible only by and through this historical lens.

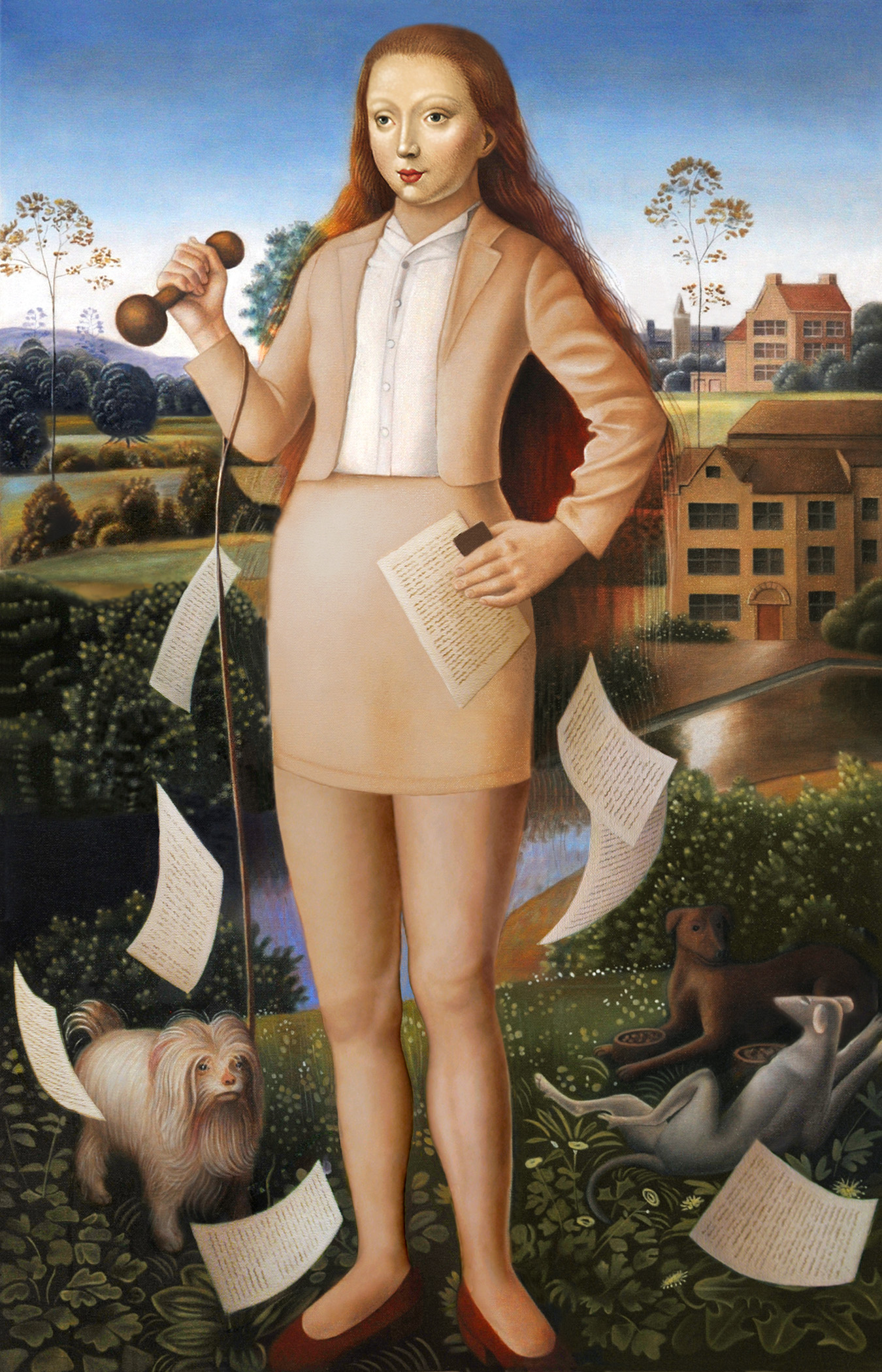

Jan van Eyck’s Ghent Altarpiece, arguably the most well recognized piece to come out of the Early Netherlandish period Hill draws from, sought a new conception of art in which the idealization emphasized by earlier medieval tradition yields to more natural or perhaps unidealized conceptions of subjects.[1] Significant about the panel is that it gives two very distinct perspectives depending on whether it is open or closed. In a similar vein, Hill’s reworking of the seven deadly sins vis-à-vis contemporary ‘sins’ (Syntheticity, Apathy, Workaholism, Deprivation, Distraction, Nymphomania, and Paranoia) reveals the unromantic realities of our contemporary attitude. We do not want to think we resemble the subject in Hill’s Apathy painting, yet, the 15th century portraiture model who has been sitting for hours undoubtedly has our very own recognizably jaded, dispassionate expressions. Or, rather, we have hers.

Hill plays with the thinking of the Enlightenment, when the idea of challenging traditions grounded in faith by replacing them with reason was a noble cause that hadn’t yet gone too far. But the portraits ask, have we left these traditions too far behind? The relationship between the loss of religion/faith and a preoccupation with the self seems almost causal, as the sacred is left behind in lieu of the pursuit of self-interest and individual aims. In perhaps her most provocative of the Seven Deadly Sins collection, aptly entitled Apathy, the female subject looks at her freshly painted nails while firefighters work to salvage a burning house. A plane looms from a building, half jutted out as if it had just been trying to crawl through before getting stuck there. Throughout the Sins collection the same perfectly dispassionate face emerges; always in the foreground, apathetic or unsympathetic to a background that would necessitate a jumping out of the self and back into a care of, or faith in, other people in order to merge with.

Hill plays with the thinking of the Enlightenment, when the idea of challenging traditions grounded in faith by replacing them with reason was a noble cause that hadn’t yet gone too far. But the portraits ask, have we left these traditions too far behind? The relationship between the loss of religion/faith and a preoccupation with the self seems almost causal, as the sacred is left behind in lieu of the pursuit of self-interest and individual aims. In perhaps her most provocative of the Seven Deadly Sins collection, aptly entitled Apathy, the female subject looks at her freshly painted nails while firefighters work to salvage a burning house. A plane looms from a building, half jutted out as if it had just been trying to crawl through before getting stuck there. Throughout the Sins collection the same perfectly dispassionate face emerges; always in the foreground, apathetic or unsympathetic to a background that would necessitate a jumping out of the self and back into a care of, or faith in, other people in order to merge with.

Art traditions are inherently bound up in their historical contexts, and it is only by understanding the weaving between the two that we can understand how to appropriately reappropriate: how to utilize the artworks in our contemporary context to illuminate the truth through tension. But anachronism isn’t really anachronistic when something jumps out of its historical context and into another one. Hill’s work is poetic and apt, to say nothing of the meticulous perfection of her detail. The reworking of the sins is just one part of her collection, the breadth of which continues to push the limits of historical portraiture. Seeing such an overtly obvious contrast between styles or time periods in a single work initiates a kneejerk reaction: juxtaposition. But Hill does more than merely show contrast; she engages the two time periods in such a way that they reveal each other’s secrets.

In addition to Seven Deadly Sins, pieces from Hill’s Bohemians and Tribute to Arcimboldo collections are also on view at The Front Room Gallery located at 147 Roebling Street in Williamsburg, Brooklyn through October 13th. Gallery hours are Friday-Sunday 1-6PM and by appointment.

-Amie Zimmer

Images: “Workaholism” & “Apathy” by Amy Hill, Courtesy of Front Room Gallery

[1] Ainsworth, Maryan W. “Early Netherlandish Painting”. In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/enet/hd_enet.htm (March 2009)